It’s a curious coincidence that the kinetic sculptor Takis passed away this summer, just weeks after a new generation of artists’ protests successfully forced the resignation of Whitney Museum of American Art Board Vice-Chairman Warren Kanders. It was, after all, Takis’s puerile gesture in 1969 of removing his artwork from an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art that sparked the formation of New York’s Art Workers Coalition. In a flurry of activity in 1969 and 70 the group took on museum accessibility, racial representation, the Vietnam War, and workers’ struggles.

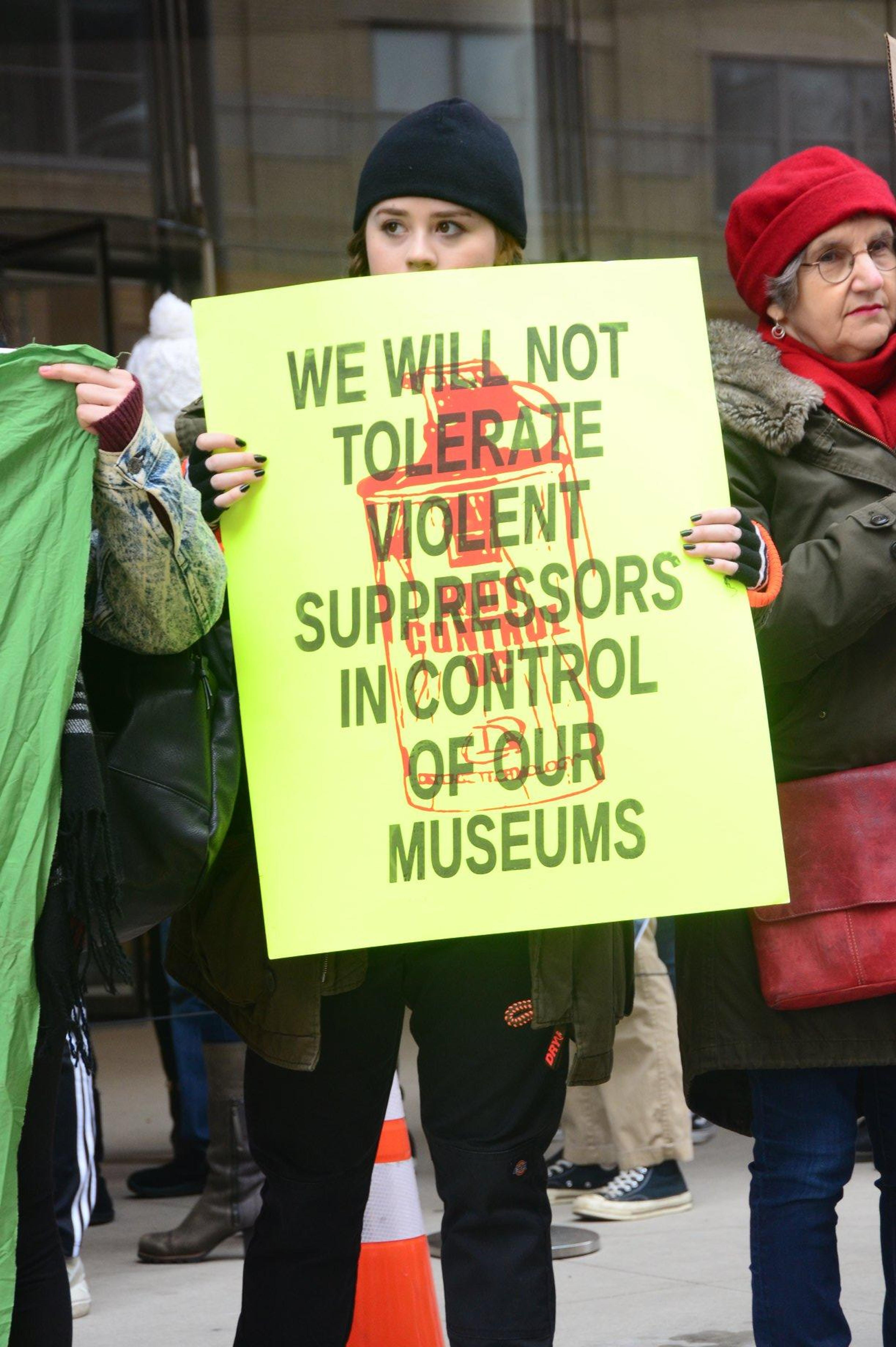

Fifty years after the AWC, we have Decolonize This Place. Founded in 2016 to protest “This Place,” a show at the Brooklyn Museum of photography from the occupied West Bank, DTP exploded a rather straightforward claim – that “This Place” was too sympathetic to Israeli colonisers and should be decolonised – into a postmodern popular front, claiming issues ranging from colonialism, indigenous land rights, black struggles, gentrification, and more. The Whitney fell into their crosshairs when Hyperallergic broke the story that Kanders owns Safariland, a company that produces tear gas used at the US-Mexico border. Over one hundred Whitney staff members published an open letter demanding that the Museum consider asking for Kanders’s resignation. DTP organised several protests demanding his expulsion leading up to the Biennial, a recurring exhibition that sets the watermark for American art. Its prominence has made nearly every iteration subject to some kind of scandal, but this time the scandal thoroughly eclipsed the show itself.

Decolonize This Place

DTP can’t take all the credit for Kanders’ departure, though. The Biennial had been running for several weeks before prominent black critics Hannah Black, Ciarán Finlayson, and Tobey Hassett published “The Teargas Biennial” in Artforum, prompting eight artists to ask that their work be removed from the exhibition. After months of holding out against ongoing protests, it took Kanders only a few days after that episode to announce his resignation. It happened so quickly that none of the artworks were actually removed. The show remains intact for the remainder of its run.

One walks away feeling that something extraordinary has happened and at the same time nothing at all. Critic Ben Davis was quick to hail it as a paradigm shifting event; DTP vowed to make it a starting point for a larger movement to decolonise museums. But the earth has not yet shattered, and I highly doubt it will.

If this signals any kind of change, it’s but another step on a long, steady march: the subordination of art – you know, that stuff you look at – to the politics that surround it, so much so that all those pictures become a footnote to the struggle .

I do agree with Davis on one point: Kanders’s resignation will be what the 2019 Biennial is remembered for. But that’s precisely the problem: it will be the sideshow, not the art, that goes down in history.

Installation view of the Whitney Biennial 2019 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, May 17-September 22, 2019). Photograph by Ron Amstutz

This Biennial was modest, yes, but excellent, and not only because it’s the youngest and most diverse Biennial in recent memory. Foregoing the swagger of the 2017 iteration, this Biennial lets the artworks shine. The curation wisely shifts from a focus on identity as subject matter to identity as characteristic. A universalising view of blackness gives way to a diversity of black artists, for example. Aesthetic accomplishments are uplifted and given room to breathe. The Whitney seems to have resolved (as much as possible) the issue of identity by reframing it as but one trait shared – or not – by unique artists.

Nonetheless, identity did become an issue after the first round of reviews. The claim by (mostly white, mostly male) critics that the show wasn’t radical provoked immediate backlash. “White supremacy doesn’t get to decide whether our work or actions are ‘radical’ enough to liberate our peoples from white supremacy,” DTP warned . Participating artist Simone Leigh opined in an Instagram post that the mostly-white reviewers didn’t get her work because it was intended “for black women.” But her statement was immediately followed by a list of prerequisites for comprehension that would take a master's degree to attain, a gesture Hyperallergic’s Seph Rodney clocked as “another kind of gate keeping.” His warning bears repeating:

“The danger here is that Leigh might cordon off her work from general critical assessment by in essence claiming that it exceeds the grasp of those who haven’t read the canons she’s read. And thus Leigh or other artists might take up the position that any critique that issues from outside their province of knowledge is invalid. ...I wonder how many Black women would be conversant with the topics she’s mentioned, and of what class and upbringing? While these critics may be mistaken or only partially correct, Leigh’s statement ventures toward trying to make art that is critically bulletproof. It shouldn’t be.”

This opposition to criticism seems a common thread around this Biennial, not only in these arguments about who has the right to critique whom but also as a symptom of the Kanders scandal and the politics of removal that it thrived on. Increasingly, one gets the sense that, at least in public discourse, the 2019 Whitney Biennial of American Art is not really about art .

Simone Leigh, Stick , 2019

The identity debates were reignited when Elizabeth Méndez Berry and Chi-hui Yang made a trenchant call in the New York Times for more diversity in criticism. They wrote that “old-school white critics ought to step aside and make room for the emerging and the fully emerged writers of color.” They’re right. In diversity, art criticism lags even behind our object of critique. It’s an industry run on nepotism that is difficult for outsiders to breach. But step aside may not have been the best choice of words. It was quickly picked up in a full-blown temper-tantrum from self-professed old school white male critic, Kurt McVey . As wrong-headed as McVey’s response was, Berry and Yang’s proposal remains an impoverished way forward.

Step aside. Step down. Resign. Withdraw. Decolonise. Undo. These are the slogans so-called progressives have thrown at the Whitney. They reveal a profoundly limited political imagination in which better worlds can only be conceived as acts of erasure, the undoing of harms. Despite atrociously low pay (as the world saw in the publication of a riveting Google Sheet detailing art workers’ pay), Whitney employees organised to demand not higher wages but Kanders’s ousting.

Museums are both liberating and oppressive: institutions of freedom and institutions of control.

Politically, Kanders’s departure accomplishes nothing; perhaps less. His company will continue to manufacture tear gas, and governments will continue to use it. The gesture isn’t so much about punishing Kanders but of washing our hands of him to propagate the myth of the art world’s own purity. In that way the gesture is profoundly dangerous: the myth of purity couldn’t be further from the truth.

Unlike Europe’s largely publicly funded institutions, museums in the United States are almost entirely privately funded. DTP sees Kanders as an example of “toxic philanthropy” which “cannot be normalized.” But the distinction between toxic and benign philanthropy remains unclear. After all, even the most inoffensive corporation makes its fortunes through the exploitation of labour.

Installation view of the Whitney Biennial 2019 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, May 17-September 22, 2019). Photograph by Ron Amstutz

If any progress can be made as we move on from this shitshow, it would be in the recognition that museums are complicated, thoroughly entangled in our political, capitalist world. It’s a truth that doesn’t lend itself to sloganeering or fun protests (“We had a party here for nine weeks” one DTP member remarked ). Museums are both liberating and oppressive: institutions of freedom and institutions of control. It would also require an acknowledgment that on the scale of politics, the makeup of a museum board means little. Do immigrants fighting through tear gas at the US-Mexico border have an interest in whether or not the man profiting from it sits on a museum board? No.

Adorno’s comment on pseudo-activity comes to mind regarding “praxis that takes itself more seriously and insulates itself more diligently from theory and knowledge the more it loses contact with its object and a sense of proportion.” One gets the sense that both the object (art) and sense of proportion (rather small) have been utterly forgotten as Leigh, DTP, and others attempt to absolutely insulate themselves from any criticism – DTP even going so far as to pre-emptively damn anyone who might try.

Art might still have a role to play today. The corpse is still twitching. But that can only happen if all of us arts workers do our jobs with rigor and fearlessness: make art, show art, critique art. That and nothing less.

Whitney Biennial 2019

17 May – 22 September 2019

https://whitney.org/exhibitions/2019-Biennial

Allison Hewitt Ward is a Brooklyn-based critic. Her work investigates the intersections between art and politics. She teaches at the MFA Art Practice department of the School of Visual Arts in New York.