The exhibition’s title sounds like a catchy argument in current discussions on cultural appropriation, offering hybridity as a guiding principle. But the group show at mumok is more than just another reflection on collective authorship or the migration of forms. The participating artists were invited to enter into dialogue with works of their choosing from the museum’s collection and recontextualize or even appropriate them. One can feel the curators’ ambition to open mumok up to postcolonial histories and queer perspectives, albeit in a way that does not challenge an institution’s identity significantly. That said, several of the exhibition’s seven participants address topics that have long been on the Western museum agenda and have slowly been seeping into these institutions’ practices.

The display system designed by Anetta Mona Chişa and Lucia Tkáčová offers a good starting point in its eco-friendly transformation of the architecture leftover from the museum’s previous exhibition. Plasterboard walls have been cut open to offer a rough but elegant clash of material and spatial configurations, separating the works into sections while offering space for them to converse. Slavs and Tatars’ musing on translation, transliteration, and the Polish word for anus, OdByt (2015), is a bit lame, but as a kind of Tree of Knowledge, Nilbar Güreş’s Mayzu (2022) is a colorful, queer fantasy that invites participation, introducing bisexual bonobos to Lois Weinberger’s photographs of resilient, off-road vegetations, questioning boundaries of all kinds.

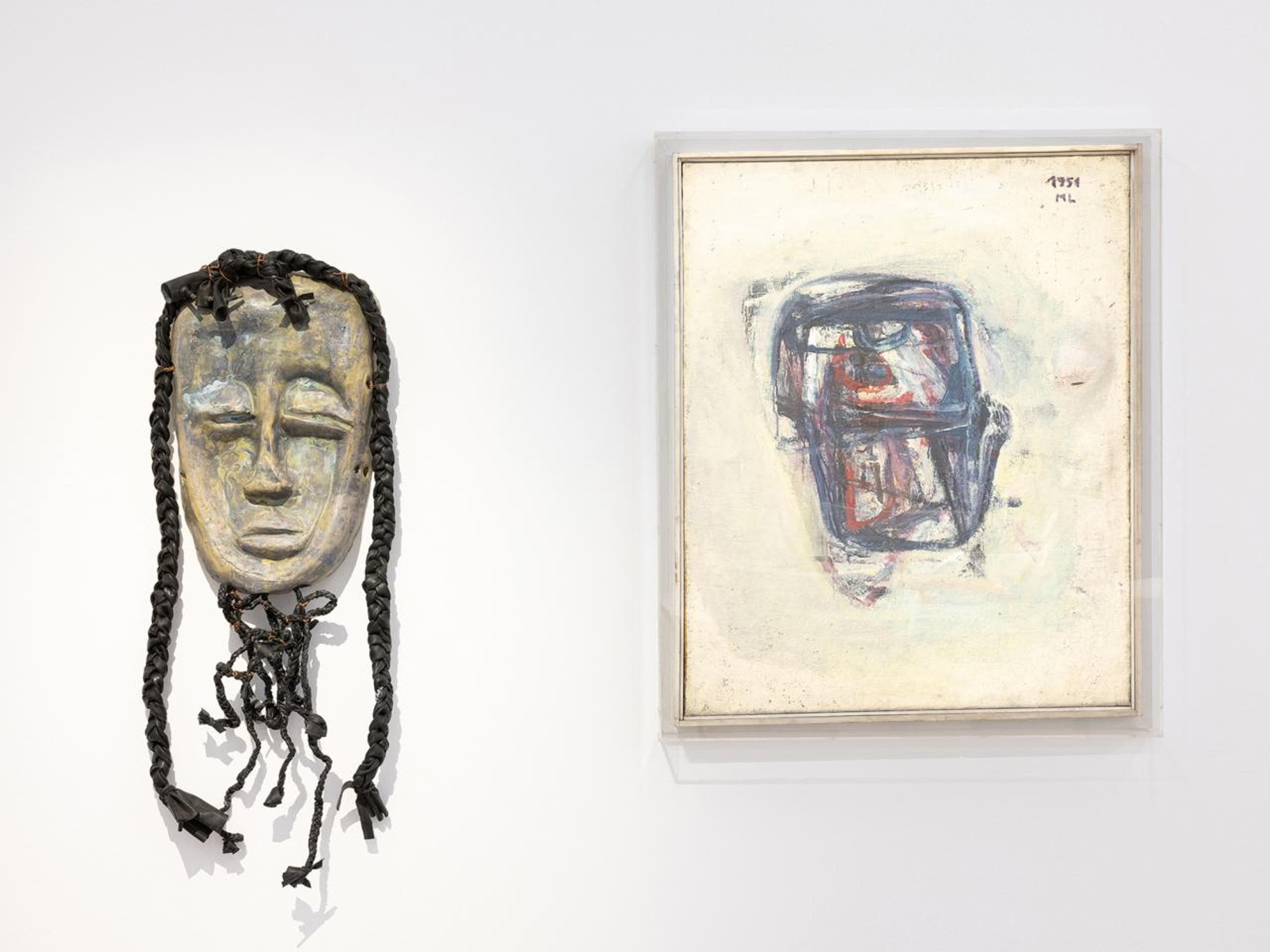

Left: Leilah Babirye, ohne Titel, 2022; right: Maria Lassnig, Informel, 1951. Installation view, mumok, Vienna, 2022

Mariana Castillo Deball’s video El dónde estoy va desapareciendo (The where I am is vanishing; 2011) tells the story of the Codex Borgia, a pictorial manuscript from 16th-century Central Mexico that was raided by Spanish colonialists, sold in Europe, and almost destroyed, before ending up in the Vatican Library in 1902. In the paper work Microhistoria (Microhistory; 2011), Deball adopts the fanfold structure and the drawings of the Codex to rewrite its tales of ancient gods and mantic images, turning the holy book into one of her “Uncomfortable Objects,” which force us to view the world from their perspectives. The blue, red, and yellow papier-mâché sculptures that inhabit the metal framework of the display like endemic organisms are printed with photographs the artist made during a long stay in Brazil. Deball has mingled her installation with several untitled works by Louis Goodman, small-format assemblages of everyday objects that look like encounters with alien realities.

These sculptures, which resemble mundane relics or surrealist moodboards, bridge Deball’s show-within-the-show with the photo collages and sculptures of Nicolás Lamas. He works in a similar manner, combining and arranging found and self-made objects by looking for similarities or complements. Among the objects he has selected from the Natural History Museum Vienna are bones, taxidermies, animal skulls, display cases, and storage units. Fossilized plants inhabit sneakers and dice rest in a bird’s nest, while medical prosthesis and animal bones amalgamate in plastic cases. Lamas realigns what science separates and creates new entanglements between organic bodies and technologies. Objects lose their scientific markings and become illustrations of the Surrealist doctrine of objective chance and Donna Haraway’s thinking beyond categorization.

Mariana Castillo Deball, Uncomfortable Objects, 2012. Installation view, mumok, Vienna, 2022

Leilah Babirye’s artistic practice, meanwhile, takes a different approach that effectively questions the very identity of the European museum. Her bust-like figures, sculpted of wood, ceramic, or metal and affixed with found everyday objects, are made to echo a prevailing Western view of traditional African cult objects, which were often raided from the communities that produced them and entered into museum collections as “exotic” or “archaic” masterpieces. Placing her sculptures next to iconic works by Constantin Brâncuși, Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, the Ugandan artist creates a harmonious ensemble of heads, where lustrous, painterly glazes shimmer alongside bronze and brass.

Babirye’s works also reflect elements of the Ugandan social order relevant to gender and sexuality. In Buganda, a Bantu kingdom that makes up the largest of present-day Uganda’s four regions and includes the artist’s birthplace, the capital Kampala, clan members historically viewed themselves as siblings without regard to their birth relationships and were often named after plant or animal totems. Babirye intervenes in these traditions in the titles of her sculptures by adding the word kuchu – a Lugandan word predominantly used for self-identification as queer – to patrilineal nomenclatures, as in Nakawaddwa from the Kuchu Ngabi (Antelope) Clan (2021). This reclaiming creates a new kind of community for an artist who sought asylum in the United States in 2018, after she was publicly outed as a lesbian in a country where same-sex relationships and non-conforming sexual orientations are violently stigmatized.

Nilbar Güreş, Mayzu, 2022. Installation view, mumok, Vienna, 2022

Babirye likewise appended “kuchu” to each of the European pieces she selected from mumok’s collection, creating “a queer army of lovers” from works evidently influenced by non-European art: Giacometti’s Buste de Diego (Bust of Diego; 1955) is now a member of the Kuchu Royal Family of Buganda, as is Constantin Brâncuși’s La Négresse blonde II (Blond Negress II; 1933) – a relief given the latter sculpture’s racist title. The new configuration queers the given and shows the Western appropriation central to artistic modernism for what it has always so blatantly been: an exploitation and theft of works and forms by a dominant capitalist culture. Even in its status as a temporary exhibition, “mixed up” demonstrates how effective that simple act of showing can be.

Anetta Mona Chişa and Lucia Tkáčová, Nothing Nowhere into Something Somewhere, 2015/2022, book pages

___

“mixed up with others before we even begin”

mumok

26 Nov 2022 – 10 April 2023