A large neon light bearing the sign “Glück auf!” twinkles prominently atop a high-rise in the center of Oberhausen. It was a greeting of good luck among miners – once the largest demographic in the Ruhr town – to emerge unscathed from their explorations into the underbelly of the earth. In the speleological quest of the Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen, which wrapped its 69th edition this spring, to search for (short film) gems means diving into dark cinemas. Thematic series and tributes to artists and curators from the Kurzfilmtage’s history feed into a sort of ongoing self-retrospective that make the festival a true goldmine – a treasure enjoyed since its foundation in 1954, when it became the world’s first short film festival. While today we understand the short format to mean experimental and moving-image artworks, the festival is also home to children’s films, music videos, and expanded cinema. A strange yet welcoming grotto, where those eluding straightforward affiliations with the art world or art-house cinema may find refuge.

It was a mixed bunch in the German and International competition strands, with veterans such as Laure Prouvost (*1978) and Colectivo Los Ingravídos (*2012), as well as newcomers like Kyrgyz filmmaker Alizhan Nasirov (*1980) or Indonesian interdisciplinary artist Taufiqurrahman Kifu (*1994), among the prizewinners. Oleksiy Radynski’s (*1984) Chornobyl 22 (Ukraine, 2023), awarded the main prize for its somber account of the nuclear power plant’s occupation by the Russian army in 2022, reflected this year’s preference for non-fiction, which characterized the strongest titles on view. Perhaps due to their confrontations with reality – whether it was an intimate one, as in I think of silence when I think of you (Sweden, 2022) by Jonelle Twum (*1992), or explicitly political, as in Gretel Marín Palacio’s (*1989) Camino de lava (Cuba, 2022) – many of the awardees featured an undercurrent of melancholy, a longing to own and transcend the worlds represented onscreen.

Still from Laure Prouvost, Every Sunday, Grandma, Belgium, France, 2022. © Laure Prouvost

In particular, two titles presented in the International competition and a third in the German competition embodied a pensive and introverted spirit, employing literature and theory as both “muses” and work tools. In Untitled (UK, 2022), Sweatmother created a highly performative work through technical synthesis. The artist is seen facing two monitors and a mixer, through which he controls the movements of a female figure appearing on both screens, a feminine, hybrid version of himself, neither entirely digital nor analog. Was she “engineered as ‘she,’ programmed with human cis-het language to fulfill” his desire? she asks. A dialogue between the two ensues, borrowing from Paul B. Preciado’s Can the Monster Speak? (2021), Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (1855), and Sweatmother’s own thoughts on trans identity before the support of medical technology became available – “to be up and straight, without comfort.” It is also tempting to see the film as a split-screen experiment, but classic film language fails to properly describe Untitled . Touching, true – in conversation and transmission only, it seems, can its experience be shared.

Defying categorizations is also a central to the emblematically titled Nameless Syndrome (South Korea, 2022) by Jeamin Cha (*1986). In a muffled atmosphere, scenes of female patients undergoing medical treatment (hearing tests, mammograms, Watsu therapy) visually backdrop an essay about illness, language, and and how we yield what we know in scientific as well as personal contexts. Mixing the artist’s thoughts with texts by Susan Sontag, Anne Boyer, and Carlo Ginzburg, an unidentified, off-camera voice attempts a diagnosis whose focus is not a disease, but the arbitrary and imperfect means used to render diagnoses. Citing psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk, Cha states: “Like the relationship between geography and history, body and mind are connected.”

Still from Gretel Marin Palacio, Camino de lava, Cuba, 2022. Principal Prize. © Gretel Marin Palacio

And so are images and language: In Gernot Wieland’s Turtleneck Phantasies (Germany, 2022), textual elements are key in providing visual and conceptual framework for the dis-composed self. As in his previous Bird in Italian is Uccello (2021), Wieland’s (*1968) memories of growing up in rural Austria and the obscure biographies of outsider figures inspire eccentric parables illustrated by drawings, home videos, and original footage, all shot on 8mm film. Whether spoken or written, resembling a therapy session, a philosophical inquiry, or a conceptual graph, textual material dominates the screen. It even morphs into symbolic objects: Books, letters with handwritten poetry, maps, and decal tattoos offer the artist old obsessions and stories to retell. Joining Austrian writers Elfriede Jelinek and Thomas Bernhard in openly despising his homeland – “a country of hidden structures of fear” – Wieland is also fascinated with mental disorder as a means of artistic creation, but also as the result of imposed societal structures. . Relief may come with the erasure of any system, including the form essential to this film. The camera turns up to the monochromatic blue of the sky, exemplifying the artist’s only possible action to live in harmony with a world “where coincidence seem to rule”: to become invisible even to one own’s gaze.

Gernot Wieland, Turtleneck Phantasies, Germany, 2022. Prize of the German Competition. © Gernot Wieland

And what about machines – do they see themselves? This is one of the many questions raised in the thematic section “Against Gravity,” entirely dedicated to screen-captured, animated films based on real-time video games or game engines (also known as machinimas), dating back as far as Phil Solomon’s (1954–2019) experiments in the late 1980s. In Adam Killer (US, 1999), Brody Condon’s (*1974) point-and-shoot perspective attacks multiple 3D models (possibly of Condon himself) that leave streaks of visual glitches alongside the blood trails: In a fleshy and camouflage-like palette, a painting thick with layers – not unlike John Smith’s Dad’s Stick (2012) – takes shape. In Descent Into Hell (Netherlands, US, 2022), Jacky Connolly (*1990) replaces the fake props disseminated around Grand Theft Auto V’s fictional city of Los Santos with their original Los Angeles counterparts. A 7/11, an Esso gas station, the city’s legendary Hotel Cecil: stepping stones along the film’s journey across video-game California. Wildfires/sunsets glow orange as jazzy tunes are heard in the background and Connelly’s enigmatic texts are occasionally read in voice-over, creating the first “melo-machinima.” Truth is, an excess of technology oozes humanity, instead of removing it from the equation. And we develop affect for the machine, because worlds in machinimas are closer than they appear. Utterly inefficient, riddled with flaws, and populated by characters hostage to their own finiteness: Doesn’t that sound familiar? If, in the words of theorists Luciana Parisi and Tiziana Terranova, digital images throb with the “desire to take over the real,” artistic authorship might not simply surrender and join that mimesis.

Still from Brody Condon, Adam Killer, US, 1999. © Brody Condon

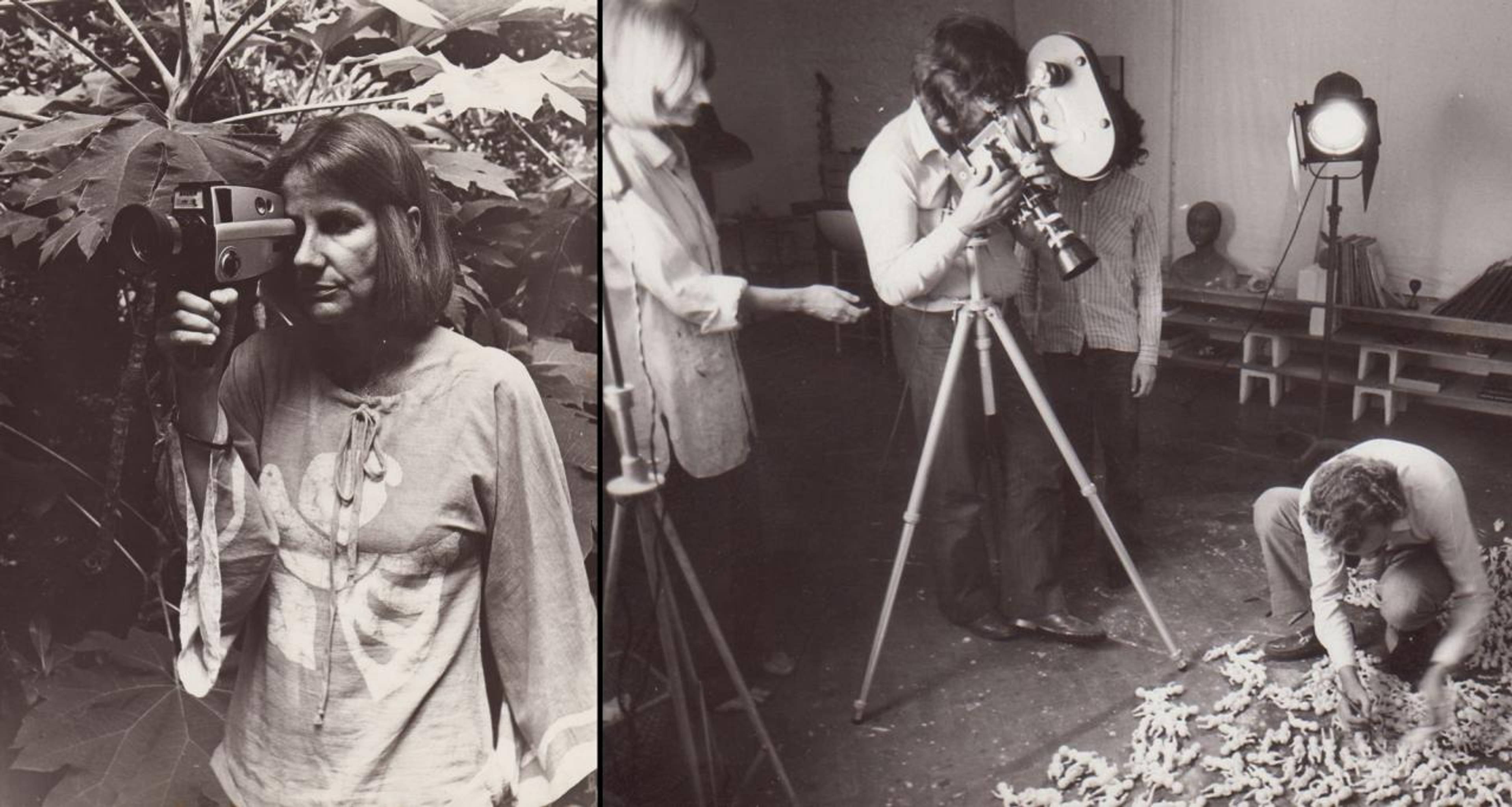

Next to the machinimas’ (somewhat alienating) takeover of the festival, it was a delight to encounter the in-progress archiving of Narcisa Hirsch (*1928) and Marie Louise Alemann (1927–2015) at Kurzfilmtage, whose collection sometimes holds the only existing copy of certain titles. Both German-born, with intriguing biographies that could have been penned by Nathalie Lèger or W.G. Sebald, they were central to the experimental Super 8 scene in Buenos Aires in the 1970s. In Hirsch’s La Noche Bengalì (1980), inspired by Marguerite Duras’s India Song (1975), spatial coordinates and gendered positions are teased, as a female character is seen gently stepping over her male counterpart. Alemann’s Legítima Defensa (1980) shows the artist herself disguised as a freakish, white creature wielding a weapon-like object and staring back at the camera. To sustain a persistent gaze – be it the artist’s, the viewer’s, or the (film) machinery’s: Is that an act of self-defense, or the ultimate seduction?

Between retrospective and future visions, old and younger discoveries, the viewer may forget that the primary purpose of films is to record their own present. This, the Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen knows very well, as it continues to stimulate friction and induce overlaps between different times and views. Regardless of their age or their borrowing from other media, many of the films on view acknowledged and cherished the tension between their outlook and ours. Perhaps that’s what it was, that melancholic soul that inhabited these works and played out before our eyes – no less than an acute form of filmic self-awareness.

Jacky Conolly, Descent Into Hell, Netherlands, US, 2022, © Jacky Conolly

Left: Narcisa Hirsch, Marabunta, film, 1967; right: Narcisa Hirsch and team during the production of Pink Freud, c. 1973. Courtesy: the artist

___