1.

Hong Kong, a Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China, lives in an area of my mind with high green hills and banquet halls and concrete residential towers whose balconies jut like vertebrae along spines made of stone. Wild boar roam the hills in the dark. Political prisoners in the Stanley jail bake in humidity and sweat without any air-conditioning. Jet-lagged from New York, I was taking a nap one afternoon in our hotel on the southern coast of Hong Kong Island, and was dreaming that someone I loved was handing me a piece of paper. I began pulling at it with both hands – it was blank, no message – until I felt someone kissing my face.

“Wake up, we’re going to be late,” Drew said.

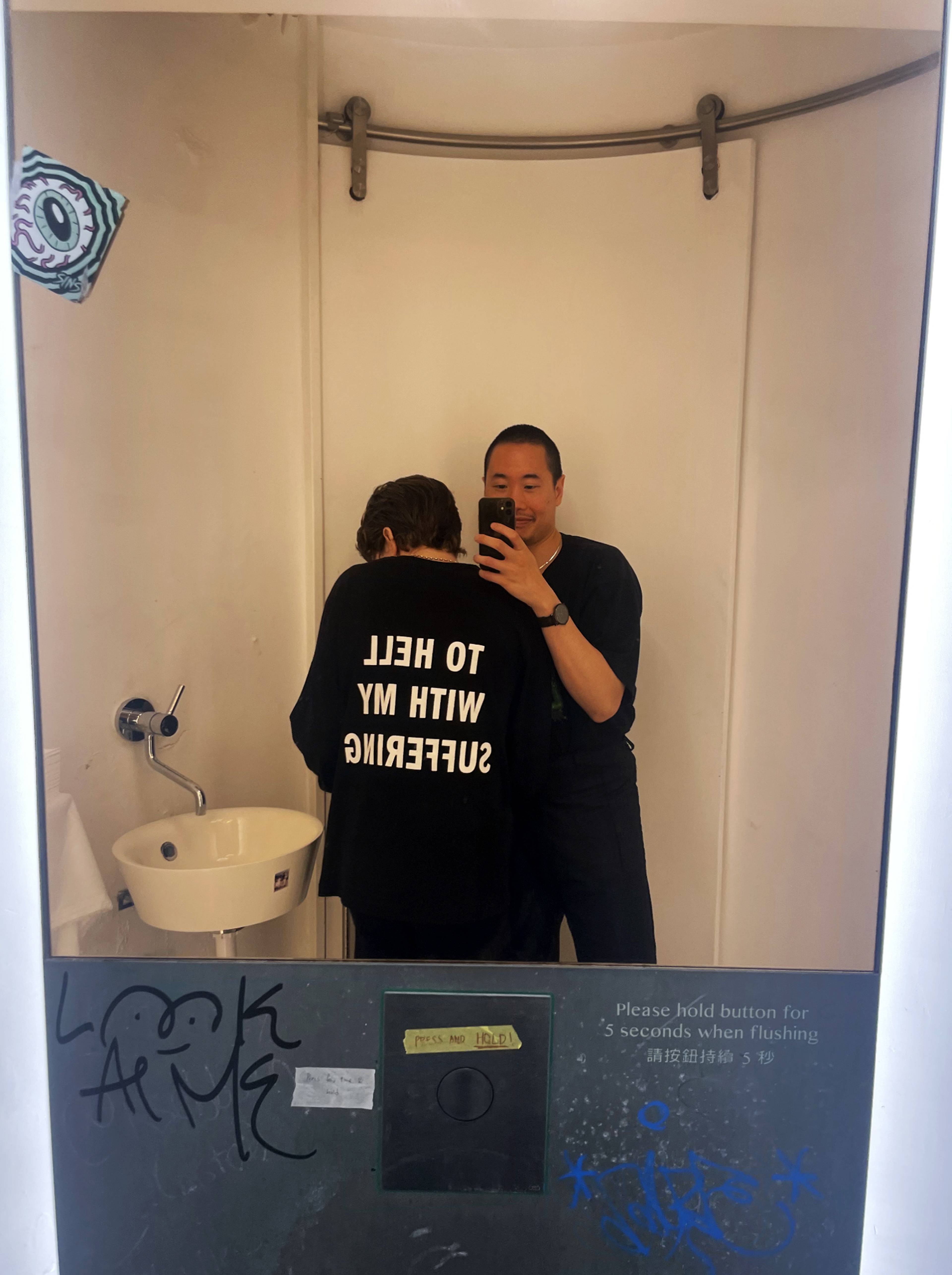

We were going to the opening of Richard Hawkins’s show at Empty Gallery, “The Garden of Loved Ones,” filled with zombies and haunted dollhouses and severed limbs. It was inspired by Tatsumi Hijikata, the founder of Japanese Butoh dance, whose ashen body reappears, paired with corpse-like figures, across Hawkins’s works.

Cut-out passages from Yukio Mishima’s novel Temple of Dawn (1970) were pasted into the collage Decadent Scholar (2018), detailing the eponymous mythical garden where citizens kill and eat their loved ones. “Following the death of the god of beauty, one can recall the highest degree of sexual excitement,” Mishima’s text reads. The background layer shows a severed head, one of Rodin’s sculptures of the Japanese geisha Hanako. Along the right are two cutout images of Hans Bellmer sculptures: each a contorted body with no head or feet, their fat squishing out, trussed in shibari.

Richard Hawkins, Decadent Scholar, 2018, collage, 74.5 x 66 x 2.8 cm (framed). Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Buchholz

What happens when an Asian American looks at a white man’s view of the Asian body? Hawkins told me that the collages begin with desire, a desire for the other, for the Asian body. And by desiring an Asian identity, through Hawkins’s desire, the Asian body returns to me as a corpse, discombobulated and fragmented.

I was born in 1988, the year before the 4 June massacre sent tens of thousands of refugees to Hong Kong, then under British jurisdiction. A California child of Hong Kong emigrants, I would never be able to conceptualize an Asian identity for myself outside the Western gaze. For me, there could be no recuperation, the Asian subject was dead on arrival. But now, in the territory where my mother was born and my father immigrated before Mao rose to power, my connection to Asia was not dead but undead – haunting me.

At the “Garden” opening, I descended to the 18th floor’s reception room. Windows beyond a room divider showed a southern view of the skyline of another island, whose name I didn’t know. In the dark, I couldn’t see the buildings themselves, but the lights suggested the buildings’ shapes, like the Chinese scroll paintings that delineate bamboo branches with color rather than contour. I couldn’t tell you the names of these buildings across the water, but I still felt a memory of an origin I had been expelled from, a longing for a place I never called home.

2.

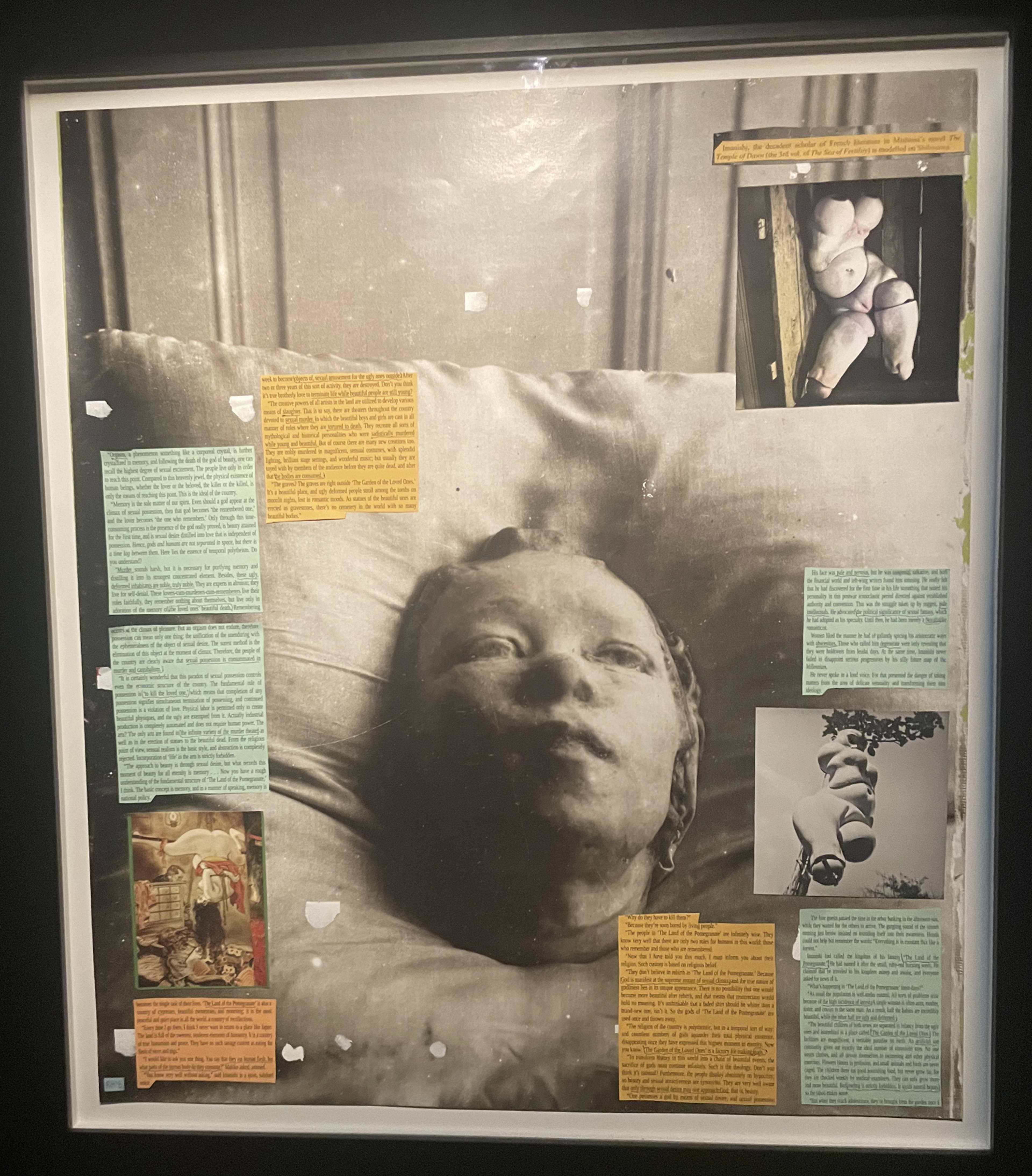

We arrived at the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre for Art Basel Hong Kong. On the third floor, people lined up to take photos with a car covered in brushstrokes, or images of brushstrokes, by Julie Mehretu. Printed on the wall nearby, a quote from the artist’s describes the BMW as “about invention, about imagination, and about pushing limits of what can be possible” – a reminder of art’s boundless possibilities to satirize itself while still looking you straight in the eye.

Julie Merehtu for BMW, Art Basel Hong Kong, March 2025

The art world’s eyes were watching the sales, a bellwether for the Asian market. Everyone was optimistic, and everyone was tired. Everyone was talking about tariffs. “People aren’t serious, they’re looking for something decorative,” one New York gallerist told me upstairs. “They’re not asking anything about the artist.” Downstairs – among Zwirner, Hauser & Wirth, and Gagosian – deals were getting made. I saw a gallerist at 47 Canal who couldn’t chat because she was texting a collector on WhatsApp. “I’m making an offer right now,” she said.

Like Frieze or the Armory, late takes on Abstract Expressionism – zombie formalism, and very good paintings by the likes of Albert Oehlen and Jacqueline Humphries – dominated the booths. But unlike in New York or London, the style has historically taken on a politicized connotation in Hong Kong. Ab-Ex was banned in the PRC throughout the Cultural Revolution, when Socialist Realism was adopted as the official aesthetic of the Chinese Communist Party. In direct opposition to mainland agitprop, Taiwan and Hong Kong fostered their own Ab-Ex movements, fusing the idiom of US action painting with guohua, a tradition of abstracted landscape.

After fifty years of Japanese colonization, mid-century artists from Hong Kong and Taiwan began using Ab-Ex as a coded critique of Communist China, because it was a style borrowed from capitalist democracies. Artists like Liu Kuo-sung advocated for New Ink Painting, which drew continuities between pre-Communist Chinese ink painting to contemporary forms of action painting.

Lee Chung-Chung, The Fortune of the World, 2017, ink and color on paper, 137.5 x 278 cm. Liang Gallery, Taipei

At the booth for Liang Gallery, based in Taipei, I saw The Fortune of the World (2017), a painting of ink and pigment on paper by Taiwanese artist Lee Chung-Chung. Unlike Pollock or de Kooning or even Joan Mitchell, Lee’s compositions work around negative space, her mountainous forms emerging from and organizing around white space. Historically, Chinese painters sprinkled ink into puddles of water on paper or silk, and worked the composition by guiding a series of controlled accidents. In the 19th century, Chinese artists saw ink abstraction to be superior to naturalism, which is what craftsmen did for families who wanted portraits. While it took the West centuries to discover abstraction, Chinese ink painting is millennia old. Abstraction might belong to China more than it does to France or the US.

Yet what was clear at Art Basel was that Abstract Expressionist paintings, like capital, can travel anywhere in the world, to any context, any art fair, and still hold their value. By the week’s end, paintings by Asian abstract artists like Yayoi Kusama and Zeng Fanzhi went on to sell in the millions. The fair was going as planned.

3.

Someone was always wearing a suit. Someone was always wearing Issey Miyake. On the street, I ran into a friend who said he was on his way back from a $5,000 steak dinner with a banker he met through Alcoholics Anonymous.

On Tuesday, Drew and I went to a party at Current Plans, a DIY art space on the third floor of the Remex Centre. Art installations and projections took over the interior, while a large concrete rooftop garden hosted chain-smoking ravers and DJs who mixed post-genre gabber and deconstructed club, backdropped by unoccupied residential towers scaffolded in bamboo and Tyvek.

View of Current Plans

I found my friend, a DJ and sound artist based in Hong Kong, who had just done a live performance the night before at the M+ party I went to. “We were going to invite people from the audience to write notes on the installation as part of the performance, but they told us we couldn’t do that,” he said. “They thought people might write political slogans.”

“Did you submit the proposal to the government for approval?”

“No, it was the institution who said that,” he clarified.

“Oh, it was M+.”

A cloud of self-censorship has settled over Hong Kong since the National Security Law was passed in June 2020, in response to protests reportedly attended by 1.7 million people – or 20% of Hong Kong’s population. The new law, which legalized the extradition of Hong Kong dissidents to be criminally tried in mainland China, deliberately uses vague language to keep people policing themselves; it’s anyone’s guess what can catch the censors’ tripwire. Simply saying “Free Hong Kong, revolution of our times” in public could get someone jailed for up to ten years.

My friend told me that, at the end of his closing set at Berghain in Berlin, during 2020’s CTM Festival, he played a Hong Kong protest song on his violin. People in the audience who knew the lyrics sang along.

“But the label didn’t like it,” he said. “They think the protests were started by the CIA.”

I, too, thought the protests were at least lubricated by the CIA – but I didn’t say so. “The protests were still real,” I added.

In the past six years, pro-democracy newspapers have been shut down. Artists and intellectuals announced on social media they were leaving Hong Kong. By August 2021, 90,000 people had emigrated. I kept hearing the phrase, “Anyone who could leave already has.” At Current Plans, I felt like I was dancing in a Hong Kong that no longer was, a kind of palimpsest that remained after the country’s identity was erased. “There is so much going on, but no chaos,” a curator told me. “Where’s the chaos?”

View from the terrace of M+, Hong Kong, March 2025

The music shut off at 1am, when two policemen stepped onto the roof garden. I saw someone film the interaction on his phone. Here was a generation that rejected the promises of visibility politics and were trained to turn the cameras away from themselves and onto the abuses of the state that had already sponsored the total surveillance of civilian life.

In the US, the only Chinese cops I’ve ever seen were young; this pair was older, with salt-and-pepper hair. I was surprised at the sight before I knew why: They looked like my father, or how I might look once I am my father’s age.

4.

One evening, I visited my aunt and uncle in the New Territories, near Kowloon. They lived in the Ocean Shores towers, which had a view of the water from its upper floors.

“You know, I had a stroke,” my uncle said, as he welcomed me into the apartment. “I move so slowly now. I can’t walk.”

“You look good,” I said.

“I look good, but I’m not,” he said. “I speak so slow. I’m struggling.”

My uncle and aunt and I sat on separate couches. Donald Trump pontificated about tariffs on the muted TV. My aunt with her tattooed eyebrows watched me with her mouth slightly open. She looked older to me than my grandmother had in the years before she’d died, even though my aunt was only in her seventies.

“Sam Yee-ma was in the nursing home for two months because of a neck injury,” my uncle said about my aunt.

Silent until now, my aunt stirred and said, “All the old people complained about how they wanted to die. They stopped eating.”

My uncle gave me a sideways glance and started laughing. “Everybody wants to die.”

They looked older than when I’d visited them twelve years ago. During a month-long stay with them twelve years earlier, we’d gone to a shopping mall, where we saw a red metallic balloon dog by Jeff Koons. I told them, “Did you know that this is worth tens of millions of dollars?”

“This?” my uncle said.

We stared at it with contempt. Then my aunt touched it hesitatingly. So did my uncle. And then I slapped it. My uncle began slapping it, too. Then my aunt joined in. My uncle grinned in satisfaction. The three of us stood there, slapping the Koons, sending smacking sounds gleefully around the escalators, punishing it.

5.

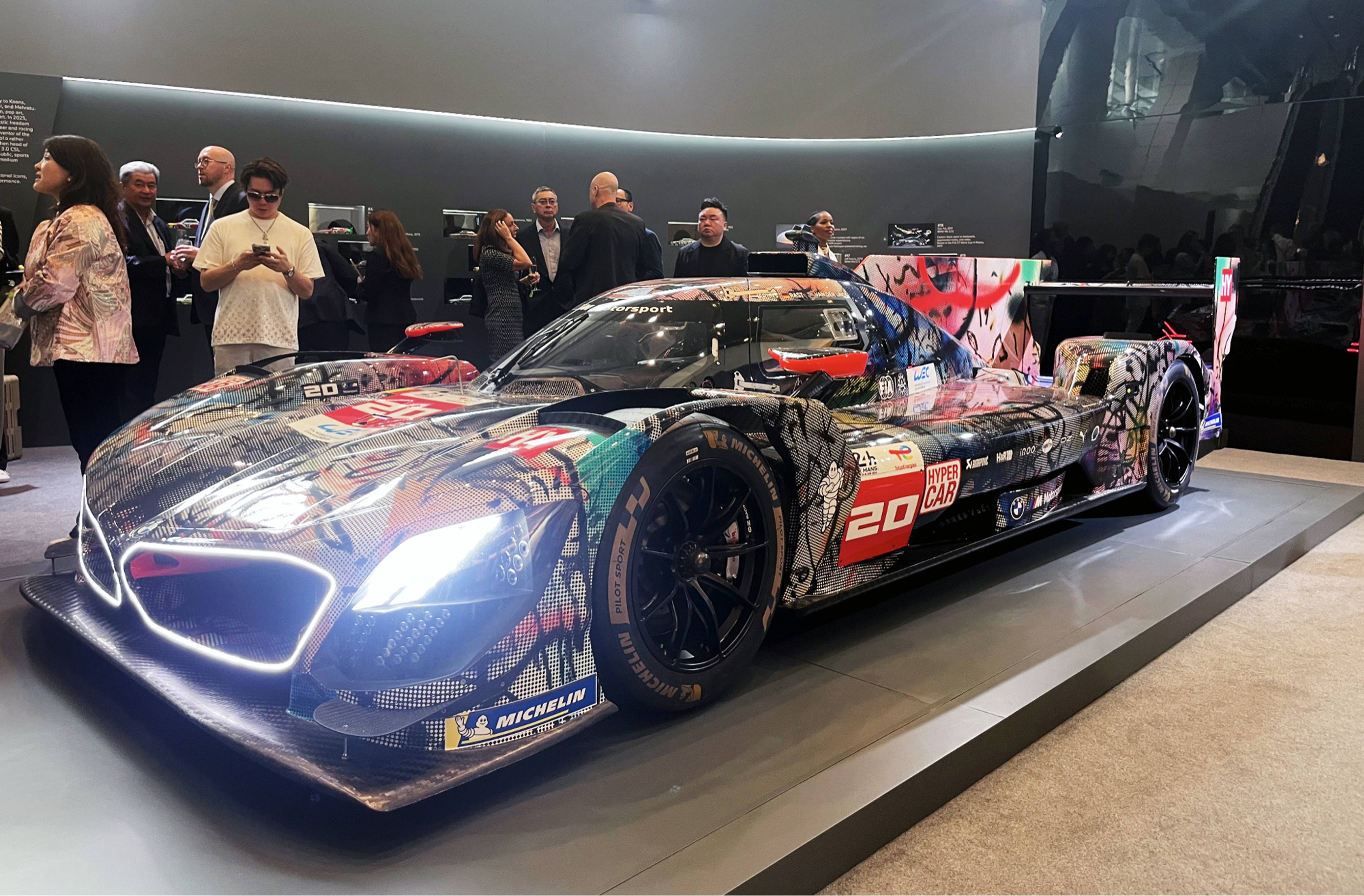

Drew and I ascended the escalator at the Henderson skyscraper as a Koons swan loomed massively into view, protected by stanchions. The interior smelled like money: clean and kind. The champagne-colored bathroom stalls looked like space pods for astronauts to sleep in.

The exhibition for Christie’s 20th and 21st Century Art auction spanned two floors. The walls were painted midnight blue, and spotlights illuminated each canvas, which glowed as if they were lit from behind. People spoke in whispers.

Work by Jeff Koons at The Henderson, Hong Kong, March 2025

Hanging near the exhibition’s entrance was 05.09.2003 (2003), a painting by Zou Wou-Ki, the godfather of greater Chinese Abstract Expressionism. At Basel, I saw only one Zou painting; at Christie’s, I saw five. Having lived and taught in many different cities, he is claimed equally by mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and France. I happen to have a small canvas print of one of his paintings, about the size of my head, hanging in my living room in Brooklyn. But in person, the large canvases confront the body in a way a print never can. I walked up to the chartreuse-tinted painting, my nose inches away. I was overcome by its majestic scope, yet I still had this twist in my stomach acknowledging how much this style owed to the West, where Zou is treated as second rate to, say, Joan Mitchell, whose abstract paintings made similar designations of space and landscape.

When I was a child, I considered Western culture superior to the Chinese culture I inherited. My mother often took me to museums that schooled me in European painting. Chinese opera sounded like a traveling sideshow in comparison to Beethoven’s 9th (1824). China was a backwater, and the West was good, I learned from my father, who once believed in the free market as a salve to authoritarianism. I knew people in my church who swam by moonlight from mainland China to Hong Kong to flee persecution. Yet only in a Chinese context have I heard activists supporting capitalist democracies described as “rightists,” many of whom, like my father, fled the Cultural Revolution to the US in the 70s. Yet it was precisely this new Asian American right who, just fifty years later, would go on to support a federal administration that would prosecute academics, extradite political dissidents, and suppress speech critical of the hated regime.

Zou Wou-Ki, 05.09.2003, 2003, oil on canvas, 95 x 195 cm. Courtesy: Christie’s, Hong Kong

So I began looking back into modern Chinese art, which is what I was looking for in Hong Kong. What I found were artists who were just as enamored by the West as I was when I was younger. Together with Zao, Chu Teh-Chun (who was also showing at Christie’s) and Wu Guanzhong were dubbed the “Three Musketeers” of Chinese painting, precisely for their recognizable incorporation of Western Ab-Ex. The Chinese New Wave artists of the 1980s explicitly borrowed from American Pop Art and Neo-Expressionism to illustrate political allegories as literal as the Socialist Realism they rebelled against. It seemed any artist who was critically acclaimed happened to have spent time in the East Village or Paris.

All modernisms are amalgamations of various influences, but why are only non-Western ones framed as such? In my education, French Impressionism was praised not for its being influenced by Japanese woodblock prints, but for its originality of style. Originality. Was there a single, original Chinese art movement since China lost the Opium War that didn’t, in some way, borrow from Europe or the US? What about New Ink Painting? Or asemic literati painting? Why did I always believe that Chinese art history, according to the Western canon, ended when it opened to Europe in the mid-19th century? Is there a Chinese modernity without a Western bow?

The day after Christie’s exhibition, their 20th and 21st Century evening auction raked in $73.3 million. Meanwhile, in America, stock markets plunged, inflation rose. If China had borrowed capitalism from the West, it now seemed poised to eclipse the West. Enter the Chinese century.

6.

On one of my last nights in Hong Kong, I was on the tram with Kaitlin, the director of Empty Gallery, whom I had met earlier that week. We had agreed to go to the opening of another fair, a slew of performances, and yet more parties, where we were supposed to meet friends. But when the tram neared our stop, we locked eyes.

“I don’t really feel like going anymore?” she said.

“Let’s ditch,” I said.

Rain spat on our foreheads through the open windows on the upper deck as we rode the tram to the last stop in Shau Kei Wan depot. We walked out into the light rain, passing neon signs – yellow, cyan, purple, green – glowing in the drizzling rain.

We talked about the Hong Kong art world. “It can feel provincial,” Kaitlin complained. She had a perfect American accent from watching MTV’s Daria and Cartoon Network, and discovering American pop-punk as a teen.

“I think that’s kinda cool. Like a for-us-by-us mentality. The Hong Kong art world should be for Hong Kong artists. Some of those Asian paintings I saw this week would rarely, if ever, be exhibited in New York.”

We waited for a crosswalk to turn and headed down into the mass-transit railway’s vast network of escalators and tiled walls. “Maybe Hong Kong being provincial is a good thing,” Kaitlin said.

We eventually got to her apartment in Causeway Bay, and ate ice cream on her couch. “I always feel like I need to put on music or something, but silence is nice,” she said. We were talking about our lives with the intimate abandon one only does with strangers, the kind of heart-to-hearts I thought I stopped doing in my twenties.

“I think friends are like mirrors,” she said as rain tapped the glass behind her. “It’s like that Velvet Underground song. My friend used to play it and talk about how the best parts of our friendship were like a mirror, in that we need each other to reflect what we can’t appreciate or understand about ourselves without the other.”

Perhaps it’s my cynicism that believes the self can never quite see reality outside of its own projections onto it, as if life was lived in a hall of reflections. But mirror images, according to Lacan, can make us whole. I liked how Kaitlin’s formulation made it sound relational: The other intervenes and makes the self appear alien to itself, a foreigner in its own skin, having been seen by the other, a lover. In this way, Hong Kong was a kind of mirror. I felt a nostalgic longing for this city then, before I had even left, but even more now that I am gone. Show me a picture of concrete residential towers at any time, and I can tell you about wild boar at night and gold-flaked caviar and cockroaches with wings. I thought of a Mishima line I had read in one of Hawkins’s collages: ““Memory is the sole matter of our spirit.”

The next day, I went to Empty Gallery’s yearly rave, exhausted, catching myself telling the same story twice to people I had just met – a sign that I had been too long in Hong Kong. I was rude, and I left early without saying bye to anyone. It was only when I got to the airport that I saw a message I had missed from Kaitlin the night before. “Let me know before you leave the rave tonight! I want to say goodbye properly.”

But it was too late. By the time I saw the message, I was already gone.

___