An art fair is like visiting Los Angeles: agonizing, until you relinquish all criticality and become, in both instances, a chronic bearer of sunglasses. I get sick once a month, sometimes twice. I get sick so much people think I’m lying about being sick. The previous two art fairs I attended, I spent the final days of my trip sequestered in a hotel room, with a 37.8 °C fever, in complete darkness – because somehow the power has gone out, twice. In Miami last December, there was a subterranean electrical explosion in South Beach. This year I bumped into the breaker box.

Art fairs function as metronomes for the global art market, marking half beats between the kick drum of the auction circuit. Despite fairs spawning in most major cities, Art Basel – recently the victim of the tasteless dub “Basel Basel,” so as to not confuse it with its sister fairs – still holds the title of the nexus of the market.

I’m here with my gallery partner to present a set of paintings at Basel Social Club. It’s the first night, and we meet with a couple of artists and dealers who are also here under the alibi of presenting works. We eat ramen priced at thirty-eight US dollars. There is a reluctance to fully embrace the concept of the art fair. They have not quite given in yet to the axle of international exchange that will facilitate the motion blur of the next week.

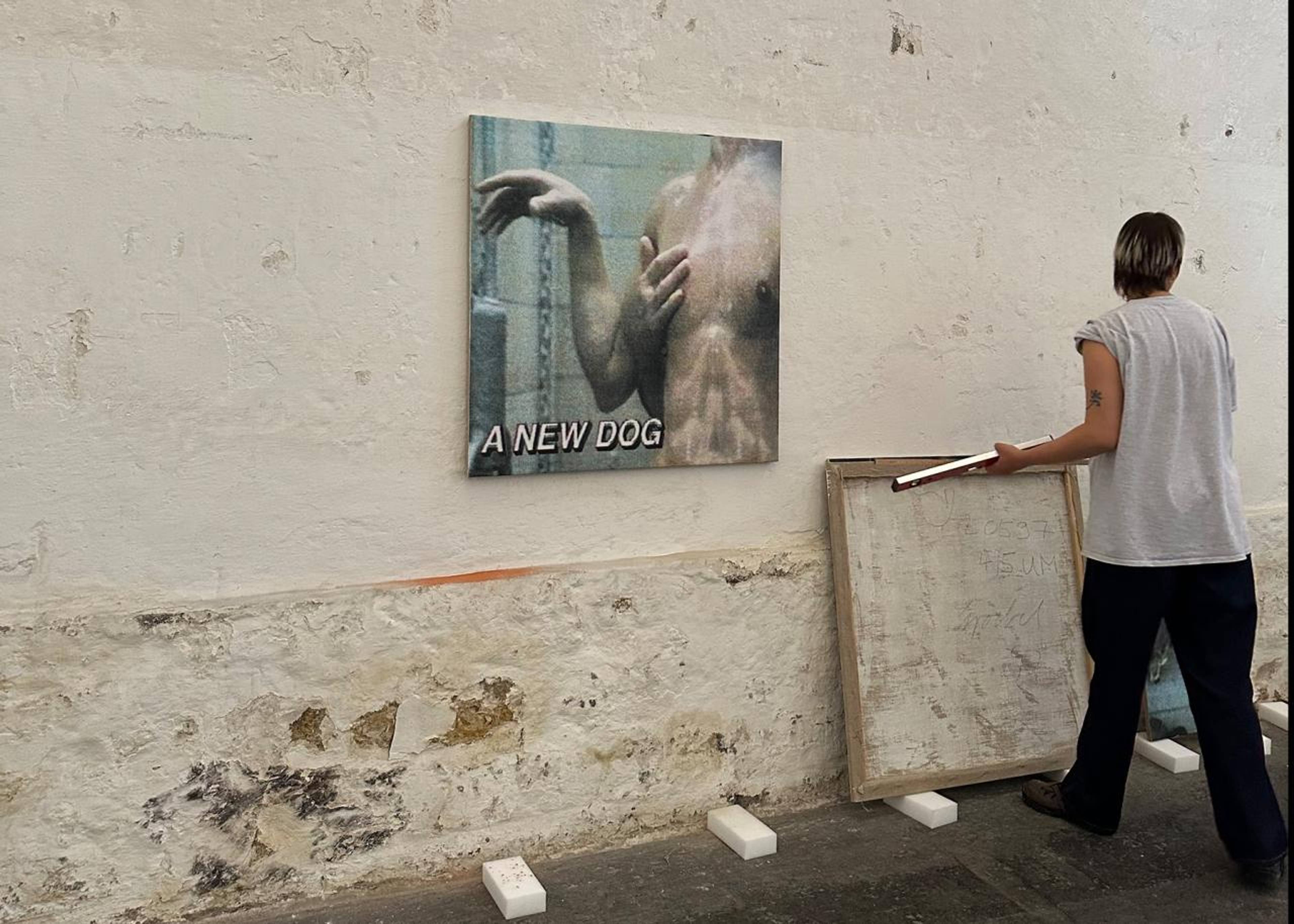

Installation of a painting by Matthias Groebel at Basel Social Club

Basel Social Club

Basel Social Club is the first fair to open. The brainchild of the Parisian dealer Robbie Fitzpatrick, Basel Social Club boasted a gallery participant list whose numbers rivaled that of the main fair. Located inside an industrial concrete compound formerly home to a mayonnaise plant, the fair sprawled across four floors, each floor flanked by a fully stocked bar. A party fills the street. There is a surprising absence of suits here; from each respective area of the globe, attendees seem to be living under the idea of an international downtown. The outside bar area necessitates a dodge-and-weave through tightly condensed congregators, your drink tucked into your armpit to avoid spills. It’s the first night: Everyone is still fresh, a little nervous, and decidedly unsure how many kisses on the cheek are appropriate in Switzerland.

“No, no, two kisses only please,” I’m told the next day on my doubling back to the left cheek of a Viennese gallerist.

It’s Wednesday, the preview day of Liste, the preeminent satellite fair in Basel. I stop by the booth of a young New York dealer, who has four thousand francs in an envelope sitting on her desk. “They wanted to pay cash, and I don’t make the rules.” It’s unclear to me whether the rules she did not make explicitly prohibit that.

At around 11pm, there is a citywide descent on a club in what was referenced more than once as the “Bushwick of Basel.” Drinks are seventeen francs, which is equivalent to 22.4 US dollars. I have six drinks, and relative to the crowd, I am sober. I run into an artist from Vienna who’s just taken ecstasy. “It’s fine,” she says, “much stronger than last year.” Such a measured appraisal of euphoria, I decide, is something unique to Europeans.

I begin to speculate Silently how moral outliers become ritualized into a divine tradition. Like mob initiations. Or the upkeep of female virginity. OR Suicide bombing.

At around 1am, an art dealer tells me that they upsold a four-thousand-dollar piece to a collective purchase of thirty-eight-thousand worth of artwork, and showed me the texts to prove it. Another dealer sold out his entire booth to someone he says “isn’t involved in the most dainty of industries,” but I don’t ask. It’s as if the sale and purchase of artwork is insulated from the traditional moral rubric. I begin to speculate silently how practices seen as moral outliers in turn become ritualized into a divine tradition. Like mob initiations. Or the upkeep of female virginity. Or suicide bombing.

The sun comes up here around 4:45am. The crowd toggles off, and a silent herd moves through the exit gates.

Sam Marion

The next day, I’m denied entry into the main Basel fair, as my press pass only provides clearance into the second-rate VIP slot: a well-timed reminder that I am not important. With a few hours to kill, I drift across the convention center “Unlimited,” the installation-focused subsidiary of Art Basel. The operative principle here is scale, and it works – big things are impressive, and big, expensive things are even more impressive. I spend the most time in Guillaume Bijl’s 1:1 recreation of a mattress store. Bijl is an artist that understands the needs of the viewer, and here, they just need to lie down.

Entering the fair now with a proper timeslot, the air is taut. Like SAT-test-day taut. On preview day, social interactions with any non-collector civilians are, at best, a distraction and, at worst, malicious. One might find titans of modernism in the same eyeline as a painter two years out of their MFA. Gone are those concrete exhibition pantheons, gone are the curatorial wall texts that predetermine context, gone is an appropriate amount of air-conditioning. Here, work is viewed in a vacuum of context, but beautifully. A nice Luc Tuymans. Too many Fontanas. A Heji Shin, an Issy Wood. Some castaways from the French moderns.

After about an hour of putzing about, I break my internal treaty of non-disturbance and sit down with a friend at his booth. He entertains my little musings about context before chasing down a woman fully clad in Chanel. I’m left at the table with his assistant. She applies makeup with a hasty precision – “war paint,” she says, before snapping her mirror closed and following her employer.

At around 6pm, exhausted from a four-day maelstrom of politeness, I attempt to do a kind of “time-out” dinner with some artist friends; a palette cleanser, coffee beans in between buckets of the scent “Portrait of a Lady.” No luck, right back into it.

Instead, I end up at a dinner where I know nobody. Sensing an internal charm shortage, I leave early and take a separate route to the following party. On the walk, I listen to the entirety of the 2004 crust punk album Fuck World Trade by Leftover Crack. The third song on the album, “Life is Pain,” served as my alarm clock for three years of high school. As I walk alone in the dark, I realize how convenient it is that a conspicuous display against international trade can also serve as a palliative against homesickness for my juvenile identity.

The three tenants of good gossip – cruelty, lust, and bravado – play in wonderful harmony.

There are no artists at the next party. It’s easy to clock how buttoned-up this will be. The conversational style here shifts to one akin to speed-running a video game, wherein players mash the fast forward button through the scripted character interactions in an effort to discover if potential advancement will be stored at the end. This is not to say that these interactions are more transactional than a typical professional conversation, but the pressures imposed by time yield an economy of sentiment that, once understood, has the potential to streamline social interactions.

It’s now late enough that I’ll skim a few hours off my previous night’s itinerary as I speak to my mother on the phone the next afternoon. There are six people in a very large domestic bathroom, but only one person sitting cross-legged on the floor. Earlier that week, an advisor had pointed her out to me, from across a party, as “meteoric,” he gestured, changing the direction of his pointed finger from her to the ceiling. “The horse everyone is betting on.” I still don’t know who she is, and – with excessive chemical encouragement – neither, it seems, does she. Speaking to nobody in particular from her tile podium, I stoop my posture over to tune into her treatise. Her life goes like this: great dad, Swiss boarding school, a brief stint as a ballerina, painting, school, master’s, more painting, supposedly famous musician boyfriend I’ve never heard of, small gallery exhibition, first auction result miles above estimate, big gallery exhibition, big gallery exhibition with a little sculpture (didn’t take well), auction, auction, present day.

The Beyeler Foundation garden. Rumor has it, the cows that graze nearby are bussed in once a season for the fair.

Central to the allure of a late night like this is the partition between social classes thinning into a reciprocal membrane. On a Tuesday, gallery assistants may slip into the thousand-dollar cocktail nights on the Rhein hosted by the collecting class, and on Wednesday, the collectors themselves may slip into some smoky promenade in search of an elusive guest list. With the wilderness of hierarchy sometimes too difficult to read, your mere presence at the fair is the only necessary credential to participate. Those governing tenets between being and appearing become blurred, and it becomes a wonderful place to be someone who you might not be just yet.

Her story stops abruptly, and a few seconds of unexpected silence insinuate that I’m on the hook for a response. I stumble to tell her that it seems she’s lived a very blessed life, but she cuts me short with a bit of unintended lyricism: “I feel so lucky that sometimes I wonder if I accidentally sold my soul to the devil.” She then seems to dissolve into the momentum of her own story and spends the next few minutes fumbling around in her bag for cigarettes. When I leave, not only is the sun up, but it’s hot outside.

Our neighbor sells a painting for more than my yearly rent, in sandals, and a few hours later, I do the same while holding an empty beer can.

I spend the next few days manning our section with as much formality as the fair calls for. Basel Social Club, where we’re exhibiting, takes a kind of “hair down” approach to an art fair; thus, booth attendants are not required to sit as anxious stewards of the artwork. Most gallerists who are exclusively showing here wander around the bar between appointments. Our neighbor sells a painting for more than my yearly rent, in sandals, and a few hours later, I do the same while holding an empty beer can.

Thoroughly exhausted, our own booth sold, and ready to go home, I make my way to an impromptu assembly at a local watering hole. Here, the attendant gallerists are in good spirits. Most sections sold well, and the work in the main fair is “surprisingly fun to wander around in.” With the biz now complete, the rest of the week is mostly postcoital pillow talk. The tenor of interactions drops an octave; and at this stage, one may even be asked about what their siblings do for work or whether it was nice growing up in rural Colorado. The necessity of maintaining guarded conversational patterns in the previous days has yielded an overcorrection of informality. The three tenants of good gossip – cruelty, lust, and bravado – play in wonderful harmony.

Sales at a fair operate according to principles of access; therefore, all business is front-loaded into the first few days. After the first two days, the dust settles, and a few days later, the dust congeals into what’s essentially summer camp. Abandoned by the bosses, collectors, and other assorted dignitaries, the sales assistants, small-time gallerists, and underlings, et al, are left to their own devices, creating a hodgepodge itinerary composed of swimming in the Rhein, and nightly outings to a bar whose theme is dedicated to the American TV show Friends.

I stop by the main fair one last time. It’s now Public Day: fanny packs and skateboards. Most of those stationed at the booths don’t look up from their phones, shoes kicked off, legs crossed. Rogue itches on the calf are entertained while maintaining eye contact with one’s computer screen. Toward the end of my loop, I enter a booth where the aura of desperation from the owner is so palpable that he seems to be warding off visitors. His outfit is so classically unkempt that he appears as though he’s auditioning for the role of his current position: Man Who Realizes He’s Now in $200,000 of Debt . For my first time ever, I’m offered a price list without asking. His assistant stands with her back pressed against the corner of the booth with an expression of resignation that could only mean an impending horizon of actual resignation. Like, resign, quit, quit as soon as the jet bridge connects to the plane.

The Naturbad – a public pool, believe it or not.

A friend earlier that week had equated the selling of work at a fair to the trading of derivates: a life raft of good odds in favor of the peddler. The abundance of sweatless, trim dealers sitting comfortably in the green seems to verify this anecdote. But of course, there are a number of someones sitting somewhere inside this convention center that must bear that opposing percentage, that small, single-digit red number signifying devastating financial ruin. I tell this man at his booth that I am not in any kind of financial position to be buying artwork, but I wish him the best of luck. He brings out an iPad to scroll through more affordable options. As I leave, I’m overwhelmed with that grave reminder of consequences that’s accessed first as a child, watching your friend break his femur on a bicycle. For just a second, all the money here seems very real, and death seems less like an avoidable condition.

Swimming at a local pool with a friend, I develop a small tickle in my throat. Twenty-four hours later, I have memorized every stucco pattern on the ceiling of my AirBnB bedroom. It is difficult to not view an inconveniently timed ailment as a judicial appointment from God, that perhaps the way one has been living is caustic enough to the spirit that a skyward deity must confine one to a poorly furnished Swiss apartment. The bedroom has no blinds, so I wear sunglasses alone in bed while my colleague visits what appears to be the Swiss Alps, judging by his Instagram story.

The Rhine at sunset

___