It’s been a week since a spaceship of art aliens descended on Paris to wreak their havoc, straight out of Alex Da Corte’s deflated Kermit the Frog head at Place Vendôme. Think Tim Burton’s Mars Attacks! (1996) but slightly more stylish. ART BASEL PARIS. Or, leaving the invasion-drama metaphor to one side, maybe it felt more like the mass of chipped cups, trinkets, and burnt-out Tefal pans Merlin Carpenter hung up at di volta in volta in his show “ART PARIS BASEL.”

In any case, I am (still) confused and tired and in need of mousse, like Hélène Fauquet’s shells glued to photos of bubbles at Ulrik (Paris Internationale). I have been sucking images for too long. Not just images, but objects, booths, texts, vibes, glances, gossip. Sucking, beating, and frying them for their sense, here is an attempt at a critical crêpe. Sorry if it’s burnt.

Merlin Carpenter, “Holiday Homes 5-8,” 2025. Installation view, “Art Paris Basel,” di volta in volta, Paris, 2025. Courtesy: the artist; di volta in volta, Paris; dépendance, Brussels; and Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York

Hélène Fauquet, Turbinae, 2025, inkjet print, seashells, frame, 21 x 16.5 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Ulrik, New York

It is news to no-one that Strong Men have been terrorizing the globe in micro and increasingly macro ways. If the week of Art Basel Paris taught me anything, it is time for everyone to liquidate their masculinity. Cash out of the New Man. There are problems. Sell off before they become bigger. For within circles that still hold onto their supposed ideals of democracy, we have a crisis of representation. Not to mention the return of the himbo.

These things are related, if I am to believe the Ceccaldi brothers. For their duo presentation at House of Gaga (Paris Internationale), Nicolas showed exquisite pastel copies of François Le Moyne’s 1729 portrait of King Louis XV, squashing the soft folds of the teen monarch’s portrait into a landscape that, viewed according to today’s aesthetic codes, looks like a despot as feminized-meme-baby, and subtly so. Behold … the New Man? This satire felt productively inverted in Julien’s comic vignettes, which put his gender-whatever comic-book characters Francis and Solito into states of sweet humiliation: depicted as thumbs, hung up in closets, green and pouting. The two bodies of work seem like exercises in understanding how propaganda might operate today, from the narratives of the self to the representation of sovereign power, squashing subjectivity in between.

View of Nicolas Ceccaldi, House of Gaga, Paris Internationale, 2025. Courtesy: the artist and Gaga, Mexico City

Oliver Coran, Untitled, 2024, acrylic on plastic, 152 x 202 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Lovay Fine Arts, Geneva

Over at Lovay Fine Arts (Paris Internationale), this new body politic was fleshed out in works by Oliver Coran. He paints icons, pin-ups, and thirst traps across the surface of their new material: plastic. Hidden among the compressed layers of gestural mess, I hunted for the naked miniature figures. They conveyed the intimate anxiety of being looked at, an insecurity blown up to scale in Untitled (2024), where a trans man shows me a fold of fabric or a hard dick. It’s a handsomely vulnerable self-portrait. Days later, I think of today’s uber-femme Hailey Bieber embracing the trans-ness certain haters have flung at her: “Some of the most beautiful people in the world are transgender.” Being beautiful means being complicated. Hailey gets it. Oliver gets it.

So do Zoe DeWitt, David Hoyle, and Chris Korda, whose dissonant presentation at Goswell Road (Paris Internationale) was a full serving of pussy-envy-liquid-body erotica and anti-human agitprop. Thought alongside Lucy McKenzie and Reba Maybury’s collaborative project and book Pervert or Detective? (2025), presented by the gallery No Tax, and Dean Sameshima’s exhibition “Portraits” at Good or Trash, strategies emerge. Art is a means to redirect male libidinal desire for domination into form (funny sketches); or, art is a means to lose one’s identity, like a minimal canvas: anonymous torso, anonymous splendor, just a simple city boy.

Zoe Dewitt, David Hoyle, and Chris Korda at Goswell Road, Paris Internationale, 2025. Courtesy: the artists and Goswell Road

View of Reba Maybury & Lucy McKenzie, “Pervert or Detective?” No Tax, Paris, 2025. Courtesy: the artists and No Tax, Paris

Paris boys, or “Gamins de Paris,” organized by Jenny’s, New York, was one of the best shows and best parties of the week. Works were hung in the underground dungeons of goth club Les Caves Saint-Sabin. I went early and watched Richard Hawkins’s agitated montage of ripped e-men masturbating in front of one of those soul-wrenching Francis Bacon paintings (Painting 1946). It was insane, an awkward kind of sexy muck that transfused into other works in the show, even if they were really just décor for the party. Hours later, crowds of cool gamins almost stampeded themselves into the stone floor. An even darker collective work.

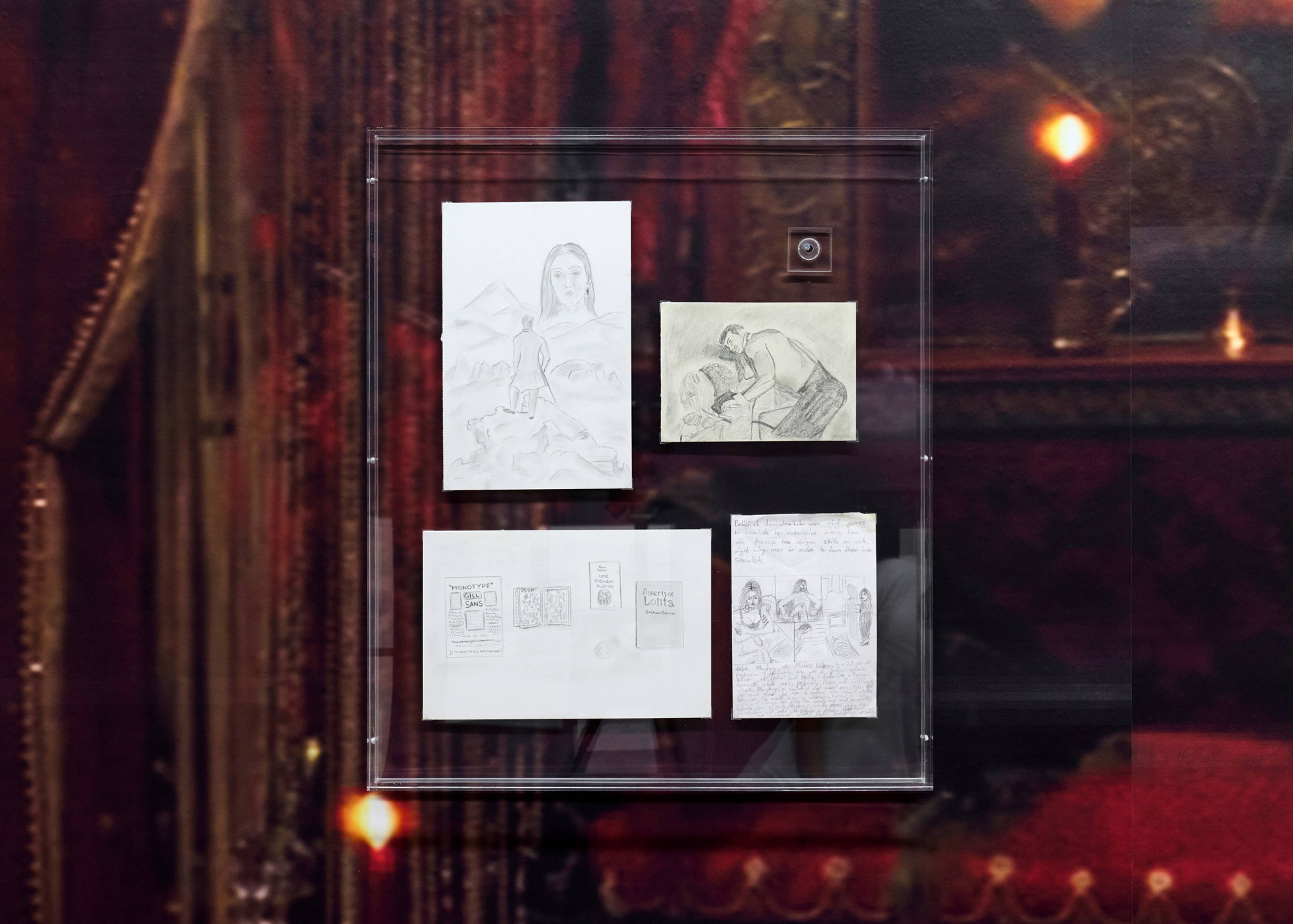

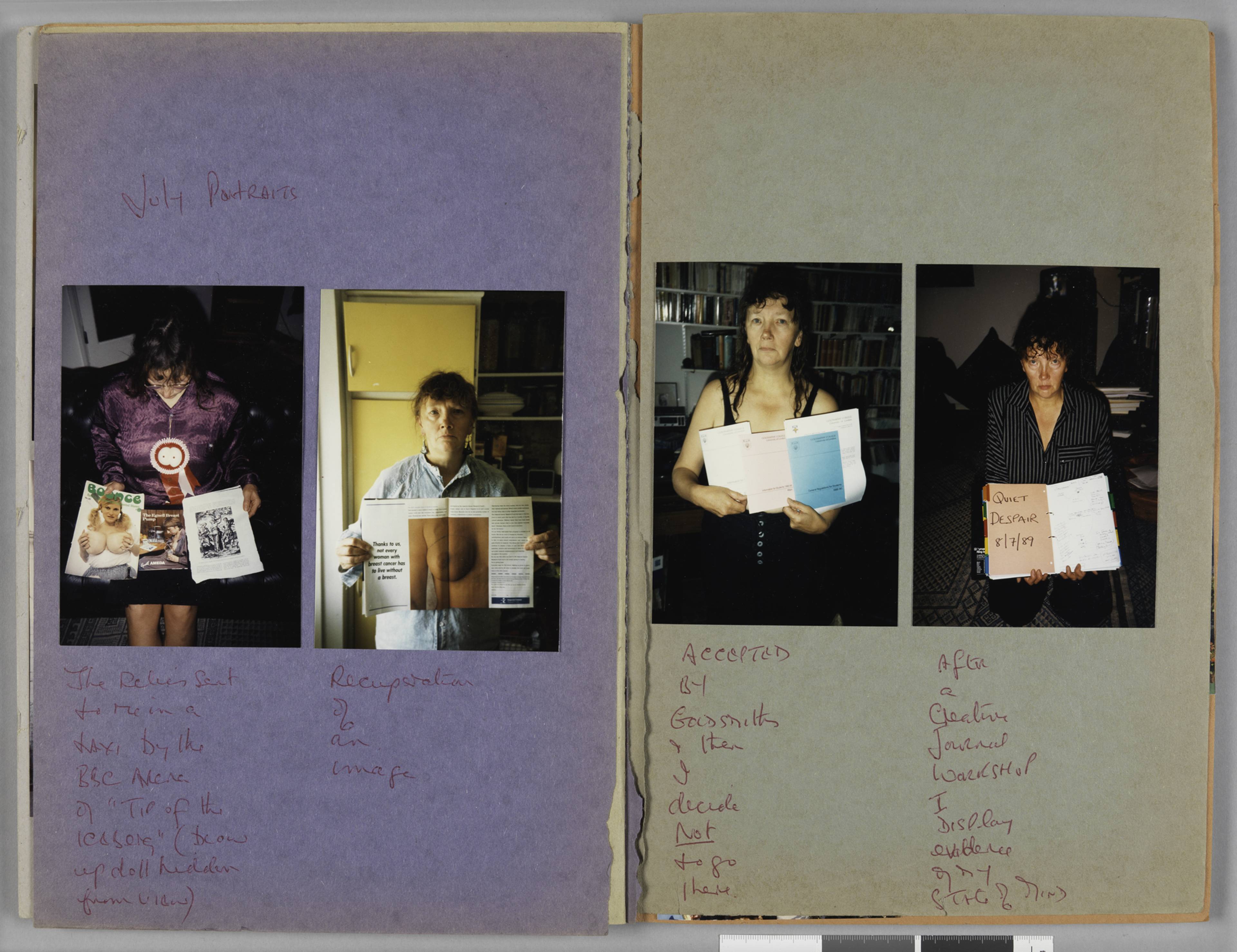

Jo Spence, Scrapbook “1989” (june-november 1989), 1989. Courtesy: Centre Pompidou / MNAM-CCI / Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Fonds Jo Spence

Jo Spence, The Final Project [Specimen Jars], 1991–92, in collaboration with Terry Dennett. © Jo Spence Memorial Library Archive Birkbeck, University of London

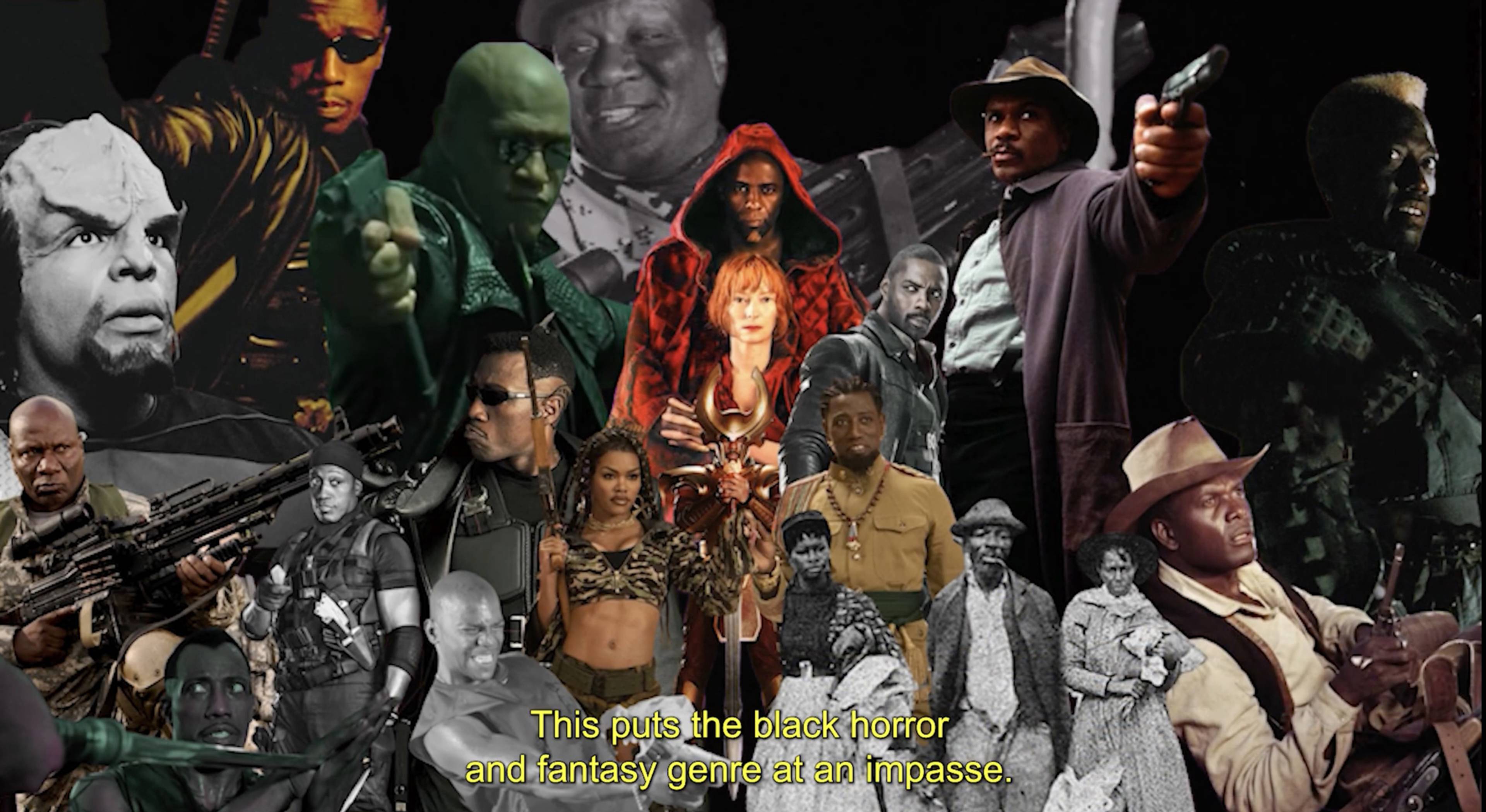

This moment of release was an important antidote to the week’s crowning of masculine virtuosity (part awe, mostly angst, literally terrifying), with major institutional exhibitions for Gerhard Richter (Fondation Louis Vuitton), Philip Guston (Musée national Picasso), and George Condo (Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris). Other remedies included, at Heidi (Art Basel Paris), Kandis Williams’s compelling auto-theoretical video essay A Travel Guide: Black Gothic in South Korean Horror (2025), which splices together critiques of K-Pop, the figure of the Black American soldier, and other military ghosts across her travels in Korea. There was also, at artist-run-space Treize, the very first French retrospective of late British photographer Jo Spence, whose photo-therapy works, documenting the artist’s (fatal) fight with breast cancer in the 1980s, still feel radical today.

Another relief still was Janet Olivia Henry’s presentation with Stars and Gordon Robichaux (Art Basel Paris). Generative methods of critique appeared from across her career, including photographs, hanging lariat sculptures, and the central diorama The Male Art Dependent (1984/2025), a parody of the discriminatory gallery system (including miniature artworks inspired by the likes of Lorraine O’Grady and David Hammons).

Still from Kandis Williams, A Travel Guide: Black Gothic in South Korean Horror, 2025. Courtesy: the artist and Heidi, Berlin

Janet Olivia Henry, The Male Art Dependent, 1984/2025, mixed-media, found and altered objects, wood, acrylic, hardware, 55.9 x 101.6 x 33 cm. Courtesy: Gordon Robichaux, New York and STARS, Los Angeles

As I discussed with my friend S., the highly personal and idiosyncratic logic present in Henry’s works felt very different from all the “highly personal,” oneiric figurative paintings we had been seeing at both fairs. The next day, S. sent me a screenshot of a gallerist’s Instagram story who qualified this trend as “small format oil paintings in earthy tones” – still lives, bucolic landscapes, pleasing portraits with a twist – that, apparently, amount to a new reactionary aesthetic.

I am not sure if I entirely agree; maybe it’s a new aesthetic of restraint? After visiting the Richter retrospective (as I said, terrifying), it’s hard for me to imagine a young figurative painter having the same ambitions as that artist when, in 1988, he painted the blurred dead bodies of the Red Army Faction. Does this hypothetical shift – this need for the (figurative) painter to look away, or to look inside themself – implicitly critique the heroic pretension that an artist might reveal society’s violent contradictions? Or some kind of withdrawal, an elegant form of self-censorship?

Hamishi Farah, The Dead Sea, 2025. Installation view, Maxwell Graham, Art Basel Paris, 2025. Both courtesy: the artist and Maxwell Graham, New York

I found an exception to my false binary at Maxwell Graham (Art Basel Paris), in The Dead Sea by Hamishi Farah (who I profiled in Spike’s Summer 2025 issue, “Vulgarity”). Its rocky landscape reminded me of works I had seen in his current show at the Frac Lorraine, Metz, where the artist presented portraits of pillars of salt. Or rather, of Lot’s wife, a woman from the Book of Genesis, who was turned to stone because she dared look back at God’s unsparing annihilation of her native city, Sodom. Through fastidious, grayscale landscapes, Farah doesn’t show us this destruction – a metaphor for the genocide in Gaza – but refers to it through another kind of grief, for she “who suffered death because she chose to turn.” A grief for looking itself.

In a completely different register, days later, tired and slumped on a couch at Lafayette Anticipations, this idea of art revealing a political unconsciousness returned to me. I was listening to Meriem Bennani’s installation Sole Crushing. Across an entire floor, the artist has assembled percussive instruments from all kinds of flip-flops. After cycling through different compositional arrangements, its joyous stupidity gives way to an ambivalent complexity: inspired by the dakka marrakchia, a folkloric Moroccan ritual, the artist has automated a form of spiritual transcendence. Is this what the dead internet sounds like? The rhythm of an immaterial army? I try to imagine all the feet, all the legs of the invisible, chattering riot.

I downgrade my vision. Imagine just the art world in flip-flops. All the different toes, their hairs, chipped varnish, nail fungi … the sound of the plastic slap. After a week of unhinged energy, maybe this is new shoe choice of Paris, which so wants to be something other than a fetish of old-world inertia. This toes-out freshness is no doubt a result of the city’s growing list of experimental venues for art, be they commercial or off-spaces or in between: Treize, After 8 Books, Pauline Perplexe, Tonus, and Bagnoler, along with more recent projects like Shmorévaz, Good or Trash, Tramps, Agence de Voyage, di volta in volta, Pétrine, Lo Brutte Stahl, No Tax, Essais, Au Cadre d’or, Princesse, Profil, Pony, Aléa, Volonté 93… and I’m sure I’m forgetting many others.

For, as this week showed, the very best flip-flops are improvising artists, like Liza Lacroix and Philipp Farra’s curated group-show “Twin Flame,” elegantly haunting the bar Le Bailly with enigmatic video projections (I still think about Vijay Masharani’s Void in the eggs / Sunset (2024), poet Craig Jun Li’s narrative fragments), or Juliette Desorgues’s reading series presenting artist-writers at the legendary, women-run, and all-red bar Le Scott. (The moment when Shola von Reinhold ripped up her text and sang karaoke instead really slapped.)

View of “Twin Flame,” curated by Liza Lacroix and Philipp Farra, Le Bailly, Paris, 2025. Photo: Liza Lacroix

A reading series curated by Juliette Desorgues at Le Scott, Paris, as part of “Mono Mania,” 2025. Photo: Juliette Desorgues

Or, slappier still: Ryan Foerster’s box. Over the summer, the Canadian artist got access to one of the 475-year-old bouquiniste stands along the banks of the Seine. He was open every day during the fairs, gathering people together around scavenged assemblages, new editions of his du späti review, zippers, trash. At the launch of Turpentine, a long-running zine by artists Jonathan Martin, Jean-Luc Blanc, and Mimosa Echard, really feeling like Tefal pan on the last day of the fair, I wondered: Why do Foerster’s scattered absurdities feel kind of new?

Alex Quicho, in Spike’s latest issue, “Nostalgia,” describes newness as like “being thrown through a car windshield and waking up dizzy in a dew dropped field.” The week of Art Basel Paris gave me no smashed windshield, no dizziness, no field. But projects like Foerster’s box, or off-spaces where people, very carefully, put weird shit in a room, seems to me like the culturally “useless” dew necessary to remedy, at least aesthetically, the rationalized mood-board logic of an increasingly corporatized (art) world. All those New Men. This is my wish as a fair-frazzled crêpe pan: more dew to wet our brains.

Ryan Foerster’s bouquiniste along the Seine, 2025. Courtesy: the artist

![Jo Spence, The Final Project [Specimen Jars], 1991–92](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/syotmk9q/production/bd6774f5566fbb2199b0fc6cbb58fee47cd91359-2000x1603.jpg?w=3840&q=70&fit=clip&auto=format)