Deborah Hazler brought anger on stage. In That Rant and Rave – performed at ImPulsTanz , Europe’s biggest dance festival, originally premiered at brut Wien in 2020 – the Vienna-based dancer and choreographer wears a costume with bulging muscles, as if under protein overdose, to explore anger from an existential and political point of view, but also its relationship to comedy.

Astrid Kaminski: You can be soft, silent, and inefficient, but for That Rant and Rave, you decided to be loud and rough. Was there a specific moment when you felt that you needed to hiss and roar?

Deborah Hazler: This moment has been building up for years. There is something inherently angry in me, and most of my previous pieces were conceived because I found something troubling or frustrating (the constant objectification of the female body, for instance, or the idea that if you work hard enough, you can be whatever you want). I even named my organisation Angry Agnes Productions because I get so upset looking at our society, at how people are behaving towards one another. I also get angry at myself a lot, because I feel I do not speak up enough when I see injustice, or because I catch myself being judgmental about someone or something that’s none of my business.

Deborah Hazler, That Rant and Rave , 2020. Photo: Franzi Kreis

At some point I had this desire to make a piece about all the things that piss me off. I wanted to overcome my fear of publicly expressing anger. This is a big point, because being angry is not necessarily seen as positive, and I just gave myself the freedom to let everything out – from the rage I feel anytime our chancellor opens his mouth to explain why we can’t take in minor migrants even though it should be our responsibility as human beings to make sure that everyone can live in a safe environment, to how helpless and furious I feel when I go skinny dipping and encounter a man with an erect penis standing next to me. Next to some of these heavier topics, I also give space in the performance to some that are less existential, like the overuse of the word authentic, or why the person I had a date with didn’t even wash their hair, or why people keep sending me pictures and videos of cats. It was important that while being serious, there was also room for humour.

AK: Compared to rant experts like performance artist Ann Liv Young, you don’t seem very dangerous. You don’t poop on stage, you don’t heckle people personally – only some rather impersonal Publikumsbeschimpfung. Are you afraid of insulting?

DH: While I hope to make performances that might challenge people’s way of thinking, attacking and insulting is not my mode of being, onstage or off. There is a difference between being angry about injustice and name-calling or bullying, and as someone who was bullied growing up, I don’t think I can gain anything from deliberately hurting someone’s feelings. Still, I wanted to challenge myself with how I address an audience, without my usual mode of people-pleasing.

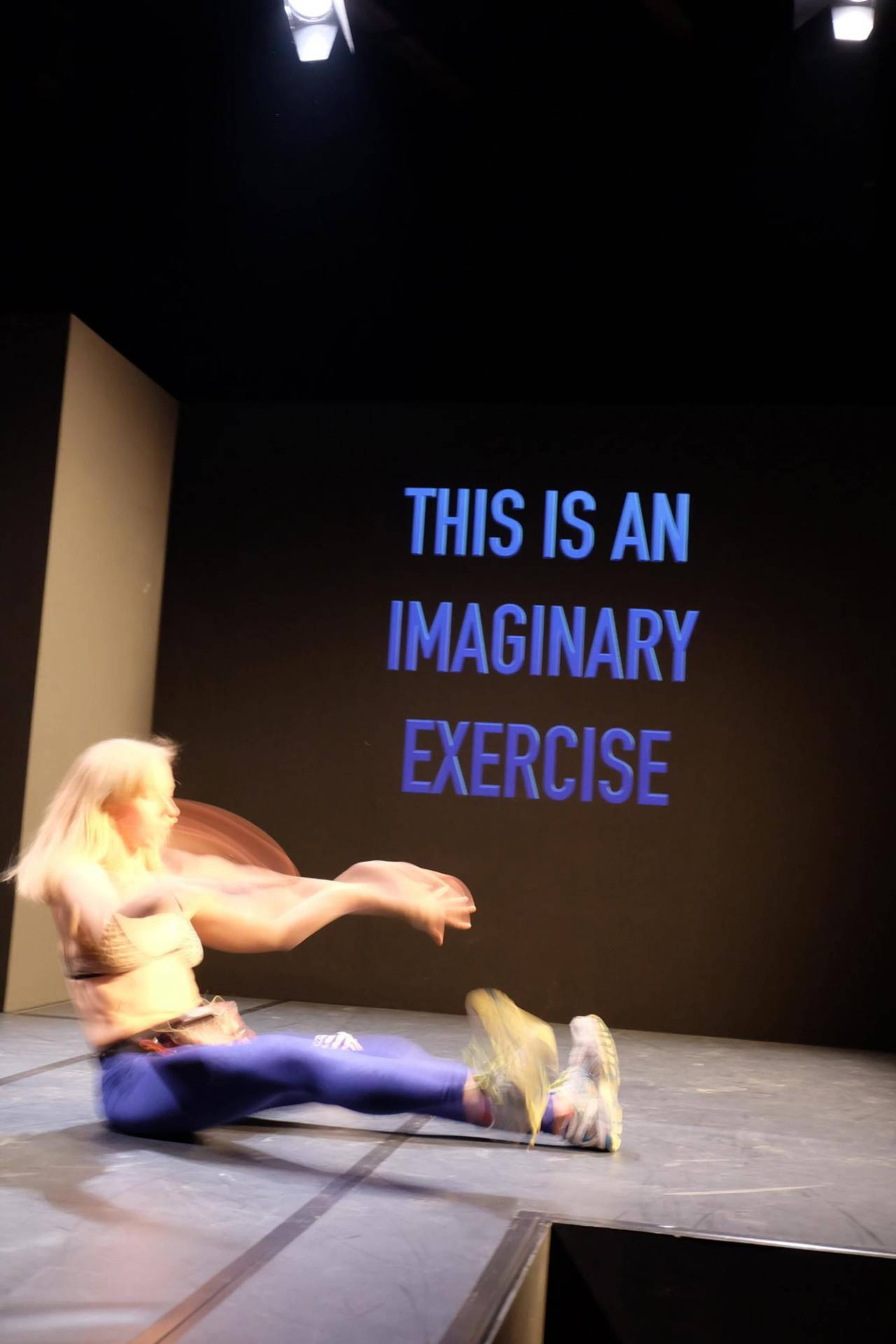

Deborah Hazler performance. Courtesy: the artist

AK: You wear a costume with bulging muscles, as if you’ve eaten too much protein, and there’s a huge foam sculpture on stage like a fancy monster from an animated film. The props seem to underscore your method of processing content through form. Or are they rather mascots that keep you from getting lost in the aesthetics of political satire or cabaret?

DH: I can’t explain the choice of costume and props analytically. They were conceived somewhat intuitively in the rehearsal process. Originally, the piece was supposed to be a duet, but the other artist, Nora Jacobs, was ultimately not able to participate because she got pregnant. Since I couldn’t simply replace her, I decided to have something else on stage with me that I could interact with, some other kind of counter-player, and asked the artist Dorothea Trappel to develop something for me. The text for the performance was already there, so we had to create something that could support it and give the image of ranting and raving more depth. I had this desire to become a monstrous woman.

Men have the right to criticize because they take that right, meanwhile, women and non-binary people are seen as “just complaining”

Both the costume designer, Otto Krause, and Dorothea found it important to create something that works with the text and not against it and in both cases, we ended up using foam as the material. The costume might look very lightweight, but it is actually extremely heavy and restrictive, making it difficult to move. We thought that these imposed physical restrictions were fitting, given the subject. I also worked with Anna Mendelssohn to develop the vocal component of the performance. I come from movement, and she helped me find different textures in my voice, while my dramaturgical advisor Milan Loviška helped me explore different physical formulations of anger, mostly through my interactions with objects. The gestures can create tension, either supporting or undermining what I’m saying. They provide a good way to struggle – not only a representationally, but also literally, a real struggle.

Behind the scenes of That Rant and Rave , 2020. Courtesy: the artist

AK: The political scientist Nikita Darwan gave a talk on criticism last year, where she said that “from a post-colonial, queer-feminist perspective … criticism does not necessarily lead to emancipation. The imperative to be critical can also be compulsive and violent, not just counter-hegemonic and progressive”. In other words: maybe aggression as the default mode of critique is over, just another form of privilege?

DH: I guess there is some truth in that. Criticality can be constraining, so I often ask myself: how can I be critical and still stay open? We can also look at anger from different angles. In preparation for That Rant and Rave, I read books by feminist theorists Sara Ahmed and Soraya Chemaly. They talk a lot about how women, and especially women of colour, are always seen as aggressors when they open their mouths to point out the injustices that they are constantly subject to. They automatically get stigmatized, whereas men are taken more seriously when expressing their anger. Men have the right to criticize because they take that right, meanwhile, women and non-binary people are seen as “just complaining” or are even labelled as hysterical. Maybe anger is not the only – or even the best – tool to enable change, but suppressing anger is also counterproductive. There is no right and no wrong in this; it’s more a question of the individual ways in which we can engage in this world.

Deborah Hazler rehearsing That Rant and Rave , 2020. Courtesy: the artist

AK: It’s like the Weimar-era journalist Kurt Tucholsky said: the satirist is a wounded idealist.

DH: In my study of humour, I once read a book called Comedy is a Man in Trouble. I think that the man in question is one that is always a little wounded, a little melancholic. This is how I see myself, too – fairly melancholic. I feel there are many instances where we could care more for each other.

AK: You co-created a platform for mutual support and care in Vienna, called RAW MATTERS, where artists can workshop pieces in progress. Seems like this was your idealistic self coming through?

DH: If we are lucky as performance artists, we get to present our work in front of an audience. This encounter reveals a lot about the piece that, until then, often stays on a conceptual level. In a typical setting, the audience is not consciously imagining the whole process that an artist has to go through leading up to the presentation of a work. I personally go through lots of ups and downs, questioning myself and interrogating what I want to exchange with the world, while I’m developing new work. If nobody follows this process, it can be such an alienating experience. So, with RAW MATTERS, we try to create a space where it’s not so lonely, where artists are invited to show their unfinished processes to better understand if their intentions are received by an audience (or not), and then to continue working on their pieces based on this experience.

Deborah Hazler performance. Courtesy: the artist. Photo: Michel Nahabedian

AK: Recently, you’ve also taken up knitting and textile art. How does this relate to the logic and perspective of your performing work?

DH: I always enjoyed knitting and doing crafts. A few years ago, in Chile, I started weaving, and I decided I want to continue exploring the world of textiles. I think that my fascination comes from the rhythm of those disciplines. Often, they take a long, long time – it’s a long process, from having an initial idea to finishing the piece. At the moment, I am, for example, hand-stitching a quilt. I have been working on the blanket for at least two months now and am nowhere close to finished. The time-based qualities feel, in a way, very similar to performance.

AK: So it’s like – textile as a way to make temporality visible, including form and improvisation?

DH: Yes, there is this sense of creating a record, of having something that stays. On the other hand, this also makes me question: is posterity necessary in the first place? Is it necessary to make things that stay?

___

DEBORAH HAZLER is a Viennese performer and choreographer. In 2010, she founded the non-profit organisation RAW MATTERS with Nanina Kotlowski.