Tongo Eisen-Martin is today’s leading revolutionary poet. His unflinchingly militant and aesthetically bracing poetry has continued to evolve from his debut, Someone’s Dead Already (2015), through the 2018 American Book Award winner Heaven is All Goodbyes and Blood on the Fog (2021). Eisen-Martin doesn’t just write about activist matters; he’s worked for years to further political education in jails and prisons and throughout the communities of the Bay Area. He taught at Columbia University’s Institute for Research in African American Studies, where he designed the curriculum We Charge Genocide Again!, addressing the historic violence American white supremacy has imposed on Black communities.

David Brazil: You’re the poet laureate of San Francisco, which is your hometown, and a lot of your poetry is about the city. You’ve written: “Turns out not enough of San Francisco was there in the first place.” What can you say about San Francisco now?

Tongo Eisen-Martin: What’s interesting about San Francisco is that it doesn’t have the biggest population, but it is very densely populated. And so, if you walk a mile or walk a half a mile in any direction, it can feel like you’re in a completely different and singular world. Because I think what San Francisco can boast is that even, like, no two houses are the same back-to-back in San Francisco. It has a diverse topography. This also had an effect on my consciousness. This small, compact city actually gives you a sense of belonging to several bigger pictures.

Growing up in San Francisco, especially with the people I was raised by, was a study in imagination made praxis. You had very creative people of revolutionary commitment, putting together enough of the universe or enough of the institutional matrix (the alternative people structures), so that youngsters like me could build a political or even psychic immune system that would be necessary to repel the rest of the San Francisco project, which has always been imperialist — as well as what would serve not just political outlook in the future, but my commitment to humanism or humanization, both of myself and others, or understanding that the humanization of others is the only thing that humanizes me.

Whether it was Meadows Livingstone, which is a little freedom school I went to, or whether it’s being trained at the Larkin Dojo, which used to train Black Panthers and other revolutionaries, or going to the Western Edition Cultural Center, which is now known as the African American Arts and Culture Complex — these people and what they put together gave me a disposition of imagination to emulate. One that is hell-bent on determining reality for us.

And though our revolutionary movements in many ways lost their epoch of struggle, the veterans of those movements were still around, and were still doing mass work, just not from within the framework of their past organizations. There is a continuity there — not as potent as if the organizations themselves have survived their war with the system. But definitely a lineage was passed down.

At the same time, San Francisco traumatized me. Police let me know early that not only was I not a human being in their eyes, I was the enemy of humanity. To treat kids like they’re an embodiment of evil that you have to overkill — I think that’s what’s interesting about police terror here. And communal conflicts were also part of my thematic universe. San Francisco, culturally, is a scrappy place. We never wanted to leave it to Beaver here.

Entrance to Rikers Island, New York

DB: When you lived in New York, you taught at the prison Rikers Island. Can you speak on that?

TEM: I don’t even know where to start, because there was a point in my life where teaching in jail was what I did. It was central to me — just like someone is a poet or someone is a musician, I was a jail teacher, because I believed that’s where the revolutionary work was. That’s where you really politicize people. This is where you really move in the trenches of the principal contradictions.

So, you couple that with a youthful energy — I was fully immersed in that potential. And the thing about jail is it’s an interesting parallel universe of a dictatorship of the proletariat. In essence, it’s a liquefied proletariat. A surplus population in order to destabilize what was becoming more and more radical Black labor, and radical Black people whose movements were gaining more and more of a mass character because they were capturing more and more of a mass imagination.

There was a culture to it that you could take advantage of, and there is kind of a justice of reputation and practice. So, people see you coming in there and you’re not full of it, and they see people respond to you – I worked with a lot of people. It was an immature time for me, in that I thought you could actually make a revolutionary contribution without being part of a revolutionary organization. And there’s all kind of problematic byproducts of that. But it was the first thing I ever was – even though I had poems the whole time. I started writing poems the summer before I got to school.

DB: Why was there such a gap between starting to write as a teenager and then publishing your first book in your thirties?

TEM: I didn’t take it as a central identity, man. It was like a central identity I had to grow into. It took a long time for me just to even call myself a poet.

DB: How can art contribute to the struggle for Black liberation now?

TEM: I think if we know anything at this point when it comes to revolutionary movement, it’s that consciousness is not everything, but without it, you have nothing. You can have both a commitment to action and a mastery of action. But if you’re not building the consciousness of masses along the way, you don’t have a movement that is invincible to systemic coercion, corruption, and absorption.

Art is really just a conversation starter.

And that’s where art is crucial and beautiful, because it’s begging you to build your mind on top of it, it’s begging you to interact with it. Art is a request just as much as it is an assertion. It’s really just a conversation starter — the highest form of conversation starting. And that’s what’s crucial to any revolutionary development. You can’t just have revolutionary thought deposited in your mind. It almost betrays the true nature of revolutionary thought to call it that. It’s a revolutionary process of inquiring. “Revolutionary thoughts” are just the temporary conclusions you come to along the way as you continue through this living process of humanizing yourself and humanizing the society. Art keeps a revolution honest because it’s just perpetual commentary.

Before revolutionary movement is facilitated by organization, art is crucial in helping people build their consciousness to a point that requires revolutionary organization. Once a revolutionary movement has entered the stage where it’s facilitated by these revolutionary organizations, art is crucial in dialoguing with these organizations and with the reality that these organizations have created.

Also, art is just the activities of your body and your mind outside of shorthand social convention. So, if I don’t have to talk to you in order to socially reproduce myself and I can talk just to talk, poetry is going to come out. You know what I mean? If I can move, not for the sake of producing something, but just move — some dancing is going to happen, right? It’s a crucial part of the synthesis of the human journey to have those powers that exist beyond survival. And it’s just crucial to the revolutionary process.

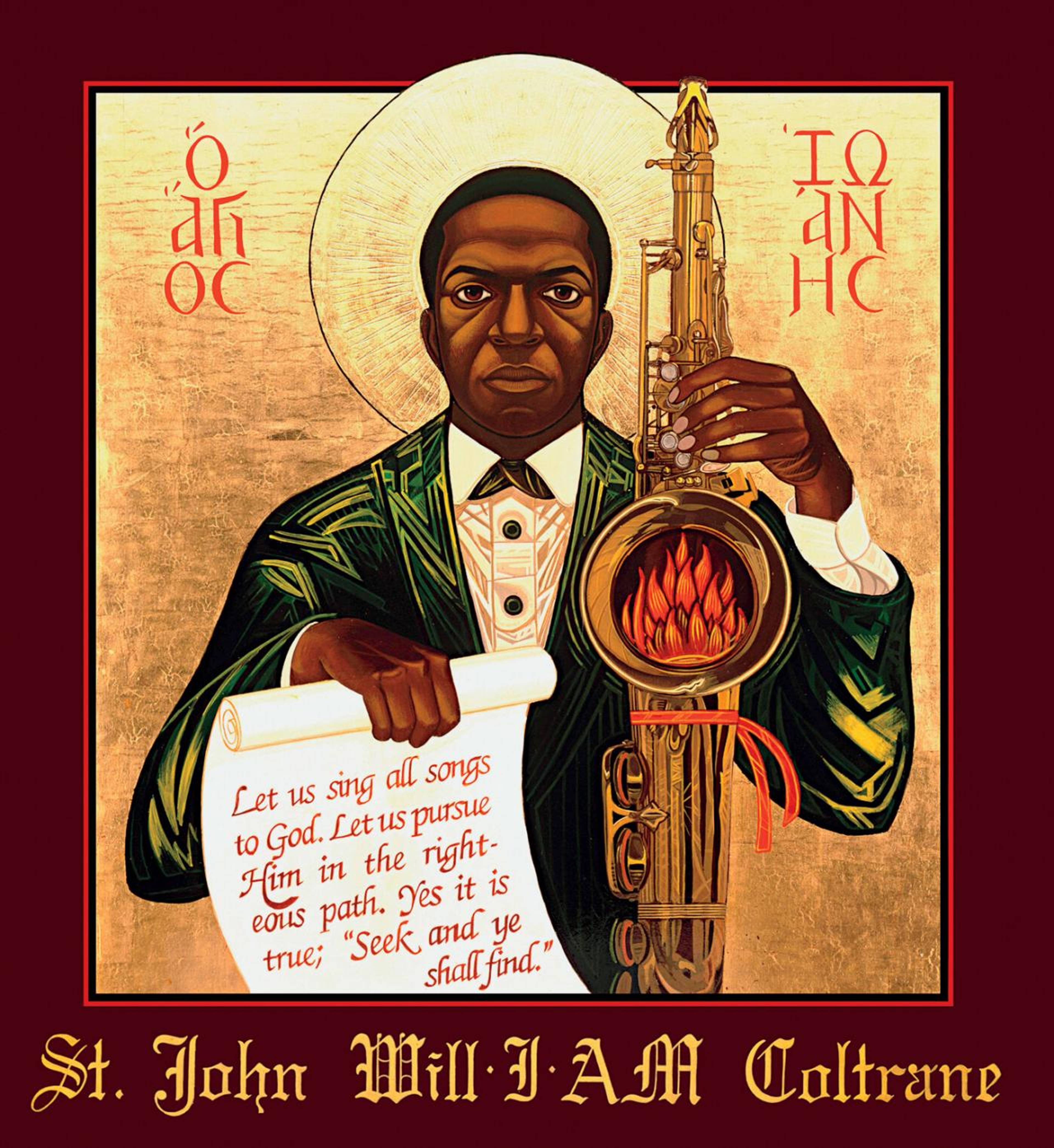

Deacon Mark Dukes A.O.C, Coltrane icon at St. John Coltrane African Orthodox Church, San Francisco, 1991.

DB: I remember asking you years ago about your influences, and you said: Audre Lorde and Roque Dalton. And that was it. Are there other folks who are on your mind lately — precursors, ancestors?

TEM: Since we had that conversation, probably the deepest meditation I’ve gone on is with Coltrane — both his music and his words, those slices of philosophy that were captured in interviews along the way. What’s groovy about these kinds of legends is just to think about what is making them tick can be very educational. Even if you get it wrong, trying to figure out how Coltrane is getting through this solo, or what guides he is bouncing off, can be instructive. But actually, a lot of the book of was written in that energy field.

DB: What does his work mean to you?

TEM: I don’t even know where to start, man. I asked Sonia Sanchez to give me an autopsy of those times — that kind of monsoon of a moment in Black art and Black resistance. And the first thing she said — we had two leaders in all of the potentials of the human psyche since. We had Malcolm X, and we had John Coltrane.

Those cats heralded our potential and were the compass for us to internalize. It’s almost like a gathering of prophets. I think Coltrane’s craft makes itself available to any generation. Here is almost like the equation for evolution — just a humble and curious mind that is always seeking to get a little bit more insight out of exactly where it is.

The interesting thing that Coltrane said about his soloing — he said, I rarely see it in its entirety. I rarely have a complete picture of what I’m doing. I really deal with the location of where I am. And the same rules apply to the poem. To really push your potentials for language, you have to get down into that one image, you have to get down into that one line and, really, anything might happen next.

For a poem to be a steppingstone to a higher consciousness – fragile, faint, maybe not even possible, but just the idea that it’s there, and always keeping an ear out for it – is a Coltrane instruction.

It’s like the possibility of a divine voice. It’s almost an impossible proposition. But the idea that this harmony or this note might actually be the language of heaven, or that this is the actual language of the universe — that pursuit. But it’s almost like looking for a star in the sky, just having your mind looking for that potential, that you could write a line that just gives a little hint of a much bigger energy facilitating itself, or really speak the language of unity, or really use the structures of unity in a block of words. For a poem to be a steppingstone to a higher consciousness — fragile, faint, maybe not even possible, but just the idea that it’s there, and always keeping an ear out for it — is a Coltrane instruction.

What’s beautiful about the Coltrane instruction is spiritual pursuit without religious ambition, or without the desire to participate in religious political economy. It’s a pure pursuit of doing right by divine instruction and doing right by human beings and their consciousness — but with no quest to recruit numbers of followers, no building — just really taking it one fucking note at a time.

I think that’s one of the tricks, to bring it back to the potential within a poem — you can pull off all these co-emerging facets of relating to reality if your intention is to learn something yourself. Because when you do that, it’s almost like the trick is to listen to the poem just as much as you’re creating it. And based on these few threads that you come up with, these scraps of thought that have a ring to them, you can build out a person of a poem, whose only purpose is the request for more insight.

Because righteous inquiry is ultimately the thread that runs through the entire poem and really is the only thing that makes sense, because it’s also the best way to tie your day together. What am I learning as I go through? If the spiritual part of your day is oriented towards your ego, you’re messing up. If the political movement part of your day is oriented towards a weird emotional vendetta or past insecurity you’re rebelling against, you might be a highly effective organizer, but you’re out of step with evolution. The personal part of your day can be oriented just around doing the right thing — like altruistic duty. All these things can be true, but it will actually divide your psyche up as a human being. But now, if you travel through these different facets only with the intention of learning something — well, now there is a unity. There are threads; connections become available, and one starts helping the other.

___