It’s strange that musicians would release two albums under one name; stranger, even, that they’d call it HOAX (2024), fog-machining doubt as prelude to the music; strangest yet that one of those albums would be, not a riff on or a reflection of the other, but its negative. Strange, though, is something of an Amnesia Scanner calling card. From debuting with a live-concert mixtape of grime, trap, and rave, through collaborations with artist Jaakko Pallasvuo (on the audio play Angels Rig Hook, 2015) and Harm van den Dorpel and Bill Kouligas (on the performance-turned-record Lexachast, 2015-19), and into studio albums like 2020’s Tearless, Ville Haimala and Martti Kalliala’s Berlin-ish outfit has often put the elative structures of pop and club music into a blender and glassed out the odd foam on top. Hooks cut short; animatronic vocals elude sing-a-long; beats wander off in other pursuits, apparently eagerer for the buggy, laggy comedown than the harmony of the high. (A tell, maybe, that their most-played song on Spotify to date, “AS Too Wrong,” turns on the line “Who cares if I don't fit into the k-hole?”) The palette in their end-of-server worlds is sunsets and neons, but beamed through an atmosphere frottaged with smog and an antiseptic, never-off highrise glow.

Even by those benchmarks, though, HOAX, their second full-length collaboration (following the album STROBE.RIP) with the nonpareil A/V hacker Freeka Tet – a creative mercenary whose own credits include productions with the likes of Aphex Twin and Oneohtrix Point Never – marks a hard left turn. Its first half, AS HOAX, is a plasma of grunge by way of hardstyle. It’s skittering and anthemic, wistful and screamo, a cut-out ransom note of forfeiture and refusal postmarked to the too-smooth present. The obelisk of noise that is its second part, FT HOAX, offers that demand’s strange fulfillment. Cued by the phase-inversion technology that make the sounds in bluetooth headphones really pop, this debut record from Freeka Tet is functionally the AS take in inverse: Track by track, a noise-cancelling script reveals the rhythms and tones grained into its interior, turning onto the surface of sound the lining of its subconscious. It amounts to a collision of matter and anti-matter, the energy burst of holding present both parts of a contradiction – extremity gesturing towards serenity, drone-ification as a decryption of subtlety, emotion as pre-fab experience.

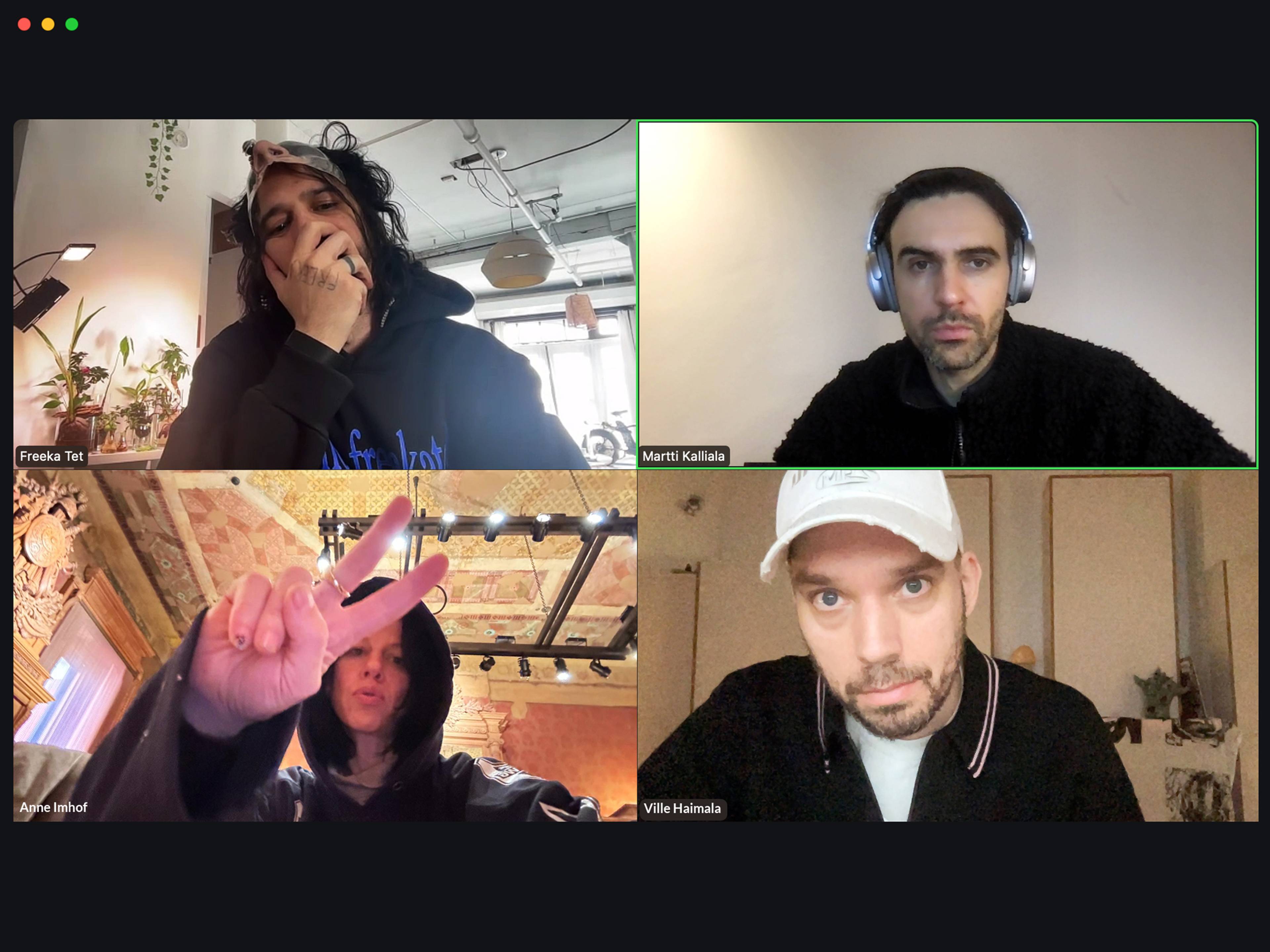

The following conversation with artist Anne Imhof, who has worked with Haimala on the scores for her performance-installations “SEX” (Tate Modern, 2019), “Natures Mortes” (Palais de Tokyo, 2021), “YOUTH” (Stedelijk, 2022), and “Wish You Were Gay” (Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2024), took place via an appropriately glitched-out Zoom call.

Screenshot of a Zoom call with Freeka Tet, Martti Kalliala, Ville Haimala, and Anne Imhof, December 2024 (from upper left)

Anne Imhof: When did little Freeka, little Martti, and little Ville first encounter themselves as musicians?

Ville Haimala: I had a punk band with my classmates when I was thirteen called Hangover.

AI: What did you do?

VH: I sang, and played guitar a little bit as well.

Martti Kalliala: I had a little rap project with my classmates when I was, like, eleven, but –

AI: Who wrote the lyrics?

MK: I did. For context, it was this era where these novelty rap groups were popular in Finland. As an adult, I was part of these different music scenes – rave, techno, disco, whatever was DJ-led – for a long time, but I never made music myself. It was only when I met Ville, actually, that we started to organize this club night together, which eventually led to us making music. But I still wouldn’t dare refer to myself as a musician. More as a producer, or something along those lines.

Freeka Tet: I didn’t grow up with music at all. Like, I had no album I was listening to, no real taste or anything. I was forced to play clarinet as a kid, which was awful. I remember walking in the music school and seeing kids playing drums, and I was with my clarinet – full-on shame.

When I was around sixteen, I had some friends who played metal. The singer dropped out of one of these bands, and they were, like, do you wanna sing in this thing? I had no idea what I was doing, and I wouldn’t say it was music – it was just some kind of weird feeling. I started to do stuff with software, electronics in my twenties. But, same as Martti, I don’t consider myself a musician. I’m just experimenting around.

We always look at words as images as much as language, and I think HOAX is just a very cool-looking, beautiful word. (Ville Haimala)

AI: Let’s jump to your new album, HOAX. It’s not a double record, but two records with one name, which the album notes describe as two “mirroring, mutually-reinforcing (or perhaps deconstructing) records.” Can you talk a bit about this?

MK: Maybe I can start with a funny anecdote. Initially, the album was supposed to be called PSYCHO.CHAT, like psycho-dot-chat, following the same logic as our previous album, STROBE.RIP. Both would be URLs, with websites as extensions of the albums. We were working around this title for a long time, but I forgot to buy the domain, and someone else snatched it. I offered him a pretty big amount of money, but he refused to sell.

VH: In the moment, it was a big deal that this whole work had to be called something else. But HOAX feels very natural now. We always look at words as images as much as language, and I think HOAX is just a very cool-looking, beautiful word. It also goes with the lore about this big project we had in 2021 called scammer.market, where we opened all our unreleased productions as a sample pack. Every musical phrase had its own name and its own origin story, but no copyright, and everyone could use them for free. We’re always playing with identity, with the issue of whose voice this is, with the kind of —

MK: Truth.

VH: Truth. So, I think HOAX aligns pretty well with that.

MK: Really, since the beginning of Amnesia, there’s always been a very ambiguous relationship with the truth in our work.

VH: I think in Freeka’s as well, no?

MK: Exactly.

FT: You guys give way more attention to words than I do. Even sonically, I haven’t written for any of the albums we’ve done together – not a single lyric. My part is more feral – just a sound or scream.

AI: Freeka, your contribution to the record seems pretty abstract.

FT: It is.

AI: Can you describe the two respective covers?

VH: We got inspired by a lot of photos of people selling their records on eBay or whatever. There’s this classic genre of people taking a photo of a Dr. Dre album or something like that, where the seller themself is accidentally reflected back from the glossy cover. We wanted to do something similar, to make an object that would reflect our listeners. You can see different reflections of Freeka, Martti, and myself we fed into all the different streaming services.

Left: FT HOAX, vinyl sleeve; right: AS HOAX, vinyl sleeve. Courtesy: PAN

FT: The object doesn’t exist without the buyer somehow. And maybe the buyer even becomes the object.

AI: It’s very inclusive of your fans, of their images, in a beautiful way.

VH: The project is not so personality-driven; it’s never been about our faces. We’ve used this kind of input from our fans, our friends, whoever as visual material before. When people post from our shows or take pictures wearing our shirts, we’re very eager to throw it back to the system; PWR Studio, who create a lot of our graphics, actually build up their AS image bank by mining people’s feeds for material. It’s a sort of feedback loop.

MK: The magenta color of the AS cover somehow came naturally. For a while, though, we were thinking, what’s Freeka’s album, considering what it is? How could the cover image be canceled? One natural idea was to just take the color opposite of magenta, but that turned out to be brat-green. So, we went with zeroing out the color entirely.

AI: I would have taken black, too. AS is self-branded as an “experience design studio.” Maybe that was before Freeka joined the project, but there’s something of that in how you describe thinking about images, but also the music – there’s almost something applied about it, you know? Like you have the use of the thing in mind. Is there something that you feel like you’re applying to your fans?

VH: “Experience designer” is a term we use in a tongue-in-cheek way. At the same time, experience is definitely the lens we’ve thought about a lot of the project through, both musically and especially with the live show. We think about the effect more than the affect, I guess. There can be very emotional moments in songs or our sets, but it’s more like charging different sorts of waves of impact towards the audience and inviting them to take what they will from it; we’re not didactically telling a story.

In this sense, long before we met you, Anne, we were admiring your work for the fact that it has this similar first-person-gamer angle onto experience, where you step into a world of sorts and frame it yourself.

Anne Imhof, ANGST II, 2016. Performance view, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin. Courtesy: the artist

MK: Before we ever even played live shows, this was always a shared imagination of how this very online music thing would come alive in a space or IRL.

Was ANGST [II, 2016] the performance of yours at Hamburger Bahnhof? I remember being there and thinking, yeah, this is exactly it. You somehow really captured something we also wanted to achieve with the live presentation and experience of our work.

AI: HOAX feels like one step further into the collaborative and technological world that your live shows have created, but this time, with you guys cancelling each other out in a sense. Do you consider it a concept album?

VH: No, it’s in the continuum of work we started together. STROBE.RIP was a traditional collaborative record, where all the music was made together and released together. With HOAX, we worked together in the moments when it felt right: There are some songs we recorded together with Freeka, but there are others on the AS side where he wasn’t involved at all, and effectively two different HOAXes came out of that more developed process. But when we push these two things into the world, with a website and live shows and everything else, then that becomes, as you said, the world of HOAX.

AI: So, it’s a new form of collaboration?

FT: When we started with STROBE.RIP, we basically tried to merge everything, which made an album that went all over the place; there was less time where everything was tight. Afterwards, we started to work on a mixtape from some of the leftover songs. But the thing is, sometimes, AS’s writing goes a little too fast for me. I was on tour with another project, and during that time, probably sixty percent of the mixtape changed. I was feeling like I didn’t have too much to do with it.

I see AS as, we’re collaborating, but it’s also, for me personally, a good platform to do new things and experiment. It was cool to try to mix everything together, but sometimes it’s better to keep things a bit separated. With HOAX, we could understand who was doing what, who was the songwriter, who was writing music, who was more on the conceptual aspect, and so on.

AI: I was at an AS concert in LA where kids were moshing, like at a metal concert. It was really Wall of Sound style, which I can imagine again with AS HOAX. But the FT album sounds like a sound-shower environment: You want to really dive into it, but you will never perform that stuff in the same way. Were these two albums thought out towards different audiences?

FT: I don’t know if they were, actually. Because in terms of, like, ideology, they’re ultimately very similar. We are also starting to integrate the noise-cancellation into the live show with a system I designed.

VH: We were just testing it for the first time in Mexico City, and it’s so crazy. We can go from Freeka’s to ours instantly – blam!

The live show also winds up creating a third version of every song. It’s where this project really lives. It’s funny too because, even though you would think Freeka’s version is very mellow, when you expose it to a big sound system, it’s actually way more intense than the AS version. It’s not white noise; there are so many frequencies, it’s this kind of wall of harmonic noise.

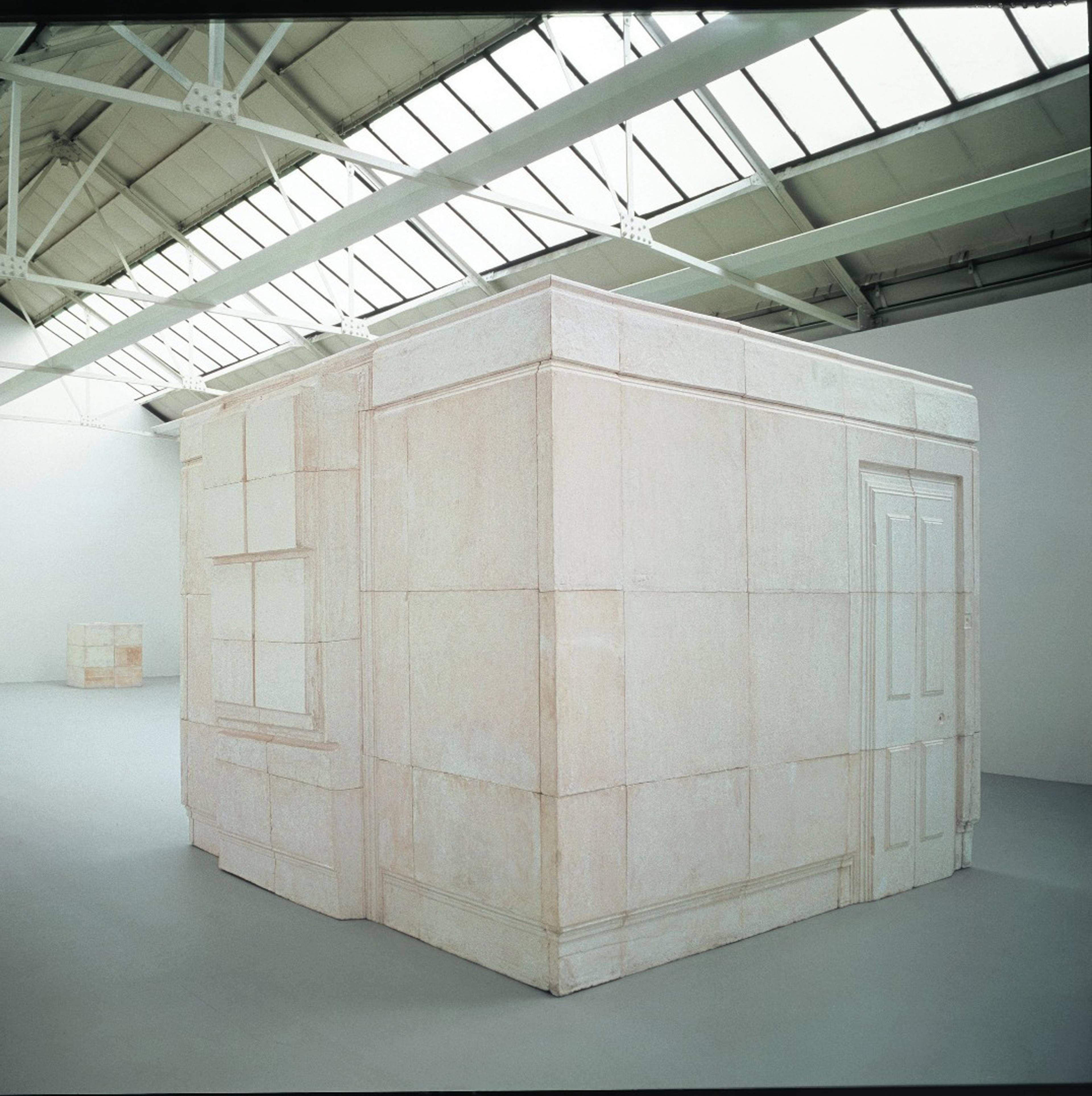

FT: I don’t know if it’s the best reference, but Rachel Whiteread did this amazing piece called Ghost [1990]. She went to this house in London that was going to be destroyed and filled the entire place with cement. When the house was torn down, the giant concrete blocks created —

AI: It's the negative.

Rachel Whiteread, Ghost, 1990, plaster on steel frame, 269 x 355.5 x 317.5 cm. Courtesy: the artist and National Gallery of Art, London

FT: Yeah. Like a negative, the imprint of the empty space. Technically, that’s kind of what’s happening with the noise-cancelling live system. You can recover everything that’s missing. In Rachel’s work, there were all these previously unseeable details that came up in the negative space – you could see in a print of a lightswitch how it was scratched and so on.

The live system works as a simple crossfader going from the original song to the noise-cancelled conversion. When we started to apply the noise cancellation, we found that in the middle of the transition, there’s this sweet spot right between the two things. New things are showing up that we don’t really hear normally, like these full-spectrum frequencies that keep the rhythmic feel of the original song.

VH: Yeah. It’s almost like a subconscious of the music. There are colors popping out that we never knew existed there.

AI: Lately you’ve also been using voice on stage, which is a new thing for you, right?

VH: Yes! Since very early on, we’ve had this disembodied voice made from different vocal hooks and voices. It’s this weird Frankenstein voice, which is not a normal human recording and doesn’t belong to anyone, that became iconic to the project. But then we didn’t really know how to embody it on stage, which was always a bit awkward, to perform and not be able to do this voice.

Ever since we worked together, Freeka has built several bodyfications of the voice specifically for us. The first was called Anesthesia Scammer, which was an animatronic mouth that “sang” the vocals at our 2019 performance at Kraftwerk in Berlin. Now, he has created a system where we can wear this avatar of a voice onstage and finally do it live. Freeka does it together with me, even though the vocals aren’t originally recorded by him. To be able to finally use that energy of performing live, of holding a microphone and screaming to it, and then out comes this very bespoke, very designed voice, feels like magic.

AI: For me, the aspect of the singer or of the voice is what brings the most emotion to live performance. Within your music practices, though, the ego is almost taken out as an emotional factor – there’s no idol, in a way.

FT: We made a video for the song “LEDGE” where we’re eating pasta. There is a little wink to it where we made a really tiny version of the original Oracle animatronics, and there’s one shot where I actually eat it – like, I swallow it. To me, jumping into this project that already existed, it captures this feeling that, when I’m performing, I’m just a host for this thing to materialize. Unless I’m screaming, which is really me.

VH: I think it would be very cool, in the future, to bring more vocalists to sing with it, or even to bring people from the audience to sing with it. Because it’s such a weird experience to sing with a voice that’s not your own.

MK: When we started AS ten years ago, it was all quasi-anonymous. For our first live show, we even hired these kids to stand on stage. We were very inspired by these big hardstyle festivals like Mysteryland or Defqon.1 where, at the “endshow” that closes the weekend, there’s no DJ, there’s no act – it’s literally the stage that’s performing. We were really interested in the idea of removing ourselves from the center of the live experience. But practically, it is quite difficult for an audience not to be able to relate to a human or some kind of avatar, in particular when vocals became a bigger part of the project. So, Freeka’s system is also a great technical solution to this dilemma we’ve always had.

AI: You are basically giving the avatar role back to your audience. To me, it’s almost like you’re filling the idol figure with their own image – how you place the voice makes it a very democratic platform, let’s say.

VH: The nature of this beast is that it’s always been many-headed. It has many voices: sometimes 1,000 at once, and sometimes just one very weak, fragile voice. It’s evolving all the time, and it feels like, finally, we’re able to transfer that energy into the body.

FT: What I like about AS is that it was always this experimental project, but with a big look into pop culture. To me, the way the voice process works in live performance is very similar: When I first thought of this system, the idea was to do a sort of karaoke system on steroids. You could auto-tune if you want to be more into the melody by turning a volume knob to level two, or really crank into overdrive mode and actually be the voice of the original singer. When we perform an iconic song that everyone knows, it feels like pushing the pop part of the project in a way that now feels very hyperpop. Are we performing, or are we just doing karaoke?

AI: You’re taking your own song to karaoke. That’s actually pretty cool.

VH: Like singing along to your own song onstage. I like that.

AI: Say you’re in a taxi and you tell the driver you’re on the way to your gig and they ask what kind of music you make – how do you describe it? And you can’t use the words “computer” or “different.”

VH: Noise.

FT: I feel the answer would change depending on who you’re talking to, if it’s a more average person versus someone who is really into avant-garde experimental music. And I feel like the fact we have to adapt to describe it is pretty much its own description of what we’re doing.

VH: If you go through our catalog, it’s a lot of different kinds of music. There are written melodies that have some relation to each other, but it’s much more about, like, a texture or some sort of grain.

MK: It’s a bit like the iceberg meme: The surface-level, taxi-driver version is electronic music. But, besides its being a lot of different music, all of the output has kind of evolved and layered onto itself, in terms of complexity and context and reference. It has thrived on adding, rather than shedding these layers to reinvent itself.

Using AI in the creative field is so divisive – lots of people think it’s just shit to work with it at all and are reticent to the technology. (Freeka Tet)

VH: What would you say if someone asked you what kind of art you do, Anne?

AI: I make something like rock concerts in museums. But then they ask me, “Are you the singer?” – that’s a difficult question to answer.

MK: I mean, in a way, we do that as well.

AI: I met Freeka two days before the release of the video for “OVER.” The song has this lyric, “We’re so back, we’re so over,” which I think is genius: It’s a way of both presenting yourself and of hinting at this dystopian way of ideas canceling each other out. He came out of the studio – where he’d been recording with Arca – and sat me down at the table and he said “Look at this! How do you like it?” and showed me the video. I have to say that the video, which was completely generated with the AI tool Edge, created this amazing feeling that other images produced by AI simply don’t.

FT: The video had nothing to do with the song at first. I just wanted to make a horror movie with plastic bags. But listening to the song and the lyrics, I thought it would be interesting to start with a fake narrative about recycling and climate change (the “It's So Over / We’re So Back” meme looks like a recycling logo), and then turn the story into something totally different (fear and acceptance of new technologies).

This was the first project I’d ever made where it was obvious to me how most of the audience would react to it, because using AI in the creative field is so divisive – lots of people think it’s just shit to work with it at all and are reticent to the technology. This is where the hidden narrative of the video comes in, where the bags represent AI and where the protagonists fighting the bags are people fearing technologies and finally accepting it with time. Because of this subject, it completely made sense to me to use AI to generate that video.

VH: Quite often, a new aesthetic or new genres or new art forms are born of these technological jumps, be it the electric guitar or auto tune or the camera or whatever. But I wonder if it’s maybe not going to be like that with AI since what it tends to produce is a vanilla mimicry of human expression.

I wonder too if it feels all the more daunting because it’s doing exactly what I’m doing right now and not something weird that I can’t understand, if that’s why people feel this danger of going extinct or something. I don’t think people felt the same threat from auto tune or the electric guitar. Maybe from the camera.

FT: We could separate AI from machine-learning, which is this more academic approach. Machine-learning was really driven by hardware, and even three years ago, it was very exclusive to people who had access to crazy PCs with video cards and stuff. And, in my opinion, it was a little bit more bland because it was really based on what material you used and the algorithm and if you could run it at all.

Now that you don’t need a crazy computer to generate video, it’s become accessible to pretty much anyone with an internet hookup, in many different cultures, and it’s starting to shift. It’s not just producing emulations and saying, “Look! How crazy that we can do realistic things with nothing.” It’s become more like getting into someone’s dream.

AI: I think AI becomes such a serious threat to art or artists because it’s so effortless, imitating the genius that is the art industry’s main asset – it’s my main asset, to be able to fly. Maybe for that reason, my favorite song on the record is “ICAROS.”

[Editor’s note: the Zoom call drops, then resumes]

AI: Hey. Oh, you’re on opposite sides now.

MK: It switched for me, too.

FT: It's funny because we have this weird duality with Martti where we look alike to a lot of people. I remember meeting Matt [Dryhurst] and Holly [Herndon] for the first time, and they were joking about the fact that Martti and I are so similar.

Now, because of the way the logic works for the live show, Ville will always be on stage – he’s the core, with either Martti or myself. And it became this funny thing because a lot of people think I am Martti.

MK: You're the canceled version of me. You're the canceled version.

FT: Maybe.

MK: Exactly.

VM: The dream is the franchise where I'm actually touring with four different guys who all look like you.

As an artist, your audience always wants you to make new things, but not something too different from what they already like. (Freeka Tet)

AI: Back to Icarus – that myth is one of my favorite childhood stories. When I remember it, I always see Icarus up on the left, the genius father watching to see if the experiment works. My question was always: Who am I? The guy that’s drowning in the end because he flew too close to the sun, which was often my feeling? Or the one who is watching and thinking about what could happen in the future? I think everything of this is in that song.

FT: It’s actually the second song we did together, really early on, after I stopped being just a creative consultant for AS’s live shows and some of the visuals. It was like a first date, where you start to exchange what you have in common. We kept talking about when we were teenagers, playing in a metal band or a punk band, and this song came out of this emo part of us.

As an artist, your audience always wants you to make new things, but not something too different from what they already like. The first part of “ICAROS” is that new thing, without any beat, and the second part is 2017 Amnesia Scanner remixing the song and doing another version of it. That became the DNA of our approach together, doing all the new stuff at the same time. It’s this kind of meme-frying, constantly reprocessing our own shit.

VH: The original song was used in this livestream we did during Covid, where Freeka built a small version of the Oracle sculpture – really, a smaller version of the AS animatronic, which basically took its shape from a Japanese stress ball – and integrated it into this small drone.

AI: It’s interesting that the Oracle comes up over and over again. It’s a prosthetic in your work, just like replacing a human voice with an auto-tuned one or a “Frankensteined” one. That’s also how you’ve described your part to me, Freeka, like an arm that became an instrument.

FT: In the Amnesia world, it’s always this blend of prosthetics and highly accessible props, like cheap Halloween accessories. The AS logo is like an alternate version of Alibaba’s, and the genesis of Oracle is that the guys just bought this robot on AliExpress to be their singer, without really knowing what it was. That’s why the animatronic has this kind of mystical quality.

AI: I remember that, when I revisited the Icarus story later in life, after I’d seen some depictions in paintings, I was thinking, “What? The guy dies? He falls down from the … it doesn’t work?” Because the only depictions I saw were of him in the sky, and not him drowning.

VH: Yeah, true. We always see pre-peak Icarus.

MK: It’s a kind of key part of the story, though, that he …

___

HOAX, release 148 from PAN records, is available for purchase as a vinyl or digital album on Bandcamp.

Ville Haimala has independently written and produced music for and with FKA Twigs, Holly Herndon, and Anne Imhof, among other artists.

Martti Kalliala is an architect, cultural critic, and co-founder of the creative think tank Nemesis.

Freeka Tet is a multidisciplinary artist, designer, programmer, and performer. He lives and works in New York.