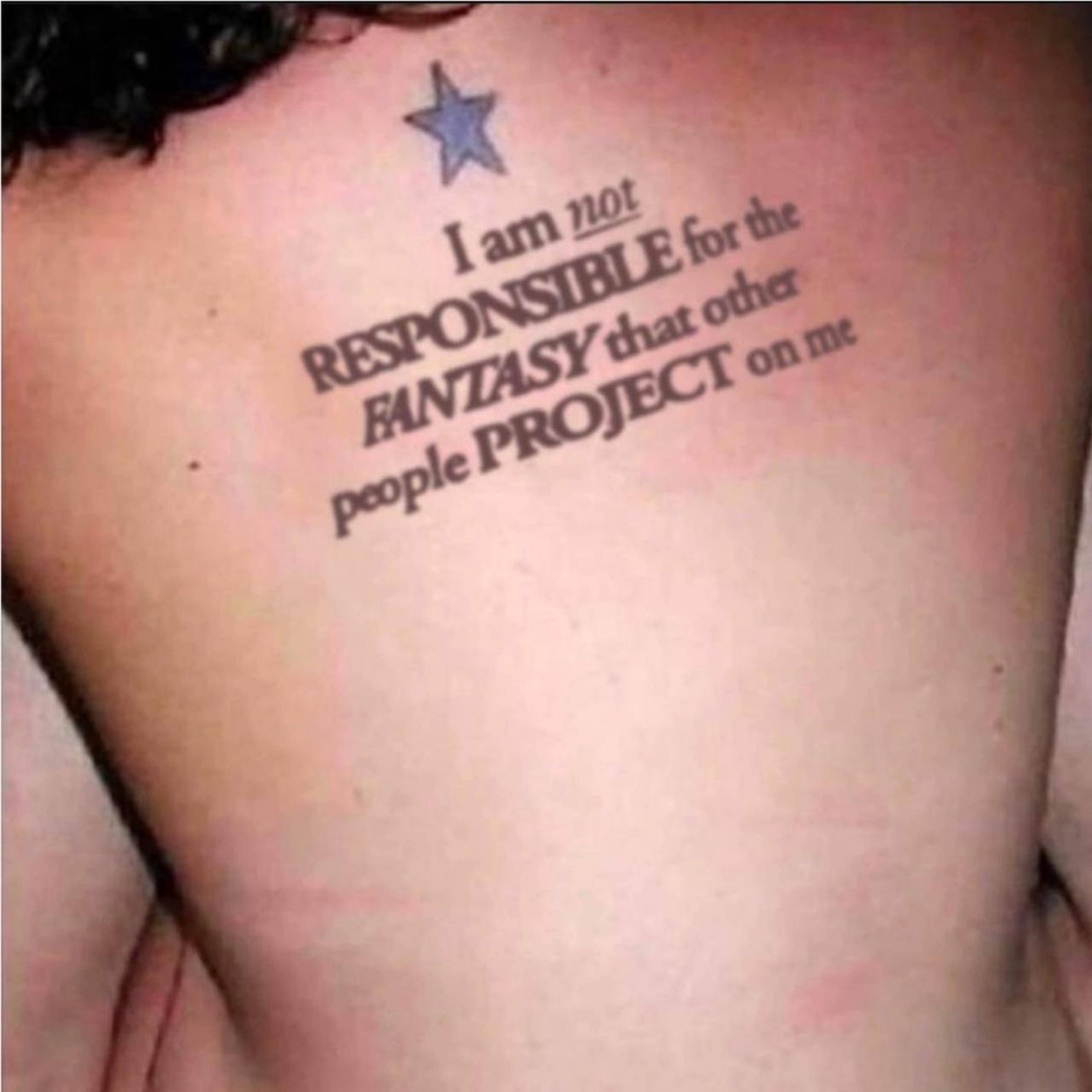

The image of a bare back with a whittled waist. Just above the hip: faint, once cord-bound red marks. Maybe slapped at the top where the color fills a quadrant. There’s a tattooed star on her neck. Black-outlined blue. Below it reads:

I am not

RESPONSIBLE for the

FANTASY that other

people PROJECT on me

The end of each line falls on the reddened part of her back.

It was previously posted by @fridacashflow, née Gabrielle (“west indian angel ~ nyc/London/la” reads her Instagram bio), in November 2022. This is important because it’s hard to pin down the internet. And because when you try, the old is redone, then new. All you have to do is hit it again. Refresh, return.

This picture reappears in a slideshow of the 2022 version of supermodel @bellahadid, née Isabella Khair Hadid (Palestinian & Dutch). In the same set of images, there is a screenshot of a text exchange where someone responds to a photo Bella has sent of herself, legs crossed in a swivel chair, wearing an oversize, black leather coat that reads like a cape at a hair salon. Her eyes are closed so the makeup artist can apply eyeshadow. The gray-set text reads, “Sleepy girl I love you.”

@fridacashflow Instagram post, 19 November 2022

The next slide is from “Dependency Demographics,” a 2017 performance series at Hamburger Bahnhof by artist Analisa Teachworth, a collaboration with Jonas Wendelin: a blonde woman has an iPhone sticky-taped to one side of her face. Her avatar is beaming out of the screen, a near wink.

Then, a slide of some basic-witch paraphernalia: sage, shells, crystals, candles; two slides of numbers (on buildings and cars) are an if-you-know-you-know nod; and two slides of IV drips or blood draws. Next to last, an aerial self-portrait of Hadid. She has on a winter hat and earmuffs, her brown hair braided into three pigtails.

The final slide is of a beautiful woman wearing a red scarf, which matches the makeup blood smeared on her face and neck. She holds a handwritten sign that reads: “You Can’t Burn Women Made of Fire.”

@bellahadid Instagram post, 21 November 2022

The “i” has a flame drawn for its tittle.

The comments below range from support for Bella’s self-care to support for the freedom of Iranian women. Suddenly, the app notes: “Comments on this post have been limited.”

I first saw the marquee image: wounded back asking for relief from the onlooker’s projection, screenshotted in the Instagram story of nineteen-year-old model @alydagrace, née Alyda Grace Carder. Unlike Bella, she’s still kind of a model’s model: not recognizable by name to the public, but outward-facing, with wide-set blue eyes, red hair, and long legs. Her avatar is the chainmail-bikini-wearing heroine Red Sonja, who first showed up in the comic Conan the Barbarian (1970–93), orphaned by mercenaries. Her superpowers were granted by the goddess Scáthach with one caveat: she couldn’t fall in love with any man she hadn’t defeated in combat. If you are knowingly seen, someone is doubting the sincerity of your performance. Lo-fi-diluted, the screen is the opposite of armor. In pixelated physical form, identity is not integrated with spiritual being; volition is filled in by everyone else.

It’s an ancient story: the impossibility of being the desired vessel and having thoughts about that fact. The updated, online version, like our Bella-nymph, allows for self-removal; deletion as refusal. When the body is cut off from the soul, coldness proffers control.

Jeune fille 2.0.

There’s long been talk of a Tumblr sad girl, of pastels and magic sparkles, of wide-eyed girl-women with an air of impending doom.

The nymphs that tear through the ages are frozen on paintings and urns. “Pathosformeln are made of time – they are crystals of historical memory,” writes Giorgio Agamben in Nymphs (2007), borrowing from art historian Aby Warburg. Agamben’s book-length essay cites a range of subjects exploring female representation in iconography. One is Henry Darger’s In the Realms of the Unreal (2002), the outsider artist’s legendary 15,145-page picture book about seven girls in revolt against physical and emotional abuse in the material world (“serial variations of one Pathosformel that we can call nympha dargeriana .”) It is an endless novel, a painstaking documentation of a band of girl-spirits; an early signifier of the linguistic turn of “scroll”?

Now, a more timely legend of a nymph. One that goes: there was a girl – furious and sad, but empowered online – who live-streamed her suicide.

She watches over us. You can’t kill a woman who’s killed herself. Post-mortem, her image is repeated and hollowed, at a far greater speed than ever before.

Analisa Teachworth and Jonas Wendelin, Dependency Demographics, performance documentation, Museen zu Berlin at Hamburger Bahnhof, Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin, 2017.

This showed its almost-analog self neatly in Sofia Coppola’s 1999 film adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides debut novel, The Virgin Suicides (1993). The five beautiful Lisbon sisters at the center of the narrative end up killing themselves (the first by impalement on the symbol of idyllic suburban life, a picket fence.) Telling the tale is a collective of young men who live in the neighborhood and obsess over the hazy mystery of the dead girls. The Lisbon sisters’ mass suicide assures they will live forever as beauty and youth “whether as an isolated film still or a mnestic Pathosformel,” Agamben chimes in.

Their deaths declare both a desperation to escape suburban Gothic idolatry and a desire to remain longed-for female objects.

Over the past few years, I’ve seen the Lisbon girls resurface online in various forms, one being a slide on the account @imsorry, which promotes I’m Sorry by Petra Collins, the photographer Petra Collins’s clothing and accessory line. The post was a still of the sisters, with white, small-caps text declaring, “lisbon girl summer.” These nymphs are generated figures flashing in the in-between. Film stills, but not still.

Henry Darger, 172 At Jennie Richee. Storm Continues. Lightning strikes shelter but no one is injured, mid-20th century, watercolor, pencil, carbon tracing, and collage on pieced paper, 61 x 275 cm

Collins’s website explains the clothing line as “A sartorial translation of her photographic vision (that) captures the interiority of girlhood with sincerity and wit.” It notes her style as one “of a new wave of millennial-directed feminism, capturing the awkward beauty of early womanhood through her dreamy, pastel-tinted photographs.” Spectral evidence of this jeune fille 2.0.

There’s long been talk of a Tumblr sad girl, of pastels and magic sparkles, of wide-eyed girl-women with an air of impending doom, like singer Lana Del Rey. There is something else, though, a palpable push for distance from this kind of hysteria.

English philosopher and theorist Isabel Millar said to me that the protagonist of my novel I Fear My Pain Interests You (2022) – a young, lithe actress-type with a physical pain disorder who describes her story from an aloof perch – represents a kind of inversion of hysteria. The Lisbon sisters kill themselves on the page, whereas my Margot can’t feel anything from the start. She lives momentarily somewhere between land and air.

Still from Sofia Coppola, The Virgin Suicides, 1999, 90 min

This outside is without picket fence. It is outer space-Interweb. This young woman flickers on and off. She shows up to disappear.

She’s an angel who we see again and again. A heteronormative visitation in various forms. It’s all sorts of tacky, but easy to aestheticize: ice queen with red contact lenses; sprite in short skirt and knee socks. She is the kind of cool that comes from a distancing instinct. You’ve never met her IRL.

In contrast, we may fall back again on photography from a time when artists had existing intimacies with their subjects. Face-to-face histories that can be felt in the logged moment. In the images of Nan Goldin, recently celebrated in the documentary film All the Beauty and the Bloodshed (2022), no one wears color contacts. Or if they do, only they know. The scenes are narrative, but tender in a way that happens when people share connections within the frame and behind it.

The body remains a messenger that can dance and fuck, that can cross different borders through living seduction.

Michella Bredahl is an example of another contemporary artist whose photographs aim to accomplish this, capturing real-time vulnerability in domestic spaces. Cut to the late Corinne Day, who also shot her friends and whose produced photos somehow managed to capture a documentarian quality. Enter the iconic Kate Moss outlined in Christmas lights.

This image of Moss wearing a barely visible gold cross looms large over us: One hand on hip, below the black, ruched, tulle elastic of cheap animal-print underwear, Moss leans to the right. The other hand seems to hold her up on something unseen. She wears a pink tank top that hangs loose on her flat chest. Her head is cocked to the left, hair pulled back, eyes lined only at the bottom. A strand of gem-shaped Christmas lights outlines her silhouette, held in place by visible masking tape.

This is our patron saint, Cipher.

There was a time when no one outside of a tight inner circle heard Moss talk. It was a thing. She didn’t give interviews. Day’s Moss – a good portmanteau of this ethereal creature – speaks, but in the collective voice of anyone.

She’s whatever you want if you’re not her. Good and bad.

@petrafcollins meme, 18 February 2022

Another Tumblr image: the Nan Goldin production still of the ticket girl from Variety, the 1983 film written by sometime-vessel writer Kathy Acker. In Jason McBride’s biography of Acker, Eat Your Mind (2022), he writes that her old friend Jeff Weinstein said, “a lot of people projected a lot on to her. She had projected a lot onto herself. She never quite found a comfortable, safe position between these two things, constantly exposing herself like a raw nerve and then fleeing when that nerve was touched.” This is an early adoption of our post-Tumblr-sad-girl phenomenology, a similar ouroboros.

In her book In Memoriam to Identity (1990), Acker says, “Writing is one method of dealing with being human or wanting to suicide cause in order to write you kill yourself at the same time while remaining alive.” She fell in love early with the internet – and even dated one of its cyberpunk guardians, R. U. Sirius, of the magazine Mondo 2000 . Out of body. Online.

The multidisciplinary artist Carolee Schneemann left a direct message for her friend Acker (who sometimes gave herself the form of a black tarantula) in her 1974 artist’s book Cézanne, She Was a Great Painter : “for The Black Tarantula OUR CIVILIZATION IS TO SPEAK TO EACH OTHER/ CIVILIZATION IS THOUGHTS OF OUR BODIES.” Despite advances in technology, civilizations have always had trouble communicating. Each independent one has its own form of writing that the others can’t understand. The body, though, remains the same, a messenger that can dance and fuck, that can cross different borders through living seduction. One’s captured form can translate into empowerment, but often at a net loss – submitting to existing cultural restraints, which are still, smirking, arcane, and puritanical.

Michella Bredahl, Siblings Martha, Alma, Asta and Olga in their home, 2022

In an essay for the publication accompanying the UK’s first retrospective of Schneeman’s work, which took place at the Barbican in 2022, poet and author Eileen Myles writes, “And CS was gorgeous. And it’s an important part of the art. As all one’s powers are.” Myles goes on to talk about how beautiful Schneemann’s body was. “It was just a fact. I think that’s the point in so many ways. If you are blocking me for being female I will thrust the magnificence of my armature in your face. That’s the god touch. It’s the performance of women. It’s war.”

This is different from the ubiquitous low-res image, which happens in a short time. Recall the women we opened with, as well as Red Sonja’s superpower, given with the guarantee that she couldn’t fall in love with any man she hadn’t defeated in combat. Somewhere in comic-book land, someone whispers: she’s hot, but what loser wants to take her home? Schneeman’s performances and films have. It’s easy when a living, breathing body no longer distracts onlookers. When Schneemann was alive, her 16mm experimental film Fuses (1967) screened to a room of outraged Cannes critics. They were aghast at a lack of phallocentric pornography, outraged to witness the egalitarian exchange of heterosexual intimacies.

French filmmaker Catherine Breillat dealt with her own extremes, having written and published a novel at seventeen that was then censored to those under eighteen, ostensibly denying her own ability to reread it. (It is of note that both Breillat and Schneemann’s fathers were provincial town doctors, the go-to men for bodily concerns.) Breillat’s own narratives, both books and films, recall the old-school magician trick of cutting a woman in two, but it is a bifurcation of flesh – sex – and spirit. Film historian Douglas Keesey analyzes her characters’ difficulties with psychic and corporeal integration, noting numerous freeze frames of young girls’ faces, fixed images that allow distance from cycles of shame. Breillat herself writes, “The young girl exists only in order to cease to be. She is a being who commits suicide. Who passes from a future where she has everything ahead of her to the probable banality of her destiny once it has been sealed.”

A body in a scene goes still, but it circulates to reanimate. That dead moment. Get rid of me.

There is a related still from Bertrand Bonello’s 2011 film Apollonide (Souvenirs de la maison close) (translated as both House of Tolerance and House of Pleasures ) in which Julie, one of the prostitutes played by Jasmine Trinca, rests her head on the knee of a man in a pinstripe suit. Her left hand is limp on a waist dressed in a red corset with a lace underbodice. The fingers of her right hand hold the man’s knee. There is a pink flower in her hair. Her shadowed eyes are closed, as are her red lips. The English subtitle tells, “Tonight just pretend I’m dead.”

Deadness is important – and that is the story of this bordello at the start of the 20th century. Everyone is there to “do business” in a “false world.” Stills or screenshots swim around similar to those from The Virgin Suicides . Groups of four or more almost-twenty-year-olds, nude or in seduction mode. A screenshot kills the life in a movie.

A body in a scene goes still, but it circulates to reanimate. That dead moment. Get rid of me.

I’m sorry I live here now in the non-physical infinity.

Carolee Schneemann, Meat Joy, 1964

Recently, I saw a performance that galvanized this idea through its own inversion. Monica Mirabile presented all things under dog, where two things are always true at Performance Space New York, a choreographic production with music by ADR and Eartheater. The audience moved along with the performers through rooms and sets, including one of a long table laid for a familial meal.

Joy was present in this 3D space. The scene spotlighted the beauty of sharing sustenance – what it takes to live: food, breath, sex – with a group. The show notes say that Mirabile is also working through grief (in part from the loss of her father), carried by these systems of support.

Agamben writes of Renaissance dance master Domenico da Piacenza’s seminal essay on “phantasmata,” the image affect. “For Domenico, dancing is essentially an operation conducted on memory, a composition of phantasms within a temporally and spatially ordered series.”

– unfeeling.

Afterlife is another kind of animation. Streams of images can themselves catch fire, gassed up by whatever you want them to be.

Monica Mirabile, all things under dog, where two things are always true, performance documentation, Performance Space New York, 2022

___

– This text appears in Spike #74 – After Beauty. You can buy it in our online shop –