Comedy is the motto of this year’s “Curated by”, a festival that brings together international curators and artists for a temporary take-over of Vienna’s galleries. The first association that came to my mind was Dante’s Divina Commedia, alongside the question: which circle of hell are we in at this moment? Hard times for artworks that want to be intentionally amusing. Despite my initial skepticism, the outcome is broad, with varied interpretations of humor and its languages – the relationships between comedy, ethics and sexuality, tricksters and harlequins – providing a stage for critical reflection. Hello Vienna!

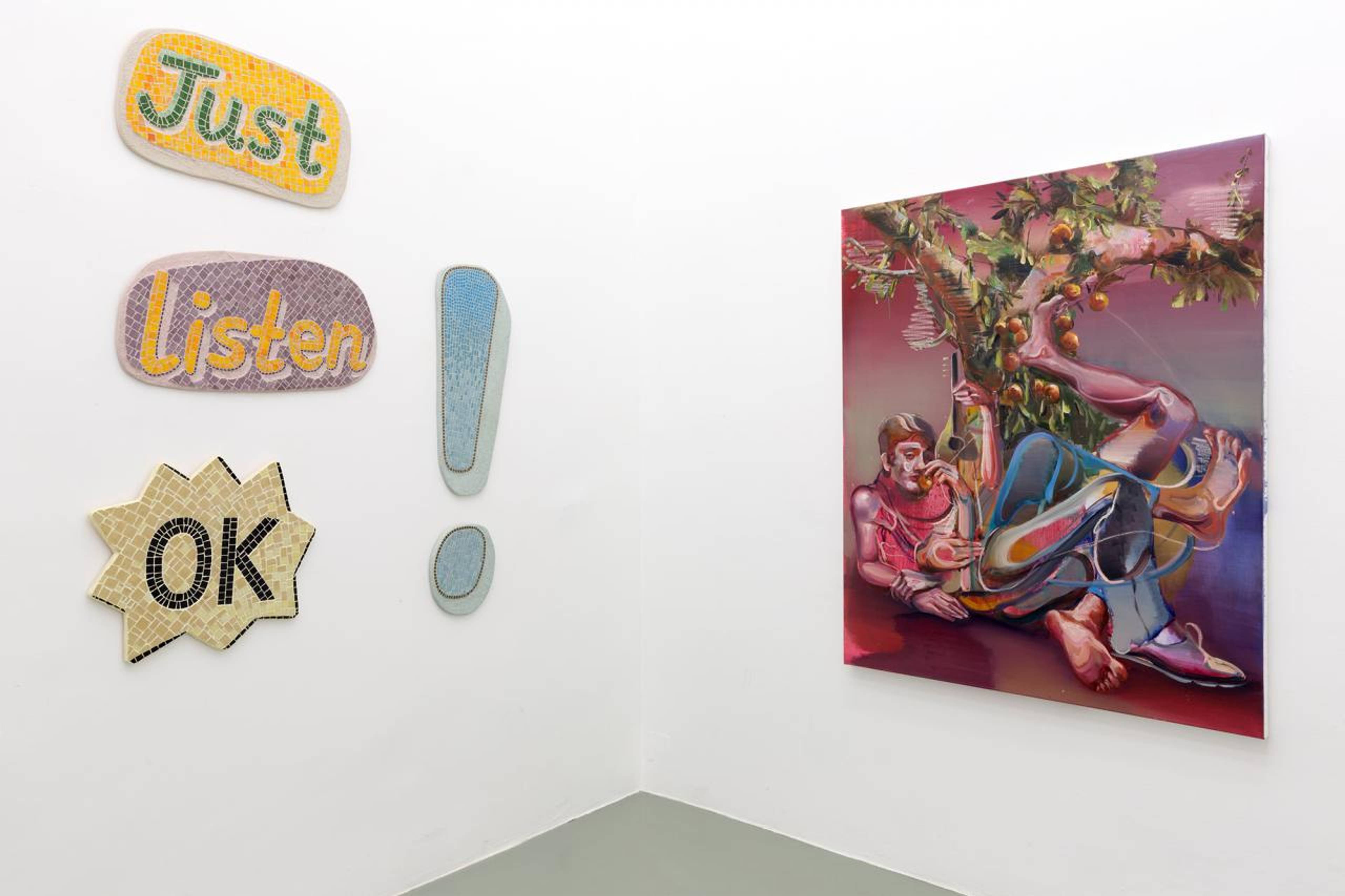

View of “An Incomplete & Unreliable Guide to Social Media War Room,” curated by Valentinas Klimašauskas at Georg Kargl Fine Arts. © Georg Kargl Fine Arts

Nina Sarnelle, Big Opening Event, 2019, HD video, sound, colour, 29 min.

At Georg Kargl, the Dante-esque circles of hell resonate well with what curator Valentinas Klimašauskas calls a “Social Media War Room”: monitors mounted frame to frame on a scaffold discharge videos like bullets. The sound of the works, made by more than a dozen artists, is audible only through headphones, while the soothing melody of an Eric Satie piano composition wavers across the space. Viewers share a position with some mannequin-like works and sculptural placeholders by Jakob Lena Knebl, Paul de Reus, and Nedko Solakov, but the non-stop videos take up all our attention. Impressions from a rave, Amazon parcels moving across a conveyor belt, a young woman in a subway holding up a protest sign, a homeless person at a station: it takes time to figure out which work is by whom, and in the end, doesn’t seem to matter much anyways. (If you’re interested, though, the videos are, amongst others, by Agnieszka Polska, Ulyana Nevzorova, Anna Daucikova, and Nina Sarnelle.) Staring at the wall of flickering monitors is the equivalent to browsing the web, switching TV channels, or scrolling social networks: contexts are conflicting or missing and messages get blurred. Upon entering the gallery, we see Lindsay Lohan desperately trying to escape various paparazzi’s cameras in a clip by Jaakko Pallasvuo – televised tragedy made to amuse the audience.

View of “May Not the Soul Be as Balloons,” curated by Poetry Machine at Galerie Crone. Photo: Matthias Bildstein

At Crone, the AI-based text generator Poetry Machine, invented by media theorist David Link in 2001, helped shape the curatorial concept of the show “May Not the Soul Be as Balloons”. Fed with the essay by Estelle Hoy that serves as a thematic guide to the festival, the machine selected additional words and phrases from the web associated with the original text to generate fourteen detailed descriptions for (speculative) works. Artists were then invited to create paintings, sculptures, or installations based on each of these semantic clusters and their linguistic chaos-cosmos.

The carnival main with parades from water and surface. But her mainer process wish the most conscious. The water changed that this dream is psychic to systems. They make surface rather than fashion sensory for thought waters.

Rosemarie Trockel’s reply to this functional nonsense is Machine Wash Cold (2021), a digital collage where the text “8/8, holiday” adorns two sleeves containing white vinyl records. Other responses to the computer’s prose take the entire thing as a conceptual challenge, because we all know: the first rule in comedy is “be funny”, and the second, “a joke is not funny if you have to explain it”.

Tanoa Sasraku, O’ Pierrot, 2019, 8mm film, 13:58 min

The group show “this is a love poem” at E.X.I.L.E., curated by Cindy Sissokho, takes on a more political tone to reclaim the language of humor through a Black feminist lens. Tanoa Sasraku’s O’ Pierrot (2019), a cinematic reappropriation of the Commedia dell’Arte figure of Pierrot the Clown, explores the quest for British identity from a lesbian, mixed-raced perspective whilst referencing minstrel troupes’ racist caricatures. Mona Benyamin’s sitcom-like Troubles in Paradise (2018) takes humor as a way of coping with trauma and loss, particularly in relation to her life in Palestine. The artist’s parents, who don’t speak English (they read their lines from transliterated title cards), are made to perform jokes ranging from misogynist to openly racist. The canned laughter remains the same throughout the video, while the viewer’s discomfort at witnessing these hegemonic forms of humor steadily rises. Comedy turned against itself can be an effective tool for shifting narratives, an unapologetic form of resistance – and this exhibition is perfect proof.

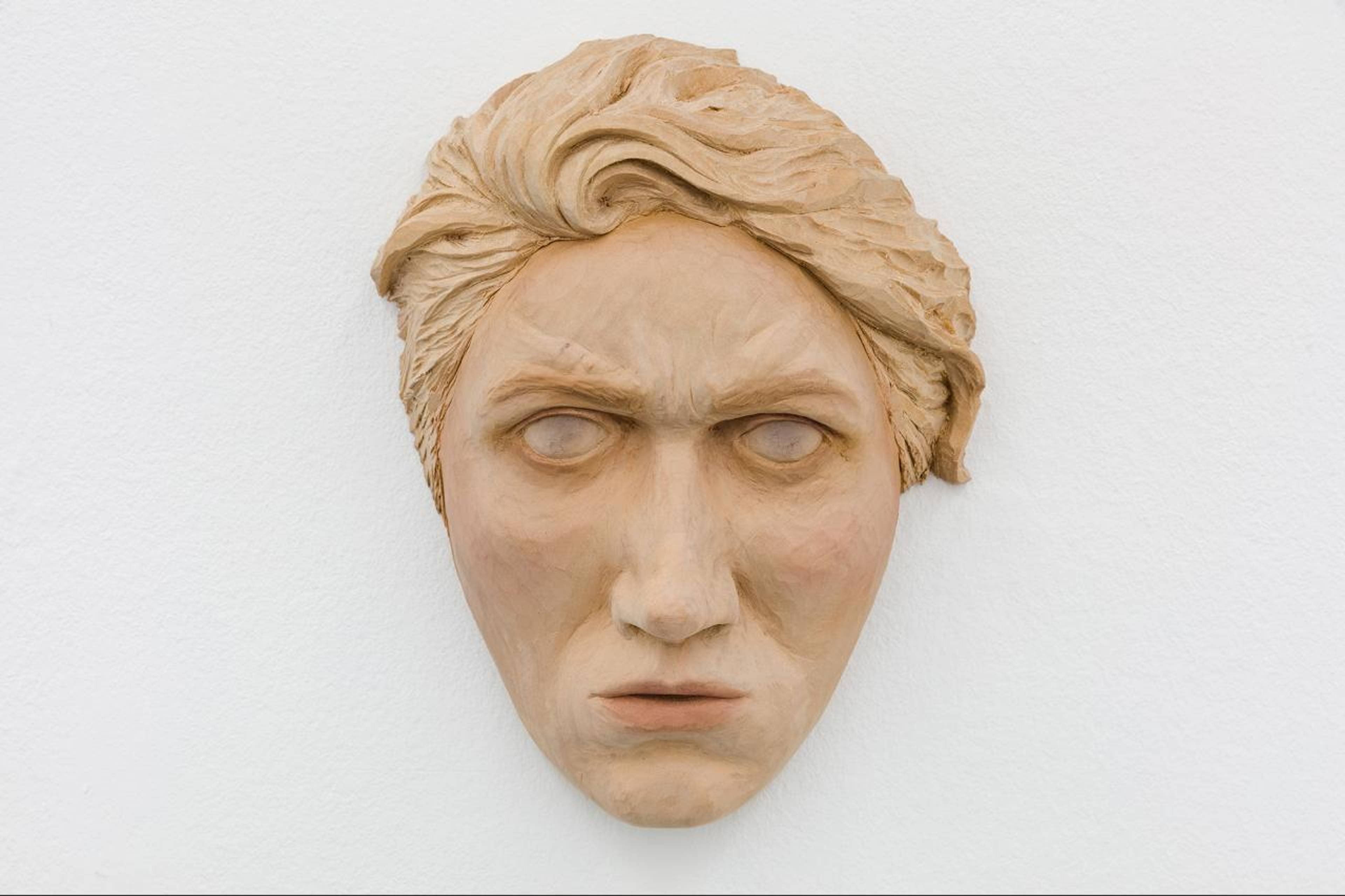

Beth Collar, “Thinking Here Of How The Words Formulate Inside My Head As I Am Just Thinking (4),” 2016–18, lime wood, cosmetics, 16 x 20 x 8 cm

At Galerie Martin Janda, Francesco Pedraglio reclaims the language of humor through poetry, too, albeit in a less obviously political way. “To Do Without So Much Mythology” are two exhibitions running parallel – one visible in the gallery space, the other invisible, consisting of spoken pieces by writers and artists. The visible show presents paintings by Kostis Velonis and Lukas Thaler, Simon Dybbroe Møller’s laconic photos of “young cultural producers”, and fascinating masks by Beth Collor that each highlight her male and female features (Thinking Here Of How The Words Formulate Inside My Head As I Am Just Thinking [2016–2018]). The soundtrack is darker, with short stories read by Holly Pester, Sarah Tripp and others. It insists that comedy, whatever form it takes, is a ritual – an agreement between a speaker or performer and an audience. It needs a shared agreement, a frame of sorts, activating its power to subvert the realities that are hard to bear when taken seriously.

Liesl Raff, Liaisons (detail), 2021, latex, rope, metal, dimensions variable

Entering Sophie Tappeiner gallery, heaps of male clothing greet the visitor. Part of Lisa Long’s “Put a Sock in It!”, they are relics of a performance guided by Reba Maybury, an artist who also works as a dominatrix. Submissive white men are her medium, and for Used Men (2021), a bunch of them took off their clothes on the artist’s command. Naked men in a white cube, sounds like the setup for a good joke. In this case, comedy tests how pleasure, authority, and judgement are interwoven: who is actually allowed to laugh about whom? It is not just the opposite of tragedy, but an essential component thereof. “Tragedy plus time equals comedy”, says the age-old maxim adopted by Melanie Jame Wolf in her video installation Acts of Improbable Genius (2021), a reflection on the ideological foundations of comedy and its archetypical tropes (unsurprisingly both rooted in whiteness and maleness). If tragedy is a technology of endurance, comedy its compressed counterpart.

View of “A Sculpture in Search of an Author,” curated by Studio for Propositional Cinema at Layr

Other venues politely ignore this year’s motto in favor of their own micro-narratives. “A Sculpture in Search of an Author”, curated by Studio for Propositional Cinema at Layr, takes a work by legendary artist’s-artist Emilio Prini as a point of departure, imagining responses to an artwork’s instability within a fixed value system. At Artissima in Turin in 2011, Prini “de-authored” a sculptural work of his the moment an Italian museum was about to purchase it. The performative act of rescinding his signature transformed the piece into a bunch of valueless materials that ended up in the gallery’s storage room. At Layr, an empty stage represents the negative space that was left behind in the wake of Prini’s gesture. It now serves as a symbolic platform where artists including Cesare Pietroiusti, Anna-Sophie Berger, and Margret Honda imagine its future uses. Responding to the quest for authorship and autonomy over the reception, distribution and completion of a work, their names sign a contract that defines what actually constitutes an artwork. “This drawing will be completed by the artist after his death with the use of super-natural means of production”, says the text on the bottom of an empty piece of paper that Pietroiusti distributed. Chocolate ladybugs crawl on the walls in a work by Sung Tieu with Vu Thi Hanh (Ladybirds, 2021), while Honda’s film rolls stored in their cases – she calls them “retired works” – appeal to our imagination of what they might contain.

View of “Esben Weile Kjær: HARDCORE FREEDOM,” curated by The Performance Agency at Zeller van Almsick

View of “Tricksters: Robert Breer, Neïla Czermak Ichti, Rhea Fowler & Micaela Tobin,” curated by Sarah Johanna Theurer at Gianni Manhattan

Audience involvement – a key aspect of comedy – seems to have been part of Esben Weile Kjær’s “HARDCORE FREEDOM” show at Zeller van Almsick. A two-day party performance transformed the gallery into a mix between nightclub, art space, and living room. Seven people must have danced and drank, celebrating youth and freedom (and destroying the space in the process). After the opening weekend, what remains are the leftovers of their controlled escapade, silver cubic balloons still hanging from the ceiling, the huge loudspeakers, the empty champagne bottles and half-burned sticks of sage. The melancholic air that this setting emanates is intentional: after excess comes depression.

At Gianni Manhattan, Robert Breer’s “Floaters” hover across the floor so slowly that they hardly seem to move. They look like DIY anticipations of today’s robotic vacuum cleaners. Sometimes they softly collide. One ( Tucson #2 [2009]) looks like an animated rubbish bag: a ready-made full of tender humor. I could watch them forever, drawing their circles, which are neither hellish nor divine, but clever and comic: their play is a perfect emblem of the times.

___

“Curated by: Comedy”

Various galleries, Vienna

4 Sept – 2 Oct 2021