When I moved to New York in the 2010s, people would joke to their friends better connected than I, “Careful in the car with Alex” or “Don’t drink from Alex’s water bottle.” I got someone to explicate: Alexander Wang famously drugged people without their knowledge, and no one seemed to care. Sure, he got ritualistically canceled in 2020 – but people of deficient taste still don him to go drop off red silk capes at the dry cleaner (I saw this on White Street three weeks ago) and commentators are complaining about his social-media-saturating Ricco bag, weighed down by oversized studs, not because it’s by him, but because it’s boring. “Want to go to the Wang show tn?” a text I received last week read. I went to a rehearsal of a performance-lecture instead.

Everyone still shoots with “Bruce” and “Mario,” though people whine, “I wish we could shoot with Terry.” No matter how lowly you are, if you do or aspire to work “in fashion,” you’re on a first name basis with everyone, except for a few, like Dolce, of Dolce and Gabbana, who once had to record an official apology to Chinese consumers over a sexist and racist campaign. While Kim K reclaimed her fashion image as a “curator” of a D&G show post-divorce, her ex – “I see good things about Hitler” Ye – snatched up alleged pederast Gosha as Yeezy’s head of design. Anyone in the industry will tell you “Jonathan” kicked that dog to death in his office, though only two people have mentioned to me the time he slapped his intern. While some disclose this in excited fake-whispers, others are quick to defend: He’s under so much pressure.

In High & Low (2023), the recent Kevin Macdonald-directed documentary chronicling the rise and fall and – perhaps – rise again of fashion designer John Galliano, former Dior CEO Sidney Toledano offers a dissenting opinion in a recent interview recorded for the film: “The burnout comes from what’s inside,” he says. “Not the work.” When Macdonald tells Galliano about Toledano’s claims, the designer seems baffled. He was doing up to thirty-two collections a year, he says, deciding details down to the eyelash length.

John Galliano and Anna Wintour at a party in Paris in 1993. © Derek Ridgers. Courtesy: MUBI

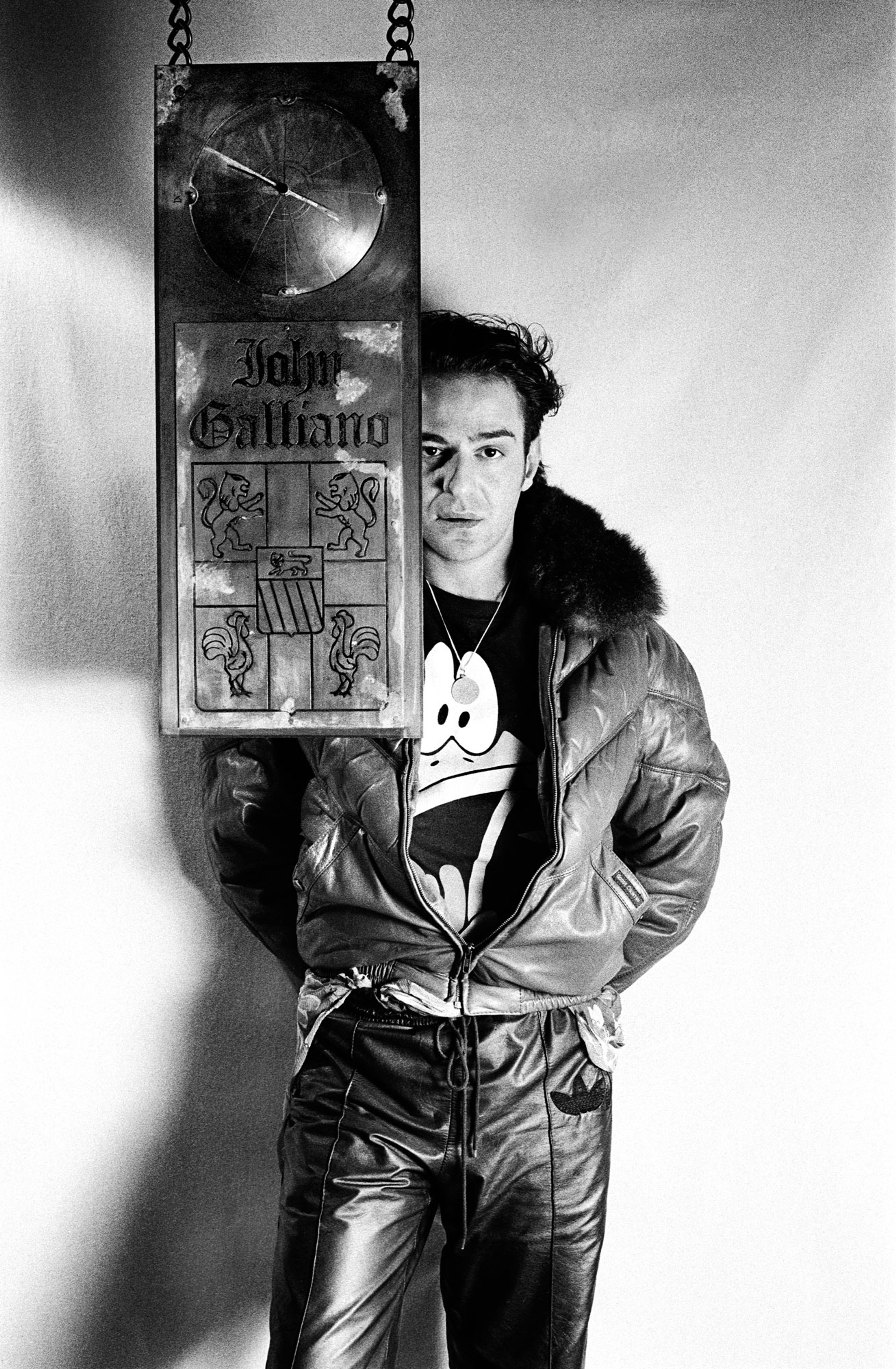

Portrait of John Galliano. © Derek Ridgers. Courtesy: MUBI

John Galliano is and was one of the most inspired and infamous couturiers of the last several decades. Born in Gibraltar, at the age of six, his family moved to South London and he later attended Central Saint Martins, graduating in 1984. Known for costume-y, risqué, narrative-rich garments, his namesake label, launched in the late 1980s, was financially unsustainable. Events – as well as Anna Wintour and André Leon Talley – conspired to get him a job as creative director of Givenchy in 1995. After less than two years, he was put in charge of Dior. From the outside looking in, it was going swimmingly – until what we see spliced into the first scene of the film.

It’s backstage of the Fall 2022 Margiela Artisanal show, judging by the hats. Models mug in blue lipstick and red veils. Eyes closed, hands cradling his knee, Galliano – creative director of Maison Margiela since 2014 – appears meditative. Delicate music wooshes like a true-crime backing track, and intercut, we see people milling outside a 3ème bar, La Perle. Back to present-day-ish Galliano: eyes open. We cut again: In a grainy video, he is smoking at the table of a tabac. Back to the 2020s: Galliano’s craning face. Back to the bar: “No, but I love Hitler. People like you would be dead today,” he slurs, black sailor cap askew.

One of two racist rants Galliano delivered in blackout fugues in 2010–11, the tantrums led to his excommunication from the industry, the 2012 revocation of his French Legion of Honor medal, as well as criminal charges. In this hackneyed opening sequence, we understand the trajectory we are about to indulge as viewers. The film soon provides the classic addiction-narrative set up – his youth of homophobia and abuse, his partying days behind which, we already sense, a shadowy side lurks, and his artistic challenges. Throughout High & Low, Macdonald and his editor, Avdhesh Mohla, blend not only B-roll from backstage and runway footage with interviews by Macdonald, but also Abel Gance’s 1927 Napoléon. The film’s kohl-eyed, queerly dressed namesake protagonist, played by actor Albert Dieudonné, certainly looks not unlike Galliano, an effect heightened when compositionally similar scenes shot for High & Low are sequenced with clips from the century-old movie. At one point, a bit more than midway through High & Low, Macdonald asks present-day Galliano, who’s seated in his tastefully chaotic country home, of his “Napoleonic ego.” To the interviewer, the designer forces a chuckle: “Here you go again. You’re obsessed with that. No, I was not Napoleonic at all.”

John Galliano at a Dior show in 2005 in Paris. Courtesy: firstVIEW

High & Low screened at arthouse cinemas and is available to watch on MUBI, the festival-favored platform. But there’s not much arthouse about the film; one suspects it gets pride of place merely because its content is irrelevant to most audiences. Like recent “high-culture” hero-worship documentaries (among them recently Martin Margiela: In His Own Words [2019], which leaked on PornHub [how high-low], the Amanda Kim film Nam June Paik: Moon Is The Oldest TV [2023], and, albeit with laudable skill, Laura Poitras’s Nan Goldin hagiography All the Beauty and the Bloodshed [2022], which Goldin produced), the bad is either elided or brought to some phoenix-esque redemption in the name of narrative tidiness. In this light, High & Low’s opening reads not only as defensive, but framed by the PR-inflected format, its conclusion foredrawn. However, High & Low is enjoyable enough because, at least, the clothes are beautiful.

Whereas High & Low takes an ostensibly elevated tack with delicate music, low-depth-of-field cinematography, and pensive portraiture, another recent fashion documentary film, Brandy Hellville & The Cult of Fast Fashion (2024), goes low. Directed by Eva Orner, the Max release investigates the punned-upon, youth-focused, one-size-fits-few retailer Brandy Mellville while also glancing under the rug of the fast-fashion industry. Instead of silent film samples and string music, Orner leverages dopamine-pinging social media aesthetics, overlaying interviews with former store employees – shot on bubblegum-pink seamless, the armatures sometimes visible – with social media–inspired overlays, likes and reblogs racking up with delicious clicking sounds.

While “canceling” an artist may or may not be regressive, the exclusion of skeevy photographers or racist creative directors from the industry has less to do with propriety than with labor rights.

Rather than focusing on a lone figure, Brandy Hellville talks to the brand’s store employees while weaving its Fyre-Festival-doc-style exposé with journeys to Prato, Italy, and Accra, Ghana, recording the impact of fast fashion on those who make it and those who are left with its runoff. While High & Low talks of the pressures upon Galliano – as well as the coterie that sustained him and his mythology professionally, like his first-mate Steve Robinson, who died of a cocaine overdose in 2007, or the personal assistants he fired – those from the conglomerate given screentime are the execs (or, in one instance, the exec’s wife: Penélope Cruz), and we don’t see much of the manufacture, whether in the couture atelier or the factories and sweatshops.

Brandy Hellville’s peers – on Max alone this might include the The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley (2019, on Theranos’s Elizabeth Holmes), Quiet on Set (2024, on exploitation in children’s television), and the miniseries Allen v. Farrow (2021, on Woody Allen’s perviness) – tend to deliver viewers salvation in the form of “justice,” which, in US-American prison-fetishist pathology, usually manifests as the comeuppance of a few years in a minimum-security penitentiary, or at least calls for it. (Cancel culture is fake; incarceration isn’t. For his part, although convicted, Galliano didn’t serve time, but paid a 6,000-euro fine.) For a moment, it appears Brandy Hellville will serve just desserts too: News of lawsuits against the company’s systematically racist hiring, as well as its leaders’ Nazi jokes and nefarious deeds, is broken on Business Insider by Kate Taylor. Diet Prada posts the tales. The stories snowball. Employees are quickly spliced together relaying their reactions, alternating their presence with social-media comments and photos of Melville CEO Stephan Marsan. The music rises. “Maybe this will be the time that people rip the veil of elitist aesthetics and expose them for just being a really shitty brand that makes money off of young girls’ insecurities,” a former employee recalls thinking. TikToks of callouts and “Fuck Brandy!” screams accrue amid stories of the employees’ quitting. Is this the end of Brandy?

No such luck. The bad press hit, and Brandy sales continued apace.

Stills from Eva Orner, Brandy Hellville & the Cult of Fast Fashion, 2024, 91 min. Courtesy: HBO

In both Brandy Hellville and High & Low, we see this behemoth industry that draws in more than one-trillion dollars yearly in global revenue as too big to fail. While High & Low recounts the hiring and firing of some Galliano confidantes in addition to its titular man himself, High & Low can’t decide if it’s a film about the falsities of the fashion system’s myth-making or of the legitimacy of its Romantic geniuses against growing corporatization.

Macdonald doesn’t let Galliano off the hook per se – Philippe Virgitti, a victim of one of Galliano’s rants, speaks, and in one bizarre scene, we watch Galliano struggling to recall he staged not one, but two racist tirades, calling upon his boyfriend Alexis Roche to remind him, yes, it happened twice. But the film’s formal blandness tempers the very complications it wishes to tease apart, instead relaying a palatable-enough picture, a brasserie meal of overcooked sole whose béchamel hopes to save it – and, if it doesn’t, at least you’ve ordered Champagne.

While “canceling” an artist may or may not be regressive, the exclusion of skeevy photographers or racist creative directors from the industry has less to do with propriety than with labor rights. If you’re a model or artisan or an overworked designer or one of the half-dozen people that designer employed to light and smoke his cigarettes for him (an example Galliano offers up to acknowledge he realizes it was, in retrospect, “not normal”), a discriminatory boss is a shitty boss. High & Low’s biography fetish (are fashion movies Walter Issacson books for fags?) prevents it from ever peering too deeply at the industry’s structural acceleration, for which Galliano serves as both symbol and scapegoat. Brandy Hellville, without an “artist” to focus on, instead unpacks the web of impact and myth-making from the bottom up. In either case, we are shown a corporate system whose efficiencies and velocities and glamorous magazines or social media pages fuck over employees – highly or lowly as they may be.

John Galliano at Dior archives. Courtesy: Newen Studios, Paris

New York Times fashion critic Vanessa Friedman, a skeptical talking head in High & Low, wrote of Galliano’s mirkin-laced critical success of a Margiela Artisanal presentation this past February, that while “the Margiela show, with its distortions and theater, its lack of obvious commercial intent, represented a riposte” to the fear that “money has won,” interpreting the show as “a solution rather than a symptom may be more wishful thinking than reality.”

If Galliano’s Margiela couture show cannot redeem the cash-flush industry churning out disposable products by the ton each week for consumers as addicted as any prestige pillhead, what role does Galliano’s personal redemption serve? It legitimizes a vintage vision of capitalism, one where bad actors are held accountable, where geniuses are tortured but prevail – and thus the system does too. But Brandy Helville demonstrates that when memory holds less than a fashion season, “accountability” has been beside the point all along. While, for the court of consumer opinion, figureheads may briefly roll, the maison always wins. And as Margiela’s owner OTB Group rakes in €1.9 billion a year (a pittance compared to Dior parent LVMH’s $86 billion), they do. As celebration disguised as amende honorable, High & Low is not absolution for Galliano, but for an industry that no longer needs bothering be absolved. The lesson learned by Marsan of Brandy Melville and his ilk from the endurance of visionaries like Galliano and hacks like Wang is that cancellation is just hype. The ability for PR-scripted contrition to salvage the fashion system belies the fact that the system would have kept churning regardless – so why apologize at all? At the very least, it’s smarter marketing to save your apology for your limited-release special.

Portrait of John Galliano by Barry Mardsen. Courtesy: MUBI

___

Kevin Macdonald’s documentary High & Low: John Galliano (2023) is streaming on MUBI.