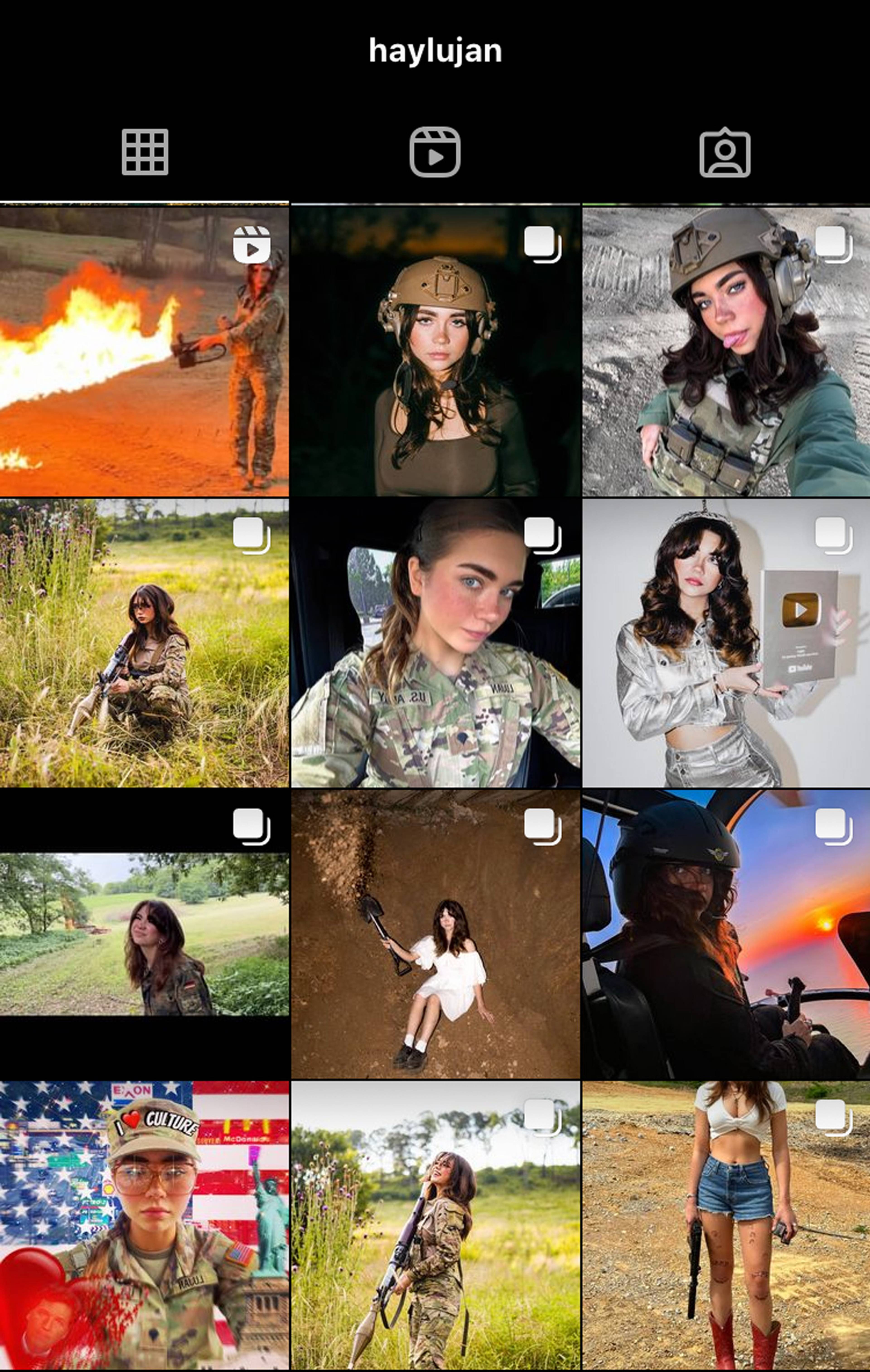

In November 2023, an Israeli woman posted a selfie taken in her apartment lobby mirror. Brushed steel, scalloped mini, pink travel cup. “War days,” read the caption, two heart emojis in blue and white. During this phase of the genocide, commentary surrounded attractive platform users because their appearance lubricated the algorithm to grant Zionist ideology a wider reach. Since 2020, the artist Noura Tafeche has collected materials created by pretty girl soldiers serving in the Israeli and US militaries: viral dances, makeup tutorials, and thirst traps made in the downtime between killing, or at least training to kill, the enemies of empire. Yet creators on army payroll, delivering on state objectives – such as hottie @haylujan (349k followers), who coyly claims to be a “psy-op” – are in the minority. Civilians are happy to make free videos from a self-driven sense of duty, presenting step-by-step recipes as they bake cookies for IDF soldiers, or lifestyle supercuts that omit bombed-out schools and hospitals just a stone’s throw away. I have seen platform realists display how their content fares when they are wearing makeup versus not wearing makeup; when they are 50 kilos versus 60 kilos; when they are built according to crossfit versus cardio – giving us their hard stats, as if attaining attractiveness were a pro sport, the platform’s architecture a stadium. When she chooses to combine her legible hotness with warmongering, the girl develops decorative violence as Sayak Valencia defines it in Gore Capitalism (2010): “allowing public and private spaces to be invaded by consumption with clear connections to warfare.” In these instances, girls game TikTok and Instagram’s platform physics to “decorate” genocidal acts with lifestyle content.

The growing genre of “girl propaganda” demonstrates, in real-time, how this boost is easily directed beyond lifestyle into psy-op territory – or, if it is lifestyle, it is a lifestyle that, uncommonly, shortens the tether to its real, bloody cost. According to Valencia, the defining element of gore capitalism is a “complete lack of clarity about what is permissible and what is not.” Gore is an aesthetic of ultraviolence, the inside-out outcome of brutal acts. Linking it to capitalism, as Valencia does, braids the processes of extraction and domination tightly with their visceral cost. She reveals that theft and murder with impunity are not criminal exceptions to a humanist framework, but its core operations. The seeming “extreme fringes” that produce blood & guts in cold blood are, in fact, at the center.

Delusions, denials, manifestation mantras, and sixteen-step rituals – these are the consumer-symbolic girl’s last, fallible guard against the cruel world and its psychic effects, amounting to the age-old SATC meme: I couldn’t help but wonder, is it time to focus on World War Me?

In 2010, Valencia made an enviably straightforward distinction between broadcast media and reality, pointing out where on-screen narratives inspired personal conduct, as in the recursive relationship between mafia movies and actual practices of gang violence. That argument has since been distorted by algorithmic media, which decorates and normalizes ultraviolence at once, producing Mirror Worlds of explicit gruesomeness and smooth delusion. The platform desensitizes the user to violence’s orders, while breaking (if not entirely) the repression of its existence. The odd, mass collective vibe of numbness and fragility is no accident. Maya B. Kronic, in their 2017 essay “Hyperplastic Supernormal,” deconstructs today’s “intense state of consciousness” as one over-triggered by supernormal stimulus. The supernormal describes any product designed to ramp up desire through the manipulation of instinct and emotion: “harmonised phenomena” that “creates ‘pure aesthetic stock’.” Take content production, for example, where worldly experience is codified and incentivized to generate an ever more finely-calibrated emotional response. A glut of “microaesthetics” and “-cores” that will keep media theorists in employ for millennia are patterned over a nauseating mix of immersive marketing and uninterpretable violence. But anyone who has been on the analyst’s daybed for even one session knows that repression is no fix. Naïve analyses of “the feed” make a semi-charmed novelty out of cognitive whiplash itself, yet the psychic break caused by blending lifestyle and violence is better located in the staggering after-effects of decades of daily exposure. If algorithmic media has strapped our psychology into the passenger seat of a crash-test simulation, then perhaps we have reached a turning point in the experiment. We’ve snapped our model’s neck.

@haylujan’s Instagram grid

What is that model? In a previous essay for WIRED, “Everyone is a Girl Online,” I posited that it is the girl who is the platform’s ideal consumer and commodity, a “technology of subjectivity” that floats apart from any one individual subject. In the ideal consumer state, the girl can achieve peak smoothness through the physical and spiritual anorexia that Tiqqun named “the angel complex.” She focuses on crafting the perfect chassis through which gore can flow: a regulated, well-disciplined and unarousable form that suppresses global trauma in order to maintain the work and consumption routines of empire. See the war days girlie as an archetype. So smooth that everything except capital slides right off, so numb in accordance with the nullifying conditions of the platform, her smiling pliability licensing bad behavior according to basic gender protocols. However, maintaining this position – aspirational and incentivized since the dawn of algorithmic media – has only become more difficult in the age of gore immersion. On American social media, pop-psych videos on emotional detachment and regulation proliferate. What is that, if not an individual’s obsessive strengthening of an internal defense system – the delusions, denials, manifestation mantras, and sixteen-step rituals designed to move oneself out of the emotional intensity of living under The Horrors? These are the consumer-symbolic girl’s last, fallible guard against the cruel world and its psychic effects, amounting to the age-old SATC meme: I couldn’t help but wonder, is it time to focus on World War Me?

Death, not the semiconductor, is the foundational material of techno-culture. Our slippery digital playgrounds derive energy from spilled blood, and cash in by packaging it as entertainment.

Historically, technology and infrastructure have been designed to mute and buff away the bloodshed – not reduce it. In 1948, Swiss historian Sigfried Giedion was already writing of how death is found “in the washing machine, the fridge, canned meat, the sink and the vacuum cleaner. That is, death could be found in every domestic object that helped distance people from abject organic matter and hazards that they might otherwise have to deal with.” Early critiques of capitalism drew parallels with the slaughterhouse. From the sweatshop to the open mine to the forever war, the vicious toll of bourgeois lifestyle was hidden away, just as the animal is killed far from the diner. The implied solution, at the time, was that exposure to these egregious realities would snap us out of consumer blindness. Think of 2000s PETA campaigns or supermodels with cuts of meat drawn on their flanks (in retrospect, kind of slay). Today, any understanding that exposure is not a structural fix comes simultaneous with the acceptance that contending with a world-embedded “attention economy” still requires a tactics of attentional capture.

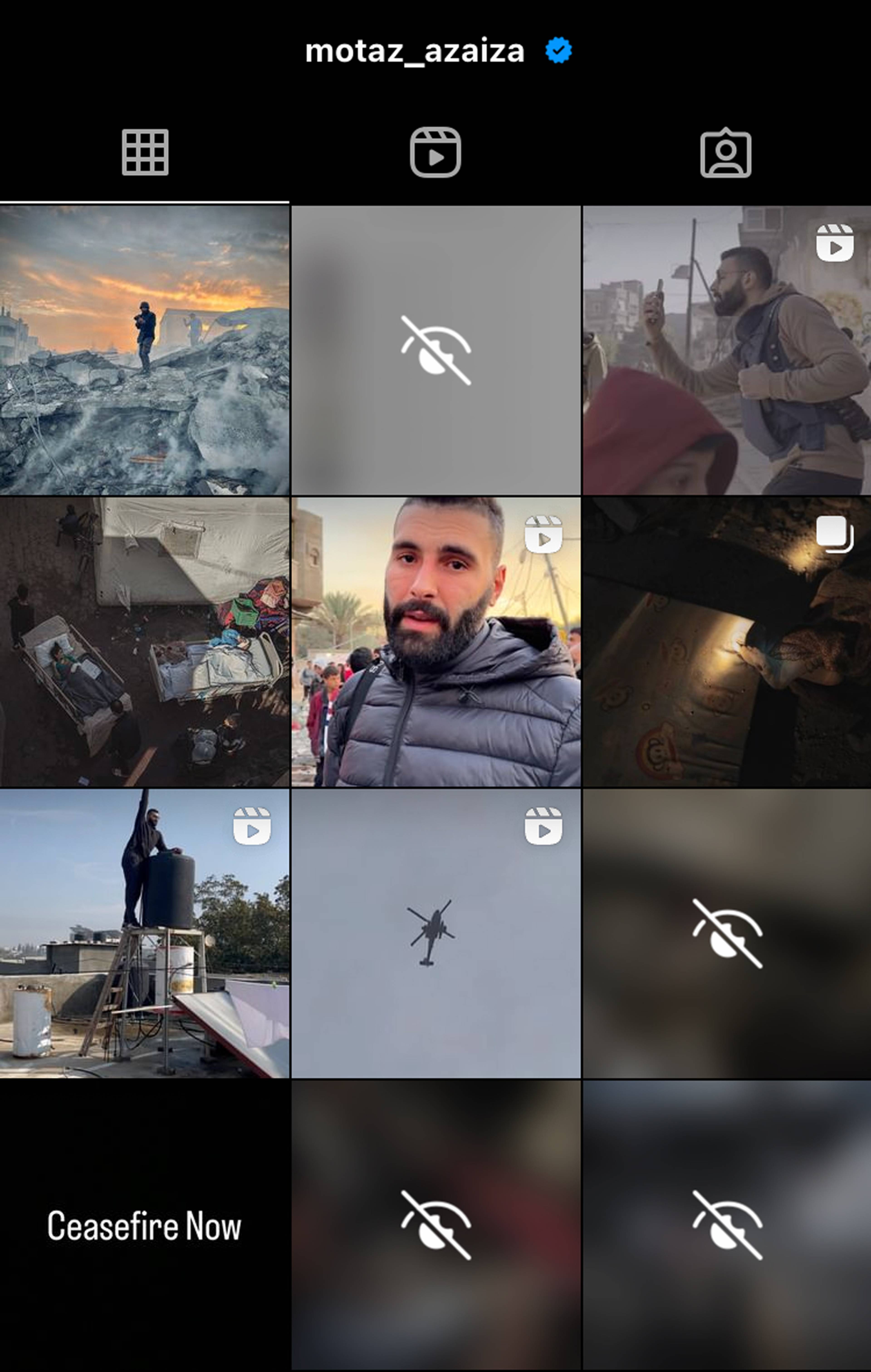

In Common Accounts’ The Death Report (2024) – a comprehensive document on the infrastructure of death, edited by Charlie Robin Jones – the authors consider the Gaussian Blur that hides mutilated bodies from the lifestyle feed under the label “Sensitive Content.” “Sensitive content,"’ hidden by default, implies an insensitive viewer; the blur a literal vellum between user-generated fictions and brutal events. Vellum was once made with animal skin. Apt, to see the bloody musculature of our reality encased by a translucent effect. Sympathy for the activist who implores, “stop scrolling!” or “one minute!” the selfie-video tricking the algorithm out of concealing a perspective that would otherwise be deprioritized by design. Appearing there, begging, is a capitulation to the platform’s monstrous smoothness. Sympathy, too, for the documentarian whose best efforts are coldly excised. On Palestinian photojournalist Motaz Azaiza’s (18M followers) grid, between Gaussian Blurs, there are screenshots of warnings issued by Instagram: We have removed your content. Graphic Violence. Content Removed. Alongside modes of direct address, there are a selection of ways to game it back. Selfies, scrambled text, and symbolic cues resurface pro-Palestine content above the blur to re-sensitize viewership – to route attention off the platform and into more significant action.

@motaz_azaiza’s Instagram grid

“If there is a subject of history for the culture of abjection at all, it is not the Worker, the Woman, or the Person of Color, but the Corpse,” writes Hal Foster in the 1996 essay, “Obscene, Abject, Traumatic.” “This is a politics of difference pushed beyond indifference, a politics of alterity pushed to nihility.” Death, not the semiconductor, is the foundational material of techno-culture. Suicidal factory workers, mutilated mineral miners, traumatized content moderators – not to mention the soldier-cum-gangster who broadcasts his acts of killing: Our slippery digital playgrounds derive energy from spilled blood, and cash in by packaging it as entertainment. If the distancing function of capitalism, and its alienation of the real violence that constitutes it, has been warped by the platform – exposing users nonstop to representations of death, while structurally administering psychic numbing – then there is a hard limit to what further attentional exposure can do.

Facing down the gore paradigm, where everything is permissible, nullified, and exposed, the platform’s ideal girl-subject must be cut open and reconfigured. In their book Cute Accelerationism (2024), Amy Ireland and Maya B. Kronic discuss the “cross-sectioning” of cute characters, imagining an unending cutting of their smooth surfaces only to expose their essential superficiality. “Cut them open and they don’t bleed, but only reveal smooth flat cross-sectional planes of viscera which can be sliced again and again without ever yielding the elusive dimension of depth.” If that is where we are – a paradoxical infinity of blood-steeped surfaces – then we’d better figure how to get through it, together.

Consuming gore turned out to be a kind of psychic bloodletting. A play that allowed me to examine the horrors from a safe but proximate angle, in the way that some say BDSM can help process sexual trauma.

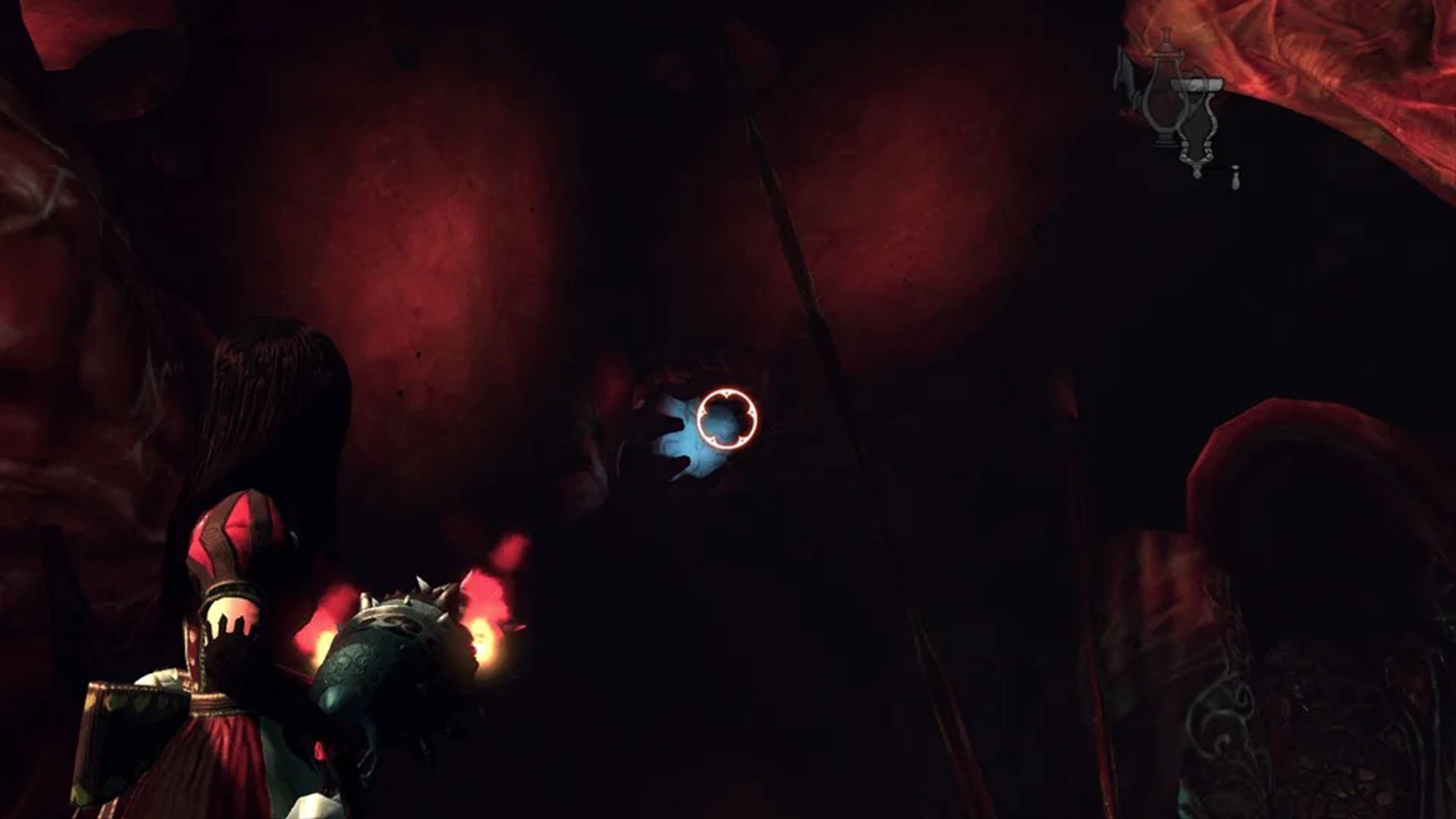

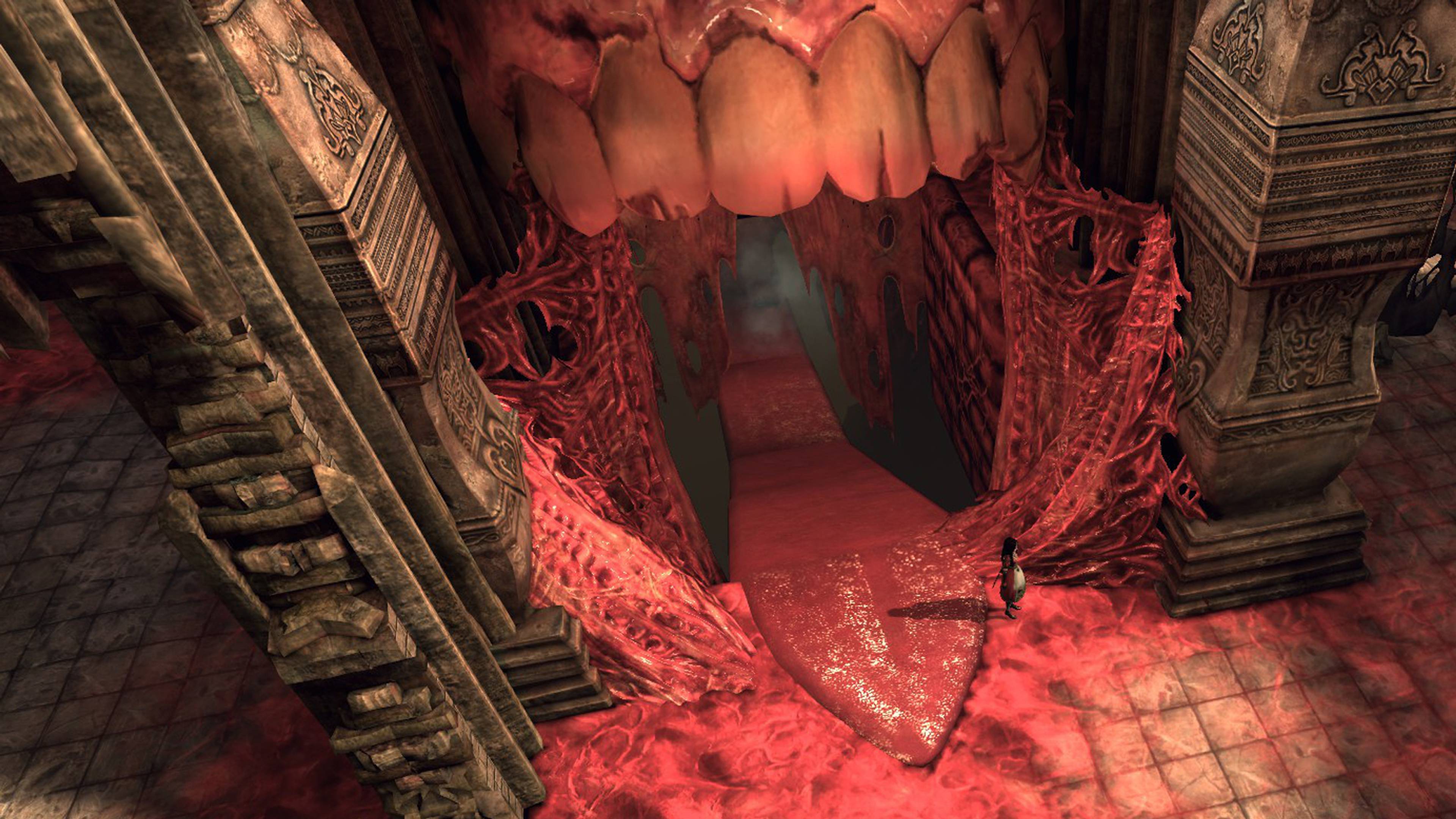

“Fiction fundamentally rearranges the subject,” writes Tamaki Saitō in Beautiful Fighting Girl (2011). After witnessing a live death in 2021, I developed a brief obsession with gore media. Previously, I had no taste for it; anyway, it was the long season of mass killings in my country, so it’s not like I was deprived of reality checks. But to contend with something that rearranged my world – before you experience violence, you are primarily protected by the illusion that it would never happen to you – I had to have my subjectivity “sliced again and again.” I spent some months watching movies that played violence to an unbelievable extreme, gazing meditatively upon heads ripped from spines to reveal a bouquet of ruptured veins, intestines floating in bathwater like some sick soup. The difference between general violence and gore, of course, is not extremity, but mediatization. There is a style to gore that is not necessarily connected to the act and intention of killing. Consuming gore – to be clear, I don’t mean snuff – turned out to be a kind of psychic bloodletting. A play that allowed me to examine the horrors from a safe but proximate angle, in the way that some say BDSM can help process sexual trauma, accessing a necessary intensity without inflicting further damage. Somewhere in the feed, I screenshot some material from the video game Alice: Madness Returns (2011). The mood is early traumacore: Alice stands before a ruined castle, where crumbling bricks are held together by a massive cascade of flesh and blood. Teeth push up through the tissue. One senseless eye glares out over a slippery gash. I watch the gameplay on Youtube, where Alice enters the portal and slides down an infinite tongue, between dark waterfalls of blood, On her way! to kill the final boss – a distorted version of herself who demands she accept cycles of violence as her new reality.

Stills from Alice: Madness Returns, 2011, video game. Direction: American McGee; development: Spicy Horse. © Electronic Arts

For each of us, the platform produces personal para-fictions – which, if you are not in an active warzone or an offline billionaire, become the primary route through which you access others’ realities through their perspective. It is not, by default, an empathy machine – nor is it necessarily a distancing machine – but it is a “narrative machine,” as design theorist Stephanie Sherman defines it. Girls and Gore are fictions analogous to our unsteady relationship with representation and violence. There is an autonomy to these fictions as they operate alongside or on top of reality, shaping and informing our responses to The Real and its myriad concurrent endings. They are not directives or distractions, but portals back into a shared world – where exaggeration, fantasy, and distortion can reverse neutralization. But what can the girl become under the gore paradigm, other than the enemy within? In horror movies, the Final Girl – the Scream-ish trope of the last femme standing – is always the “investigative consciousness” of the gothic or horrific environment. She claws her way through a mutant world, facing down demonic entities that scare her because they don’t resemble anything she’s ever known. Popular analyses of the Final Girl trope – such as Carol Clover’s oft-cited 1992 essay, “Men, Women, and Chain Saws” – see her exposure to abject terror as the foundation of her character development, where survival necessitates overcoming so-called feminine weaknesses to step into an assertive, violent role. In contrast, Elizabeth Gabrielle Lee and Jade Barget’s curatorial project, Fatal and Fallen (2021–24) kaleidoscopes the role that Final Girls play across cinema, beyond the redemption arc. Her desire, fragility, rage and fear are interpreted as the cornerstones of her power, rather than traits that hinder her progress to victory. “Who says that anger and hate have to be ugly?” they write in their joint text on the psychedelic anime Belladonna of Sadness (1973), describing the heroine’s surprise when her descent to Hell is paved with songbirds and wildflowers.

Without a doubt, our world is a decorated hell. And if the prevailing storyline of that hell is an endless End, as Shumon Basar argues in “The Dawn of Endcore,” then we are all pushed towards Final Girlhood, whether we’re ready or not. In the horror canon, the Final Girl often finds her fatality through an initial unwillingness. Her fearful, screaming performance still guides her to winning against all odds. Is that where we’re headed? Gore-sober now, I have a tendency to over-warn my audiences about limitations, toggling in a Gaussian Blur of my own to designate the difference between theory and action. We won’t slip-and-slide down the attentional vector into liberation. The point of understanding how these subject-models and para-fictions interact to intensify and occlude emotion is to develop effective counter-operations. The figure of the girl makes an excellent exoskeleton – one that becomes a seductive decoy, or basic camouflage – that gives some of us a fighting chance to navigate the platform with some protagonal intention, rather than succumbing to the individuated passivity it induces. Otherwise, as in any slasher series, there is a risk that the girl’s “calculable survival” – her continued existence as a numbed-out predictive protocol, an empty chassis – makes her “survival as meaningless as the violence that surrounds her.”

___