“Everyone’s in town for documenta,” our cab driver said on the way to our rental.

“What are people saying about it?” my friend Pujan asked.

“I don’t know. Everybody’s speaking English.”

We had arrived from New York for the opening of documenta: a city-wide exhibition that has happened every four, then five years in Kassel, Germany since its inception in 1955. Every four and now five years, documenta — prestigious, historical — sends a powerful signal through the international art world that in many ways sets the terms of the conversation over what art is and what art can do.

This year’s signal is that art is social architecture. The curators are ruangrupa, an Indonesian collective based in Jakarta, that has formed around their ongoing collective practice, lumbung. Lumbung is not a theory, it’s a practice of gathering and distributing resources, which can be material (e.g., money, project space, alcohol) or immaterial (e.g., skill, labor, friendship). The goal of lumbung is not to create art objects for a speculative market, but the sustainability of its participants. Art objects form incidentally, like a snake’s skin, as either the documentation, avatar, byproduct, residue, evidence, or satellite of a communal practice happening either elsewhere or during the documenta lumbung program events. Any profits that come from the sale of art objects returns to a collectively owned common pot, regulated by lumbung participants in meetings called majelis.

Baan Noorg Collaborative Arts and Culture, The Rituals of Things, 2022. Installation view, Fridericianum, Kassel, 2022. Photo: Nicolas Wefers

*foundationClass*collective, Becoming, 2022. Installation view, Fridericianum, Kassel, 2022. Photo: Frank Sperling

If one of the artists or collectives wanted to use documenta funding, which was pooled in the lumbung money pot, they had to get a 100% vote in support of their proposal. Ostensibly, this suggests a fetish of consensus that seeks to neutralize discord, rather than to mine generative forms from conflict that arise, ipso facto, from engaging with otherness. 100% consensus likely blocks out works that are divisive, exhibit a nuance of ambivalence, or operate strategies of transgression. Many of the works on display were conceptually ambitious, but otherwise, went down easy. It was hard to disagree with the Instituto de Artivismo Hannah Arendt who believe Cuban artists should fight for free speech, or with the Wajukuu Art Project who believe artists from the slums of Nairobi should have opportunities to make art.

But to lament a lack of nuance — possibly the ultimate bourgeois pleasure — is to impose aesthetic judgment, which the exhibition actively deprioritized. Aesthetics depends upon an experience of art split between object and spectator, which documenta fifteen categorically contests, down to the level of language. “Artwork” is outmoded. Instead, they say “initiative,” which describes an activity set in motion by an artist or collective, and may include activities that continue beyond the exhibition. Except ruangrupa doesn’t even like the word “exhibition.” Instead, they say “school,” in which the visitor participates not as a consumer of experiences, but as a student.

The Fridericianum, traditionally the heart of documenta, was renamed “Fridskul,” or the Fridericianum school. The concept was adapted from the Jakarta-based Gudskul collective — formed by ruangrupa, Serrum, and Grafis Huru Hara — which consists of eleven artists and collectives. Gudskul is something like a DIY think tank that collectively runs meetings to produce new ideas about collectivity. They call the results of a majelis a “harvest,” an artistic recording of the discussion. This can be as unconventional as a meme or a chess game, but it often takes the form of a diagram, many of which were on display at the Gudskul environment at Fridskul. One untitled banner tries to map out a theory of collective process, in which “friends making” is connected both as a resource for “collective sustainability” and a way to “explore the ecosystem.”

I attended the Gudskul meeting, expecting some kind of congress for the people’s liberation. From the outset, Gudskul and the audience were trying to answer questions about the definition of a collective. Except it was clear they weren’t getting anything done. They were having too much fun. They were laughing, playing rock paper scissors, and spinning a bicycle wheel formatted into a roulette to make decisions. While Gudskul may appear to borrow the structure of an elite Silicon Valley incubator, the practice appeared to be anything but. They were inefficient, circular, aimless, joyful. Ralph and Ness, two of the participants, told me that one resource shared in lumbung is humor, which energizes.

View of Fridskul Common Library, Fridericianum, Kassel, 2022. Photo: Victoria Tomaschko

Dan Perjovschi, Horizontal Newspaper (detail), 2022. Installation view, Rainer-Dierichs-Platz, Kassel, 2022. Photo: Frank Sperling

Asia Art Archive and K.G. Subramanyan, Buffalo and Rhino, c. 1960–80; Feroze Katpitia, Monkey, c. 1960–80); toys designed for the Fine Arts Fair. Installation view, Fridericianum, Kassel, 2022. Photo: Frank Sperling

Humor is one of the core values outlined in another mural-diagram that wraps the Fridericianum columns like chalk on a blackboard. “Generosity” is a model of abundance that intervenes upon the zero-sum logic of capitalism. “Sufficiency” declares an emphasis on sustainability over profit. In an exhibition that featured almost entirely works from the Global South, “Local Anchoring” is an argument that the meaning of an artwork should not be determined on aesthetic principles, but by its relevance in its social context or embodied ecosystem.

In Dwight MacDonald’s 1960 essay “Masscult and Midcult,” he described that before industrialism ushered in the rise of mass culture, there was only high art and folk art, a schema in which there was a clear suggestion of the supremacy of the modern over the primitive. Folk art was by untrained, outsider artists and rose to meet specific needs of the community without awareness of art history, much less the avant-garde. But if ruangrupa’s documenta has one argument, it would be to trouble that distinction, proposing the supremacy of folk art over high art, which is merely cultivated and enjoyed by an elite class and rendered effectively neutered. Not only is folk art positioned as a legitimate response to imperialism, the emphasis of folk art, often considered formally unsophisticated, contests the progressive conception of art history as successive strategies up-staging each other along a linear chronology. But since methodological strategies are historically contingent, how to consider them from localities with histories different than the West’s?

For instance, what did it mean to display a film presented by Komîna Fîlm a Rojava collective that documented traditional Kurdish singing, almost entirely unchanged from antiquity? In interviews, singers repeat platitudes one after another: “How will we build love if art isn’t in our hearts?” Or “the decay of this art means the defeat of humanity.” Let’s just say you wouldn’t get away with this at the Städelschule. But within the Kurdish context of vanishing archives, Turkish censorship, and ongoing genocide against a nomadic race without a nation state, the meaning and value of traditional song becomes contemporaneously renewed with enormously high political stakes.

Taring Padi, Sekarang Mereka, Besok Kita (Today they’ve come for them, tomorrow they come for us), 2021. Installation view, Hallenbad Ost, Kassel, 2022. Photo: Frank Sperling

The most prominently displayed folk artists in the exhibition was the Taring Padi collective from Yogyakarta. On the wall of the Taring Padi exhibition that took over the entire Hallenbad-Ost, hand-written script in gold reads, “Taring Padi’s overall theme for documenta fifteen is Bara Solidaritas: Sekarang Mereka Besok Kita (the Flame of Solidarity: First they came for them, then they came for us).” One painting displays a nude Black woman breaking free from chains beneath the words, “Refuse to be a victim.”

This was agitprop that sought solidarity with the oppressed people of the world. At the southeast end of Friedrichsplatz, the historic square at the front of the Fridericianum, People’s Justice (2002), a massive, collectively painted banner, eighteen-meters wide, by Taring Padi hung from a scaffold, overlooking a sea of life-size cardboard puppets anchored into the ground, invoking traditional wayang, or shadow puppets, from tenth century Indonesia. As explicitly anti-capitalist, these works were not made for the gallery, but to be used as props for anti-capitalist protests, carnivals, and musical performances.

These were not artists who cared about how the materiality of images might be informed by their circulation in the metaverse. They’re trying to get free.

“The shadow puppets are a very rural, very traditional form of art making,” a friend of mine and scholar of Indonesian art collectives said. “The Communist Party’s official writings in the 1950s and 1960s said that a people’s culture should use forms made by the people. You should not try to make fine art oil paintings, you should do wayang shows that can communicate the revolutionary message to the rural Communist Party.”

Whether this was avant-garde was an irrelevant — somehow gauche and philistine — question. These were not artists who cared about how the materiality of images might be informed by their circulation in the metaverse. They’re trying to get free.

On the upper left of the banner, Suharto, head of the thirty-two-year-long military dictatorship, sits in a regal suit beneath a blood red sky, over an army of tanks and soldiers. Beneath them, dozens of skulls spill into mass graves, referencing the anti-Communist genocide of 1965 — imagery that would have been censored during the military regime. Soldiers depicted with pig noses and ears represent the alliance between Suharto’s military regime and corporate capitalism, which led to the 1997 Asian financial crisis. On the right, workers and students hold picket signs, alluding to the bloody student uprising of the 1990s against the Suharto regime. Still, leisure is positioned as indispensable to the fight against capitalism: children are dancing, protesters are cooking.

On the level of organizing bodies across flat space, the banner was a tour-de-force in figurative composition. Hundreds of figures appear, so it was easy to overlook the man in the brown suit near the center left of the banner, wearing a bowler hat with SS insignia. In fact, ruangrupa claims they didn’t notice him. I didn’t notice him.

Just a few days after the banner was exhibited, people started flagging images of the banner on social media as antisemitic, prompting the attention of German and Israeli politicians. At the behest of Kassel’s mayor, a black cloak was placed over People’s Justice, which hovered ominously over the Platz. Taring Padi declared it a “monument of mourning for the impossibility of dialogue at this moment.”

Texts messages flew. Germans reading the German press relayed the news to the Americans. When Pujan showed me a screenshot of the drawing on Twitter, it looked like caricature that fully understood its history: a man with bloodshot eyes, large nose, and pig ears bares his fangs with his snake tongue slithering out. Long sidelocks beneath his helmet identify him as an Orthodox Jew. The Israeli Embassy to Germany described it as, “reminiscent of propaganda used by Goebbels and his goons during darker times in German history.”

The German federal culture minister said: “The removal of this mural, which shows clearly antisemitic pictorial elements, is overdue. The mere covering up and the statement by the Taring Padi artist collective on the matter were absolutely unacceptable.”

Soon, the banner was dismantled entirely.

Happening in real time was a morality tale about the unholy alliance between art and geopolitics, the scarcity of territoriality in all facets of life, and the naked truth, from the playground to the Gaza Strip, that conflict is an irreducible part of human relations.

The night that People’s Justice was being taken down, a small crowd gathered at the site in protest, in mourning. Policemen with guns and uniform patrolled the Platz. Officers audited the exhibition, taking pictures of each work for more potential antisemitism.

When some friends and I arrived at the dismantling site, protesters shouted “Free Palestine!” in German. The cardboard puppets had been uprooted. Some were destroyed and tossed on the floor in piles, like faggots prepared for the burning. It was lost on no one that this was the location where, in 1933, over two-thousand books were burned by the Nazi regime. Others wandered the grounds, glassy-eyed and confused. Some documenta artists organized to salvage some of the puppets and place it beside their exhibited works in solidarity.

In a text, Paige said, “I can’t help but be deeply apprehensive about how an exhibition that is so clearly about bringing and sharing contexts from elsewhere also failed to take as seriously, as it should have, the context of where it was bringing all that to .”

Ryan asked, “So is this a competition of genocides now?”

“To leave that up and ask the people of Kassel to look at that ugly thing for 100 days. That’s asking a lot,” said Linn.

Solidarity does not, should not, and cannot require moral perfection.

By the grass, I saw a group of the Taring Padi artists sitting in a circle. I watched one artist drop a cigarette and snuff it on the grass with his shoe beneath a waning sunset. When a white, blue-eyed mourner came to give condolences, they seemed irritated. Standing against a Raphaelite pink sky, they looked dignified, silent, exiled. Crucially, they appeared to me not as martyrs, but tragic heroes: noble figures whose essential, human flaw brings them to ruin. Happening in real time was a morality tale about the unholy alliance between art and geopolitics, the scarcity of territoriality in all facets of life, and the naked truth, from the playground to the Gaza Strip, that conflict is an irreducible part of human relations.

One Taring Padi woodblock poster read, “Solidarity without borders,” which struck me as their admirable but tragic flaw. The thing about solidarity (and its power) is that it does not, should not, and cannot require moral perfection. It’s like friendship, one of the core goals of the lumbung practice: you can stand with a friend even if you know what they did was wrong. Which is the inalienable flaw of solidarity: the essential non-innocence of humanity.

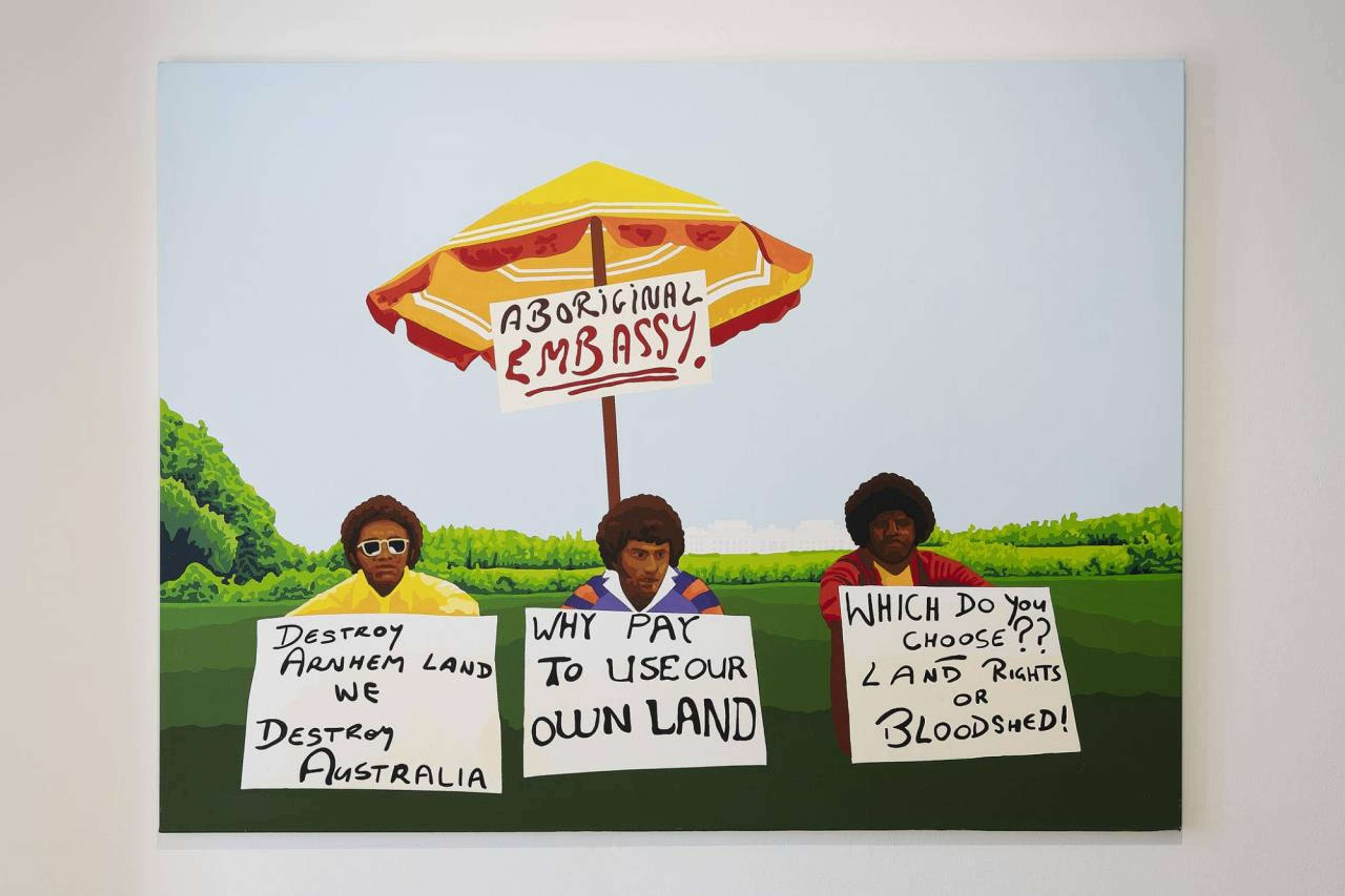

Richard Bell, Umbrella Embassy, 2022. Installation view, Fridericianum, Kassel, 2022. Photo: Nicolas Wefers

The Black Archives, Black Pasts & Presents: Interwoven Histories of Solidarity, 2022. Installation view, Fridericianum, Kassel, 2022. Photo: Frank Sperling

Against the censorship of art, I stand in solidarity with Taring Padi, even as I consider the drawing to be antisemitic. Yet it's hard to imagine a scenario where documenta could leave the work up in a country with adamantine laws against antisemitic speech. To be clear, this incident is different from removing an offensive work in an American context of cancel culture, which emerges as a kind of populist, vigilante justice when institutions are perceived as compromised or asleep. To support leaving the banner up at documenta would have been to stand against the law, a task that should be taken with fear and trembling.

But to cede ground to censorship — which ruangrupa did in their official statement — would be to allow the supplanting of politics over art, which drives a stake into the heart of the documenta project, back to its first edition when Arnold Bode exhibited art repressed by the Nazi regime. While art is always yoked to politics, it is distinct from politics. It can hold contradictions where politics cannot. In fact, tragedy resonates in the cultural imagination because it supposes that human vitality lies in a hero’s ability to hold multiple opposing forces at once. This aligns art, not politics, closer to the human. Its meaning can be indeterminate. It doesn’t need to obey the rules. It often fails.

___

documenta fifteen

Various sites, Kassel

18 Jun – 25 Sep 2022