Two years into a full-scale invasion, and almost a decade after the war with Russia began, Kyiv has settled into an exceptional version of normalcy. The city, which was besieged in 2022, is still subject to missile attacks: The air-raid sirens wail at least twice a day. People know that Russian MiG takeoffs are little reason for worry, whereas ballistic missiles are serious, a companion from Kyiv informs me, as we hurry to a metro station in the city’s medieval center after dinner one night in late January.

The stations are dug so deep that each escalator ride is itself a journey. In Soviet times, they were planned to provide shelter from nuclear attacks. Most are decked out in marble slabs like sombre church naves, some with vaults covered in glazed tiles, others in mosaics. The crowds speak in hushed voices. During alarms, people get coffee in small stores that also sell organic trail mix, flowers, and magazines, but no newspapers. School classes sit on folding chairs, doing homework, while recruits in uniform get on and off the trains, which remain in service. Young men in sneakers and sweatpants carry black or camouflage tactical shoulder bags, suggesting recent or upcoming trips to the front. They could all be soldiers soon.

Interiors of a Kyiv metro station, 2024. Photos: Avedis Hadjian

“Full-scale invasion” has become the established term for what began on 24 February 2022: “Kyiv under fire,” wrote photographer and author Yevgenia Belorusets in her War Diary (2023), “abandoned by the whole world, which is ready to sacrifice Ukraine in the hope that it will feed and satiate the aggressor for a while.” Followed in quick succession by the siege of the capital, massacres in Bucha and elsewhere, and the Ukrainian army’s unexpected resistance, the invasion has mainly become a grinding war of attrition in the East, while missile and drone attacks continue throughout the country. Early one morning, the sound of detonations wakes me in my hotel room. That day, over forty missiles are fired towards Kyiv, roughly half of which are intercepted. Eighteen people are killed in airstrikes across the country.

Almost a decade prior, then-president Yanukovych sought closer ties with Russia. Protests, which became know as the Revolution of Dignity ousted him and kindled a feeling of political agency among the young. Shortly thereafter, Putin’s Russia began battling the chimera of a liberal culture, allegedly allied with the West, even as segments of the North Atlantic public have abandoned democratic values for nationalist nostalgia.

If the 2014 invasion of Crimea and the sham referendums that brought Donetsk and Luhansk, under Russian control inaugurated a new present, the 2022 invasion, coinciding with the end of the COVID pandemic, brought forth slippery jargon intended to make sense of the long contemporary: the new normal, the vibe shift, the revenge of the real. Global supply chains were outed as fragile; pandemics and political crises, contagious. Most compelling is the notion of polycrisis, used to describe this tangle: The Russian attack caused higher food and energy prices, inflaming the rise of far-right parties across Europe sympathetic to Putin’s regime, and the risk of nuclear escalation. As the philosopher Benjamin Bratton cautions: “To assume that the future will be like the present – only more so – is a risky bet.”

A plaza in Kyiv, 2024. Photo: Avedis Hadjian

Covered artworks at the Khanenko Museum, Kyiv, 2024. Photos: Philipp Hindahl

Meanwhile, in Kyiv, time is squeezed into the short spans between the sirens. Over orange wine, after a gallery opening, I talk to a programmer who mainly works with US clients. He likes to live unbound by material possessions, he tells me, so he can pack his things into two duffle bags and leave at any time. He describes this like a digital nomad, but, in Kyiv, I get the feeling that perpetual readiness is hardly a lifestyle choice. Even when the war is not named, it is omnipresent. At a reading in Berlin in mid-January, Belorusets speaks about cumulative exhaustion among Ukrainians, deprived of peaceful sleep by shelling. In the beginning, she said, she couldn’t imagine how a war starts. Now, it’s difficult to picture this one’s end.

For the artist Nikita Kadan, the warping of macro time has not yet disappeared from the war’s prehistory, even if the invasion has tended to reduce complexity. During a visit to his studio on the ninth floor of an apartment building in Kyiv’s Shuliavka district, Kadan speaks about the orphans of Ukrainian historiography, the objects, artworks, and monuments that fit comfortably into neither the old Soviet stories, nor the newer ones of Ukrainian national independence. Kadan has reconstructed two 20s-era Cubo-futurist monuments by Ivan Kavaleridse, one to a communist leader in Bakhmut destroyed by Nazi occupiers, the other to the romantic poet Taras Shevchenko in Poltava, as part of the series The Red Mountains (2019). Absent the originals’ heroic figures, the crystalline geological formations of the reconstructed plinths turns into cubist monuments in their own right, perhaps locating a stripped-down modernism unbroken by Stalin’s persecution of artists. There were generations of talented people who had little access to art beyond the borders of the Soviet Union. “We had the development of the avant-garde,” says Kadan, “and then it was violently, brutally cut.”

Nikita Kadan, Red Mountains, 2019. Installation view, mumok, Vienna, 2019. © mumok. Courtesy: the artist. Photos: Klaus Pichler

Looking back at the Soviet Union, Russia is increasingly described as a colonizing power, a pushback against the old propaganda story of the anti-imperialist empire. The latest act of decolonization, wrote the filmmaker Oleksyi Radynski in 2023, started with the crumbling of the USSR in 1991, which had been “nothing but a slightly modernized Russian Empire.” As the war presents the discursive danger of nationalist simplification and canceling Russian cultural imperialism, Kadan is advocating for nuance, deconstruction, and alternative timelines. “I believe that we can reclaim some part of the common heritage with the colonizer because many Ukrainian artworks and people have been claimed to be Russian art and culture: Russian modernism,” says Kadan. “We can act less with the national conservative attitude which demands to cut off your hand when it is infected by the culture of empire, lest it infects your entire body.”

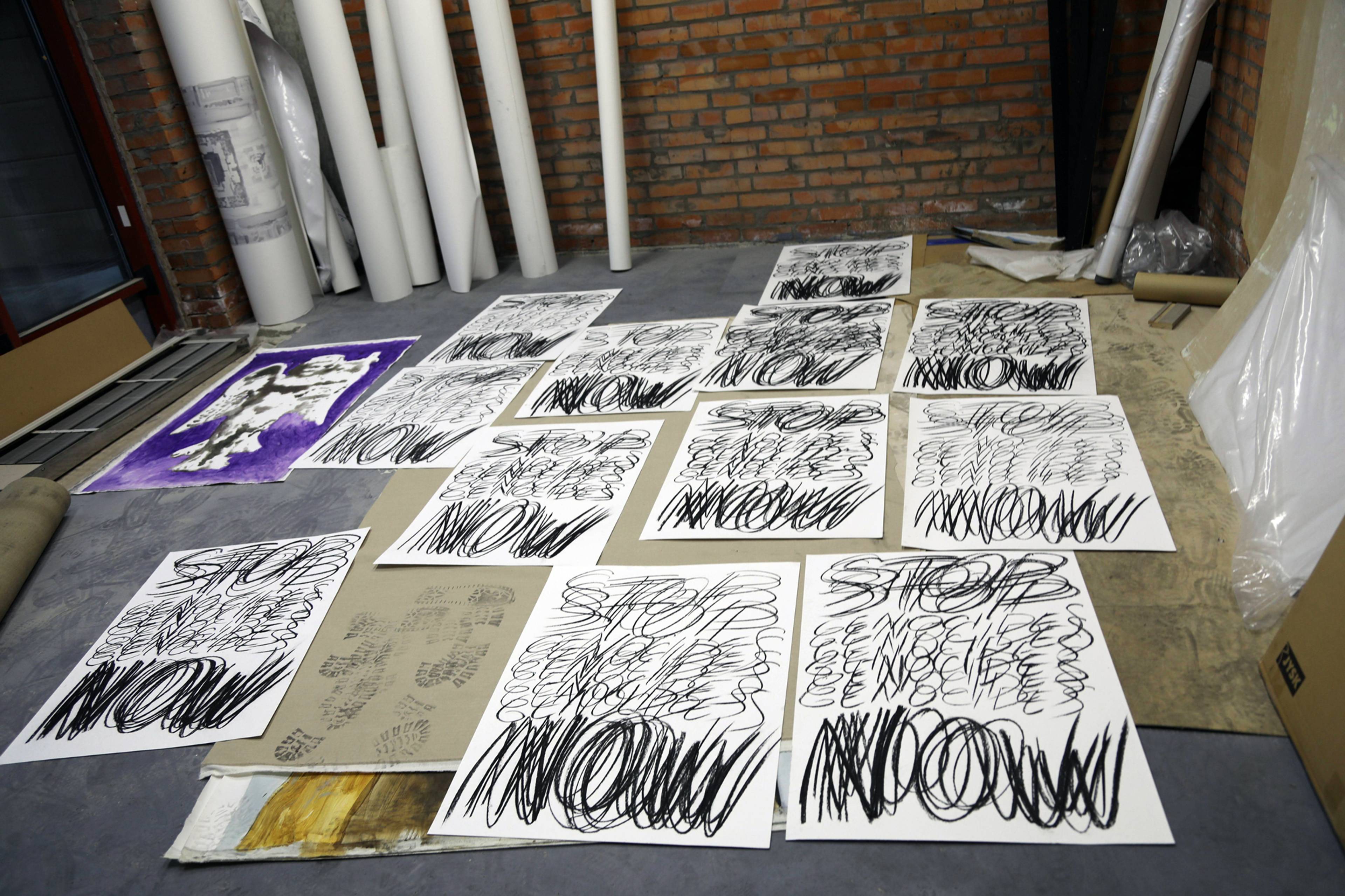

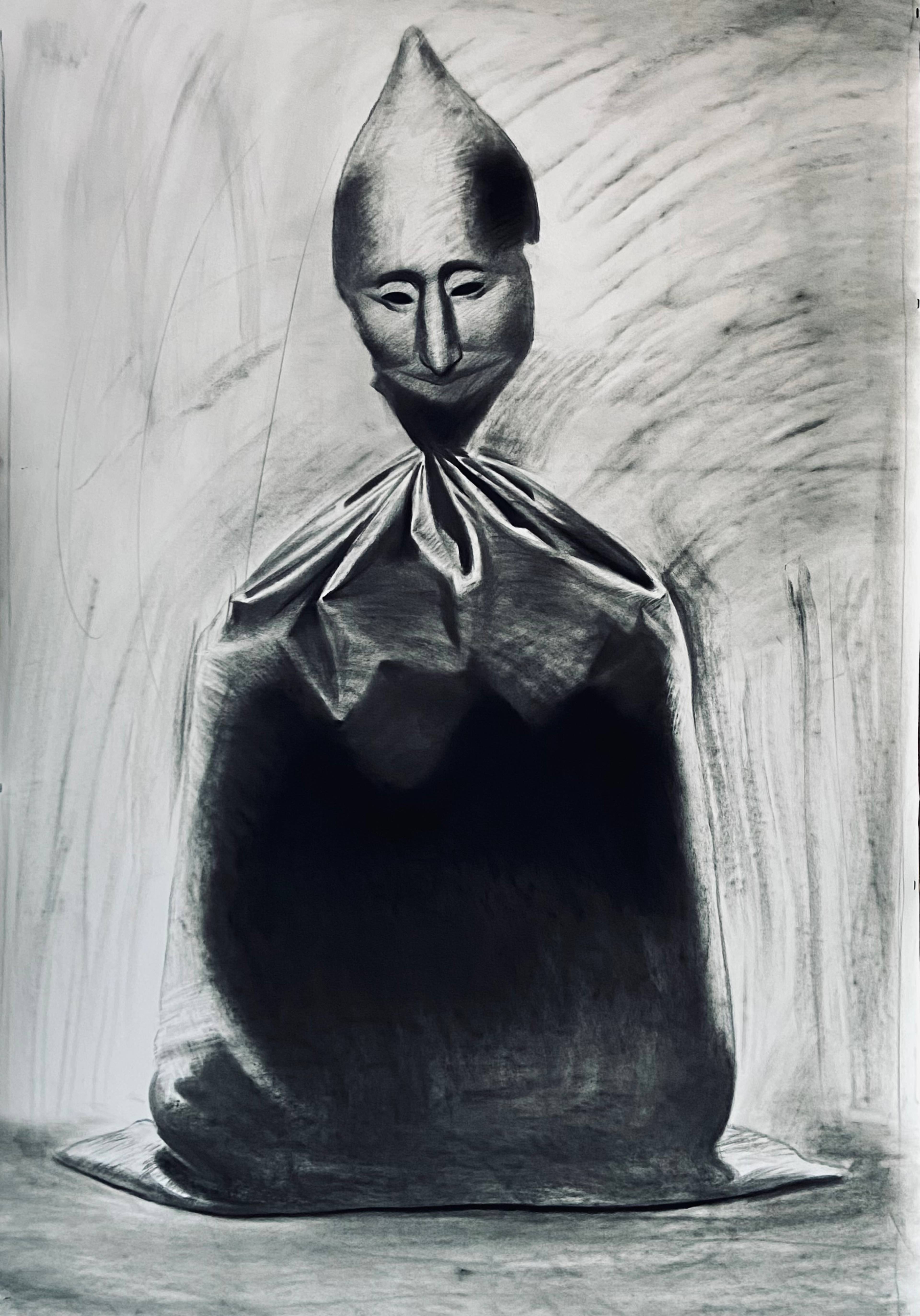

Before we leave, Kadan talks about the likelihood of a further escalation of this war, then apologizes for being such a Cassandra. I say, he’d only be a Cassandra if nobody believed him. The joke falls flat. Later, I notice that one image from a series of large-scale charcoal drawings pinned to the studio wall shows the golden mask of the Mycenaean King Agamemnon, who, at the end of the Trojan War, abducted Cassandra. In the drawing, the mask seems to hover over a black trash bag.

Works in Nikita Kadan’s studio, Kyiv, 2024. Photos: Avedis Hadjian

Drawing in Nikita Kadan’s studio, Kyiv, 2024. Coutesy: the artist

The news in Kyiv are gloomy, and have been for a while. The counteroffensive has stalled; reserves and morale are running low; prospects of further military aid from Washington, D.C. are fading. People speak about the impending reelection of former US president and fawning Putin admirer Donald Trump, and its consequences for Ukraine and Europe. The city’s art scene is not without glimmers of hope: I meet artists and curators involved in the Kyiv Biennial, spread out among eight cities in and beyond Ukraine; others planning a comprehensive archive of contemporary art that will lead to the creation of a new museum; and more still who are making use of Mystetskyi Arsenal, a vast, 18th-century exhibition space that has been a viable institution of contemporary art for well over a decade. But it is palpable how precarious this freedom in Ukraine is.

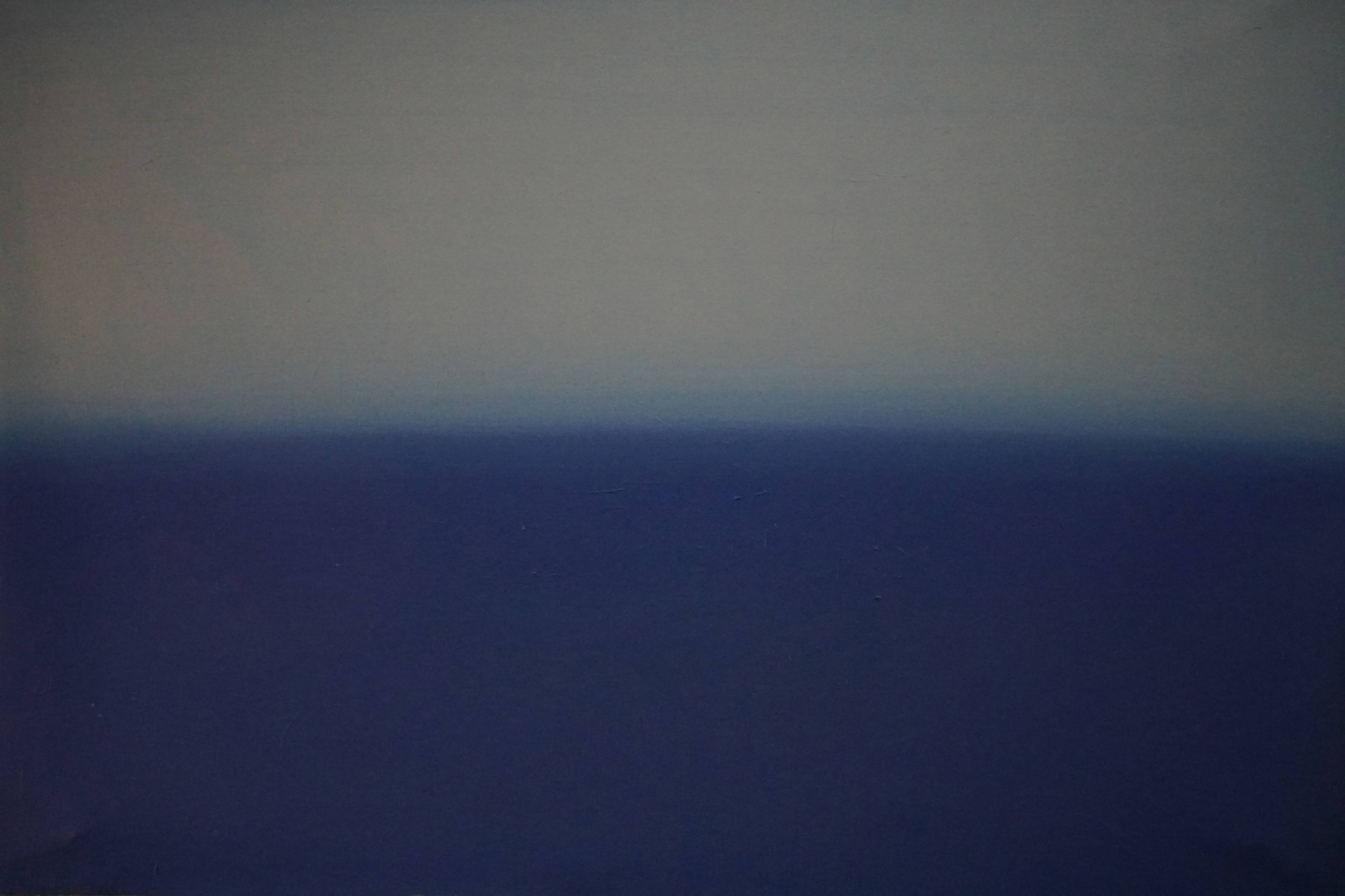

At the Institute of Automatics, an abandoned, Soviet-era research facility which now houses artists’ studios, the wood-paneled corridors are cold, and it smells of oil paint. “This is where the missiles were designed that are now being dropped on us,” someone jokes one night. Anton Saenko, a painter who works in the old building, has stripped his landscapes down over the years, until all that remains is a blurred line which separates sky and land, not unlike the Ukrainian flag, albeit in a much earthier palette. One of these emptied-out paintings, which he calls “liberated landscapes,” reads “The horizon is burning” in minuscule, sans-serif Ukrainian, as if war has become part of the landscape itself. “The landscape is always political,” says Saenko.

Institute of Automatics, Kyiv, 2024. Photo: Philipp Hindahl

Anton Saenko’s studio, Institute of Automatics, Kyiv, 2024. Photo: Philipp Hindahl

Anton Saenko in his studio, Kyiv. Photo: Avedis Hadjian

Anton Saenko, Horizon 3, 2023, oil on canvas, 60 x 80 cm. Courtesy: the artist

Saenko’s apparently metaphysical pictures have a correlate in material reality, too. Far away from the relative safety of Kyiv, people lead endangered lives within shelled and charred terrain. The word chernozem – literally “black earth” – is the geological term for the nutrient-rich soil in southern and eastern Ukraine that made the country such an important producer of grain. As the war draws on, it becomes clear that the term has acquired a second meaning, as the earth becomes a carrier of the war’s memory.

Back in Berlin, I watch a montage of drone footage, panning over craters that perforate fields and CGI animations of thriving forests. In her voiceover, the artist Katya Buchatska suggests planting a tree in each crater to record the injuries to the earth and to create a living memorial of “people, ecosystems, landscape, harvest, soil,” one that would not glorify the past, but would prevent the erasure of history in the future.

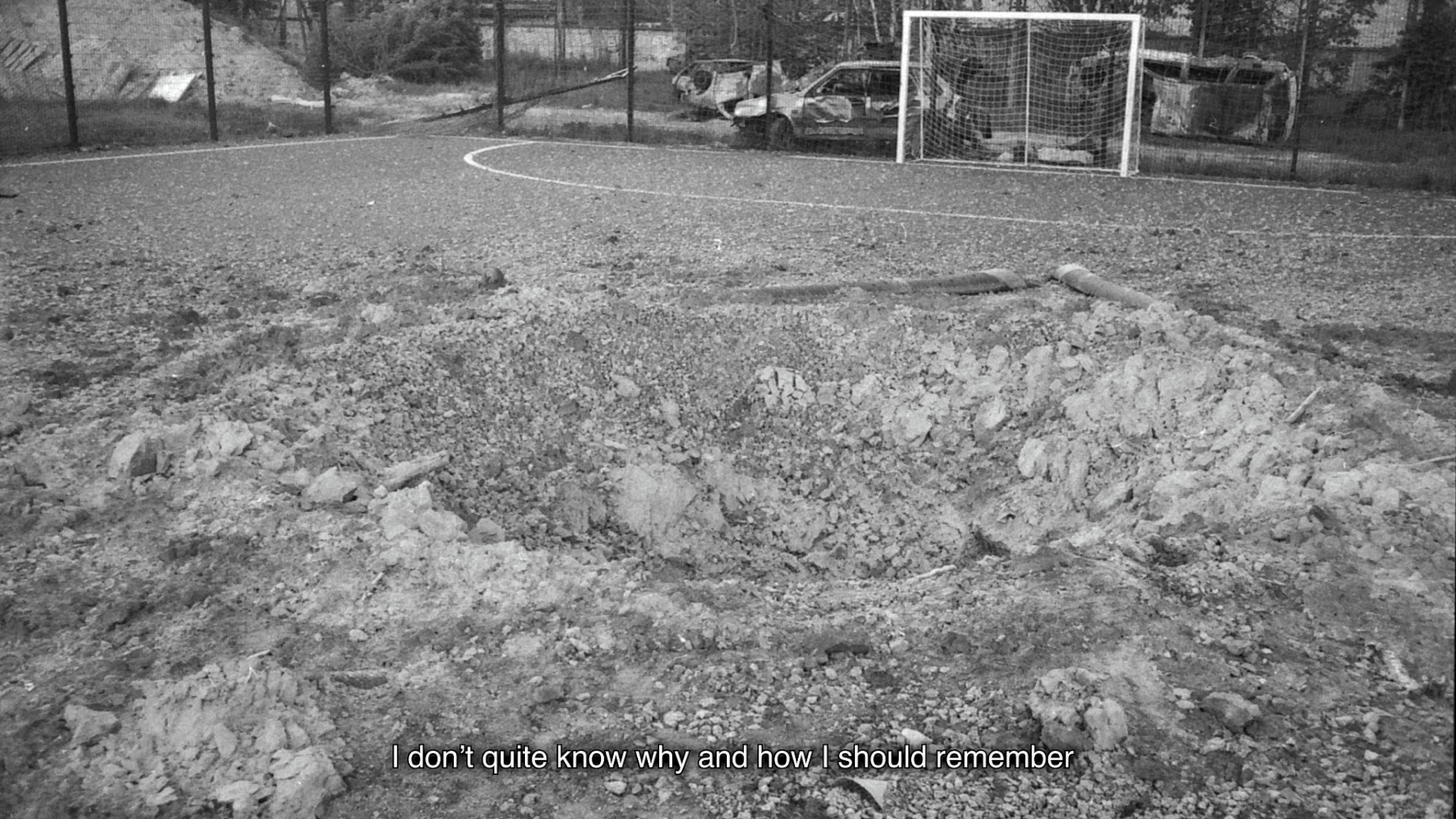

Stills from Katya Buchatska, This World Is Recording, 2023, 7 min. Courtesy: the artist

The video was created as part of an artistic research lab on war experiences organized by culture memory platform Past/Future/Art, which originally formed to work with the memory of tragedies – among them the famines of the 1930s (known in Ukraine as the Holodomor), the Holocaust, and the Chernobyl disaster – using instruments of art. One of its co-founders, the curator Kateryna Semenyuk, tells me over video call that it’s commonly suggested that trauma can only be dealt with at a distance. But faced in the early days of full-scale invasion with questions like “What to do with this memory?” and “What do we have to preserve?” the project tasked itself with the near-impossible: to memorialize events as they happen.

“It is enough to see the wounded land to feel the pain,” says Semenyuk. Buchatska’s video is not a memorial, but a tentative meditation on what memorials should do, or perhaps how they can be: more like a communal garden, something to be cared for. “In order to answer who we are, we appeal to the past,” the artist’s voiceover intones. It may be risky to bet on the future, but the extended present leaves hardly any other choice. At the end of 2023, Belorusets wrote that documenting the war seems pointless at a moment when no end is in sight, when it has become normalcy. Buried within is an unanswerable question about what any artistic endeavor can contribute in a war – a complication of historical certainties, a more seamless idea of identity – but Buchatska finds a different answer in her video’s title: This World is Recording.

Monument to the Mother of Alevtina Kakhidze, 2021, Muzychi, the Kyiv region. Courtesy: Past / Future / Art. Photo: Marho Didichenko

Memorial to victims of war, Kyiv. Photo: Avedis Hadjia

___