Even before the U.S. Supreme Court May 2023 decision on the status of Andy Warhol’s art with respect to American copyright protections, many in the art world seemed convinced that some sort of conceptual death was underway. The same majority of retrograde justices that overturned federal abortion protections in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, it seemed, were being asked to determine when, precisely, the act of artistic invention begins. Or, to put it in legalese: what constitutes “fair use?”

If the court ruled against the estate for Warhol’s work, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, and forced it to pay a licensing fee each time that another person’s art was used in his own, then the spirit of appropriation, so integral to the strategies of Pop Art and the Pictures Generation, might find its terminus, a death of technique at the tendrilous hands of the administrative state. If they ruled with the foundation, on the other hand, postmodernism might live to see another day, marking a judicial recognition that art is intrinsically additive, discursive, and referential. That nothing is new under the sun would be reaffirmed, and museums could hold onto the derivative works in their collections without fear of suffering retribution of intellectual property claims.

Faced with the actual 7:2 decision from 18 May against the Warhol foundation, the art world kvetchers don’t have extensive cause to mourn, at least, if they read the verdict’s fine print. Postmodernism isn’t dead – yet. In fact, with the rise of generative AI, the age of the simulacra might be just getting underway. Given the limited scope of the court’s ruling, it might be best understood not as incriminating some of the 20th century’s most iconic artworks, but as defending against a future where all authorship is swallowed by the digestive system of a quasi-sentient reproduction machine.

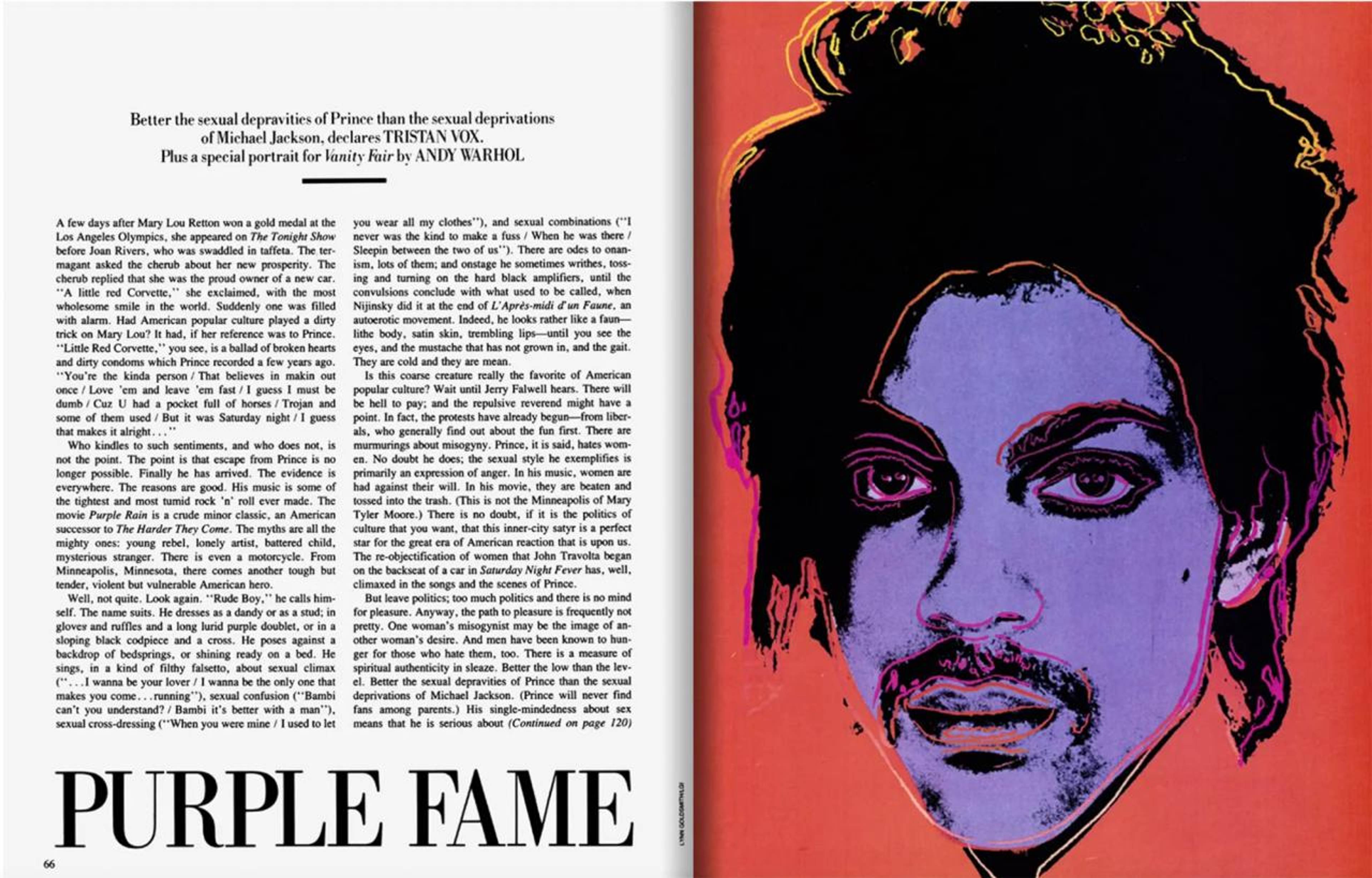

Spread from Vanity Fair, Tristan Vox, “Purple Fame,” November 1984

While the court case dates back to 2016, the underlying story begins in 1981, when celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith was commissioned by Newsweek Magazine to take a portrait of Prince. Several years on, around the 1984 release of Purple Rain, Vanity Fair commissioned Warhol to create an image to accompany the profile “Purple Fame.” Warhol chose to use Goldsmith’s photo as a starting point, with the magazine agreeing to pay her a $400 licensing fee and credit her work, which was to be used solely in connection with that single issue.

The “Prince Series,” which Warhol created between 1984 and his death in 1987, consisted of fifteen additional images that reference Goldsmith’s photograph. When Prince died in 2016, Vanity Fair ’s parent company, Condé Nast, published a special issue about his life and licensed a different image from the series, which went on the cover. It paid the Warhol foundation $10,250 to license the picture, while Goldsmith received neither money nor credit. Goldsmith objected, on the grounds that she had only licensed the photograph for one-time use, on the cover from 1984. The foundation sued her in response, asking the courts to rule that Warhol’s changes to the photograph were “transformative” and thus protected by fair use doctrine, which permits select usages of copyrighted works without the copyright owner’s permission. A district court agreed with the foundation, while an appeals court did not, setting the table for the Supreme Court’s finding in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith: that photographer’s “original works, like those of other photographers, are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists.”

But that’s not exactly what you think it means.

The matter of “transformation” is a tricky legal concept used in the federal judicial system to distinguish between works that are “original” and those that are merely copies. Judges rely on four criteria to evaluate whether an item merits fair-use protections: the purpose and character of the work; the nature of the work; the amount taken from the original work; and the effect of the new work on a potential market. Fair use laws protect everything from Twitter dunks and true-crime podcasts to civilian videos of acts of police brutality – basically, anything that can be understood as criticism, commentary, journalistic reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research.

Warhol’s Soup Cans series uses Campbell’s copyrighted work for an artistic commentary on consumerism, a purpose that is orthogonal to advertising soup.

When it comes to artistic creation, however, the concept is murkier. Is Marcel Duchamp’s drawing a mustache on a postcard of the Mona Lisa a sufficient “transformation” of the iconic painting? How about the work of photographer Sherrie Levine, who, in the 1980s, became famous for producing “pirated prints” – photographs of other people’s photographs, such as those of Walker Evans – which, as critic Rosalind Krauss argued “explicitly deconstructs the modernist notion of origin.”

In the court proceedings, this type of question was asked explicitly by the respective judges, who attempted to form a perspective using the commentary of experts, namely art critics and art historians. Liberal Justice Sotomayer, who wrote the case’s majority opinion against the foundation, inveighed that Warhol’s “Soup Cans series uses Campbell’s copyrighted work for an artistic commentary on consumerism, a purpose that is orthogonal to advertising soup.” Similarly, in reference to the Prince series, conservative Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., who was the lone justice to join Elena Kagan’s dissenting opinion, said that, while Goldsmith’s photo simply presents Prince’s appearance, Warhol’s painting “sends a message about the depersonalization of modern culture and celebrity status.”

While the decision, on its surface, appears to be a judgment against the foundations of appropriation art – since it ruled that the Warhol Foundation didn’t have the right to use Goldsmith’s image in 2016 without paying her – the details of the decisions are more nuanced. A closer reading of the court’s thirty-nine-page decision shows that the real problem noted by the majority was the Warhol Foundation’s failure to pay Goldsmith a licensing fee in 2016 for the use of a second image in Vanity Fair, not the originality of the art in general. In the decision, the justices wrote that “The Court expresses no opinion as to the creation, display, or sale of any of the original Prince Series works.”

Effectively, the Supreme Court sidestepped the larger issue of whether Warhol should have used Goldsmith’s image in the first place. It punted the matter of “originality” and “transformation” indefinitely down the road, when the hairy problem of crediting and compensating original authorship will become unavoidable.

And that reckoning is unavoidable. Looming in the background of this case – out of sight, but none too far out of focus – is another issue that’s quickly beginning to creep up court dockets across the US: namely, rules adjudicating the use of generative AI. With the emergence of tools like ChatGPT and Midjourney – which suck in media from everywhere to produce endless streams of uncanny riffs and spin-offs, and duplicates – the idea of copyright as we know it – the notion that some things are distinct and original – is becoming intrinsically uncertain. Given a machine that could, for example, produce a catalog of every potential melody and chord change, then immediately attempt to patent each composition, there are potential futures where it becomes impossible for musicians to create work without violating those ownership protections. And while this might not happen in practice, the fact that it could presents a thorn in the side of authorship, both in legal and artistic communities.

Those scenarios are very likely what the courts have in mind. While the US Copyright Office has already determined that art created solely by AI isn’t eligible for copyright protection without proof of significant “human authorship,” what’s still unclear is how intellectual property holders of all types (artists, coders, musicians, writers, etc.) will be compensated for media that end up in AI models.

When everything is a potential data point, it becomes nearly impossible to distinguish what, exactly, derives from what, and to what extent that derivation has occurred.

Currently, there are multiple court cases in the US litigating this problem, including proceedings related to a single suit against Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, and DeviantArt, in which a trio of artists is claiming that the tools are scraping their work without permission. In April, all three companies filed a motion to dismiss, claiming that the images generated by these AI systems bear little resemblance to the works they’re trained on and that the artists didn’t specify which works were used.

And that’s exactly the point. When everything is a potential data point, it becomes nearly impossible to distinguish what, exactly, derives from what, and to what extent that derivation has occurred. Imagine, for example, that Midjourney attempted to figure out the percentage of an AI-generated image derived from a specific work, given the billions of inputs its software is trained on. To what extent does being “trained” on an image translate into the production of new ones? And how does that connect to revenue, and, by extension, the amount owed to artists? (Especially given that many of the companies producing AI-generated media don’t currently make any profits).

For obvious reasons, these are problems that existing copyright laws were not written to solve. If the legal system is going to defend itself and the intellectual property-holders it purports to serve from owners of technologies capable of subverting the foundations of the current copyright regime, it will need to draw upon precedent, according to which smaller fish are paid by bigger fish for riffing on, and reproducing, their work, especially in commercial contexts. The ruling against the Warhol Foundation isn’t an attack on the creative process, but part of a wider effort to entrench the integrity of the copyright system, and to compensate creators for their role in producing referential work.

While this may affect some artists in the short term – causing them to think twice before they use someone else’s material in a licensing context – this case should be understood as part of the looming battle against the real antagonists: the technologists who want to swallow the world whole.

___