1. The Jianghu of Diaspora

What happens when art becomes a portal into a radically different mode of relation? More enduring than the flimsy relational aesthetics of Nicolas Bourriaud, and more ancient than the aspirational merging of art and life by Western modernism’s various avant-gardes.

A vital sociality inextricable from the dirty, ad-hoc, pulsing, cacophonous immigrant spaces around us, those of us who grew up too poor and irrelevant to be touched by the cold sterility of elite institutions. What Foucault might call a “heterotopia,” a space of otherness; what I call the stateless, borderless, watery world of jianghu (江湖), the jianghu of diaspora.

In Chinese martial arts tales, the jianghu (rivers and lakes) is an amorphous, lawless realm, often counterposed against the elite sphere of chaoting (the royal court), just as the grassroots minjian (folk culture) offers a bottom-up alternative to tianxia (all under heaven). Lively, local, colorful, unofficial, full of heat and noise, chaos and fate, jianghu is part of a collective imagining, millennia in the making, of a fluid social world outside state governance.

In the Warring States period (453–221 BCE), the philosopher Zhuangzi wrote:

“When the springs dry up and the fish are left stranded on the ground, they spew each other with moisture and wet each other down with spit – but it would be much better if they could forget each other in the rivers and lake [jianghu].”

Still from Wong Kar-wai, Happy Together, 1997, 96 min.

In Street Criers: A Cultural History of Chinese Beggars (2005), historian Hanchao Lu describes the jianghu as a world populated not by martial arts heroes, but by vagrants on the margins of society, unwanted, unloved – but free.

In an interview about his 2018 film Ash Is Purest White, titled “children of the jianghu” in Chinese, director Jia Zhangke describes the experience of being on the jianghu as “a group of people who leave home and, as they wander about, seek out life’s possibilities and search for a new home they can feel emotionally connected to.”

闯江湖 – to make a living on the jianghu

江湖恩怨 – debts and grievances on the jianghu

江湖再见 – to meet again on the jianghu

These vernacular expressions evoke an ancient social world, of dazzling enchantments and intense passions, infinitely rich, breathtakingly vast, prismatically imprinted in my young mind, in a small Hubei mountain town in the early 1990s, as I listened to stories on my yeye’s lap or watched wuxia dramas on TV: 西游记, 水浒传, 白蛇传, and others I can no longer name. Their sights and sounds, sensations and sentiments still run lush within me now, writing in the 2020s in a different language, in Brooklyn, New York.

Still from Stephen Chow, A Chinese Odyssey Part Two, 1995, 87 min.

2. From the Boat to the Mini-Mall

The jianghu is full of wanderers, withdrawn from official duty and public life: rootless souls like ours, lightly flung across the earth.

To the edges of the sky (天涯),

the corners of the sea (海角),

to meet again in other lifetimes, other countries – in a bamboo forest or a subway station, a deserted mountain path or a crowded immigrant mall.

Artist Lu Zhang’s participatory art project Wildman Clab (2018–21) draws out these fatefully coincidental encounters among jianghu wanderers, tracing the peripatetic routes of this watery world from ancient China to the diasporic spaces of our present.

The happenings of Wildman Clab included staged social situations that sprang up across New York’s Chinese immigrant spaces: a karaoke session in Columbus Park, attracting a group of seniors who regularly exercise there; a “boat date” in Sunset Park that revives Legend of the White Snake (白蛇傳), a famous Chinese folktale that dates back to the 12th century. In the exquisite West Lake scene, the white snake spirit, having transformed into a beautiful woman after a thousand years of self-cultivation, falls in love with a Confucian scholar, her savior from a previous life, drawn into the potency of their karmic pull.

Still from Lu Zhang, Karaoke at Columbus Park, Wildman CLAB, 2017, HD Video, sound, 7:21 min.

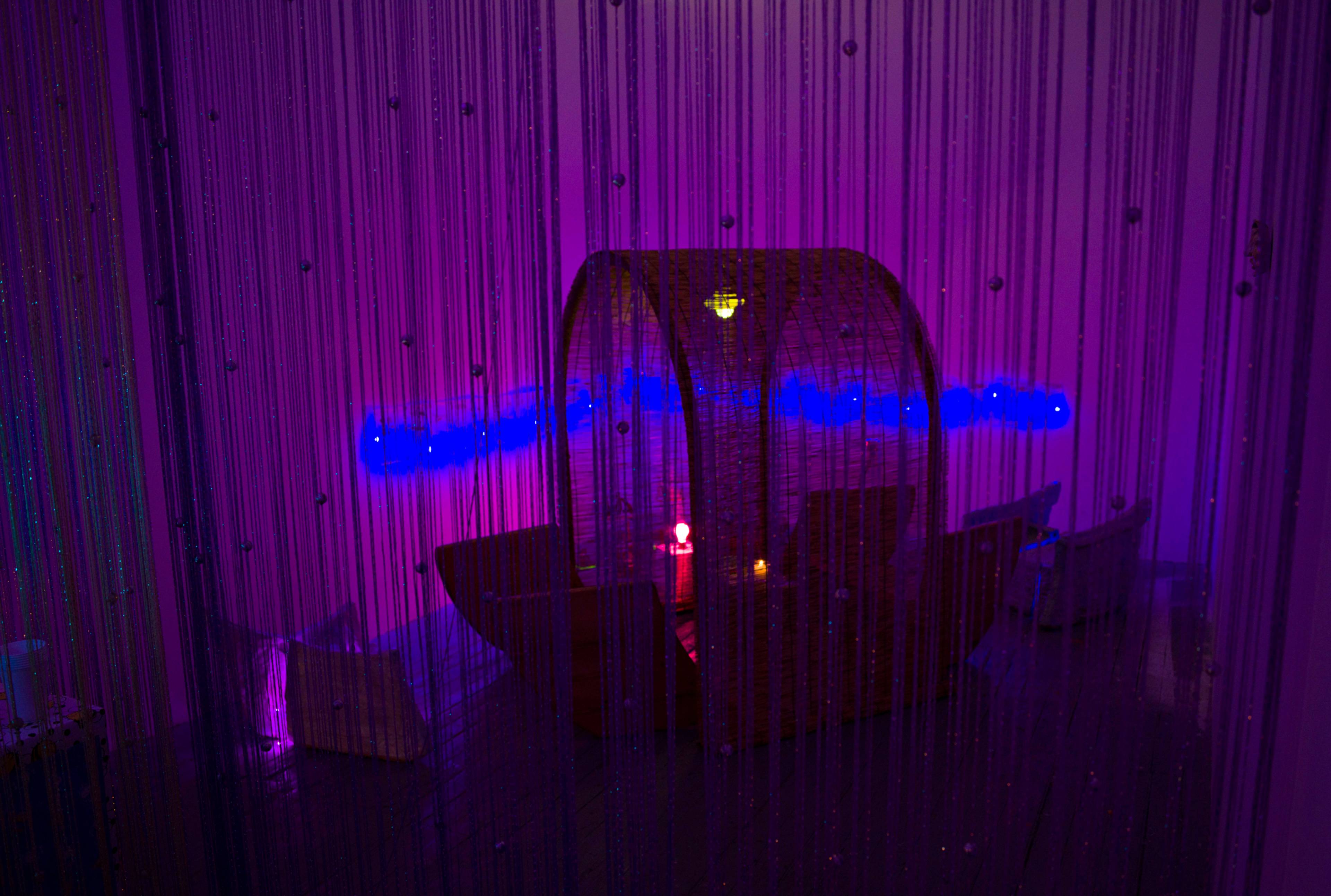

The interactive artwork Boat Date (2018) transports participants to that fateful boat ride on West Lake. We encounter each other inside the river boat installation, held by the artwork’s logic of yuanfen (缘分), that paradoxical concept of “fateful coincidence” or “predestined chance.” We play Chinese checkers behind crystal curtains, surrounded by ceramic river creatures and a rice paper sunset. Cantopop plays – lyrics half intimate, half indecipherable.

Were we destined to meet by chance?

十年修得同船渡, 百年修得共枕眠。

If, as the legend goes, it takes ten years to ride the same boat, and a hundred years to sleep on the same pillow, how many border-crossings, how many translations, how many identities lived and shed, before we can arrive at a common language again?

On the jianghu, roots grow in flowing water rather than still soil, a mode of homemaking for the homeless.

One character tells another in Ash Is Purest White: “Wherever there are people, there is jianghu.”

Lu Zhang, It Takes Ten Years Practice to be on the Same Boat, 2018. Installation view, Nars Foundation, New York

So, the jianghu crosses borders and screens: to Taipei’s ghostly Fu-Ho Theater in Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye Dragon Inn (2003); the dilapidated Buenos Aires walk-up where Tony Leung and Leslie Cheung play out their tortured romance in Wong Kar-wai’s Happy Together (1997); the apocalyptic New York of Ling Ma’s novel Severance (2018); the dim sum hall on the third floor of Flushing’s New World Mall, in the spring of 2021, as the pandemic thawed, where I attended a screening of Lu Zhang’s essay film A Girl Sings Along Without Knowing the Words (2021).

Titled after a line from Mei-mei Berssenbrugge poem “Dressing Up Our Pets” (1999), the thirty-minute film hypnotically circles the local spaces of Flushing, lulling us into a stream of impressions: mini-malls crammed with eclectic, colorful stalls; a group of evening dancers arcing their arms under the glow of a neon sign; empty lots and scaffolded buildings awaiting new development.

The bilingual narration layers over daily sights of Flushing life: the congested sidewalks of Main Street; stacks of bamboo steamers at a food stand; the red lantern interior of a supermarket. Zhang’s camera drifts with the flow of the crowd, catching little moments of intimacy, desire, and wonder. A figure in a yellow raincoat peeks into a char-siu restaurant one misty afternoon; a man naps inside a ceramics store; a grandmother and child amble along with arms linked. The artist herself appears as one of these local characters, taking lessons from a violin maker in the basement of one of the mini-malls that serve as the film’s central obsession.

During the dim sum hall screening, Zhang’s film exceeds the screen. The moving images dance along the wall, wrap around the pillars of the restaurant, land briefly on the bodies of the servers rushing by, interacting and merging with the chatter and bustle of the mall where my mother gets her groceries, my mother who has never set foot inside an art gallery.

“Site-specificity,” a term that, like “relational aesthetics,” had become so wrung dry of meaning, suddenly took on new vibrancy.

Bathed in the familiar sounds and smells of my immigrant years, the dream spaces of my youth, I felt the fault lines of my life dissolve …

Lu Zhang, A Girl Sings Along Without Knowing the Words, 2021. Installation view, Royal Queen Dim Sum, New World mall, Flushing, New York

3. My Flushing

My own history of Flushing began in 2000, the year my mother and I left Guangzhou for New York, where my father waited for us with a used Subaru he bought for $2000 and a one-bedroom apartment in the East Bronx. On the weekends we’d take the Subaru across the Whitestone Bridge to Queens, parking always in the lot of the H Mart on Northern Boulevard because it was free.

We’d trek over to the Chinese section of Flushing, blend into the crowd along Main Street, cram our grocery cart with books from the Flushing Queens Library, discounted vegetables and fruits, containers of 叉烧肉 and 夫妻肺片, rented VHS tapes of the latest Chinese movies or TV series, often having to empty the cart multiple times to strategically restack everything, to make sure the books and tapes and meats didn’t bruise the delicate fruits or crack the eggs. When we got hungry, we’d stop at a tiny dumpling place on a side street: eight potstickers for two dollars and sometimes a bowl of hot soy milk.

One evening during that first year in America, my mother and I got lost in Flushing. My father had a habit of walking far ahead of us on the street, and we lost track of him. The neighborhood suddenly grew cold and menacing. Neither of us knew much English then. We wandered around the windy darkness, adrift among a sea of strange faces, trying to find our way back to the H Mart parking lot …

Still from Lu Zhang, A Girl Sings Along Without Knowing the Words, 2021, HD Video, sound, 29:37 min

Later, after I entered middle school, we all got cellphones and went to Flushing separately. I attended a cram school across the street from the dumpling shop, full of other immigrant Asian kids trying to be good, to live and breathe the standardized tests that held the key to cleaner, quieter, more orderly worlds we couldn’t quite imagine. Before and after class, my friends and I would hang out at the McDonald’s on Main Street, where we ordered items off the Dollar Menu and reenacted scenes from Mean Girls (2004), or read Sweet Valley Junior High books from the Flushing Library, or listened to CDs on our Walkman – My Chemical Romance or Green Day or Jay Chou or whatever else we’d downloaded from Limewire that week – as we waited for the bus back to the Bronx.

Later, two years into my elite private high school, as the SATs loomed, I refused to attend a Flushing cram school. I signed up for classes at Kaplan in midtown, taught by a white guy fresh out of college. The classes didn’t help, and after two failed attempts at a decent score, I finally let my parents sign me up for Chinese test prep.

Seven years later, after I began my PhD at Yale, I took the train back to New York one weekend to go to the basement food court of New World Mall, where I gorged on flavors nowhere to be found in New Haven.

Still from Lu Zhang, A Girl Sings Along Without Knowing the Words, 2021, HD Video, sound, 29:37 min

The following year, I found myself in front of the Flushing Library again. I was meeting a new friend. His gaze felt warm on me. “Do you like 肠粉 [Cantonese steam rice rolls]” he asked. “I’ve been craving it for eighteen years,” I replied. We went to Joe’s Steam Rice Roll, a tiny stall in a mall crammed with stalls, where for $7.25 he unlocked a piece of myself that had been frozen in time. We hung out in Flushing often, to eat and watch movies, sometimes take walks through the streets, malls, food courts. We spent hours roaming the snack aisles of grocery stores, playing a game of Proustian excavation. Different items called to us, portals into long-lost memories – Yakult, wasabi peas, cream-filled koala cookies in hexagonal boxes, sausages individually wrapped in red-pink plastic, anything taro-flavored …

In recent years, Flushing has gotten more mainstream. Manhattanites and tourists now take the 7 train to the last stop in search of hotpot, soup dumplings, and karaoke. Online, Flushing vlogs and listicles abound. New developments are sprouting up, featuring luxury spaces my mother would never think to enter. Local spots that began as humble stalls in rundown malls – Joe’s Steam Rice Roll, Xi’an Famous Foods – found wider success, with shiny new locations in white neighborhoods. H Mart too has gotten trendy. Meanwhile, as restaurant chains from China move in to vie for Flushing’s newly affluent clientele, those old malls and hole-in-the-wall eateries of the early 2000s are quietly disappearing.

Where will the jianghu take us next?

Still from Lu Zhang, A Girl Sings Along Without Knowing the Words, 2021, HD Video, sound, 29:37 min

4. Xianü of New York

In the middle section of Ash Is Purest White, Zhao Tao’s character wanders alone through the ruins of China’s Three Gorges region, coming in touch with ordinary people drowning in the detritus of economic progress. We see that the jianghu derives its potency not from hypermasculine violence but from abiding reciprocity between those who have nothing, from the passions and desires that endure amidst the transactional relations of capital.

Charting the channels of this jianghu, Zhao Tao embodies the figure of the xianü, which translates imperfectly to “female knight-errant,” a variation on her role in Jia’s earlier film A Touch of Sin (2013), which, in turn, derives its title from one of the original screen xianü of Chinese cinema: the heroine of King Hu’s wuxia epic A Touch of Zen (1971).

After Hu, the xianü was taken up by the Hong Kong New Wave, in the gender-bending roles of Brigitte Lin in Swordsman II (1992) and Ashes of Time (1994), for example, or Maggie Cheung’s seductive snake spirit of in Green Snake (1993).

Still from Tsui Hark, Green Snake, 1993, 99 min.

The jianghu flows intertextually, spilling over temporal, spatial, medium borders. Toward the beginning of Green Snake, the older white snake Bai (Joey Wong) is drawn to the sound of students reciting Tang poetry, specifically Li Bai’s 静夜思 (Quiet Night Thought):

床前明月光,疑是地上霜。

举头望明月, 低头思故乡。

Lines that have been recited ad nauseam by generations of Chinese students. In Green Snake, the poem leads Bai to the scholar Xu Xian, who embodies the kind of Confucian ethics and respectability she hopes to attain. Twenty-five years later, in Ling Ma’s Severance, this same poem appears, the clichéd phrases taking on strange new meaning.

The novel’s Chinese American protagonist Candace Chen takes a work trip to Shenzhen, where she learns, for the first time, that her Chinese name is a reference to the Li Bai poem. Candace finds the English version and reads it to herself:

“Seeing moonlight here at my bed

And thinking it’s frost on the ground,

I look up, gaze at the mountain moon,

Then back, dreaming of my old home.”

Still from Tsai Ming-liang, Goodbye, Dragon Inn, 2003, 81 min

For much of Severance, Candace wanders New York City alone. She embodies a new kind of xianü, the xianü of diaspora.

Roaming around lower Manhattan, Candace stops at Chinatown for a solitary lunch of dumplings and milk tea, peeks through apartment windows in the evenings, continuing the routine five days a week, eight hours a day: “The thing was to just keep walking, just keep going, and by some point, the third or fourth hour, the fifth or sixth, my mind drained until empty. Hours blurred together.” Candace takes photos as she walks, then later uploads them to her blog NY Ghost: “The ghost was me.”

Later on, at a house party she hosts, Candace drifts from room to room, at a cool remove from the scene: “I was like a homeless person in my own house. I was enjoying myself, but it was an insulated enjoyment. I was alone inside of it.”

Toward the end of the novel, as the world falls apart, Candace takes up her old walk-and-photography routine again, pointing her camera at deserted streets, shuttered landmarks, waterlogged subway stations after a deadly virus wipes out most of New York. But the mood is somehow the same as before: she walks, photographs, observes … homemaking among ruins is nothing new.

During the pandemic, I obsessively read and reread Severance, reveling in its precise, hallucinatory descriptions of Fuzhou, Hong Kong, New York. The virus in the book, called Shen Fever, is triggered by nostalgia. Its primary symptom is the blind repetition of old routines; its victims become lost in memories, their actions stuck in an infinite loop. “Candace doesn’t get fevered because she has no sense of attachment to anything, nothing to be nostalgic for,” a friend theorizes to me one night, as our conversation circles back to Ma’s novel.

Still from Jia Zhangke, Ash Is Purest White, 2018, 136 min.

“English is just a play language to me,” observes another of Ma’s characters in her short story collection Bliss Montage Stories (2022), “the words tethered to their meanings by the loosest, most tenuous connections. So it’s easy to lie. I tell the truth in Chinese, I make up stories in English.”

An echo of what I once told a friend: “English is my primary language but it leaves me feeling cold; Chinese warms me; in English I am untethered, unfeeling.”

A striking statement, but it’s not quite true, as I feel myself drawn into the flow of English again, words and phrases eddying around my brain and cascading out of my mouth like magic.

I know that I will always live in this push and pull; the feeling of not quite; the euphoria and despair of unmooring; the ever-winding, ever-circling drift along these rivers and lakes.

**

My suspended face

tilt toward dusk

toward you –

On the beach at night again,

shipwrecked from language,

I touch a finger to the

watery swirl at the world’s edge.

And the next morning always

sun-dappled,

here by the kitchen window.

Hair flutter in the

Cantopop wind.

Long cadence,

infinite hunger –

___

This essay is adapted from “On Jiangju and Diasporic Worldmaking” in Lu Zhang ≈ HuaiErDeMan (Wildman) Clab, forthcoming from Gong Press in May 2024.