Launched in 2017 in celebration of the house’s 70th anniversary, the exhibition “Christian Dior: Designer of Dreams” has since embarked on a non-stop, globe-terraforming circuit of some of the world’s largest art institutions. Its journey only recently concluded at Tokyo’s Museum of Contemporary Art, “Designer of Dreams” also toured Paris, London, Shanghai, Chengdu, Doha, and New York. And the dream doesn’t stop there: Other Dior retrospectives have simultaneously appeared: “The House of Dior: Seventy Years of Haute Couture” at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne (2017); “Christian Dior: History and Modernity, 1947-1957” at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (2017) and the McCord Stewart Museum, Montréal (2020); and “Dior: From Paris to the World” at the Denver Art Museum (2018) and the Dallas Museum of Art (2019). Alongside annual shows at Musée Christian Dior in Normandy, should we also prepare for the blitz of his 80th anniversary in four years?

Dior, of course, is no stranger to hagiography: Even the most puritanical scholarship extols how he single-handedly revolutionized the woman’s New Look and rescued France from postwar economic misery. But why fashion’s growing obsession with museum blockbusters? And do such partnerships diminish our museal tomes of culture? While it’s clear that museums make enterprising benefactors for design houses’ largesse, we should look beyond longueurs on the collusion between museums and markets (as if art’s status wasn’t always shaped by the magic of its own lucre) and appreciate the history of their popularity, alongside the innovations of their outsider counterparts.

View of “Christian Dior – Designer of Dreams,” Tokyo Museum of Contemporary Art, 2022. © Daici Ano

View of “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination,” The Cloisters, The Met, New York, 2018. Courtesy: The Met

The fashion blockbuster’s swollen vogueishness is often credited to “Savage Beauty,” the Alexander McQueen retrospective curated by Harold Koda and Andrew Bolton at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute. Opening in 2011, with preparations begun only weeks after the designer’s suicide, the show was visited 661,509 times, making it the Met’s 8th-most attended exhibition and necromancing McQueen’s immortality. Premium tickets were sold for Mondays, when the museum is normally closed, and for the first time in the Met’s 141-year history, daily opening hours were extended until midnight. As membership soared, the Met’s campaign for fashion mega-blockbusters intensified: Four years later, “China: Through the Looking Glass” drew 815,992 visitors; in 2018, “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination” scored a priestly body count of 1.65 million, becoming the most-visited show in the museum’s history. Fashion’s grand narratives clearly captivate the public.

While some aesthetes may abhor the metrics of attendance, it’s hardly a recent phenomenon, nor is it unrelated to the exhibition’s seemingly religious import. The rise of the fashion blockbuster occurred over a century earlier at the world fairs. While not formally “museums,” special fashion pavilions, like those at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, exhibited contemporary couturiers in large, opulent scenes and used creative methods to display historic dress, promoting the nation’s technical craftmanship and visionist elegance. For the 1925 International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, French couturier Jeanne Lanvin curated two major sites devoted to fashion, the Grand Palais and (literally) the Pavillon de l’Élégance, that mounted work by the likes of the House of Worth, Callot Soeurs, and Madame Jenny on stylized mannequins among art-deco furnishings. These pavilions often attracted upwards of one million visitors and revealed the public’s keen interest in fashion display as a powerful form of patriotic nation-building.

Perhaps the luxury logo, as readymade oracle, is the best mirror for our collective drive.

Most familiar of blockbusters are the heroizing designer retrospectives that kicked off in the latter part of the 20th century, such as the Met’s 1983 retrospective of Yves Saint Laurent, its first of a living designer. The landmark occasion, however, is equally historicized in scholarly circles by the condemnation it received. Art critic Robert Storr wrote in Art in America, “Fusing the Yin and Yang of vanity and cupidity, the Yves Saint Laurent show was the equivalent of turning gallery space over to General Motors for a display of Cadillacs.” Arguably more criticized still was the Guggenheim’s 2000 retrospective of Giorgio Armani, organized by Germano Celant and Harold Koda, both for the overly commercial designs on display and reports that Armani had just donated fifteen million dollars to the institution. Did YSL’s high-street glamor and Armani’s conservative sensuality warrant the prestige expected from hoary hierarchies of cultural production? Or did they appeal to something higher: the desiring machine of industry? In his unfavorable review of “Armani,” which went on to tour Bilbao, Berlin, London, Rome, Shanghai, Tokyo, and Milan, fashion historian Christopher Breward also conceded, “The catwalk and the department store vitrine have, in some respects, supplanted the artist's atelier as a fulcrum for the expression of modernity.” Perhaps the luxury logo, as readymade oracle, is the best mirror for our collective drive.

Of course, not all fashion exhibits simulate the status quo at such a dazzling remove. Even the mothership of fashion blockbusters, the Met, has inspired new collaborative poesis. For “Renaissance in Fashion, 1942,” opening in its titular year, twelve New York designers were invited to create specially made ensembles inspired by the art and costumes in the museum’s Renaissance collection, which were staged among the majestic pillars of the entrance hall on mannequins designed by the department store Bonwit Teller. Conceived during the German occupation of France, which isolated the US from the cradle of couture, the exhibition foregrounded the inventive work of local designers usually overshadowed by their Parisian counterparts. Besides expressing patriotic rebirth, the exhibition, chaired by Ethel Frankau, director of Bergdorf Goodman’s custom salon, demonstrated a lively collaboration between a museum and new fashion talent. Jessie Franklin Turner’s dinner dress of pheasant-colored velvet, paneled with antique Russian brocade and fastened with antique Persian buttons, remains an achievement, and was beautifully redisplayed in the Met’s 2022 exhibition “In America: An Anthology of Fashion.”

A more contemporary lodestar for experimental fashion museology, Antwerp’s Mode Museum (MoMu), likewise spotlights local designers and often co-curates solo shows with their subjects, mimicking the designer’s radical design methodologies within an exhibition itself. Bernhard Willhelm’s 2007 retrospective “Het Totaal Rappel” (The Total Recall) marshaled an ad hoc, utterly unhinged scenography replete with TV sculptures, cardboard caves, and four-legged mannequins, brilliantly mirroring the eccentric, folkloric, and homoerotic sensibilities of Willhelm’s collections. That same year, meanwhile, “Yohji Yamamoto – Dream Shop” recreated pieces from Yamamoto’s prior collections for audiences to try on, subverting the ocular ideal of the ennobled object. Two years prior, for “Katharina Prospekt: ‘The Russians’ by A.F. Vandevorst,” the Antwerp label A.F. Vandevorst organized an exhibition on Russian dress using material from the State Historical Museum of Moscow and MoMu’s own collection, taking a provocatively impressionistic approach to curating national dress. Of course, the list of such experimental fashion exhibition-making is too immense to catalog here; fashion curator Julia Petrov dates their history as far back as the early 1900s.

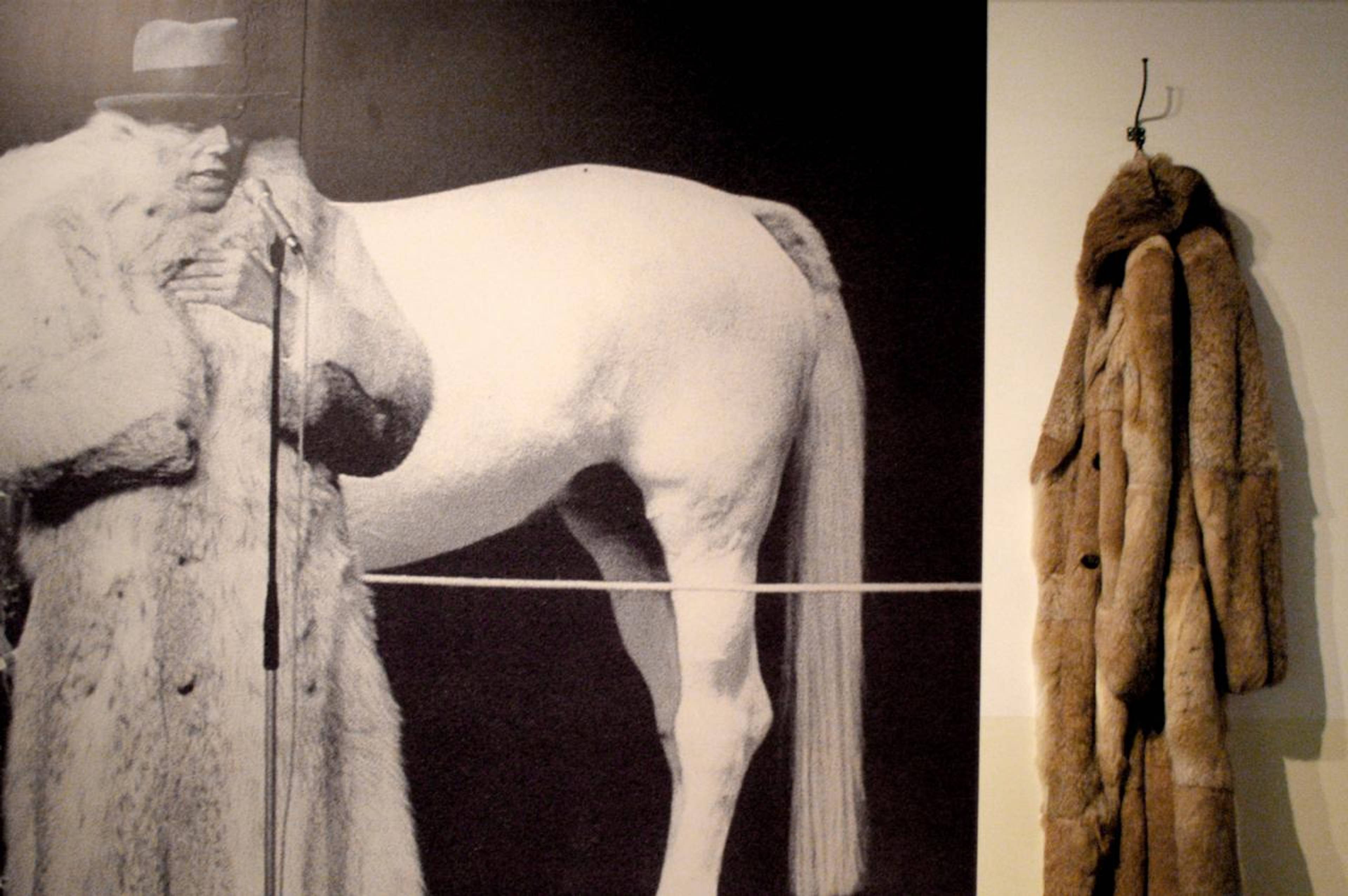

View of Bernard Willhelm, “Het Totaal Rappel,” MoMu Antwerp, 2007. © MoMu Antwerp. Photo: Ronald Stoops

View of Katharina Prospekt, “The Russians by A.F. Vandevorst” MoMu Antwerp, 2005. © MoMu Antwerp. Photo: Ann Vallé

One final, instructive example, however, is PS1’s little-remembered fashion program, operating almost as a testing ground for future models like MoMu’s. In 1978, at the invitation of PS1 director Alanna Heiss, Hollywood Di Russo, a hair and makeup stylist and downtown bon vivant with no prior curatorial experience, launched a visionary program consisting of mostly solo shows by young local designers. In “Art as Damaged Goods” (1982), African American streetwear designer Willi Smith covered his collection in plaster-like material and laid it across the floor accompanied by evidence number cards, evocatively turning the exhibition into a crime scene. In her eponymous 1983 show, Betsey Johnson had the walls schizophrenically hand-taped with her sketches, reference images, press clippings, and ramblings drawn in black marker, while mannequins wearing her clothes danced across the entrance of the gallery; the slapdash, diaristic design embodying Johnson’s proto riot grrrl attitude. For his own exhibition, the designer Julio Espada only revealed his work, a series of tissue paper dresses, to Di Russo the day of the install, yielding a highly contingent display. Such exhibitionary tactics reveal the improvised, destructive, and embodied qualities of fashion that are otherwise faded in Dior “Designer of Dreams.”

The fact is, unlike art, fashion does not enjoy an exhibitionary ecosystem of commercial galleries, artist-run initiatives, non-profit institutes, European kunsthalles or Chelsea blue-chips. Fashion exhibitions are primarily relegated to the museum space, and with it, the spectacular and prudential strictures of institutional patronage. Purchasing large swaths of this real estate are the touring juggernauts funded by the fashion industry’s louche in-kind budgeting. This isn’t necessarily “bad,” as they can vivify grand narratives around nationalism and luxury’s capitalist realism. But greater exposure to their experimental counterparts might also encourage new renaissances in fashion, integrating exhibitions as powerful agents for fashion’s changing cycles.

View of “Fashion (Winter 1983): Betsey Johnson,” New York, 1983. Courtesy: the artist and MoMA, New York

Salon de la Maison Lanvindans, “International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts,” 1925, Pavillon de l'élégance, Paris. Courtsy: Musée des Arts décoratifs, Paris

___