Every so often in life, I ask myself where a great place would be to stand and dabble in the simplicity of feeling sad. Saks Fifth Avenue? Selfridges? KaDeWe? On which floor? Should it be less glamorous, like an outlet, or further down the supply chain, like a factory? Maybe outside a government building? Something divisive, like a ministry of defense? Or something more neutral, like an embassy?

In his entire artistic career, Peter Halley only made one video work and the year was 1983 and he titled it Exploding Cell. A chunky screen plays it on repeat, directly situated on Mudam’s honey-colored French limestone flooring à la Magny Doré, set apart from the large, Neo-Geo, Neoconceptual, post-modern architectonic canvases that constitute the majority of “Conduits,” his 2023 retrospective in Luxembourg – every Hallmark movie’s definition of any European place − and I guess the point I’m trying to make is that watching a supremacist square explode on repeat doesn’t prompt additional sadness, so much as it supplies a calm backgroup to contemporary Western melancholy.

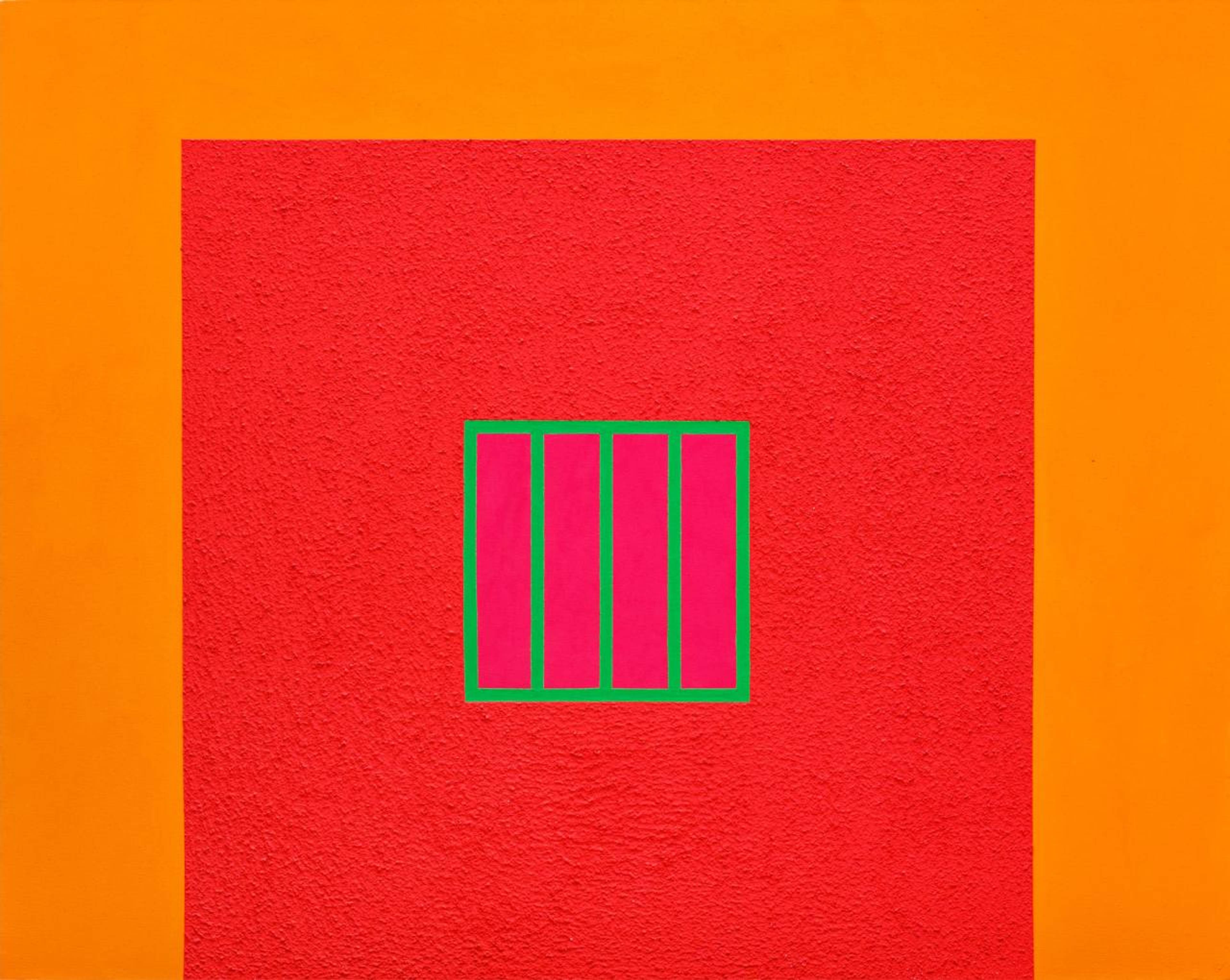

Peter Halley, Day-Glo Prison, 1982, fluorescent acrylic and Roll-a-Tex on canvas, 160 x 196 cm. Courtesy: the artist

View of Peter Halley, “Conduits: Paintings from the 1980s,” Mudam Luxembourg, 2023. Courtesy: Mudam Luxembourg. Photo: Mareike Tocha

In a recent interview with critic Max Lakin, Halley said that Europeans are not afraid of coolness, and that he gets a kick out of seeing photographs of his paintings in monochromatic homes. I, too, wish I could observe the sun rise through the steel-gridded, open-plan Bauhaus windows of a secluded estate somewhere in Central Europe, watching not the sun, but its angular rays as they cast conduit-like patterns, first climbing the metallic legs of a Barcelona Chair, then slowly advancing onto the mahogany-leather upholstery of its Daybed equivalent and the smooth, primavera wood wall finishing, cathartically reflecting the florescent paneling of Day-Glo Prison (1982) over a minimalist fireplace. This experience alone would be supreme in its material perfection, in the sharpness of its every edge, in the Greenbergian recreated flatness of its composition. Blending in with the projected ideals of the objects decorating my cell, I would achieve artfulness and sophistication, obsessively playing a vinyl of Roxy Music’s “In Every Dream Home a Heartache” (1973). In the same text, Lakin called Halley’s works “parodies of Modernism,” but I think he’s pretty serious about them, upholding their timeless relevance through a distinct “penthouse perfection” aplomb.

The trams in Luxembourg are compartmentalized in seven sections and each section benefits from the atmospheric glow of differently colored sliding doors, assimilating the palette of Halley’s late 80s works: joyful, in a weird, deceiving way. Luminal glows of purple, light-blue, green, and cyan meet seating upholsteries of plastic gray. Departing the EU corporate realism of the city’s north, i.e., the European Investment Bank and the adjacent campus, one crosses the Uelzecht river on the way, as backward in time, toward a more feudal side of town. This journey will unironically be accompanied by Angelo Badalamenti’s Twin Peaks (1990–91) score, which tunes in and fades out between each station. That already makes it cheap, too obvious, then, to point fingers at Luxembourg and call it an archaic stage prop of kitschy Euro-play. Few spots remain to us, those that feel especially estranged; instilled in time-lock, their reason for being never really fundamentally changed.

Back in Berlin, entering even the newest buildings has come to feel like dwelling in the ruins of an invented heyday.

Coined by Louis-Sébastien Mercier and later reverberated by Walter Benjamin to dissect the psychology of 19th-century Parisian urbanist architecture, “phantasmagoria” is characterized by a ghostly past making a superficial comeback, not as part of the present one knows to be “true,” but visually and physically tangible as though it were. A hollow projection of someone’s ancestor or the pop-up shops at the Galeries Lafayette are in principle the same: Environments assimilate to ghosts when their aesthetic appearance masks an underlying objective purpose of being there.

Back in Berlin, entering even the newest buildings has come to feel like dwelling in the ruins of an invented heyday. As the cracks of societal cohesion become ever steeper and impossible to ignore, culture remains in limbo. Many of us use big words to talk about the future, masquerading having given up on the present, continuing as though nothing was ever at stake.

Left: Charles Marville, Passage de l’Opéra (Galerie de l’Horloge) (ninth arrondissement), 1868, albumen silver print from glass negative, 35.5 x 26.5 cm; right: Charles Marville, Passage de l’Opéra (de la rue Lepeletier) (ninth arrondissement), c. 1868, albumen silver print from glass negative, 36.5 x 22 cm. Courtesy: Musée Carnavalet, Paris

I relegate the prospect of ending it all to yet another phased-out day, instead making my way to the Ringtheater for Ghosts of the Landwehr Canal (2023). Written by Travis Jeppesen and directed by Wang Ping-Hsiang, the play stars the spirit of Rosa Luxembourg, an anonymous specter who claims to be the Romanov Grand Duchess Anastasia, and a still-living Maoist worker ant who drifted away from her colony into a continuum beyond time and space. The setup instantly reminds me of Sartre’s infamous play No Exit (1944), except that instead of resignation to a categorical afterlife, Jeppesen’s characters’ main source of frustration springs from their enforced oscillation between a hyper-manic camp of the living and a similarly chaotic realm of the dead.

As they fail to urinate and deflect their labor value into cam-sex chatbots, the trio reflects upon capitalism’s tendency to self-annihilate, failed Marxist revolutions, and their interrelated personal origins, weaving satire together with figurative and literal histories. They blame one another, then themselves, then identity and class, emancipating from the former, breaking allegiances on grounds of the latter, gesticulating with found dildos in increasingly inventive anarchic grabs. Alive enough to be burdened by guilt, dead enough to be incapable of backpaddling change, conflicted between revolution and self-indulgence, each narrative floats around like a DVD-screensaver logo, jumping directions and colors every time it bumps into the hard edge of yet another frame.

Tien Yi-Wei in Ghosts of the Landwehr Canal, directed by Wang Ping-Hsiang, Berliner Ringtheater, Berlin, 2023, performance documentation. Photo: Ulf Germann

Front to back: Moritz Sauer, Tien Yi-Wei, and Wu Po-Fu Ghosts of the Landwehr Canal, directed by Wang Ping-Hsiang, Berliner Ringtheater, Berlin, 2023, performance documentation. Photo: Toni Petraschk

The play was ingeniously staged; its use of media screens was visually innovative; its characters were the right amount of vulgar, while remaining articulate; and the audience laughed repeatedly. Jeppesen’s construct managed to tick a vast range of in-the-moment topics without feeling like too much discourse chase. Its punch at the cliché Berlin party paradox – that of the scene’s unethical drug sourcing contradicting its own supposed social ideals – felt like a tired criticism, but I'll let it pass without objection, because any reminder that the bottom line is an ongoing class war forever legitimizes the happening of any cultural soirée.

Outside the venue, an American stranger breaks the ice by asking if Berlin is really the capital of failed suicides and if ghosts run the streets of Kreuzberg at night. I answer with a meager “yes,” but my argument only gains sustenance as I numb myself with quality screentime surfing the U8. Someone posted: “My son just told me that ‘tradition’ is just peer pressure from dead people.” Someone else replied: “Not us being bullied by ghosts.”

the hustle and bustle of any metropolis produces forms of jadedness that, in their most extreme, can be confused for immortality.

As a Berliner, I don’t consider myself bullied into our traditionally low working morale, our collective tendency to procrastinate, or our habitually unquestioned debauchery. Under the watchful gaze of our infamous TV Tower, ghosts and suicides assume a different shade. Comparing oneself to the seasonal spring, there are so many ways to think about the unlikelihood today of feeling reborn and whether our anthropogenic inability to reverse change means hanging around like animations of flute-playing skeletons straight out of an Özgür Kar videographic display. I think people move to Berlin to live on their own terms, and I deduce they’d prefer to die that way, too. Then again, the hustle and bustle of any metropolis produces forms of jadedness that, in their most extreme, can be confused for immortality, and many here tend to forget the finitude of their own stays. We are haunted, we haunt ourselves; death is close and infinitely far away.

“What the hell is ‘The Palliative Turn’?” the American stranger asks, picking up a magazine from the stash of books crowding my desk. As I struggle to put my pants back on, I gasp, thinking this whole suicidal, humanities-undergrad look is becoming increasingly passé. Wanting to break patterns, I venture that it’s a manifesto by an interdisciplinary group of artists, comedians, kinesiologists, critics, philosophers, palliative care experts, and curators turned morticians, all of whom share an interest in nihilism’s potential to frame nicer, more realistic, and more genuine ways of art creation under the credo of indulging in the relief that it will all just drift away. “The apocalypse calls for Palliative Pilates,” I conclude, giving my guest a sign to please not, under any circumstance, make himself at home. Instead, oversaturated on contemporary discourse, I flicker through The Waste Land (1922):

Your arms full, and your hair wet, I could not

Speak, and my eyes failed, I was neither

Living nor dead, and I knew nothing,

Looking into the heart of light, the silence.

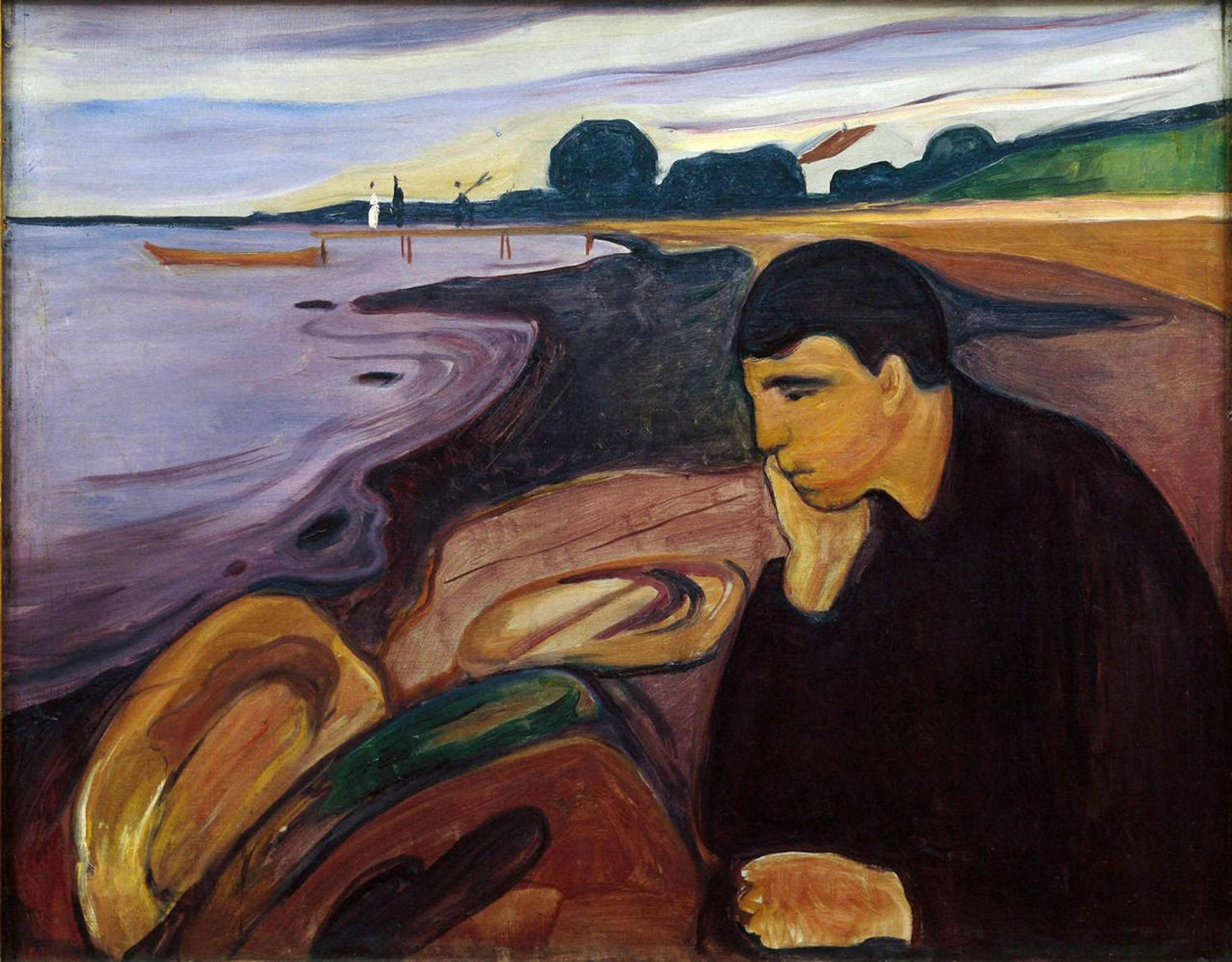

Edvard Munch, Melancholy, 1894–96, oil on canvas, 81 x 100.5 cm. Courtesy: Bergen Kunstmuseum

___