In the summer of 1949, ten members of the CoBrA group (an international group of artists and literary figures from Denmark, Belgium, and the Netherlands active between 1948 and 1951) moved, with wives and children in tow, into a house in Bregneröd, a village nestled in the wooded countryside near Copenhagen. In contrast with the utilitarian architecture that was beginning to impose itself in the West, the construction of a communal, playful, and changing model of living was made possible by rejecting academicism, the logic of the market, and the frontier that traditionally separates art and life.

In the book Critique de la vie quotidienne (Critique of Everyday Life, 1946), sociologist Henri Lefebvre describes the human condition as vitiated by habits and routine, the ruling class’s powerful brake on man’s creative potential. The latter seeks in art a way out of this repressive condition, exemplified in the grayness of cities and the automatism of factory work. In response to the Corbusian housing model widely employed by the cement and entertainment society – Brutalism’s rectilinear, functionally optimized, cookie-cutter solution to post-War urbanization – one of CoBrA’s cofounders, Asger Jorn, wrote to the painter Enrico Baj to propose an exciting and chaotic idea of architecture: “The house must not be a machine for living, but a machine for shocking, impressing, a machine of human and universal expression. This is the new architecture.”

Casa Museo Jorn, Albisola, 2023

David Adamo, Giacomo Porfiri, and Wolfgang Staehle, Just a suggestion, 2023, rope, pullies, steel, and hand-woven hammock

In 1957 in Cosio d’Arroscia, a small commune in the mountains of northwest Italy, Jorn co-founded the Situationist International, Europe’s last aesthetic and political avant-garde and the antechamber of 1968 movements. He then bought a ruined farmhouse an eighty-kilometer drive east, in the foothills of Albisola, the renovation of which would become an opportunity to concretize his theories on living and building. Until his death in 1973, Jorn intervened continuously on that fiefdom overlooking the sea, converting it into an artist’s house and a total work of art.

Fifty years later, the Danish artist’s home, open since 2014 to the public as a house museum and already the site of prestigious exhibitions by Salvatore Arancio, Anders Ruhwald, and Louis Fratino, among others, has become the protagonist of a true artistic residency. Faithful to Jorn’s will, it has once again become an all-encompassing experience, as it was during its habitation and transformation by Umberto Gambetta, a close Albisolese friend of Jorn’s. Last autumn, its history and international, interdisciplinary, and experimental vocation offered a place for the artists David Adamo (*1979), Giacomo Porfiri, and Wolfgang Staehle (*1950) to pursue free artistic and poetic research, hypothesizing a “situation fiercely opposed to the degradation of everyday life.”

Wolfgang Staehle sits in The Lodge, 2023, chicken coop, chicken wire, reed, string, wire, wood, slate, and straw

David Adamo, Giacomo Porfiri, and Wolfgang Staehle, found stone, 2023

David Adamo uses a jetpack

Over the course of several weeks of intense work, the three artists, already accustomed to collaborating and free from mercantile pressures and media overexposure, used Jorn’s villa as a laboratory to demonstrate alternative ways of living and creating. The results of their residency, curated by Paola Gargiulo and Cecilia Nastasi, under the scientific direction of Luca Bochicchio, and exhibited last summer as “A CASA” (AT HOME), asked visitors to navigate a dense network consisting of more than fifty works, distributed more or less visibly in every corner of the house and garden.

Adamo used a wide range of different materials to foil common perception. Taking their cues from the everyday, his plaster and bronze works, such as the peel of a bronze orange “forgotten” on a radiator in the bedroom, are perfect imitations of reality. In other sculptures, Adamo seems to share Jorn’s fascination with pure, unfinished matter: His intervention in stones of various extractions is barely perceptible in Green and Drum, not denying their nature, but gently flaunting it.

David Adamo, Untitled (green), 2023, found stone and fuzz ball

Wolfgang Staehle, “Freedom and Democracy,” 2023, embroidery on kitchen towels, each towel 50 x 66 cm

Staehle, meanwhile, attempted to interpret the residency through his camera lens. In the cellar, a stop-motion sequence of 7312 photographs projected his trip by car from Berlin to the residency in Albisola. In his studio, the canvas A6, which had been mounted on the car’s roof, showed another record of the journey, in the dirt and insects it had collected. In the colorful and convivial kitchen, the collage Servant of the People (2022) introduces the cartoon character Goofy to a table of G7 representatives. On another wall hangs a series of embroidered kitchen towels (Untitled, 2022) featuring peremptory statements like “Freedom & Democracy” alongside reference to corporations that have undertaken nefarious or otherwise suspect activities.

Porfiri, in turn, made Casa Jorn itself the sole protagonist of his works. In his paintings, elements of the habitat that might ordinarily go unnoticed acquired a new charge. In Shelter #2, tar paper and bitumen dialogue with the black wall that divides the two bedrooms of the house. Even in his sculptures, Porfiri keeps the same poetic sensibility intact, making works which refer to discrete forms in Jorn’s house.

Giacomo Porfiri, Patch #1, 2023, bitumen on tar paper, artist-made frame

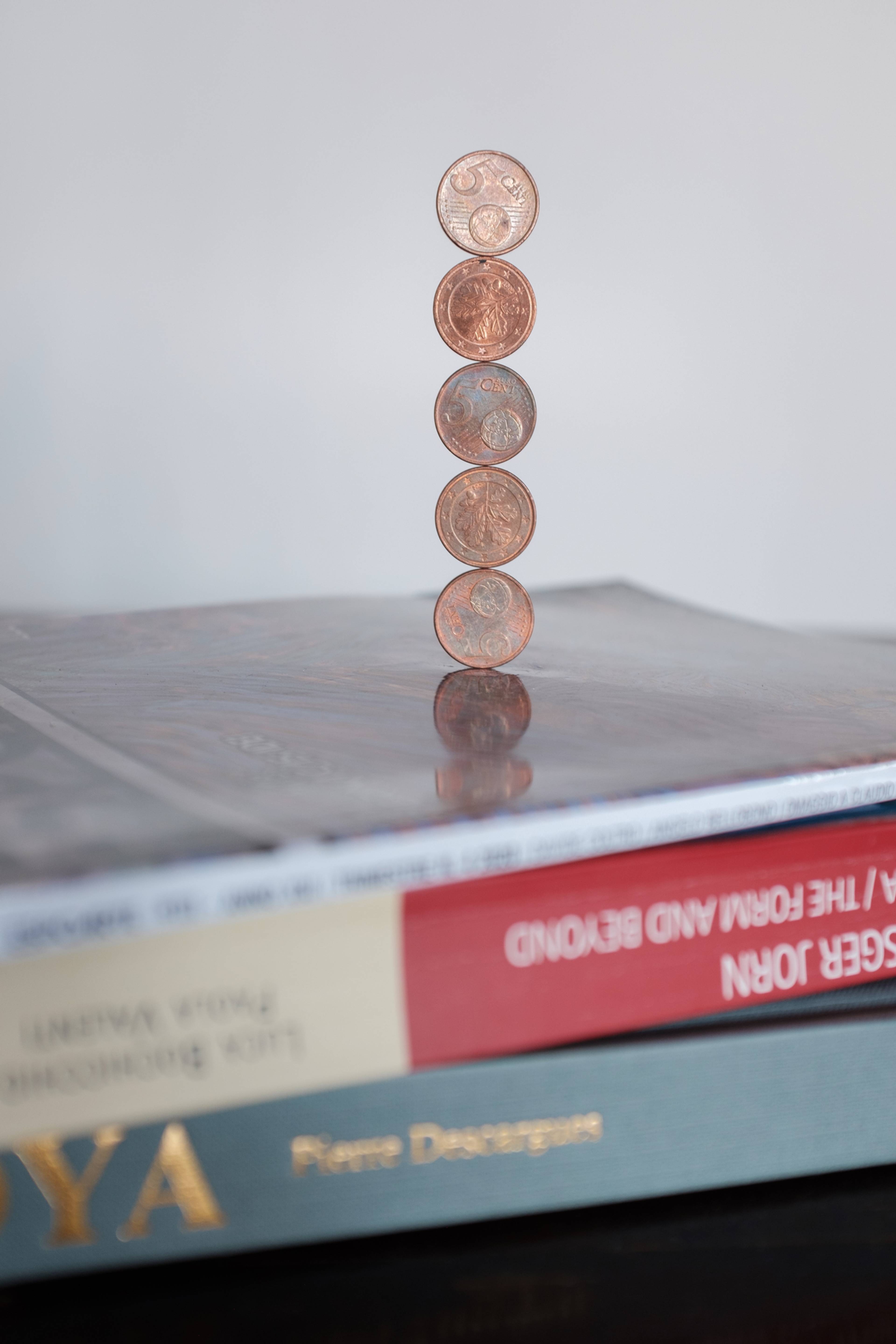

Giacomo Porfiri, Self-Portrait, 2023, five 5-cent coins

Working independently, jointly, and simultaneously, Adamo, Porfiri, and Staehle used garden and house as a matrix to generate new narratives and renewed reflections, sometimes troubling the authorial boundaries of the displayed works. I came to understand from visitors how unsettling it could be to see Australian chickens clucking around a museum, an expanse of porcelains simulating golf balls, or even to accept as a work of art a plastic straw twisted back on itself. Yet, by borrowing from the Jorn House Study Center photos taken by Gambetta and his family members in the 50s, 60s, and 70s, the mediation becomes simpler, clearer, more direct. Permeated by the magic of the place and Jorn’s poetics, the artists worked in a way that is deeply respectful of the place and its history, deliberately creating a dialogue that does not come across as disruptive or antithetical, but as a rigorous and well-considered expansion on the mysterious and programmatically incomplete visual manifesto on art, architecture, and life that is Casa Jorn.

“It is important to understand that poetry is not just something outside the essential needs of life, but that bread and wine are poetic, that a house is a poem and a city is an ornament, a precious jewel,” Jorn wrote. On the studio’s small balcony, a sign reading “VENDESI” (FOR SALE) created turmoil among locals for the duration of the exhibition. There were rumors that the municipality could no longer afford the management of the villa and was awaiting a proposal from the highest bidder. It turned out, though, to be just one of the artists’ many provocative attempts to turn the spotlight on a place from which they never wanted to part, and which will always welcome them as their own home.

David Adamo, Giacomo Porfiri, and Wolfgang Staehle, Vendesi / For Sale, 2023, sign

Portrait of the artists

___

“A CASA”

Casa Museo Jorn, Albissola Marina (Savona)