Internet art is metamorphosing. What began as folk “net art” in the 1990s became the conceptual “post-internet” in the 2010s, whose artists experimented with the digital image in the social media age. Post-internet reached its zenith in 2016 at the 9th Berlin Biennale, curated by DIS, only to descend – along with our hopes and dreams for a liberatory internet – into chaos, capitalism, and kitsch. It’s algorithms all the way down; economist Yanis Varoufakis calls this the era of “technofeudalism.” In return for subservience to our Silicon Valley overlords, we techno-serfs receive our pittance in “free” AI chatbots. Irrationality and addiction take hold as we surrender our private lives to public networks. Suddenly, everyone has either autism or ADHD. Unable to see through the fog, a new generation of artists look back in time to Romantic ideals.

Against the machines of the first Industrial Revolution, the Romantics abandoned reason to pursue the eternal and inalienable features of the human spirit: beauty, love, melancholy, and wonder. “All that stuns the soul, all that imprints a feeling of terror, leads to the sublime,” said Edmund Burke in 1757. Today, we exist in a sea of technological complexity in which Romanticism is reborn: individualism in influencers, melancholy in doomscrolling, love in devices, fear in AI. Vast, subterranean networks of fiber-optic cables crisscross the planet, offering an ersatz sublime at our fingertips. This is technoromanticism.

Teresa Fernandez-Pello, The Heart of Hurt, 2023. Installation view, Dordrechts Museum, Netherlands, 2023. Courtesy: the Dordrechts Museum

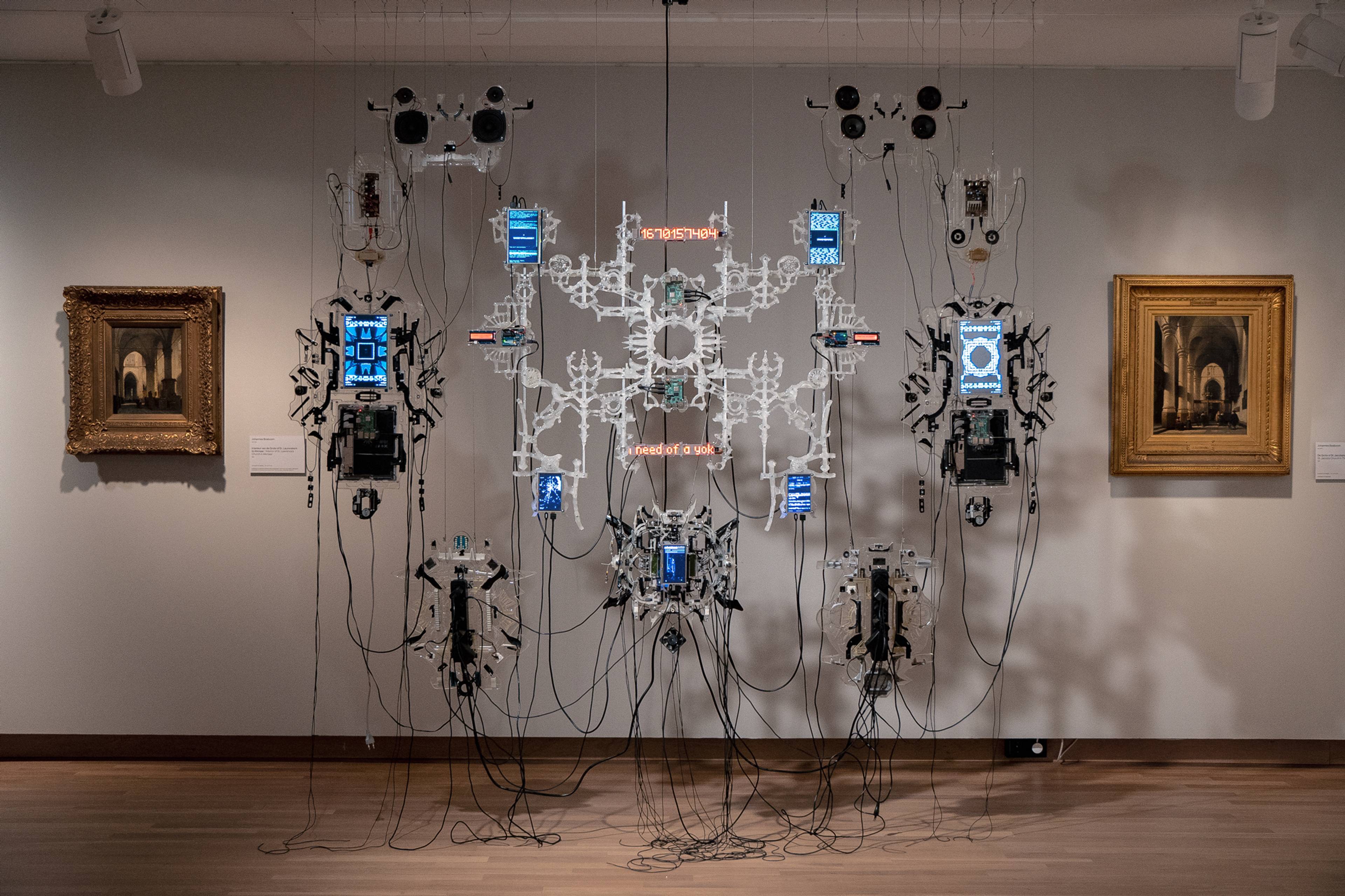

Technoromantics approach art-making opposite to post-internet, which was enamored by the possibilities of virtualizing the material world. Today, art speaks to a yearning for the opposite – devirtualization. Emerging artists materialize internet art in studio practice that sees traditional media interplay with electronics hardware, 3D printing, and virtual reality. True to this new materiality, works by Teresa Fernández-Pello and Brian Oakes are dark romances that forge Gothic architectural forms out of circuit boards and plastics. Fernández-Pello’s The Heart of the Hurt (2022) is a “neo-altarpiece” assemblage of 3D-printed acrylics and e-waste at which viewers can pray for deliverance to (or from) a techno-god. It recently showed in “A room with a view” (2023) at the Dordrechts Museum, Netherlands, where it was juxtaposed with two Romantic-era paintings of Gothic cathedrals by Johannes Bosboom. Its many LED screens flicker through database dumps, technical incantations, and Instagram URLs as modern stand-ins for stained glass, which, in their own time, transmitted the word of God. We have entered what artist and writer James Bridle calls the New Dark Age (2018), an era of uncertainty and superstition that plagues us with shadowy software and infinite feeds.

Brian Oakes’s techno-Gothic chandeliers are a recurring sight in downtown New York galleries, among them Dunkunsthalle and Blade Study, where the artist has a forthcoming solo show. Vessel 1 (2022) is a hanging, radial sculpture constructed from custom circuit boards, which, normally hidden, Oakes has exposed to the viewer. Demonic and shimmering, they come to life with watchful, blinking LEDs and moving arms. A mass of entangled wires spills from its core like dangling guts while embedded microphones warp back ambient sounds as electronic grunts and startling twitches. The creature is machine-learning embodied: It is Ophanim, the angel whose body is a wheel of flaming eyes. Begged to lean in, you feel uneasy standing close, as if it might strike you at any moment.

The technoromantic reimagines posting as liturgy, algorithms as messengers, and artists as saints.

Exposed circuitry departs from the post-internet gloss typified by DIS Magazine, which shined up or hid away the ugly parts of technology. Hardware is made visible, laying bare the flow of power and information, at the same time transfiguring electronics into sacred objects. The technoromantic reimagines posting as liturgy, algorithms as messengers, and artists as saints. They reach into a glorified past for motifs and meaning that invoke the aura of life before memes.Their aesthetic flirtation with the materiality of technology is a double-edged sword, however, that blurs the lines between critique and commodity fetishization. The stakes for this ambivalence are high at a time when capitalist technology is threatening human dignity and agency. Do we really want to engender an emotional attachment to the internet?

Genevieve Goffman’s Girl’s Balcony (2023), part of a commission by the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna for “/imagine: A Journey into The New Virtual” (2023), demonstrates how technoromantic artists use 3D-modeling to achieve intricate sculptural forms that defy post-internet’s neo-Duchampian attitudes. Digitally sculpted and laid down in thermoplastic nylon layer by layer, 3D-printing literalizes the process of devirtualization: the physical realization of digital forms. Goffman’s architectural miniatures address modernity as a moment frozen atop the remnants of a tempestuous history compressed into a tower of forlorn windows. Wistful furries gaze out from tiered balconies – an internet-infused anthropomorphism that evokes the haunted domesticity of Leonora Carrington’s surrealist paintings. Girl’s Balcony brims with nervous energy that anticipates an enormous future just over the horizon.

Genevieve Goffman, Girl’s Balcony, 2023, nylon. Courtesy: the artist

The Romantics – and, later, Surrealists – fetishized “the madman” as a conduit for genius. Reminiscent of the dancing plagues of the Middle Ages and Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” (1843), one such contemporary madman, Nicholas Sanchez, mobilized technoromanticism in his latest performance at the DIY show “Spiritual Warfare” in Los Angeles. Using his phone as a live prop, Sanchez calls into a live video that is projected behind him. He writhes on the ground as if possessed by demons and begs, “please post me, please post me,” carrying the act outside and back through the aisles of the audience. He addresses the audience through a heart-shaped ring light, who become the internet personified, a vulture’s eye which observes its weakening prey from afar. In his performance, Sanchez is reduced to a body which only exists to serve the gaze of the internet, and whose line of sight is broken by his own image. He is a man with no true identity – a trait of borderline personality disorder. The internet is giving us BPD; technoromanticism, the means to express it.

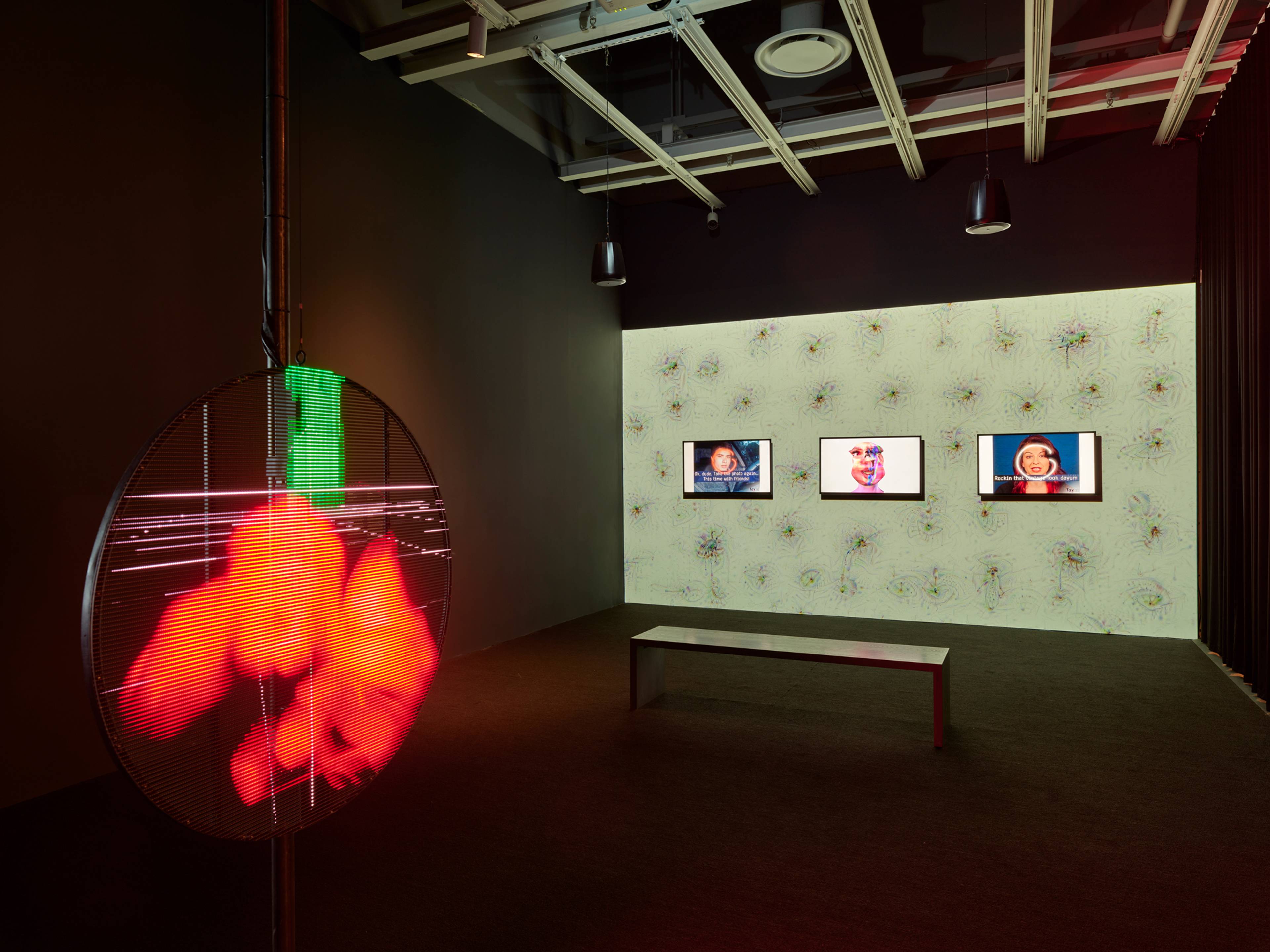

In the Whitney’s “Refigured” (2023), an exhibition of works in the museum collection dealing with virtual-material liminality, the astral, circular LED panels of Rachel Rossin’s THE MAW OF (2022) hung from the ceiling, conjuring ghostly images that wobbled and pulsed like an ultrasound of a digital avatar’s womb. Winged embryos and skeletal figures cut to infrared footage of her childhood neighborhood, suggesting a trauma response to a violent separation: the permanent exacerbation of the Cartesian split by physical and virtual technologies. Rossin’s answer is their reconvergence into what Jean Baudrillard described as “hyperreality”: a world that blends simulation and reality to the point we cannot differentiate between the two. She captured a picture of hyperreal space in her latest solo show at Magenta Plains, New York, where she juxtaposed THE MAW OF against painterly self-portraits inspired by her childhood drawings of the apocalypse. In doing so, Rossin connects the traditional arts with new media while lamenting the visions of doom that reflect in the looking glass.

Nicholas Sanchez, an almost promise / of love and devotion / our fear of falling together, 2023, performance documentation, “Spiritual Warfare,” Los Angeles. Photo: Nicholas Sanchez

Left: Rachel Rossin, THE MAW OF, 2022; right: Zach Blas and Jemima Wyman, im here to learn so :)))))), 2017. Installation views, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 2023. Photo: Ron Amstutz

Rachel Rossin, THE MAW OF, 2022. Photo: Kat Kitay

Richard Coyne wrote in Technoromanticism (2000) that “cyberculture invokes a romantic apocalyptic vision of a cybernetic rapture,” referencing the eschatological end-times event when the faithful will ascend from the material realm. While we wait, we build our own death cults. Advances in AI hearken the Singularity with Catholic e-girls as its acolytes. Tech bros and crypto investors proselytize accelerationist ideology while neo-reactionaries peddle Nick Land’s “Dark Enlightenment,” each signal escalating discontent with post-internet society. But the end-times these movements court, which frequently reference pessimistic, cyberpunk fiction, seem unlikely to deliver us from our woeful conditions. In times like these, technoromanticism asks an existential question: As the digital and virtual converge, and AI agents rise to power, what will remain of the human legacy?

Technoromanticism allegorizes the beauty and horror of postmodern life, entwined as it is with the fate of the internet. At its best, it makes a record of our endangered material reality and elevates our struggles above the infernal noise of digital mass media. At its most cliché, it parrots oversaturated online culture and entertains gloom-and-doom pastiche without saying anything at all. Post-internet had its flaws (namely, its overattachment to social media), but at least it was concerned with attacking emergent networks of control and influence, whereas technoromantic art risks becoming a product of the same. Emerging artists have the opportunity to reveal the secrets of our New Dark Age, but must beware its repetitive rhythms and too-easy pessimism. For this new period, I’ll offer an alternative allegory: Like the Demiurge of Platonic philosophy, an artisan deity that fashions the material world, technoromantic artists can reimagine human life in hyperreality as one where the surreal and sublime rise above networked society, rather than fall prey to it.

___