I’m landlocked, so one of the first places my mind drifts to is the sea. Growing up on the coast of Maine, I had no idea that neighboring Nova Scotia was such an epicenter for shipwrecks. In the evenings as a kid, I used to watch The Scotia Prince take its nightly voyage from Portland to Yarmouth. For reasons I’m not entirely sure of, the ship was taken out of commission and later relocated to the Indian Ocean, where it ferried folks between the mainland and Colombo, Sri Lanka. Like so many vessels of its size and use, I also learned that The Scotia Prince was sold for scrap metal and broken apart. When I saw Hira Nabi’s powerful docu-fiction All That Perishes at the Edge of Land (2019) at SAVVY Contemporary in Berlin last year, I wondered if one of those nameless, rusted-out hulls that was being stripped apart was The Scotia Prince. Probably not.

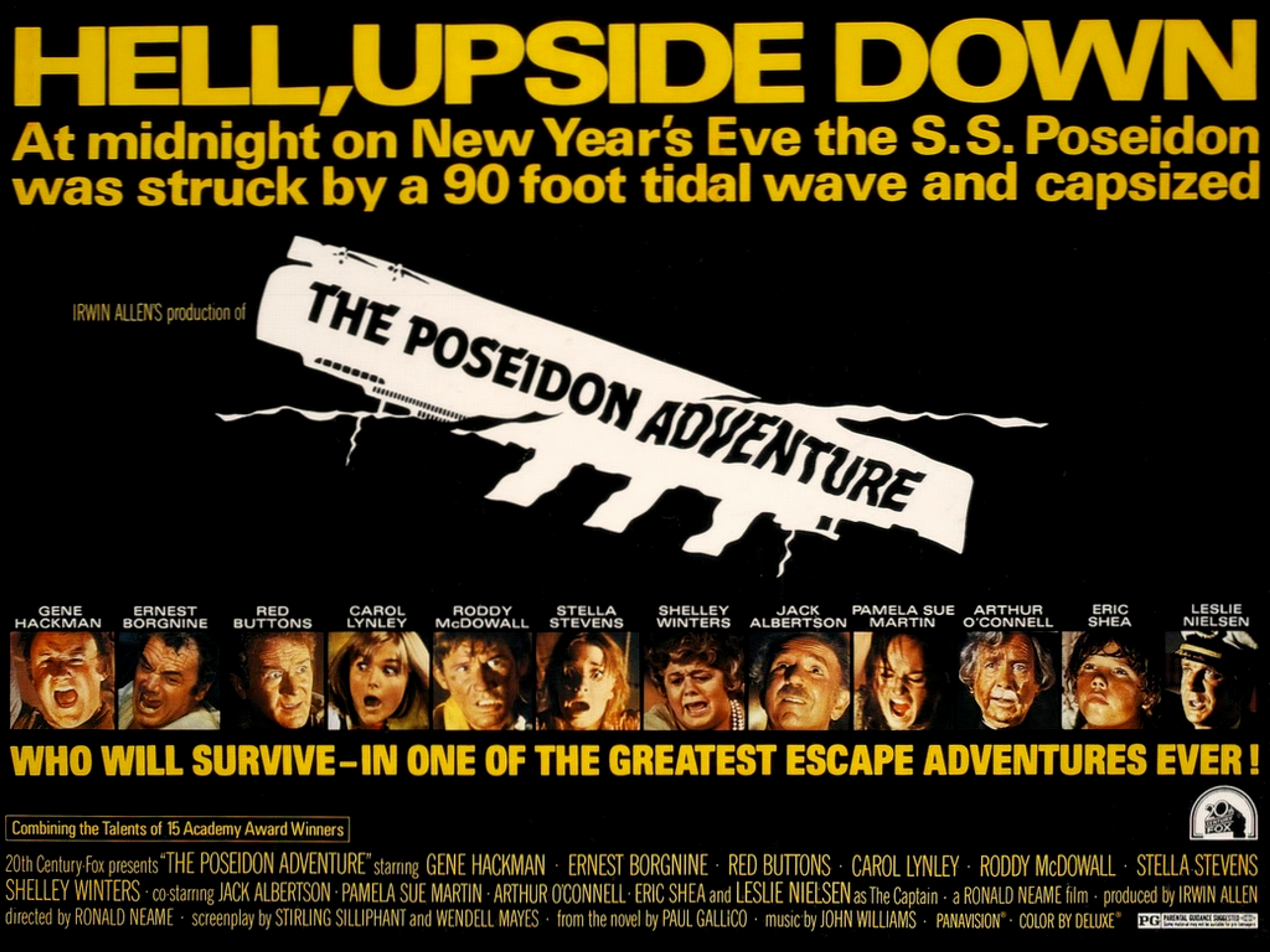

The problem with shipwrecks in general, at least as far as the images are concerned, is that they’re always viewed from the shore, at a safe distance. Otherwise, how would we know about them, or have images of these maritime disasters? Being in the shipwreck is hardly the same as watching a shipwreck, though I can’t say that I’ve ever seen one in person. I’ve just seen the shipwreck movies and pictures, like The Poseidon Adventure (1972), which was one of my favorites as a kid. The whole thing takes place inside, and the sets are an endearing mixture of fires and bursting pipes, water gushing in from every conceivable porthole and hatch. The most memorable scene is the beginning of the wreck, when the entire ballroom (it’s New Year’s Eve on the ocean liner) is turned completely on its head, and everyone has to grab onto something to keep from falling. In the film’s story, a tornado has managed to capsize the ocean liner, so the actual “wreck” is yet to come. The search for safety turns out to be a navigation of the vessels’ world turned upside down, the floor now a ceiling: the sea is above, not below, like the first words in the title of this Dirty Three song that I can’t stop listening to.

Maybe Hollywood, or some other place, will come up with a new Leviathan instead of a storm, something to take the pressure off of the pathos of survival, that would be cool. Did that already happen with Sharknado? Did I miss the boat on that one?

It’s a bit too pat to call the capsized ship a version of hell, but that’s exactly what one of the original movie posters claimed: “Hell, Upside Down.” It is definitely the inverse of some visions of heaven, like Pieter Bruegel’s Land of Cockaigne (1567), whose context must have been shadowed by the threat of shipwrecks, too. For some, like T.J. Clark, Bruegel’s painting of the afterlife is not an image upturned, rather: “it’s the world the same way up but only more so.” The wreck is a threat, a boundary to life, like the sea itself. I didn’t imagine The Scotia Prince ever sinking, though I wanted to when I took the trip to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia with my family and was so sick that I threw up for the entire journey. The daylight when we arrived was like the blinding sun of a terrible hangover: cruel and unrelenting.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Land of Cockaigne, 1567, oil on panel, 51.5 x 78.3 cm

I think I’m trying to weave a sailor’s yarn, but lately I’ve wondered if I’m the one who is actually weaving it, or if it is being woven for me by someone/something else. What is a sailor’s yarn? Something that is meant to hold things together, like stories, memories, narratives, both real and fictional? For philosopher Hans Blumenberg, the shipwreck is a metaphor for life itself, but no one today can have any illusion that whatever “life” is, it is not something given or guaranteed. Before moving through the litany of Western old dead dudes writing about shipwrecks, Blumenberg cautions his readers, “Even if private existence escapes shipwreck from inner perils, there still remain the great sinkings of the state, of the world, that can take it down along with them.”

The Poseidon Adventure, 1972, 20th Century Fox Theatrical Poster

The image of Shelley Winters character in The Poseidon Adventure reminded of the pre-meme cat poster that was around at the time I first started watching the reruns of 70s disaster films that played on Saturday afternoons. Hanging on is maybe a more relevant version of what to do in case of shipwreck these days; that is, if you’re on the ship. The perverse fascination of watching it all sink into oblivion was good old-fashioned distraction, entertainment, though I’ve heard disaster features are having a comeback as of late. The greater problem for me, is the difficulty in imagining what comes after – after the state, after the ship – the same problem Bruegel and others had in putting the afterlife into paint: How to imagine something other than this?

Stock photo of kitten hanging from a tree branch

Maybe Hollywood, or some other place, will come up with a new Leviathan instead of a storm, something to take the pressure off of the pathos of survival, that would be cool. Did that already happen with Sharknado? Did I miss the boat on that one? If not, I’d like to know how to visualize those who didn’t make it out alive, who were left behind, or not counted, or not on the register. What did they see when nobody showed up to rescue them? Visions of death and disaster are just too earthly, too much like everything else. What does the monster look like?

Théodore Géricault, The Wreck, 1821–24, oil on canvas, 19 cm x 25 cm