In cramped and peripheral cities like Beirut, distances are often foreshortened. Libelous wealth hides right behind the slum: One appears to go in an afternoon from attempting to assuage the woes of an impoverished relative to fist-fucking a Scandinavian consul’s husband in a penthouse apartment coruscating with Carrara marble. Maybe this is too specific. Or maybe it is every city on the right day, but not this or that footloose fairy’s life on any given afternoon. Nevertheless, this is how I’ve projected my impressions of Beirut, where I lived until the city’s recent economic collapse, onto the Beirut of artist, critic, and curator Nicolas Moufarrege (1947–1985), where he lived until the start of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975. I take this narrative liberty because his own self-mythologizing oversharing enjoins me to.

Moufarrege’s sparse retrospective at CCA Berlin, which is curated by Bidoun editor-in-chief Negar Azimi and CCA’s Edwin Nasr and shares a title, “The Mutant International,” with a series of essays the artist published in Art Magazine in 1983, culls an assortment of portrait drawings from the early 1970s alongside larger embroidered works from the artist’s time in New York, where he lived from 1981 until his death. In the first of several of Moufarrege’s eponymous essays, he divulges with the grandeur of history that he left Beirut on 22 November, the anniversary of both Lebanon’s Independence Day and the assassination of John F. Kennedy. The year he left, he made a needlepoint painting titled Le sang du phenix (The Blood of the Phoenix, 1975) upon arriving in Paris. If a certain brand of Lebanese nationalism had taken the phoenix’s rebirth as its crowning mea culpa after chronic tragedy, Moufarrege found the pompous pheasant’s bodily fluid splattered at the base of an Ionic column and committed it to canvas, gilding it in crimson alongside a botched cedar and a mutilated but still raised fist.

Nicolas Moufarrege, Le sang du phénix (The Blood of the Phoenix), 1975. Installation view, “Beirut and the Golden Sixties: Manifesto of Fragility,” Gropius Bau, Berlin, 2022

His writing from New York went on to extoll the activity coalescing in the since-fabled East Village scene, surveying the work of a group of peers that included Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, Chuck Nanney, and E’Wao Kagoshima, whom he curated together in multiple group exhibitions and who are largely affiliated with the half-remembered Figuration Libre (Free Figuration) movement. The texts are one part curator’s statement, one part artist manifesto, one part serial-comic-book-cum-superhero-picaresque, and five parts phantasmatic autobiographical glossolalia. “I am the Mutant International,” Moufarrege incantates throughout. Elsewhere: “I want my paragraphs and my pictures to be like film-strip slices of my mutant brain.”

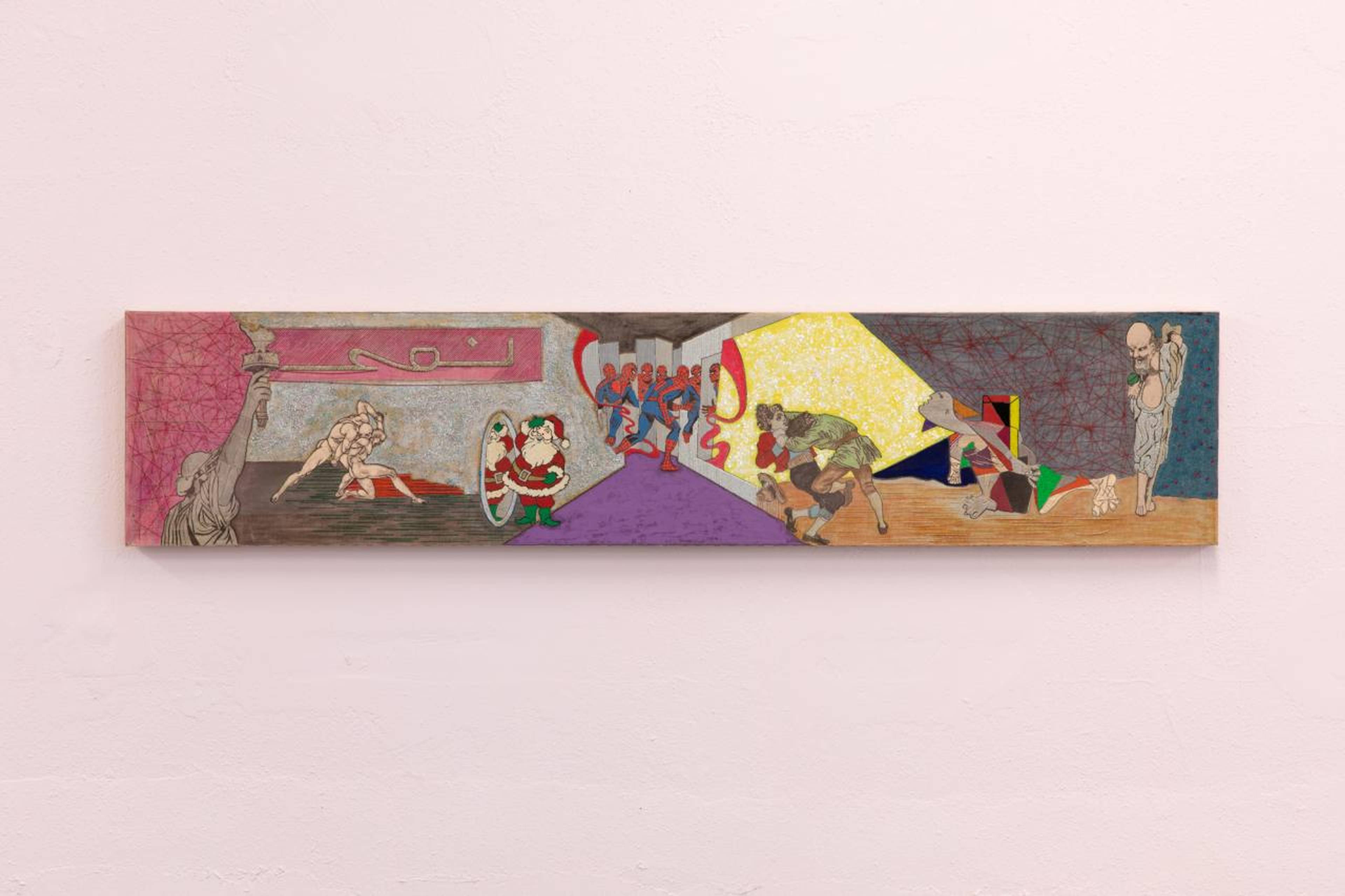

View of “The Mutant International,” CCA Berlin, 2023

By his own admission, Moufarrege confused “issues of art and criticism,” aiming to “chronicle [his] impressions'' in both, driving home the point that he thinks of his pursuits “not as expressive but as impressive.” This emphasis on “impressive” may be read in contradistinction to the “neo-expressionism” of the day, its astringently individualist pretensions and libertarian “self-expressiveness” excoriated by critics to this day. Moufarrege’s writing and art indeed betray a notion of self not as a coherent, congealed unit that must self-express; rather, the self is a harbor of discrete and syncretic fixations seemingly imbibed from all over and spat out verbatim, repetitively enough to imply an automatic subject who cannot resist the compulsion. The stitch is an itch of the Ich, but the Ich is everywhere. The intervals between the infinitesimal individual, the cosmopolitan, and the cosmic are collapsed. In the earlier works from Beirut and Paris, the artist’s impressions are redolent of a romantic-nomadic sensibility: ruminative, filled with trepidation as though at a precipice, yearning for the immemorial or for something greater, Sufistic, plangent. The works from New York on view at CCA, and especially those from right before his passing, such as Title unknown (Look Mickey, I’ve Hooked a Big One) (1984) – are brighter and wittier, more firmly metropolitan, self-conscious and almost scientific in their art-historical referencing, the appropriation turning outward within the same century toward Lichtensteinian neurotics and De Stijlian grids. Pick your Nick: old world: big fish, small pond; or new world: small fish, big pond.

The figures Moufarrege identifies with are numerous, anonymous, decisive, their inscriptions taking place privately or without a roof, all unremunerated by a market and impervious to conventions of taste.

But the artist’s craft lies not just in the mining of these impressions, be they of vertiginous inner life or of the annals of Pop. Moufarrege is not content merely beaming up scenes to Earth without any strings attached. As far as method and materiality, much is made of the artist’s embrace of embroidery and needlepoint in the 70s, when the lingering strictures of modern art still allowed sideways glances in the direction of techniques borrowed from gendered crafts either imposed on women or traditionally practiced by them as hobby. The artist Elaine Reichek, known for her exploration of histories of the embroidery sampler, was an interlocutor and close friend of Moufarrege. In a pair of untitled needlepoint canvases at CCA dated 1985, the lefthand composition consists of two stitch-by-number needlepoint kits issued by a company called Margot de Paris, both reproductions of Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Souvenir (1778), wherein a young woman engraves the initials of her lover in a tree trunk, which Muofarrege has set against a wallpaper of Egyptian hieroglyphs. One of the kits has NICK emblazoned across it in all-caps, the multi-color letters imitating a stencil print, both militaristic and childlike. The frame on the right is an embroidered reproduction of Lichtenstein’s Spray II (1963) depicting a spray-paint can stamped with the letter M.

View of “The Mutant International,” CCA Berlin, 2023

I’ll venture that the artist means to summon a very specific domestic scene by including the needlepoint ready-mades: I’ve seen many Fragonard reproductions, embroidered and otherwise, and even more stitch-by-number kits in middle-class homes in Beirut, and I’m certain Moufarrege did as well. Within the genealogy invoked by the work, needlepoint as social custom and form of enforced feminine preening trickles down across the centuries, from the French aristocracy before the Revolution, through the nascent bourgeoisie, and ultimately into home kits mass-produced and exported to wherever Francophilia has fractalized, Beirut included. The artist wonders: does the Levantine housewife purchasing the kit long for an Ancien Régime ? His answer, without passing judgment, finds an affirming (sur)realism even in the Rococo-lite commodity, one which stopgaps a desire not devoid of a utopian impulse. Juxtaposed as it is with Lichtenstein’s mid-action spray paint canister, the composition proposes some semblance of continuity between the depicted woman in love etching a letter into the tree; the domestic consumer of the stitch-by-number kit; the enjoyer of kitsch; the graffitist wielding the spray paint canister and tagging the walls of New York’s Lower East Side; and the artist himself. The figures that Moufarrege identifies with are numerous, anonymous, decisive, making do with what’s at hand, their inscriptions taking place either very privately or very much without a roof, all unremunerated by a market and impervious to conventions of taste. The Mutant International is everywhere.

View of “The Mutant International,” CCA Berlin, 2023

Critics of Moufarrege were not always so sanguine about his vision. In an essay published in 1984 in October titled “The Fine Art of Gentrification,” critics Rosalyn Deutsche and Cara Gendel Ryan decried Moufarrege as an “apologist” and “rhapsodic” “propagandist” of New York City Council-sanctioned gentrification of the largely immigrant and working-class Lower East Side. They cite his writings as an example of the effulgent and expansionist celebration of the artistic scene burgeoning around FUN Gallery, which staged Moufarrege’s second New York solo exhibition in 1985, and other newly opened commercial spaces in the neighborhood. Writing a year before his death, Deutsche and Gendel Ryan remark that the word “gentrification” never showed up in the artist’s essays. By turn, the word “AIDS” did not show up in theirs, though the years 1984 and 1985 were not yet the hours of mass mobilization against the disease. Gary Indiana, writing in 2004 about the East Village in the 80s after having witnessed first-hand how the disease ravaged that scene, is marginally more sympathetic to the kindled early-comers to the neighborhood, those who couldn’t be anywhere else by any means. He remarks as well: “New York’s best people [...] died fast in the AIDS epidemic or a few years into it,” specifically naming Cookie Muller, Peter Hujar, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Nicolas Moufarrege.

View of “The Mutant International,” CCA Berlin, 2023

In what way is Moufarrege a best? Indiana’s piece is titled “A Brief, Scuzzy Moment” – scuzzy, I could imagine, like a dance floor that is so greasy one might glimpse their own reflection in it. In that same vein, I think Moufarrege’s Mutant International excelled when it dug into discounted and dirty forms of consciousness, taking up as its own the everyday paraphernalia bridging a self to many others, when it reflected how the world-spirit manifests in kitsch, craft, cartoon, and graffiti, from across this and that border. “The international is spirit, sponge, and mirror.” Myself a chased-away émigré, I am likely prone to value this regard. But everyone else can pick their Nick.

View of “The Mutant International,” CCA Berlin, 2023

View of “The Mutant International,” CCA Berlin, 2023

View of “The Mutant International,” CCA Berlin, 2023

___

“The Mutant International”

CCA Berlin

10 Feb – 25 Mar 2023