Victoria Dejaco: Florentina, in your new piece Apollon Musagète, I recognized elements of things you have worked with before – bondage and various sports – but the it all came together blew my mind. Can you tell us about that, how it came together?

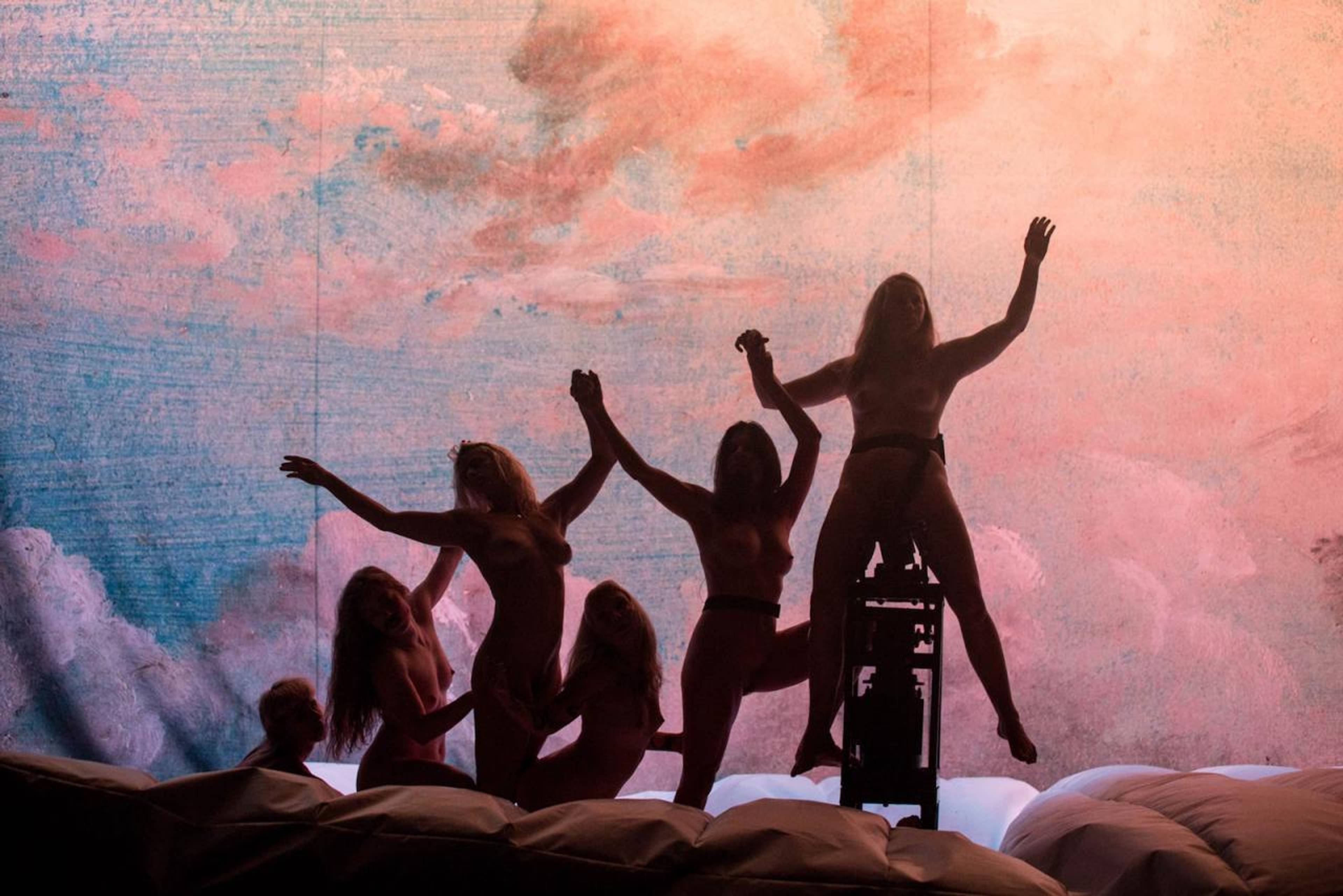

Florentina Holzinger: My starting point was the original Apollon Musagète , a neoclassical ballet choreographed by George Balanchine in the 1920s. It revolves around Apollo, the Greek God of music, who is visited by three muses – Terpsichore, the muse of dance and song; Polyhymnia, the muse of mime; and Calliope, the muse of poetry – and throughout the ballet he chooses his favorite muse. I saw this ballet and immediately wanted to redo it with an all female cast. I wanted different bodies attempting these forms and to see how the meaning of the choreography would change if there was no male Apollo. I kept looking at my cast thinking who would get to be Apollo, but we realized we all had to step in for him at certain points.

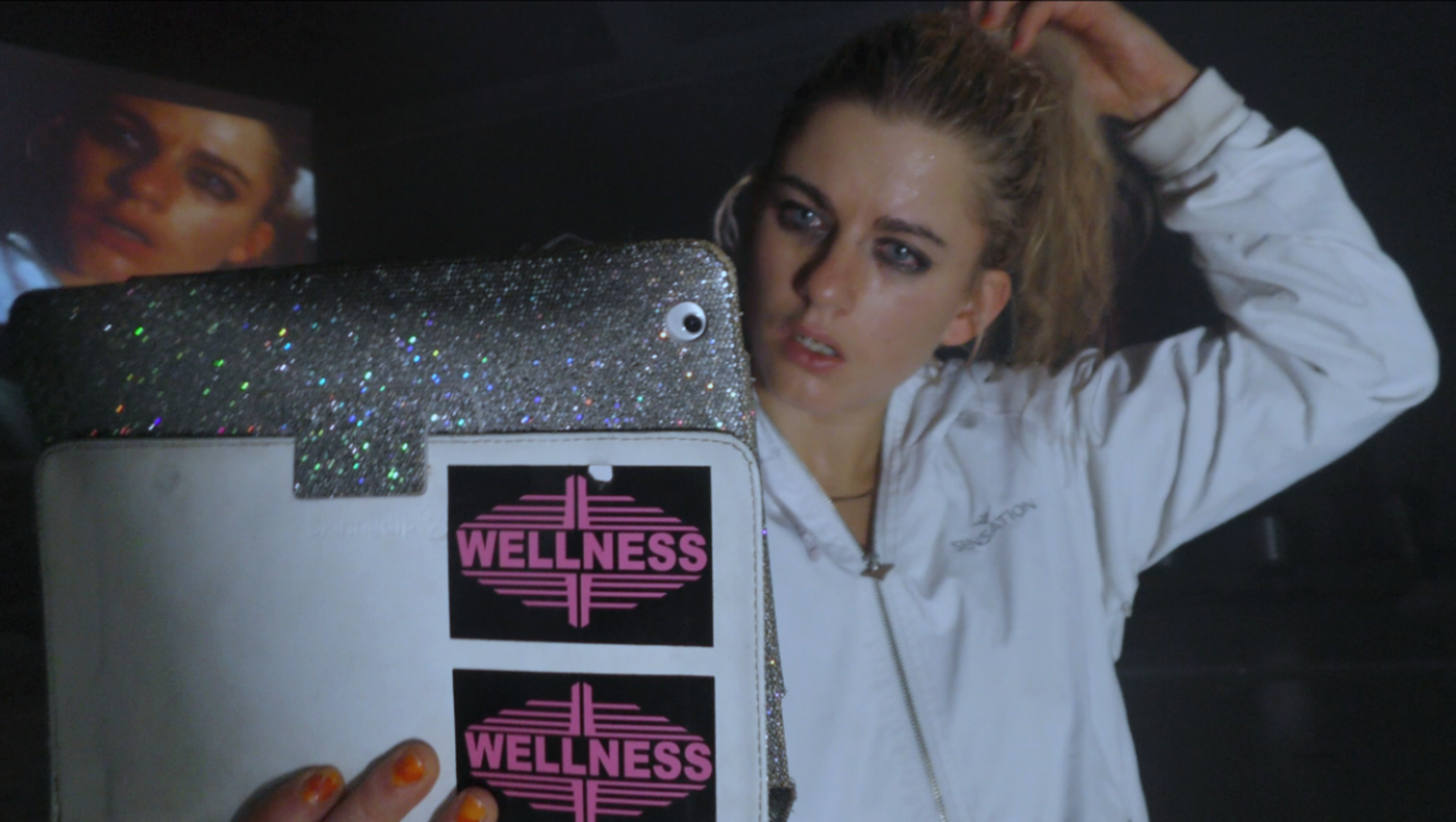

The second influence for the performance was the freak shows on Coney Island. I observed that American side shows are pretty similar to body-art experiments of the 70s, and I found this link intriguing since the only real difference is that one claims that what they are doing is art, whereas the other is proud to call their acts pure entertainment. I always find myself torn between those extremes, so I really wanted to assemble a 'freak show' cast to be my muses. To put together my Apollo side show, I was looking for acts that would be three things at once: funny, dangerous and disgusting.

VD: I think you nailed it. Most of us couldn’t quite make up our minds on how to feel about certain acts most of the time. It was a constant mix.

FH: Good! By default, these acts tend to question female performance historically and presently. I looked for my muses internationally and then, once I found them, we departed from classic side show acts to combine them with some of my wildest dreams. I also researched practices related to side shows, such as stunting or strong-woman-acts and weightlifting. I've done a lot of martial arts training and it was important to put my cast through some sort of warrior training so they would be strong and fearless and not give a shit in an intelligent way.

Topics like body cultivation or fitness are intrinsic to the imagery of Apollon Musagète ; you can’t talk about dance without talking about body cultivation. I have always enjoyed being very transparent about portraying trained bodies on the stage, the fact that they are manipulated, and how. So the show both attacks and advocates traditions such as ballet.

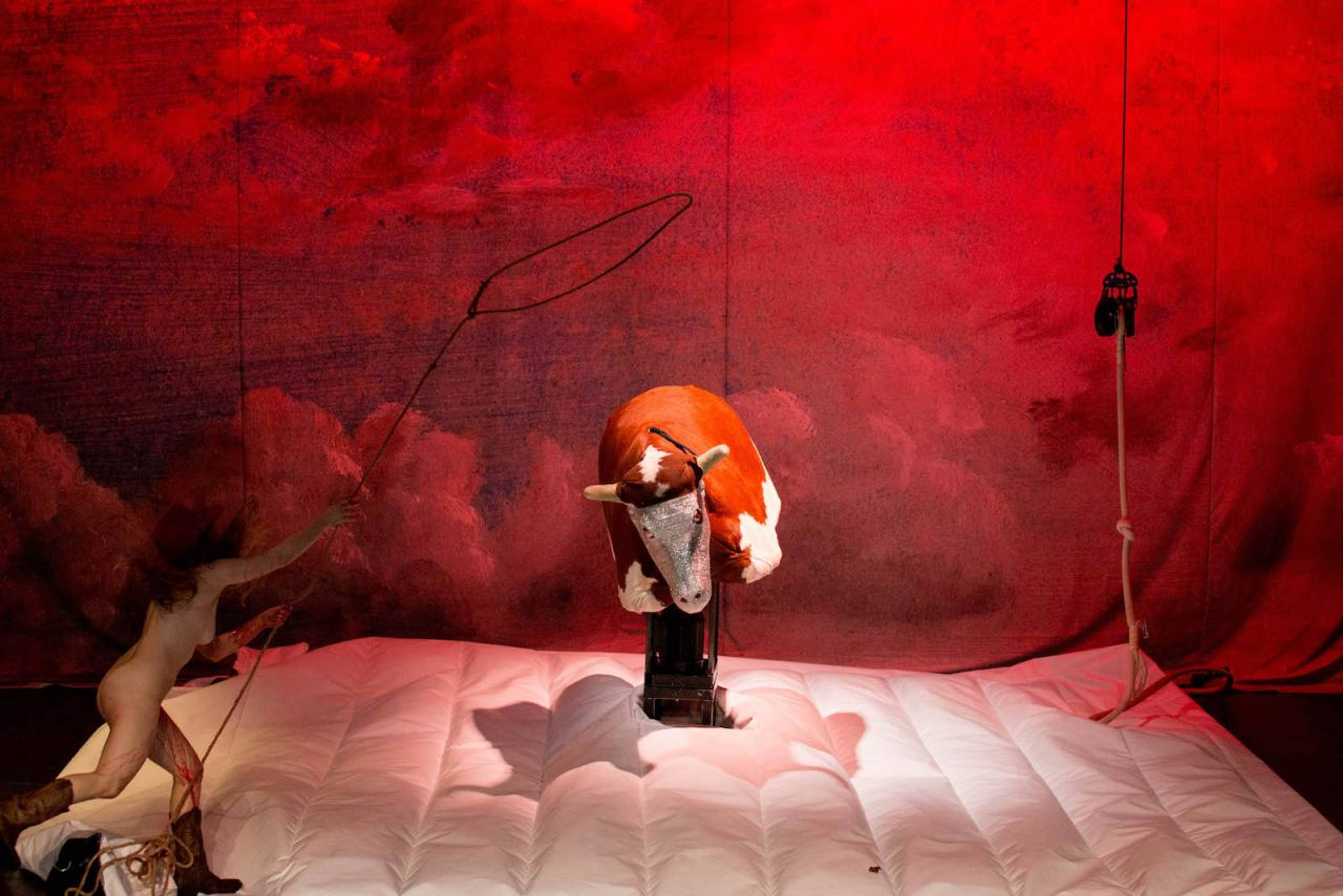

All images: Florentina Holzinger, Apollon Musagète, 2018. All photos: Radovan Dranga

VD: Can you tell me more about your interest in portraying these trained or manipulated bodies?

FH: Before I got into side shows, I made long excursions into stunting, which really relates to what interests me in theatre and performance and how people read my shows: What makes a person watch and experience? People clearly stand in for the actors – the ‘stars’ – and get barely any recognition, although they're often risking their lives. They have a capacity to use their body as special effect, powered by life energy and a certain desire to transcend, and that's clearly the relation that I have to my body in performance as well. It’s also the aspect that interests me in other people’s bodies in general. But don’t get me wrong – I was raised in a strong tradition of harmonious connection between the mind and the body. Maybe that’s why I was always attracted to the idea of the body being completely dissociable.

"I wanted people to be uncertain – like, 'Where the fuck did I end up?' – and for them to assume that there are no boundaries, which to be honest, there are none."

VD: Can you elaborate on what you mean by your upbringing in the tradition of the connection between body and mind?

FH: My school, the School for New Dance Development in Amsterdam, had a reputation for being very ‘new-agey’, meaning that they introduced a lot of concepts contrary to the Western dualism of body and mind that we see, for example, in ballet. In classic ballet technique, the dancer’s body and movements are strictly standardized and the body has to conform to a certain ideal shape. The dancer has no alternative for their own conception of the dance; they fail when they cannot fulfill the form. My education was contrary to that. It was much more about observing the body in a state of ‘becoming’ – in a unity of body and mind. There was a huge emphasis on the concept of ‘presence’. All of that was pretty mystical and exciting, but I was also often frustrated by the huge mystery of embodiment that would give subjective value to the dance. This led me to seek refuge in more ‘measurable’ physical practices that were not about creating unity but rather allowing the body to not think for a second, to treat the body as an instrument, an object that one can control and play. Nowadays my work and work ethics are hugely influenced by both concepts.

VD: Going back to what you said about combining your experiences with your wildest dreams: you're eating one of the performer's faeces on stage. Did you see Xana [Novais] live or did you come across her in your research?

FH: I met Xana in Porto, in a kind of contemporary circus show, where I saw her shit for the first time – pun intended. ( laughs ) It wasn't that I thought it was so great at the time, but it lingered in my head, not even as a memory but as a feeling. I felt her performance and thought to myself, “I don't remember the last time I saw something on stage that made me feel anything”, so I knew to take this seriously. I did my research, we connected on Facebook and I flew her over to Berlin, where I kind of auditioned her. Feeling-wise I knew right away that I wanted her. I immediately respected her skill. I could smell there was a regime and hard-core training behind her and I’m a sucker for both. I knew there was more to her than just the act itself.

"I’m opposed to the idea of auditioning. I believe in finding people or them finding you for the right project."

VD: And you and Annina [Machaz] go way back ...

FH: Yes, we are total blood sisters. We love to do the most boring things together like watching serial killer or conjoined twin documentaries while everybody else goes out to party and seek reproductive activity. Annina inspired me to create a utopia for Apollo where men don't exist. She is one of many female friends I have that are just ‘too much’ for most men. In the show she plays Calamity Jane and the aim was to create a safe space for Calamity to be herself. She likes to catch animals with her lasso, play with traps and knives, and she mutilates herself in a playful way. She tries to teach men that they don't have to be scared of her, that she is just a woman with an excellent sense of humor and that she primarily protects them from their fears. Funny women are very scary for a lot of dudes.

VD: How did you meet Renée [Copraij], Evelyn [Frantti] and Maria [Nüganen]? Did you audition them?

FH: Generally, I’m opposed to the idea of auditioning. I believe in finding people or them finding you for the right project, and usually magic and coincidence do their parts and they do their parts well. Renée and I actually met when she was my teacher at school, so we have a classic student/teacher relationship and it has been so nice to randomly switch those positions. We really have investigated what it means to transfer knowledge and experience from woman to woman– this means a lot to me in the work, too.

I cast Evelyn for the show – and again, I am against the idea of casting, but I was too curious about what would happen if I put an open call for ‘an extraordinary woman’ on Craigslist. In response I got a lot of Craigslist dick pics with surprisingly small dicks, but then Evelyn showed up. I met her and she was a fucking professional, and then I saw it all in front of me: how the show would come together and what the landscape would be. I dreamed about us being a backdrop for Evelyn during the entire show, just being her decoration. In the end it didn’t turn out like this – we hand the focus around – but those were our first rehearsals.

VD: And Maria?

FH: Netti [Maria] was my student in choreography school, so again we had this student/teacher relationship. I knew she was a no-bullshit-hard-worker and I was looking for someone to be my training buddy, somebody who would eventually be able to lift more weight than me. She is an Estonian Viking, our Brunhilde.

"Dynamics between choreographers and dancers, especially with opposing genders, are easily problematic, as there is always a power structure present"

VD: Did anyone have issues with your vision?

FH: Most people know what to expect when they work with me – that’s what I mean, I feel like people usually choose to work with me rather than me choosing them and this makes a lot of things easier. I need them to trust me unconditionally, to be passionate about what they do, and ultimately to be totally committed to the project. I make it clear at the beginning that I don’t have working hours and don't like to look at the time, but I am also flexible when needed or requested. I say I was looking for extraordinary women, but ultimately I just wanted to work in an uninhibited climate and with serious and disciplined workers.

VD: By switching roles and replacing Apollo with a female character, there seem to be many very powerful moments of deconstructing male dominance. Your dismantling the bull almost moved me to tears. The symbolism is so powerful and overwhelming. What moments had a tight script and what sprouted somewhat spontaneously out of the collaboration on- and offstage?

FH: To be honest everything sprouted from the collaboration on- and offstage. There were certain ideas or images I started with, but they were very vague. Initially I wanted to use angle grinders and a lot of chainsaws. Those are classic tools used in side shows, because they are loud, scary and dangerous, and I thought they would support chaos and actually scare people. I wanted people to be uncertain of where everything was going right from the start, to be on their toes from the first second – like, “Where the fuck did I end up?” – and for them to assume that there are no boundaries, which to be honest, there are none. If done with care and love, anything is possible. Maybe I should point out, though, that none of us are suicidal, extreme masochists or sadists; we are all just professional performance geniuses, like most women I know. ( winks )

VD: What are your thoughts on the sexual assault and harassment scandals popping up like whack-a-moles these days?

FH: This has been an issue in contemporary dance that was always talked about behind closed doors. Friends give jobs to friends, lovers to lovers ever more so – this openly happens all the time, but that's different because now we are talking about sexual assault and harassment. In dance, this is way more complex and trickier to trace. We are dealing with the body and we come from a history where dance was put on a similar level as prostitution, as we can see in early ballet. The patrons of the ballet got sexual rewards in return for sponsorship and traces of this dynamic still exist in major ballet companies. The dancer's body being exhibited is always a sexual object, too. I find it very important to be aware and not too naïve of that.

A lot of schools project a kind of neutrality on dance that we all know from contact improvisation: We all touch each other everywhere, but it is always non-sexual and consent is the professional duty of the dancer’s body. The “I'm not touching an ass for my pleasure but I'm manipulating a pelvic bone in time and space for my choreographic interest” dance paradox, however, can be very ignorant. Dynamics between choreographers and dancers, especially with opposing genders, are easily problematic, as there is always a power structure present. The dancer needs to ‘trust’ their choreographer to not abuse the role or cross personal physical borders, but conventionally, as a choreographer, you are supposed to fall in love with your dancer. In Apollon Musagète, I was seriously trying to find my muses – women that inspire me, that I could fall in love with.

VD: So how are you confronting or dealing with this paradox?

FH: The combination of young ambitious females and powerful men with authority has proven itself time and again to be profoundly flawed and lately what occurred to me was: What is this role in which women often submit themselves to this kind of dynamic? Why do they make themselves dependent so easily? Here I am also talking from my own experience in collaborations and I am becoming a bit radical just by deciding that I don't want to be bossed around by a guy ever again. In the work, that’s why it was really important for me to set up an interconnected network of females that support each other and move together towards developing a stronger stance. I also explicitly advocate a strong female body, because I believe that we have to be ready to fight for what we want and defend ourselves, and ultimately not be scared – physically and mentally. One of my aims is to really be able to trust one's own body as a force and weapon, in order to gain power to make the right choice.

___

Apollon Musagète is a production by CAMPO in coproduction with Münchner Kammerspiele, La Bâtie, Festival de Genève, Frascati Productions Amsterdam, Steirischer Herbst Graz, Künstlerhaus Mousonturm Frankfurt, and Sophiensaele Berlin.