I first became aware of Alicja Kwade (*1979) in 2019 when I temporarily landed a studio five minutes from hers, in Berlin. Walking by her huge space almost daily, I’d catch assistants polishing surfaces outside her studio in the sun. Even at a glance, her work was all precision – of materials, of their transformation, and of her process’s clarifying surgicality. Six years later, I find her walking me through her first solo exhibition in Belgium, at M Leuven. “Dusty Die” brings together extensive sculptural works, such as WeltenLinie (WorldsLine, 2019/2025), a room-filling mirrored installation embedded with stones, and ParaPosition (2024), in which a massive stone hovers above a chair that visitors can sit in, along with smaller, clock-ful pieces such as Gegen den Lauf der Zeit (Against the Flow of Time, 2021/2025). Whether static or kinetic, the watchword is tension – including, how forms somehow fix movement through sound, rhythm, and the return of recurring ideas. Our conversation started in the dark, surrounded by the first multi-channel iteration of her 2014 video In Ewig den Zufall betrachtend (Forever Contemplating Change), watching dice fall endlessly through space.

Michaela Schweighofer: Even before we see your work at M Leuven, we hear it: Standing at the entrance of the exhibition’s first room, which is completely dark, we catch a steady hammering, like stone or metal being struck, as if we can hear the production of sculptures we’re about to see.

Alicja Kwade: Yes, sound has always been part of my work. I started with video pieces years ago, mostly out of necessity – when I was a student, video was the only medium I could afford and which I had access to. I never considered myself a video artist, but I used the camera to film objects, and those objects would make noise. I’ve never used pre-recorded or artificial sound. It was always the sound of the material itself – stone, metal, clocks – usually repetitive, rhythmic sounds. Later, I tried to translate that feeling, the sense of motion, into sculpture.

MS: I can totally see that in your exhibition. At one end of the first floor, there’s Nach Osten (Eastwards, 2011), a swinging lightbulb swish-swooshing through the space. Then, on the exhibition’s top floor, there’s Hubwagen (Forklift, 2012/2013), which is moved in slow circles as part of a durational performance, producing a rhythmic clac-clac-clac each time it strikes the concrete tiles. I kept noticing these circular motions – of the clock, the mobile – and found myself thinking about hypnotherapy, where repetitive movement or sound can bring on a trance-like or meditative state. Is there a connection there?

AK: Not consciously. It’s not about therapy or hypnosis. For me, it’s about rhythm, and being alive in a system of repetition. It’s part of our lives, of our internal rhythms. I think that’s why it feels hypnotic.

Alicja Kwade, In Ewig den Zufall betrachtend (Forever Contemplating Chance), 2014. Installation view, “Dusty Die,” M Leuven, 2025

Alicja Kwade, Hubwagen, 2012/13. Performance view, M Leuven, 2025

MS: It’s interesting how your themes also seem to both literally and figuratively circle back – how certain forms or ideas reappear over time. I’m thinking of your work In Circles (2012), with slightly bent objects arranged in rings and a white door placed near their center; it reminded me of the radial composition of found objects in Tony Cragg’s Spiral (1983), which I saw in Antwerp two years ago. That white door reappears two years later, transformed into a logarithmic spiral in Eadam Mutata Resurgo (2014), whose Latin title is translated as “Although changed, I arise the same.” That’s so beautiful. Do you see your work evolving cyclically? Do you intentionally bring back older forms and ideas?

AK: Not intentionally, no. It only really hit me in 2015, when I had an exhibition, “Nach Osten” [at TRAFO, Szczecin], that included old video pieces and also a pendulum. That was the first time I realized my work had a kind of internal logic or repetition.

I don’t think about earlier work when I’m in the studio. I focus on what I’m doing now. But seeing those older pieces together, I had this moment of relief – like, okay, this all makes sense, even if I wasn’t aware of it. Especially in the early days, when you’re unsure, trying out different media – it all feels chaotic. But looking back, I saw there was a consistency. Whatever I’ve made in the past is part of me, so it comes back on its own terms.

Sometimes, I think, maybe this one object is enough – maybe the full story doesn’t need to be told every time.

MS: It seems that also some of your other objects, which originally appeared as parts of larger installations, later reemerge in different contexts. How do you think about the relationship between your installations and the individual sculptures that sometimes grow out of them?

AK: I never take an existing installation apart – they always remain as they are. But over time, I might feel that a single one of its elements carries the essence of what I wanted to say, and I’ll isolate it, by duplicating it in a slightly altered form, while leaving the original be. Whereas sometimes, I think, maybe this one object is enough – maybe the full story doesn’t need to be told every time. It’s not about simplifying for the sake of Minimalism, but about distilling the work down to its clearest form. I want to say just one sentence, not a whole paragraph, because I am trying to get to the point. So, I select, reduce, focus.

MS: That’s interesting – because as a viewer, I had the impression that objects were being pulled out of installations. But they’re actually preserved, and what we see are echoes, not fragments.

AK: Exactly.

MS: What you mean by “select, reduce, focus”?

AK: I want the form to be precise, to contain only what’s necessary. If I polish something, I want it to be so polished that it almost disappears. I don’t want to see any tool marks or traces of how it was made. If a piece has too many elements, it usually means I’m unsure. It’s like when people talk too much because they’re insecure. The object should exist on its own terms, like it simply is.

MS: Is that something you also try to teach your students?

AK: Not necessarily. It’s not about telling them to be minimal or formal. For some people, the chaos is necessary – it’s part of the work. What matters is awareness. Knowing what you want – or knowing that you don’t know – that’s already progress. Being able to speak about your work also helps. when I talk to students, I really pay attention to how they talk. If they’re unsure, they tend to over-explain, and that’s often a clue. Not everyone has to, but exhibiting means working with other human beings, and if you want to be seen, you have to communicate. Being clear, even about uncertainty, is important.

Portrait of Alicja Kwade, 2023. © Doro Zinn

MS: That clarity was very present in the tour you led of the exhibition, but there was one piece you didn’t mention and which I almost missed: Wo Oben zum Unten (Where Up Becomes Down, 2015), a set of keys that, attached to the ceiling, loom overhead like a tarantula. It feels different from the other works, and I don’t think I’ve seen it before.

AK: It appears from time to time. The work is symbolic – people can see what’s there and how it was made, but the context, the emotional reality behind it, remains private. That’s intentional. In contrast to the clarity of my work, I’m actually quite messy in life. I lose things constantly – especially keys. Over time, I ended up with a bunch that I didn’t know what they opened, not knowing why I kept them. You hold these keys, these possibilities, but you don’t always find the right door. They could open something, but even I don’t know what.

MS: So maybe they’re a stand-in for future works – potential doors waiting to be opened?

AK: Exactly. Or you might never find the door.

AK: Yes. I was naïve to think I could cut myself out of my work, as if the two had nothing to do with each other. You can’t step outside yourself. So, that’s changed – I’ve come to accept that my life and experiences inevitably shape the work.

MS: You’ll always be the person making the work, and there is a certain insincerity in not admitting to that.

AK: Personally, I’m much more interested in what people do, in who they are in the moment, than in where they’re from or what their background is. I don’t get emotional about someone’s country of origin or what their parents did. What draws me in is presence. So, when it comes to my own story, I sometimes think, why should I share it? Sure, I’m from Katowice, I was raised in Poland – but mentioning that can lead to interpretations I don’t want or need. I want the work to speak for itself.

I avoid overly designed pieces that bring too much of their own meaning. I want objects that are archetypes, that are almost invisible in their familiarity.

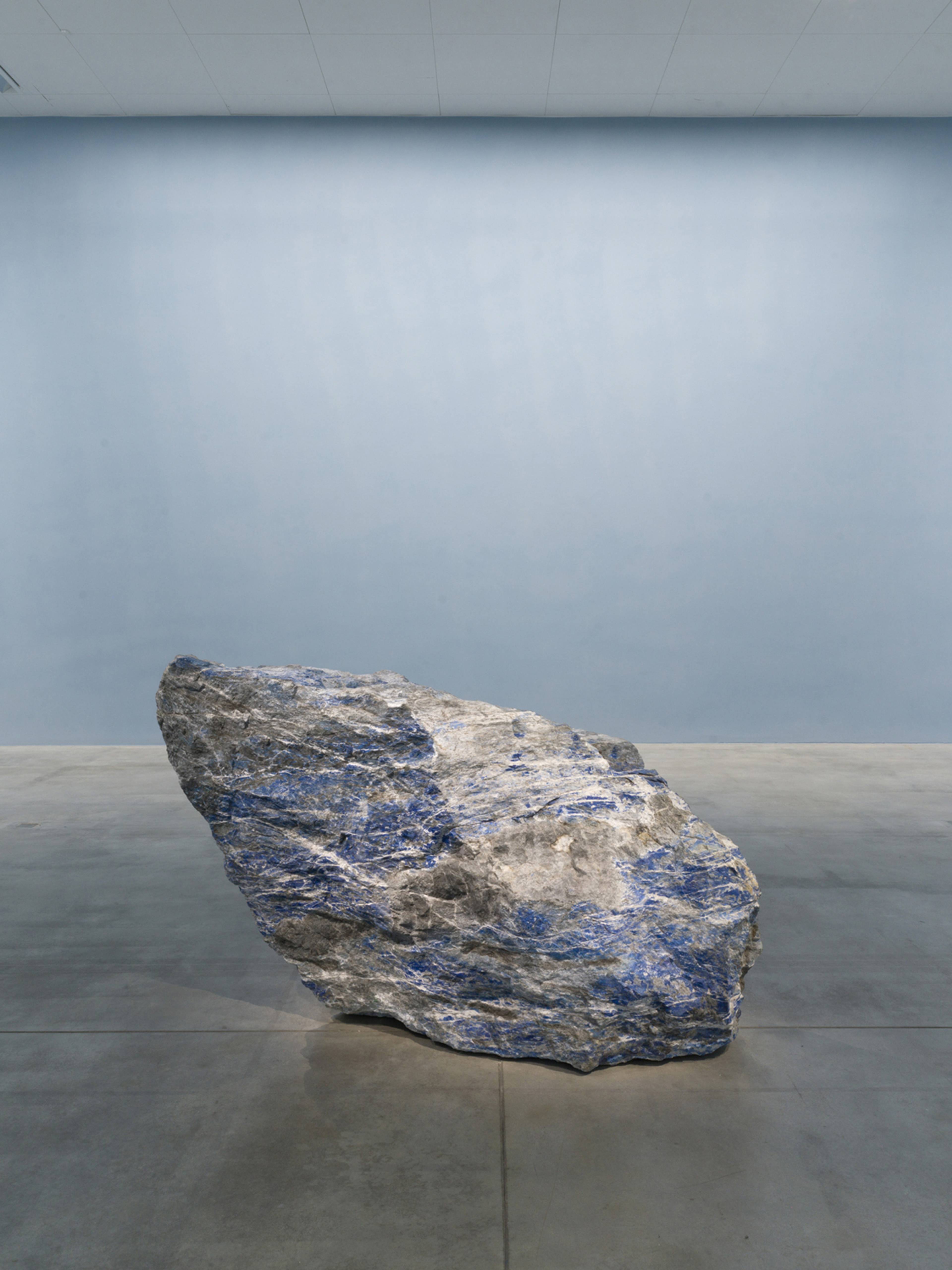

MS: That’s interesting. Because with students, it’s often the opposite – they start by being too personal, and as teachers, we try to guide them toward something more universal. I like that your journey kind of flips that – starting with distance, and over time recognizing that some of you inevitably comes through. Your practice seems to be very relational – not just in how you work with your studio team, but also with outside collaborators, like the stone masons who helped source materials, such as the massive lapis in Blue Days Dust (II) (2025). Was that collaborative aspect something you always envisioned, or did it evolve naturally over time?

AK: It just happened. Honestly, I never planned to have a big team. it just grew with the projects, mainly through public commissions, which I really wanted to do. I believe in public art, I believe that it matters, and for that, you need engineers, architects, fabricators …

I love my team – we work incredibly fast, and we’ve done things I never could have done alone. But sometimes, I even see it as a failure, like something that got out of control. I still need solitude to work, and that only gets harder and harder. At one point, I tried limiting team hours – no one in the studio on Fridays, or everyone out by 4pm. I’ve given up on that now. It is what it is.

MS: Your sculptures also feel relational – like the chairs you use. They’re not just objects; they imply a social situation, like sitting together. They carry human relationships.

AK: Yes, exactly. I’m drawn to common objects: things everyone recognizes, like a simple, old-fashioned cafe chair. I don’t use them for symbolic reasons; it’s just that, when I imagine a chair, that is the chair I see in my head. I avoid overly designed pieces that bring too much of their own meaning. I want objects that are archetypes, that are almost invisible in their familiarity.

Behind: Siège du monde, 2025, painted stainless steel, Azul Macaubas; foreground: Superheavy Skies, 2025, mirror-polished stainless steel, stones

Alicja Kwade, Blue Days Dust (II), 2025, lapis lazuli, paint

Alicja Kwade, Eadem Mutata Resurgo, 2014, wood, patinated brass, acrylic paint

MS: Recently, you showed the installation Telos Tales (2025) at Pace gallery in New York, where your clocks made a re-appearance – but, I’d say, in a more atmospheric and intricate way. You put them into tubes levitating from the ceiling, with bronze branches growing all around them, which almost erupted into the bronze burrows titled Unearth (2025), as if one work had grown out of the other. It definitely felt like a shift from your earlier clock works.

AK: Yes, but that wasn’t planned. The series began with a land art project I was working on in New Mexico. The idea was to pierce an entire mountain with a polished stainless-steel tube. And even though the project has unfortunately died – it turned out to be super complex and expensive, with geologists and permits and all that – I became obsessed with the tube as a form. It became symbolic – like a cut-out of the present moment. I had this stone in my studio pierced with a similar pipe, and one day, when someone walked behind it, it created this incredible visual effect. So, I told my assistant to print out a clock face, and we slid it inside. It looked amazing. Then, we tried a real clock, and I realized the tube was amplifying the ticking. It worked like a giant speaker. The branches came from another strand in my work – thinking about trees, systems, engineering structures. It all just merged.

MS: It’s a blend of past, present, and future works, with a touch of serendipity.

AK: It’s important to leave space for those surprises. Even if my team hates it. [Laughs]

Alicja Kwade, WeltenLinie (WorldLines), 2019/2025, powder-coated steel, mirror, bronze, patinated bronze, stone, petrified wood

MS: During your tour of the exhibition, you mentioned how visitors tend to avoid certain pieces instinctively, almost superstitiously – like ParaPosition (2024), a large-scale installation with huge stones looming above and a chair beneath. It reminded me of walking under a ladder – of bad luck, but also an actual risk. Do you consciously play with that tension between magic and physical danger?

AK: Absolutely. I grew up in a very Catholic environment in Poland, surrounded by saints and relics and all this mystical stuff, but there’s something universal about the response trigger. Having a huge stone above your head triggers a reaction: most people avoid the stone; others hug it. The individual’s reaction is what I’m interested in.

MS: A lot of times, the surface of your work is so polished as to become an object of fixation. Do you try in any way to work against that obsession with perfection?

AK: Sometimes. But I also don’t intentionally add imperfection. What I love is the ambiguity – that someone might look at the work and has no idea how it was made. There’s so much digital work in my process, like 3D scans, modeling, but it’s all hidden. You’d never know, which adds to the magic.

To take a simple example, like the mirrored stones I make: I scan a rock, flip the image, adjust for bronze shrinkage, mill it slightly bigger and in a different material, and cast it. Then, I place a mirror so precisely that the reflection perfectly overlaps. People often think it’s a screen, but it’s just geometry. I love that moment when someone realizes what they’re seeing – and doesn’t know how to explain it.

MS: I had that experience with the mirrored stones in your installation WeltenLinie (2019/2025) – I wasn’t sure which side was real. There’s a kind of magical horror in that moment, a disorienting uncertainty, like stepping into a hall of mirrors on the haunted side of a funfair.

AK: Exactly. That’s what I’m after. That moment of not knowing – when reality shifts just slightly enough to feel strange. That’s when the work becomes alive.

___

Alicja Kwade

“Dusty Die”

M Leuven

10 Oct 2025 – 22 Feb 2026