Ann-Sofie Back is fickle, direct, and doesn’t suffer fools – not least herself. She is an unusual Swede: typically preoccupied with what others think, yet non-conformist to a tee. Described by Vogue as “the number one enfant terrible of Scandinavian fashion,” there was a softly spoken lore to the world in which Back dwelt. She is sensitive and observant, careful and careless.

Very few creative Swedes become famous. Those that do tend to have outsized influences on the territories they inhabit. Think ABBA, the rapper Yung Lean, the Skarsgårds (pick one), the filmmaker Jonas Åkerlund, Greta Thunberg. In her own way, Back sits among this muddled bunch of unlikely icons. Raised in Stenhamra, a Stockholm suburb, she left 1990s Scandinavia to enroll in London’s Central St. Martins. Although her eponymous label, BACK, is not a household name, during its two-decade-long lifetime, it challenged all conventions, catching the eyes of street teens and worn by the likes of Beyonce, Björk, and the Spice Girls. During this time, her pieces were shown in other contexts, such as the V&A and the Palais du Tokyo. Not long after the label went bankrupt in 2018, Back left mainstream fashion to start gnilmyd kcab – a maker of interior accessories – alongside Mattias Dymling, and has just donated her private archive of printed matter to Oslo’s International Library of Fashion Research.

With a name more well known in London or Paris than in her native Stockholm, Back has sought to quite literally bury her own career as a fashion designer in a monographic exhibition at Liljevalchs. “Go As You Please,” which lifelessly presents celebrated archival pieces spanning 1998 to 2018 in satin-lined coffins or affixed to a sea of singed, faceless mannequins, is a tongue-in-cheek middle-finger to the industry that made her famous – and the city she once rejected. Object labels are presented as garment tags, fashioned as obituaries. At the exhibition’s vernissage, attendees – including a raft of fashion-world heavyweights – were handed white flowers to lay on the gallery floors.

james taylor-foster: “Go As You Please” – where does the exhibition title come from?

Ann-Sofie Back: It’s a funeral parlor somewhere in the UK. I think I saw it on Instagram and thought to myself – this sounds like a dress code, as well as a death code. “Go As You Please” is not dissimilar to “Come as you are.”

jtf: And this was the inspiration for the exhibition?

ASB: I tend to be inspired by things that I’m uncomfortable with. And, since 2021, perhaps, many of my relatives have died. My dog died. I got cancer. I just find death to be really embarrassing.

jtf: Why?

ASB: It’s just so uncomfortable – funerals, that is, and dealing with people’s houses. I’ve now death-cleaned myself, even long before I felt like I was going to die. I think it was around the time I had to liquidate my company; it was all very depressing, and I didn’t know who I was any longer.

View of “Go As You Please – Ann-Sofie Back 1998–2018,” Liljevalchs, Stockholm, 2024–25. Photo: Mattias Lindbäck

View of “Go As You Please – Ann-Sofie Back 1998–2018,” Liljevalchs, Stockholm, 2024–25. Photo: Mattias Lindbäck

jtf: I’ve come to appreciate this very Swedish behavior of dödstädning – death-cleaning. The idea is that, not wanting to be a bother to your nearest and dearest, you self-organize your clutter and wait out your final weeks, months, or years in a form of domestic minimalism, driven by shame. What did you discover through the process?

ASB: The whole thing is a little bit of a blur, but around 2019, I just came to the realization that I had to get rid of all my old love letters, all the embarrassing photos I had accumulated, and so on. I thought to myself: “Imagine if someone comes and actually sees this shit ….”

jtf: Now I’m curious!

ASB: There’s nothing left. I didn’t even dare to throw it in the trash. I burnt it all.

jtf: You burnt it?!

ASB: Yes. I’ve never thought about death that much; I’m not a hypochondriac or anything. It was just the weight of having to deal with stuff that overwhelmed me. I think that lots of people misunderstand me. I take what I do super seriously, but I also don’t take it seriously at all. And most people can’t handle those conflicting feelings. It makes them confused and uncomfortable, and it makes me uncomfortable as well. The difference is that I’m choosing to live with the conflict, so to speak.

jtf: What do you want your funeral to look like?

ASB: I’ve seen those gangster funerals in the East End of London, and that looks pretty good to me. Closing off the whole high street and filling it with horses and carriages and people. They feel dignified, and less repressed than the average Swedish funeral.

jtf: Your exhibition is, to all intents and purposes, a funeral. But what is it a funeral for?

ASB: My label, I suppose. Initially, I worked hard to have a business that worked and, at some point, I started to sell things – which I didn’t necessarily expect, even if it was something I wanted. I ended up spending time doing precisely those things I never wanted to do, like getting involved in the practicalities of running a business and employing other people to help, which just becomes this pointless cycle.

Ann-Sofie Back, AW04, London Fashion Week. One Time Only publication. © catwalking.com

Ann-Sofie Back, AW04, London Fashion Week. One Time Only publication. © catwalking.com

Ann-Sofie Back, AW04, London Fashion Week. One Time Only publication. © catwalking.com

jtf: Now it’s been laid to rest! Do you think that a creative practice can also be a functioning business, or is something of the former inevitably lost?

ASB: In the end, I became bored of trying to make a business that worked. In the field of fashion, PR is eighty percent of the job, and design becomes something like five – the other fifteen is I don’t know what. Eventually, I had people working for me who had no idea who I was, and I kept on having to explain things to them, again and again. If the company was criticized, they would get scared, and I wound up having to manage that, too. I’d constructed an identity that was entirely separate from myself, while also being completely tied to me.

jtf: That sounds rather exhausting?

ASB: When it’s going well and there’s a consensus, it’s all good. As soon as there’s a dissenting opinion, it all of a sudden becomes a personal attack.

jtf: Do you have an example?

ASB: We once had to do a super-cheap shoot, and we had someone working for us who we asked to model for it. I won’t go into all the details, but I dressed her in a plastic scarf. Someone interpreted the photographs as though we were suffocating her, and it became a huge thing on Instagram. Someone reported us to some organization representing ad agencies, and we were found “guilty” of being derogatory to women, or something like that. But this was in Sweden, which has always been touchier than the UK.

jtf: What, as a Swede who has spent so much time and built their career abroad, is your relationship to “Swedishness?”

ASB: Nowadays, I’m very conflicted. When I lived in the UK, I felt very Swedish. Maybe it was because I grew up understanding that there is a sort of equality between the sexes – I mean, I’m a feminist. And that was something that no one in the fashion industry in the UK had heard about before. Now that I'm in Sweden, I don’t feel very Swedish at all.

Pop culture needs humor and rebelliousness, which, I think, are a very British thing.

jtf: You graduated from Central St. Martins in…

ASB: 1998.

jtf: It was a different moment – largely heteronormative in its presentation (or lack) of queerness and gender equality in media, for example.

ASB: Unless it was i-D magazine!

jtf: Right. There was a strange relationship to femininity, in a way. The first female icon I can recall is Diana – and she was a princess.

ASB: Yes. When did she die again?

jtf: 1997?

ASB: Yeah. Okay. You’re very young.

jtf: Getting on! As someone who grew up in the UK, I would say that your work has absorbed a certain strain of British humor.

ASB: That might be because Sweden was inundated with British comedy. I would say that I absorbed pop culture, of which comedy is a part. The likes of Paris or Milan don’t have pop culture – or not in the way that I see it, anyway.

jtf: How do you see it?

ASB: Youth groups and magazines, mostly. Now, they’re all so commercialized – it’s a different thing. Pop culture needs humor and rebelliousness, which, I think, are a very British thing. Living in London when I did felt like living at the center of the world. You could go to a party and end up at Liam Gallagher’s house.

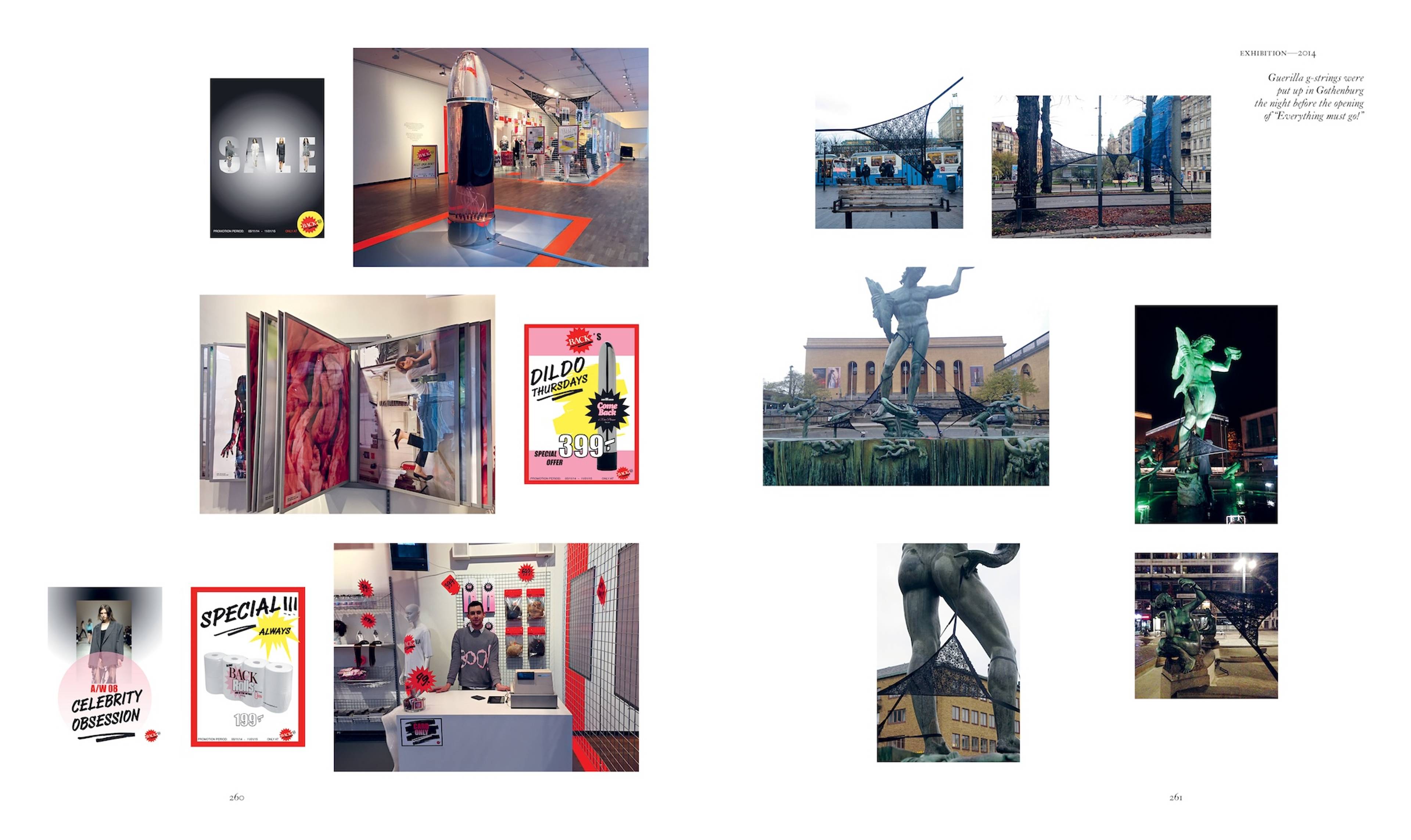

Guerilla g-strings were put up in Gothenburg the night before the opening of “Everything must go!”, Röhsska Museum, Gothenburg, 2014

jtf: Did you want to be famous?

ASB: No, never. I don’t want to talk to famous people. It’s fun to watch them …

jtf: … or to dress them?

ASB: God, no! That’s a fucking pain because it’s always all about them, and I’m simply not interested in them.

jtf: What are you interested in?

ASB: I’m interested in surprising myself by the ways I combine things or ideas. I mean, it’s nice to see Rihanna wearing a top of yours that she bought off-the-rack, but I’m not interested in meeting her and taking her measurements and catering to her insecurities. I love Rihanna, but I would never dress her for her sake. I’m doing it for me.

jtf: Do you think pop culture still exists?

ASB: You used to see something on a person on a street and think to yourself, “What the fuck is that?” Today, you see it on social media before you see it in real life. The mediation is completely different. But I’m also fifty-three, so I’m not sure I can answer the question.

jtf: Why?

ASB: Because I’m not curious about much anymore. And I’m not actively working on finding out about things, either. That sounds awful, but that's where I am now. Procrastinating.

jtf: Are you ashamed by the idea of a period of procrastination?

ASB: Shame is a big part of my practice. It stems from the fact that I was extremely ashamed of my parents, and my mum was someone who wasn’t ashamed of anything – something which is extremely embarrassing if you’re Swedish. She was a pain in the arse, to be frank. My adopted dad was a conformist – someone who didn’t want to stick out in any way. He had two successful siblings, but he had no desire for a career himself. I remember us going to his family’s place for dinners and having to deal with the painful situation of my mum talking about feminism or nuclear energy or something. [Back’s father and his sister worked in nuclear energy.] She just had to bring it up; it had to be discussed. I hated her so much for doing that. To me, fashion and shame have always been intrinsically linked – probably, staying with my parents, because of their complete lack of interest in how they dressed.

jtf: It’s interesting how you use the word “pain” together with “shame.” It reminds me of Ragnar Kjartansson’s sculpture Scandinavian Pain [2006] – a nod to Nordic melancholy, presented as an advertisement. Perhaps you’re talking about something similar: Scandinavian shame?

ASB: I’ve held these feelings together since I was thirteen, when I’d walk around wondering: Is everyone else feeling this, too? At the time, however, my parents didn’t care what I did. I could have been a waitress or a nurse or anything and they wouldn’t have minded.

Backstage SS05. Photos: Anders Edström

jtf: Not even your mother?

ASB: My mother didn’t put her nose into what I wore or what I did as a job. I could dress up like a hooker when I was ten years old and head off to the supermarket, and she would say “Oh, you look nice. No pants. Have fun!” She put her nose into everything else, though, and I rebelled a lot. I threw things at them and called them names for years. But I never had to rebel against those two things.

jtf: The feeling of being abnormal is itself not an abnormal feeling, I guess. It seems to me that you haven’t been working against a feeling of shame, but rather working with it?

ASB: London showed me that there are many different groups of people, and that some people will just never understand you. There are multiple spaces where you can exist. In Stockholm, it’s a death sentence to have a feud.

jtf: Undeniably true! Is the Liljevalchs exhibition trying to put a nail in the coffin of a long history of feuds and collaborations?

My archive is being archived. The funeral is happening.

ASB: In a way, yes. My archive is being archived. The funeral is happening. Psychologically, I’m closing a chapter and trying to move on – even if I haven’t quite started to move on yet. Annoyingly, people keep wanting to order pieces that are on display.

jtf: Will you take on these commissions?

ASB: No way. I’m bored of replicating myself. It wouldn’t be worth the pain.

jtf: Are you planning to stay in Stockholm?

ASB: I’ve been thinking about that a lot recently. A friend just moved to Paris to work for a big fashion house, and I’m really jealous of them. I’m not sure I could survive financially anywhere but here, though. Isn’t that boring.

jtf: It’s refreshing to hear someone articulate jealously!

ASB: I know. Isn’t it shameful, though? Jealously is really ugly. I’ve become better over the years, but I am a very jealous person.

jtf: Do you get jealous about people or the things that people do?

ASB: Everything, but particularly things that I should have been smart enough to do myself. If I truly become jealous, it’s because I couldn’t have done the thing that someone else has. Because I’m not good enough.

Ann-Sofie Back. Photo: Alva Le Febvre

___

“Go As You Please – Ann-Sofie Back 1998–2018”

Liljevalchs, Stockholm

8 Nov 2024 – 23 Feb 2025