Assaf Gruber’s Miraculous Accident (2025) is a cinematic essay that narrates the love between Nadir, a Moroccan who has been invited to study filmmaking in Łódź as part of the Socialist Bloc’s support for anti-imperialism, and Edyta, his Jewish film-editing teacher. It takes as its backdrop the tumult and tragedy of 1968, when a diplomatic rift between the Bloc states and Israel resulted in the forcible expulsion from Poland of around 15,000 Polish Jews, many of whom had remained in Europe after the Holocaust because of their opposition to Zionism. When Nadir, played by the poet and filmmaker Abdelkader Lagtaâ, is notified of a letter written to him by Edyta from Haifa in 1989, he returns to the Łódź Film School – and brings the story of his love affair into the present tense. Weaving together original footage and extracts of films shot in the 1960s by Lagtaâ and his peers, Gruber’s work observes how the political intervenes upon life’s unlikeliest personal encounters.

Joanna Warsza: You are interested in speculative scenarios, the roads not taken, the unrehearsed art-historical and political course of events – what theorist Ariella Aïsha Azoulay calls “potential histories.” What is a potential, unfulfilled history behind Miraculous Accident?

Assaf Gruber: When I began researching the period that started in the early 1950s – when Eastern Bloc film academies such as the Łódź Film School, VGIK (Moscow), and FAMU (Prague) forged alliances with countries across North Africa, the Middle East, South America, and parts of Asia to promote socialist ideals through cultural exchange and film education – I realized there was a striking conjuncture in Poland’s 1968 history. The Soviet Bloc countries largely sided with the Arab world in the aftermath of the Six-Day War of 1967, or Naksa (“the setback”). However, Poland took it one step further, instrumentalizing the conflict to purge many Jews who had remained in the country after World War II, accusing them of “dual loyalty” to both Poland and the State of Israel. They justly saw themselves as part of Polish society, and yet were forced to leave. It’s this moment in the late 1960s and its entangled identities, with Arab students arriving to study in Poland just as Jews were being exiled, that Miraculous Accident brings forward, in a fictional yet entirely plausible love story between a Jewish editing teacher and her Moroccan student.

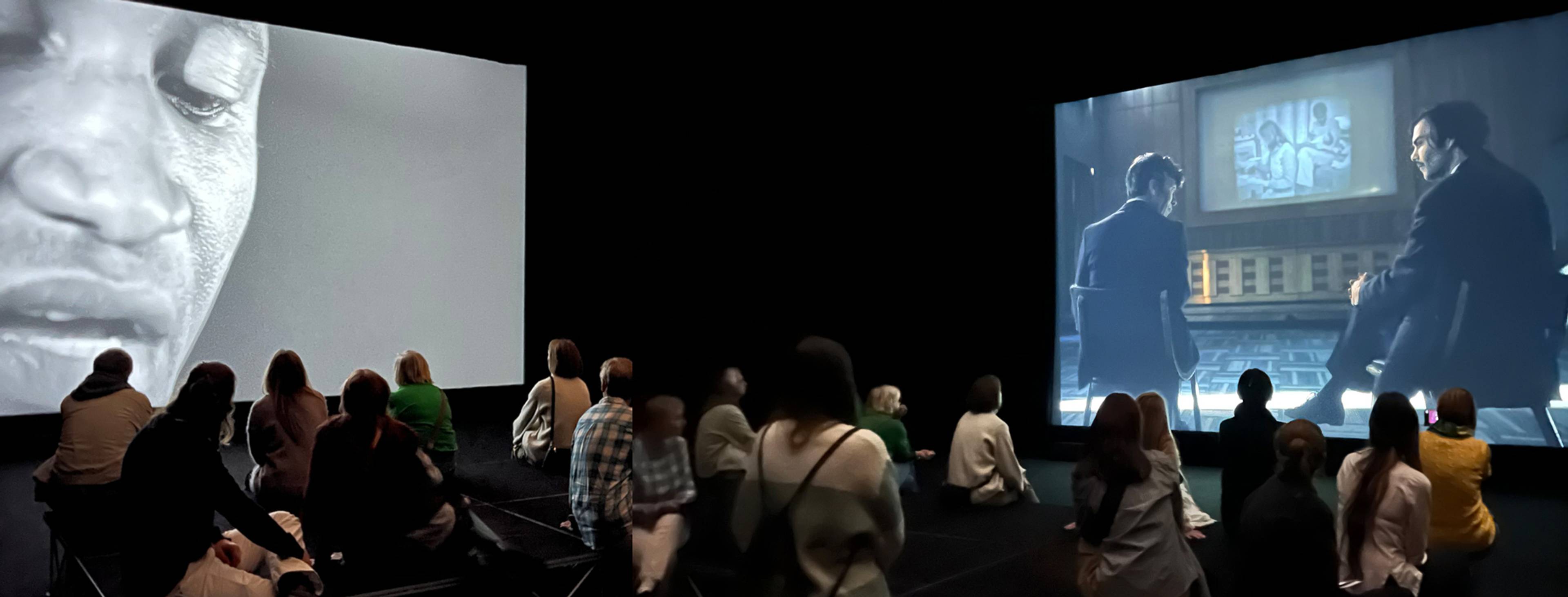

Stills from Miraculous Accident, 2025

JW: In preparation for the film, you spent a lot of time in the archives of the Łódź Film School. You used some of the footage you found there, and one of the films even inspired the opening scene and the outlook of the characters. Can you talk about this process?

AG: What drew me even deeper into this history were exactly those nascent films – works in progress created by foreign students who were complete outsiders in the contexts where they found themselves. Their films often reflected a sense of alienation, consciously or not, while also carrying within them their own countries’ struggles for independence.

It isn’t one specific film that inspired the aesthetic and narrative of Miraculous Accident more than another, but rather the filmmaker, poet, and visual artist Abdelkader Lagtaâ, who plays Nadir in the film, and with whom I conversed at great length during the writing process.

In terms of archival material, I can also refer to the film shown in the opening scene – Wait, Wait (1980), a documentary about the South African student-activist Patrick Mabinda and his Polish wife. It was directed by Beverley Joan Marcus, who was both the only female director from that period and the only Jewish South African filmmaker I came across in the archive. In Miraculous Accident, this film is reimagined as if it were directed by another key character, Jarek – Nadir’s best friend, as well as Edyta’s student and protégé.

Another reference is A Shadow Among Others (1969), directed by Abdelkader himself, in which an exiled activist receives a threatening postcard from rivals who have kidnapped his lover. These kinds of tensions, caught between personal intimacy and ideological battles, between being alien and dreaming of liberation, became central to Miraculous Accident.

Between the scripted scenes and the archival inserts, the whole film thinks and feels through the collision of Cold War ideologies. One of the main aims was to shift the lens toward Eastern Europe – a perspective rarely centered in discussions around the Arab and the Jew, to propose a different point of view for contemplating our inexorable present.

Stills from Miraculous Accident, 2025

JW: Abdelkader Lagtaâ, who plays Nadir, is silent throughout your film. How do the lives of Lagtaâ and Nadir intertwine? How was it to work with him?

AG: First of all, Abdelkader is one of the most extraordinary artists and personalities I’ve had the privilege to work with and know closely, and both his presence and his legacy had a profound impact on the film. In fact, the entire work is infused with references to his own autobiography, as many of the student films shown are either directed by him or feature him as an actor.

The only element that doesn’t come from his real life, but belongs purely to the character of Nadir, is his relationship with Edyta. In the film, the school informs him that it has uncovered a letter she wrote to him in 1989, which he feels summoned to read in situ, within the very walls where, as Edyta writes to him, their felonious affair once occurred. In some ways, her letter is actually based on my own responses to Abdelkader in the long conversations we had over the four years leading up to the film. So, even though he doesn’t act/talk to other characters, his oeuvre, his presence, and his way of being, I would say, speak loudly throughout the entire film.

JW: 1967/68 was a pivotal moment in Israeli, Palestinian, and Polish history. How can we locate its consequences in contemporary cruelties: the genocide in Gaza, extremism in Israeli politics, the conservative right-wing turn everywhere? Is 1968 the film’s backdrop as much as its link to our own times?

AG: We often like to blame Israel first, and then the West, with Germany and the United States in the lead, for this lethal cocktail that fuses Judaism, Zionism, and Israel into one indistinguishable mass. But in that particular 1968 segment of history, this cocktail was not created by Israel or the great powers alone. Poland (and, in other ways, the Soviet Bloc) played its part too, when it forced Jews, many of whom were not Zionists by conviction, to emigrate. For many, Israel was their only viable option. In that sense, Poland’s 1968 crisis offers a perspective that exposes a deep paradox: Those who refused the idea of Israel as an ethno-national state were exiled to it in the name of another. It reveals how easily political systems turn identity into a weapon.

And if you ask about today: a similar weaponization of national identity is being used by Israel, fueled by ideas of Jewish supremacy, to justify crimes against humanity. The only way to separate this cocktail’s poisoned ingredients is by exercising a collective responsibility – namely, by recognizing the tragic consequences that have come at the expense of the Palestinians and, by doing so, also protecting Israel from itself. When we fail to apply universal values to these deeply flawed political constructs, we simply repeat the same mistakes of the past.

After all those decades in which we believed we were preparing ourselves, we now realize, not through studying or reflecting on the past, but by living this present, how people in history so often became apathetic to the suffering of others.

JW: At the debut screening at the Berlinale Forum Expanded, you said that the film tells the history of Jews, Arabs, and Eastern Europeans without the mediation of Germany. What did you mean?

AG: Miraculous Accident, together with Miraculous Accident Part II, Nadir (2025), which is now on view at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw as part of the Kyiv Biennial, tries to tell this shared history without passing it through the usual Western frame, and especially not through the dominant German one. Instead, it unpacks this history from an Eastern, post-World War II perspective, looking outward to consider the triangle of the Arab, the Jew, and the European.

JW: You have been orienting yourself toward Eastern Europe generally and Poland in particular, often finding inspiration in what is called Weltschmerz in German – a feeling of pain, longing, and the burden of complexity in the world. Is this interest related to your family history? Why do you keep coming back to Poland?

AG: My family’s Polish side originally came from Lviv, which was then part of Poland, but they spent some years during World War II in Kraków, living under false identities. There’s a certain enigmatic predicament around my grandparents that I often return to – and it sometimes leads me into fictional territory. They lived part of the war as sister and brother until they were exposed …

What initially brought me to Poland, though, was a 2011 group exhibition in Nowy Sącz, curated by Adam Budak and titled “Passion of an Ornithologist,” which revolved around the Polish Jewish writer and painter Bruno Schulz. When I started receiving further invitations, I remember being quite persistent and clear in refusing to bring explicitly Jewish themes into my work, not wanting to be subsumed by that curatorial tendency. Instead, I wanted to tell Poland something about itself through my point of view. My video The Right (2015) is a good example. It was commissioned by the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź and tells the story of a Volksdeutsche woman – one of those ethnic Germans living in Poland who, beginning in 1944, were cast out and stripped of their homes for having been registered as “German” during the Nazi occupation. Working as a museum attendant at the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Old Masters Picture Gallery) in Dresden, she writes a letter of intent to the director of the Muzeum Sztuki, expressing her wish to volunteer at the Łódź institution after her retirement. It’s unclear whether her motive is a genuine fascination with the city’s early avant-garde a.r. group and their subversive approaches to life and politics, or simply a longing to return to where she was born.

Around that time, I found a community of artists and curators who were politically engaged in a way that was very different from what I had known in Paris, where I had studied. The scene in Poland in the late 2000s felt less driven by the market and more by ideas and activism. I became close friends with several artists of that generation, and that made my relationship with the art community here feel organic.

Assaf Gruber, Miraculous Accident, 2025. Installation view, “Near East, Far West,” Kyiv Biennial 2025, Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw, 2025

JW: Where does your sequel, Miraculous Accident Part II, Nadir, bring us?

AG: Miraculous Accident did not feel complete without Nadir’s response to Edyta – which, in the second part, unfolds as a film he directs about her life after 1968: She forms a small cine-club in Haifa that no one comes to and where, all alone, she watches the films of her former Łódź students that once spoke of revolution, in an act that feels like an instance of necromancy.

The life of Jarek, the third figure in the triangle, occupies a major chunk of the plot, in a way that sadly mirrors the reality we’re living through now; after all those decades in which we believed we were preparing ourselves – learning and unlearning the mechanisms of history, crafting our oh-so-critical language – we now realize, not through studying or reflecting on the past, but by living this present, how people in history so often became apathetic to the suffering of others, how they surrendered to the illogic of national indoctrination, and how easily they were willing to bend their values and resort to open violence for the so-called good of the nation. I think that’s where it brings us.

Stills from Miraculous Accident Part II, Nadir, 2025

___

Miraculous Accident was commissioned by steirischer herbst ’24 and co-produced by Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin. Its cinema version premiered at Berlinale 2025, its exhibition version at “Familiar Strangers. The Eastern Europeans from a Polish Perspective,” Bozar, Brussels, in 2025, curated by Joanna Warsza. The second part, Miraculous Accident Part II, Nadir, was commissioned for the Kyiv Biennial 2025 – “Near East, Far West” and co-produced by TAXISPALAIS Kunsthalle Tirol and is presented together with the first part, Edyta, as a double video installation at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw.

The artistic research was commissioned by Berlin Artistic Research Programme. The entire project is produced by CaSk Films.

ASSAF GRUBER (Jerusalem, 1980) is an artist and filmmaker living and working in Berlin.