Leila Peacock: I recently heard a curator from a large institution describe the relationship between an artist and a curator as “somewhere between a stalker and a close temporary friend.” What are your thoughts on the dynamics of this relationship?

Fanny Hauser: [Laughs] That’s a very fitting description, somehow! Indeed, I guess we have all had to stalk artists at some point, usually when production shifts into high gear, to ask “Where are you?” or “Where’s the work?” After almost ten years co-running a project space, the Kunstverein Kevin Space in Vienna, I’m used to working very closely with artists, to helping to make things happen at every step of an exhibition, despite our very limited resources. It’s always a question of building up mutual trust – you become more like partners in crime, and when it happens, it’s probably the most beautiful part of being a curator.

LP: You studied Comparative Literature and Art History. Are the critical strategies required by the former relevant to curation?

FH: The focus of comparative literature usually lies on transcultural dialogues and the question of translation – not just literary translation, but also translation between different disciplines. I’m interested in thinking beyond the visual arts, or working with people across a variety of media. At the Ludwig Forum in Aachen, for instance, I curated a survey exhibition of the Yugoslav avant-garde artist Katalin Ladik, who conceives of all of her work – spanning collages, textile works, photography, video, sound, and performance – first and foremost as poetry.

I don’t really believe in “newness” or in prioritizing artists of a certain age, but am rather interested in how certain art-making raises questions pertinent to today.

LP: The late curator Koyo Kouoh, who spent her youth in Zurich in the 1990s, talked about the surface sheen of art tourism versus the folds and the cracks of Zurich and its history of art-activism, the latter being fertile ground for the avant-garde, especially in the 80s and 90s.

FH: Kunsthalle Zürich was founded precisely during that time, in 1985. I originally come from Vienna, and unlike the cultural scene there, which is so ingrained in the history and in the fabric of the city, Zurich’s creativity seems to have emerged from something different, including a broader awareness of its place among other cities.

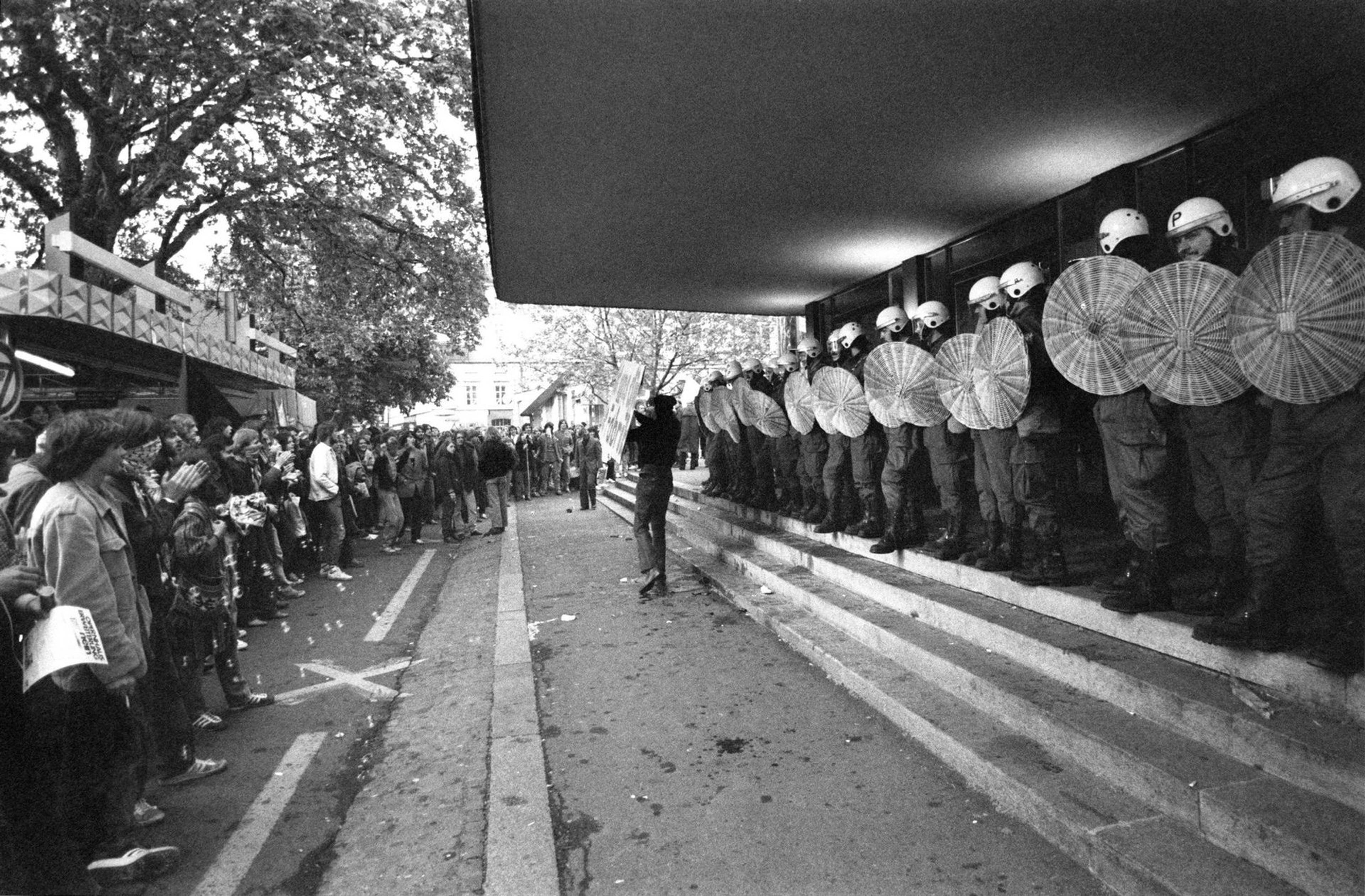

Organizations like the Shedhalle and Autonomes Jugendzentrum [Autonomous Youth Center] emerged from a very particular moment, when students reacted to a conservative turn in city funding in the so-called Opernhauskrawalle (Opera House riots). While the founding of the Kunsthalle was not directly linked to these protests, the spirit of upheaval certainly helped clarify the local need for such an institution, which had long existed in Basel and Bern [founded, respectively, in 1872 and 1918].

Demonstrators faces off with the police in front of the Zurich Opera House, 30 May 1980. Courtesy: the archive of the Neue Zürcher Zeitung

Pre-renovation interior of the Kunsthalle’s current location at Limmatstrasse 270

LP: Is there a specific exhibition that really moved you, or even changed your own approach to exhibition-making?

FH: Being part of documenta 14 in 2017, first as a team member and then a visitor, made me understand that art can also materialize through relationships that exist between people. Not all projects or gestures necessarily need to play out on a grand scale, and part of the value of art derives from how it operates within the social fabric. It shaped the way I look at art, certainly, but also my understanding of what an institution can be, as something that belongs to those who shape it through participation.

LP: I always think there is something very utopic about these huge exhibitions. They require everyone working on them to really believe in what they are doing, verging on a cultish devotion.

FH: What I found most striking about being part of such a huge and intricate endeavor – which unfolded across two cities, Athens and Kassel, including projects that echoed or conversed with one another – was that this collective undertaking produced something much bigger than the sum of its constitutive parts.

Erik Bulatov, exhibition invitation (recto & verso), Kunsthalle Zürich, 1988

LP: You’ve worked for big exhibitions and small museums, large art foundations and project spaces. What have you learned about the differences?

FH: From the beginning of Kunstverein Kevin Space, it was clear to me and my colleagues – Franziska Wildförster, Carolina Nöbauer, and Denise Sumi – that we would focus on supporting new productions and working closely with mainly international artists. There was a gap in Vienna at that time, which we and newer initiatives tried to fill. Due to our budget, the operations were very DIY, but we also all came from different institutional backgrounds and had this ambition to reach beyond the city itself.

These past three years, I worked at the Ludwig Forum. It was my first time working in a collecting public institution, where the structure is more layered and the dynamic involves long-term planning.

I was drawn to Kunsthalle Zürich because it can be something in between all of these institutional formats. As a non-collecting institution, it remains quite flexible. It has a history of presenting important survey exhibitions – Ian Wallace, Yang Fudong, and Nicole Eisenman come to mind – while retaining a certain hands-on feeling, and it gave artists like Wolfgang Tillmans, Jana Euler, and Christodoulos Panayiotou their first institutional exhibition. In the tradition of the Kunstverein, its structure is also member-based, and so retains a certain democratic idealism.

View of Nicole Eisenman, 2007

View of Ian Wallace, “A Literature of Images,” 2008

View of Yang Fudong, “Estranged Paradise. Works 1993 – 2013,” 2013

View of Jana Euler, “Where The Energy Comes From,” 2014. All photos: Stefan Altenburger Photography

LP: Philosopher Suhail Malik has criticized the category of contemporary art for the ways it can seem “condemned to newness.” How do you feel about this term?

FH: It might be more productive to approach this term etymologically, its literal translation from Latin being “with the time.” I don’t really believe in “newness” or in prioritizing artists of a certain age, but am rather interested in how certain art-making raises questions pertinent to today, regardless of when they originated. In September, we will open the first institutional solo show of Rose Lowder, who has been making experimental, analog films with a strong interest in ecology since the late 1970s. How can you describe someone who has been working so long as contemporary? She still shoots with a 16mm Bolex and constructs the works entirely “in the camera,” frame by frame, as they pass the lens. She films exclusively in nature – landscapes, flora and fauna and ecological sites – and also leaves some frames empty, which she keeps track of with elaborate visual transcripts and later fills. She even has one series of reels made entirely of leftover film, which she calls “Bouquets.”

LP: Perhaps that’s a nice framing metaphor for a curatorial program, a bouquet.

FH: Actually, her practice has been quite important for me in how to think about my own work, especially this idea of building a work “in-camera” – bringing together all those different stories, generations, and geographies into a program for the Kunsthalle.

View of Klara Lidén, “Over out und above,” 2025. Photo: Cedric Mussano

LP: In a recent article for Spike, your predecessor at the Kunsthalle Zürich, Daniel Baumann, lamented that institutional curators nowadays are expected to appeal to everyone – local and international publics, donors, the avant garde, and so on – which has made them unworkably cautious and unhappy. Can you sympathize with this?

FH: I certainly can. I also think that each point in time and each institution presents a unique set of challenges. We not only confront and fulfill expectations; to an extent, we also shape them. Raising the bar in terms of what institutions are expected to deliver has gone hand in hand with the seemingly ceaseless artistic production at all levels, including academies, the market, and in its general reception. We should acknowledge their presence, but not be moved by them.

___

Klara Lidén

“Over out und above”

Kunsthalle Zürich

14 Jun – 7 Sep 2025