Ivana Bašić’s (*1986) figures string themselves to an innate desire for the otherworldly, the divine. Born of a need to break from the claustrophobia of embodied living, sculpting functions for the artist as a form of passage, from the realm of the material – wax, glass, bronze, steel & alabaster – into a boundless, ethereal plain. What emerges from months of working in the studio in a kind of fugue state, sometimes verging on psychosis, are figures at once unfathomably alien and eerily human – knots in spacetime that appear like angels, faceless and entrancing. During her exhibition at MO.CO. Panacée, Montpellier (previously at Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin), I spoke with the artist about the arduous process by which she gives form to these vulnerable yet formidable figures. Neither horror nor sci-fi, these sculptures are the fruits of a gruelling battle Bašić has fought with the human condition.

Left: I had seen the centuries, and the vast dry lands; I had reached the nothing and the nothing was living and moist, 2018–24; right: Exuviae, 2024. Installation view, “Metempsychosis,” MO.CO., Montepellier, 2025. Photo: Marc Domage

Nikolai von Moltke: Contrary to conventional representations of human insides as perverse or disgusting, your works feel vulnerable and inviting. When did you begin sculpting forms without skin?

Ivana Bašić: In the beginning, I was really interested in the material reality of this body we live in. Not the appearance of it, but its hyper-materiality. It’s what we ignore at all times, and it became, for me, absolutely necessary to look at. For my grad school thesis, I began researching how we dress ourselves into ideas of normalcy, constructed upon the politics of labor. What is an able body? What constitutes “wholeness?” There are all these invisible systems of control embedded within our culture, so that every time the matter starts to overpower the man, it is considered a weakness and looked down upon in society. Body odor, body fluids, wounds, cuts, any openings where matter becomes visible is rendered unacceptable. Hygiene is a practice where we go into sterile rooms and, in private, are supposed to clean the material filth off ourselves. And I saw these practices of control to be a refusal of the truth of our own materiality and all that entails. The skin is the part that we encounter the world with, and it is the layer we try to control the most. So, removing the skin was my way of looking at the truth of it all.

Calling it horror speaks to our incapacity to accept and integrate the truth of our own bodies and our existence, because it’s the reality of what we’re made out of.

NvM: What motivated that research, and how did it turn into art-making?

IB: Ever since I was a child, I didn’t really register my body as myself; I registered it as a space I inhabit – a limited space, a temporal space. And growing up through the collapse of Yugoslavia, which brought on so much instability and one of the bloodiest wars in recent history, made even more visible the fragility of life, our flesh and blood. For me, realizing so early on that we are forced to endure the fate of matter, even though we are not just matter – that this space I inhabit will disappear – created a lot of claustrophobia and despair, and which are some of the core feelings I’ve been carrying throughout my life.

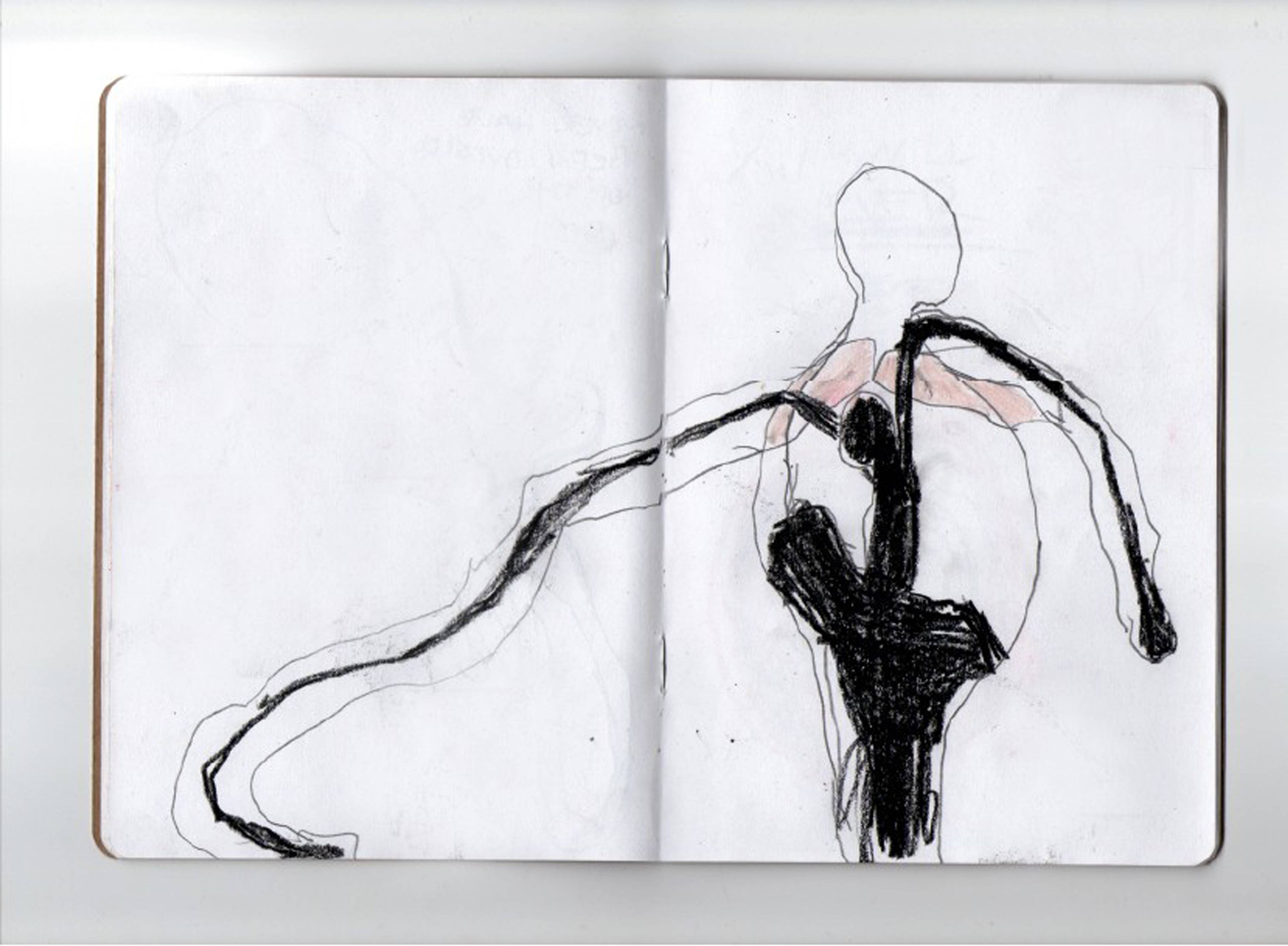

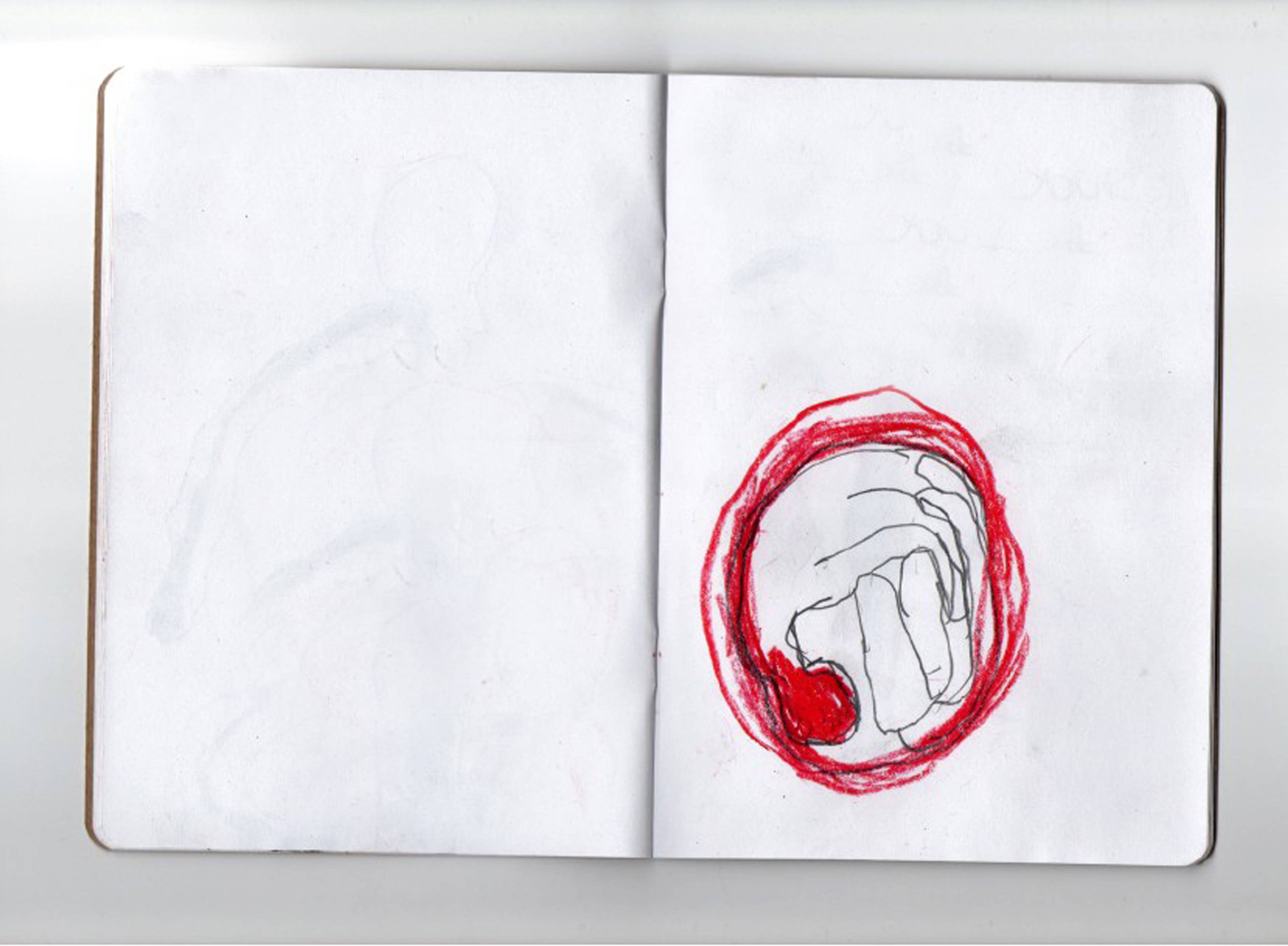

These two drawings are from around twenty years ago, before I even started “making art.” This was the impulse I had: to find the ways out of this body and this material world. This trauma of existence, if you will, was certainly amplified by the actual events in my life – the war, etc. – but it was not caused by them; it was within some of my first memories, literally since I was born.

NvM: There’s a recurring tension in your work between the violence of material limitations and the potential for transcendence. How does that shape your relationship to your sculptures?

IB: I definitely feel a lot of tenderness for them. But the sculpting process itself is a mystery: The only way for me to access the state in which I can make the work is to bypass the mind, and enter this other, unknown, limitless-feeling space. I take a lot of care in creating optimal conditions for this kind of meditative process to take place, blocking the outside world and listening to the same composition on repeat for months at the time.

I was making this one piece for “Metempsychosis” for fifteen months. It was clay, around my size – it’s not even that big. But I re-sculpted it literally fifty times – fifty different forms! For some reason, I just couldn’t finish any of them. It felt like all these half-formed fetuses that just did not want to be born. I felt like I lost my mind – like I was unplugged from the channel. It was terrifying, and I had a breakdown; I was in the studio for weeks, just crying, going through all of my existential hangups. And after I went through it and started working again, it took one-and-a-half days, and the piece was just there. It just slipped out of my hands, and with such an ease.

This is all just to explain how much of this process I don’t know beforehand; I dive into the void not knowing what I’m going to pull out. And when these beings, these entities, come through, they are so definitive and so finite that there is no ambiguity about any detail. Which is why I believe that they already exist on the other side. When I see them, I feel like I couldn’t have possibly made them; I just let them in. And I can suddenly feel like I’m not alone in the space anymore.

I too had thousands of blinking cilia, while my belly, new and made for the ground was being reborn | Position III (#3), 2020, wax, bronze, breath, blown glass, oil paint, stainless steel, pressure, 127 x 30.5 x 40.6 cm. Photo: Marc Domage

Blossoming Being #2, 2023–24, wax, white alabaster, breath, bronze, stainless steel, oil paint. Photo: Marc Domage

I sense that all of this is ancient and vast. I had touched the nothing, and nothing was living and moist. #4, 2022, white alabaster, wax, copper, pressure, grounding rods, stainless steel, petroleum jelly, 200.7 x 63.5 x 26.7 cm. Photo: Marc Domage

NvM: How does your idea of the Other figure into your work?

IB: The idea of the Other has been so analyzed and written about in philosophy. I was initially interested in the Abject, as the eruption of the Real into life itself, the experience of being confronted with one’s materiality and the horror that comes from it. Like witnessing ones own excrement or bodily fluids, or a corpse, all of which signify the anti-existence. Now, I think that the ultimate core of Otherness is this mystery of our own existence, of who we are or where we come from. Of the massive unknown at the nucleus of the being.

NvM: We often alienate our own bodies through the disgust we are taught to feel toward its interiority. It’s telling that body horror is hugely popular now! Art has responded by dissecting the body and our disgust toward it, shocking and seducing us with morbid transformations. And in that disgust we find desire.

IB: I think that calling it horror speaks to our incapacity to accept and integrate the truth of our own bodies and our existence, because it’s the reality of what we’re made out of. But I’m not interested in horror; it’s quite banal, actually. It takes a lot more to create the presence of otherness without making people repulsed. This is the space I try to occupy. One has to almost seduce the viewer – in order to have them consent to being pushed so far out as to examine their own existence and what they think they know.

So much of my process entailed pushing myself so far beyond my limits, beyond exhaustion, to the point of collapse. That’s where I could feel this other force taking over, literally carrying me.

NvM: Inasmuch as you feel as though you were simply a vessel in its becoming, how have you dealt with the attention your work has received?

IB: I’ve definitely struggled with it. I used to have this need to erase myself almost completely. So much of my process entailed pushing myself so far beyond my limits, beyond exhaustion, to the point of collapse. That’s where I could feel this other force taking over, literally carrying me. In those moments, it becomes so obviously undeniable that I’m not alone in this process, since this force is guiding me through it, cradling me – and the majesty of its presence becomes overwhelming. That’s the reason I keep coming back. So, I have learned to understand and acknowledge the fact that none of it would have been able to exist without me. That I am the one seeking this dialogue, this communion, and giving my life, every bit of energy, everything I have, to being able to carry whatever comes through.

NvM: I feel that no work of yours better expresses the simultaneous claustrophobia of the body and the dissolution of the self than The Temptation of Being (2023–24). At first glance, I saw a single limb, like the skinned leg of a large animal, but the closer I looked, the more it came unto itself, into itself. It’s as much on the brink of birth as the brink of death.

IB: Yes, totally! The first piece I ever sculpted [SOMA, 2016] was actually that exact form. It was materially different, but it was the exact same pose – a collapsed figure that has completely curled up into itself, almost inhabiting its own interiority – at the same time birthing itself and dissolving itself. That is sort of what the experience of life feels like to me – this process of synchronous dissolution and rebirth. This piece is the one that I keep coming back to, that exists outside of time and space for me – it’s like a self-contained system, or an imprint in my subconscious.

The Temptation of Being, 2024. Installation view, “Metempsychosis,” MO.CO., Montepellier, 2025. Photo: Marc Domage

SOMA, 2016, video, color, silent, 7:44 min. and wax sculpture, with weight, pressure, oil paint, rigidity, silicone, stainless steel, elastic bands, and ceiling mount. Photo: Ron Amstutz

NvM: I get a sense of optimism, maybe even hope. It no longer fears the reflection of itself in the ground, the reminder of its materiality. What changed for it to take on this renewed form?

IB: Over the years, I have learned to see that all the darkness is there and true, but that there’s also a lot of love and grace in the experience of being alive. Seeing so early on the brutality and limitations of this material world and coping with that is what my early works were about. So I feel like I went through it all and came out on the other side. Over the years my perspective has shifted, and now, I feel like I’m transitioning into formlessness, speculating on the ways in which the reduction or dissolution of the body is not a loss, but a moment of radical potential.

___

“Metempsychosis”

MO.CO. Panacée, Montpellier

15 Feb – 18 May 2025