Javier Peres (*1972) has always come for tomorrow. First in San Francisco’s Mission, then in Los Angeles’s Chinatown, the Cuban-born art dealer began in 2002 to exhibit queer artists and artists of color like videographer Berni Searle, filmmaker Bruce LaBruce, and photographer Dean Sameshima. In 2005, he decamped to Berlin and opened a giant showroom in a former industrial yard near Schlesisches Tor, where his roster of cheeky North Americans made an immediate splash. Packing openings of subversive works with raucous crowds, Peres’s first years in Europe yielded mixed mornings-after: an institutional career for enfant terrible Terence Koh; rampant speculation for works by Joe Bradley and Dan Colen; and, tragically, the death of Dash Snow, whose 2009 overdose prompted several peers in the gallery’s orbit to get sober.

The principal’s own stint in rehab and an eventual move into an august monument building on Karl-Marx-Allee seemed to temper his program, dovetailing with the 2010s’ upsurge of figuration to focus, as he recently told critic Éric Troncy, on artists “telling stories via painting.” Now an elder statesman nurturing the ambitious likes of Rebecca Ackroyd, Donna Huanca, and Shuang Li, Peres has of late opened exhibition spaces in his new home, Milan (around two corners from La Scala), and contemporary art’s buzziest market, Seoul (in the city’s historic center, Jongno-gu). Even as he tries to stay ahead of the identitarian turn in global art his own work presaged, he has stepped back from the gallery’s expanding operations to begin a new venture entirely: raising his first child.

Ana Finel Honigman: You moved to Milan recently, after spending what seemed like forever running your gallery from Berlin. That city is changing fast – what is your relationship to it nowadays?

Javier Peres: Many of the artists that we work with live in Berlin, and this really shapes the way the whole business functions. That’s where we handle exhibition production, administration, artist management and support, logistics … Rebecca Ackroyd’s fantastic installation at this year’s Venice Biennale and all the press and the writing around it were done in Berlin. Plus, we have the beautiful exhibition space on Karl-Marx-Allee.

View of Rebecca Ackroyd, “Mirror Stage,” Fondaco Marcello, Venice, 2024. Photo: Andrea Rossetti

AFH: I thought Berlin had changed entirely and become less of a hub of creativity. Nobody I know lives there full-time anymore.

JP: As of 2021, I’ve been based only in Milan, and for several years before that, I had already been steadily decreasing how much time I was in Berlin. Each team handles their own affairs more independently now, without requiring the regular presence of everyone in management on a day-to-day basis. With apps like FaceTime, I can see artworks as if I was there in front of them and give feedback, especially since these are artists whose work I already know very well.

AFH: But is Nick [Koenigsknecht, Peres’s gallery partner], there full time?

JP: Nick travels a great deal, so it varies a lot, but he is a key player in everything that happens in Berlin. For me, a new era started when I moved to the Zehlendorf area of West Berlin around 2018 or 2019, as my circle of friends changed a bit.

AFH: Yes. I remember.

JP: You know that we’ve been sober for a minute and that we have a different purpose in life, but Berlin is such an amazing city. One thing I have noticed, just from the administrative side of things, is that it’s become much more expensive, and the flexibility we once enjoyed is just no longer there. The €400 apartment doesn’t exist. Even the €800 apartment doesn’t exist, and staffing costs are through the roof. I think we are on the verge of another shift in the creative field in Berlin because it’s become so difficult to operate there.

View of Rafa Silvares, “Bloom,” Peres Projects, Berlin, 2024. Photo: Jerzy Goliszewski

AFH: When were you last in the city?

JP: I was there in December 2023 for a gallery dinner and to see Donna Huanca. I stayed at Soho House, and it was a trip – I didn’t recognize anybody, and nobody recognized me. I’m really out of the scene. But the gallery, interestingly, our openings are packed. There’s still a big audience in Berlin that consumes contemporary art – they just don’t buy it. That said, we’ve never been dependent on a local audience of clients. The German collector community never really clicked with what we were doing, even at a time when we did a lot of incredible institutional exhibitions. For us, Berlin was always our base for exhibitions and administration, and our international sales team worked with clients all over.

From the start in San Francisco, then in LA, it was important for us to be able to do exhibitions wherever we wanted. We’ve been doing shows in Berlin for a very long time, but that was more accidental than planned, and as our lives change, I think our locations will, too. My husband is Greek, our son will be raised in Italy, perhaps also in Spain and Greece, and I could see any of these places becoming new hubs if that makes more sense strategically and business-wise.

Some artists make some incredible works, then run out of steam. But there’s a place for that in the art world.

AFH: Does Berlin still have cultural cachet? Is there an allure to it that people recognize, or is it like Brooklyn now?

JP: Many artists love working there. It’s ideal for them because, among other things, there are no social commitments. Here in Milan, when I walk the dogs, I have to wear clothes and look presentable, and if I don’t regularly go to openings, somebody is going to call and say, oh my god, where were you? In Berlin, no one really takes that sort of thing into stock. You’re left alone to be self-centered, to put your work above your own sanity when you have a crazy deadline and need to go into overdrive, into beast mode.

AFH: There’s something about the climate. In the winter, it’s this perpetual same hour, the cold motivates you to hustle, and it has this kind of ennui that lets you lock yourself inside.

JP: I know what you mean! It can really support productivity. Berlin was my base for seventeen years, and I think a lot of good things came out of that for me.

AFH: You were the mayor.

JP: Well, I don’t know about that, but seventeen years is not nothing. It’s more time than a lot of people who have galleries there now have spent there, and certainly longer than my initial five-year plan for an exhibition space. When I moved to Milan, some people initially asked if was closing the gallery in Berlin. And I said, as long as Berlin will have me, I have no intention of leaving. Now, if you all get too crazy, if the Alternative für Deutschland [Alternative for Germany, a right-wing political party] starts running things, then I may not be able to stick around, but that’s not on me. So, as long as things remain kosher, we’re good, and we’ll keep adding to the cultural life of Berlin as best we can. That was always part of my intention, even if I initially also went there for selfish reasons – as is well documented, I had an affinity for the German type back in the day, and in Berlin, there was an abundance. But that’s all in the past now.

Javier Peres with Nicholas Grafia, Seeing Through Their Mouths More Than Ours (Cleaning Out the Closet), 2023, acrylic on canvas, 216 x 483 cm. Photo: t-space studio

AFH: I do a lot of my work via apps, but I don’t connect via the screen, and my ideas of creativity, of community, require physically being together in a place. How do you think these things work, now that you do so much remotely?

JP: What culture brings to the table is it picks out the people who are special and puts them together and pushes them forward. Fundamentally, at the end of the day, that’s what our job is, which, I feel, we’ve tried to develop a new way of doing. Don’t get me wrong: The way we do it is really crazy, because, unlike a lot of other galleries, we’ve always focused on discovery. Our program is a mirror – to the times, to society, to what we find interesting at any given moment. That doesn’t mean that it will be interesting tomorrow – some artists make some incredible works, then run out of steam. But there’s a place for that in the art world. If your star shines real bright for five minutes, that’s five more minutes than 99.9% of the people on the planet, and we don’t think that should be overlooked, either. Art history can’t only be about artists who had sixty years of making incredible, earth-smashing works. Besides, there are many factors involved in determining whether an artist makes it in the long run, not all of which have to do with their talent and abilities.

AFH: A lot of those one-hit wonders wind up defining their era.

JP: Totally. There are galleries that specialize in saying that such-and-such artist is like the canon. But we have developed a lane on the highway of culture that focuses on something else – we sift through and bring people forward when we think they have potential and an interesting point of view we should pay attention to. Whether they realize that potential is entirely up to them and to the universe.

AFH: You really hit on a lot of the seminal subject matter that has become global discourse, topics related to identity, wrapped up in fun and sexuality and irreverence. What are some of the central subjects in your roster now?

JP: When I started the gallery in 2002, the first artist I showed was Berni Searle, who is a mixed-race, South African lesbian. Second was a video artist from New York named Susan Black. Berni wound up in the Venice Biennale, Susan in the Whitney Biennial. We then showed Bruce La Bruce, then [the collective] assume vivid astro focus. From the get-go, I’ve been interested in shining a light on what I think is interesting, which has sort of become the checklist of a lot of galleries – showing Black artists, queer artists, artists from the Global South, etc.

View of Aks Misyuta, “Best Before,” Peres Projects, Seoul, 2024. Photo: Yangian

AFH: That was an era of rejecting how didactic the Whitney Biennial had become, and there was this need for glamor and joy and raw sexiness. But then you had someone like Terence Koh, who embedded this whole complicated conversation about ethnicity, assimilation, sexual orientation, and gender identification in this gorgeous, yummy package. Now, all that subtext has become really serious.

JP: I think we’re free-floating right now, to be honest, because the world has become huge, artistically speaking. I just came back from the Venice Biennale, which had a Brazilian curator for the first time. Most people have never heard of ninety percent of the artists in the main exhibition – they’re not only from the Global South (where I am from, too), but are Amazonian artists, Aboriginal artists, Native artists, First Nations artists. As an art dealer, I’ve been interested in artists from all over the world, regardless if they’re from the main art centers. Whether I agree with their perspective or not, I don’t care – I’ve never wanted to only show people who I agree with or who share my life experience. I’m interested in learning and feeling new things when it comes to art, and artists that can give us an insight into a new dimension have always fascinated me. That’s Rebecca, Donna, Shuang Li, Ad Minoliti, Rafa Silvares, Paolo Salvador …

AFH: Where does Dorothy Iannone fit into all this?

JP: Dorothy fits because Dorothy is timeless – she’s the season every season. She sadly passed away last year, but her work is still a real inspiration to a lot of artists that we work with. She’s the figurehead of a critical, overarching component that we look for, which is a truly authentic spirit. That’s never changed with us. Dan Colen had that. Dash Snow had that. Terence Koh had that. Matt Green, assume vivid astro focus, Amie Dicke, Eddy Martinez, Bruce LaBruce, David Ostrowski, Alex Israel, Jim Drain, Anna Sew Hoy – they all had that. The end result is different now, but what motivates the artists in our program today is very, very consistent.

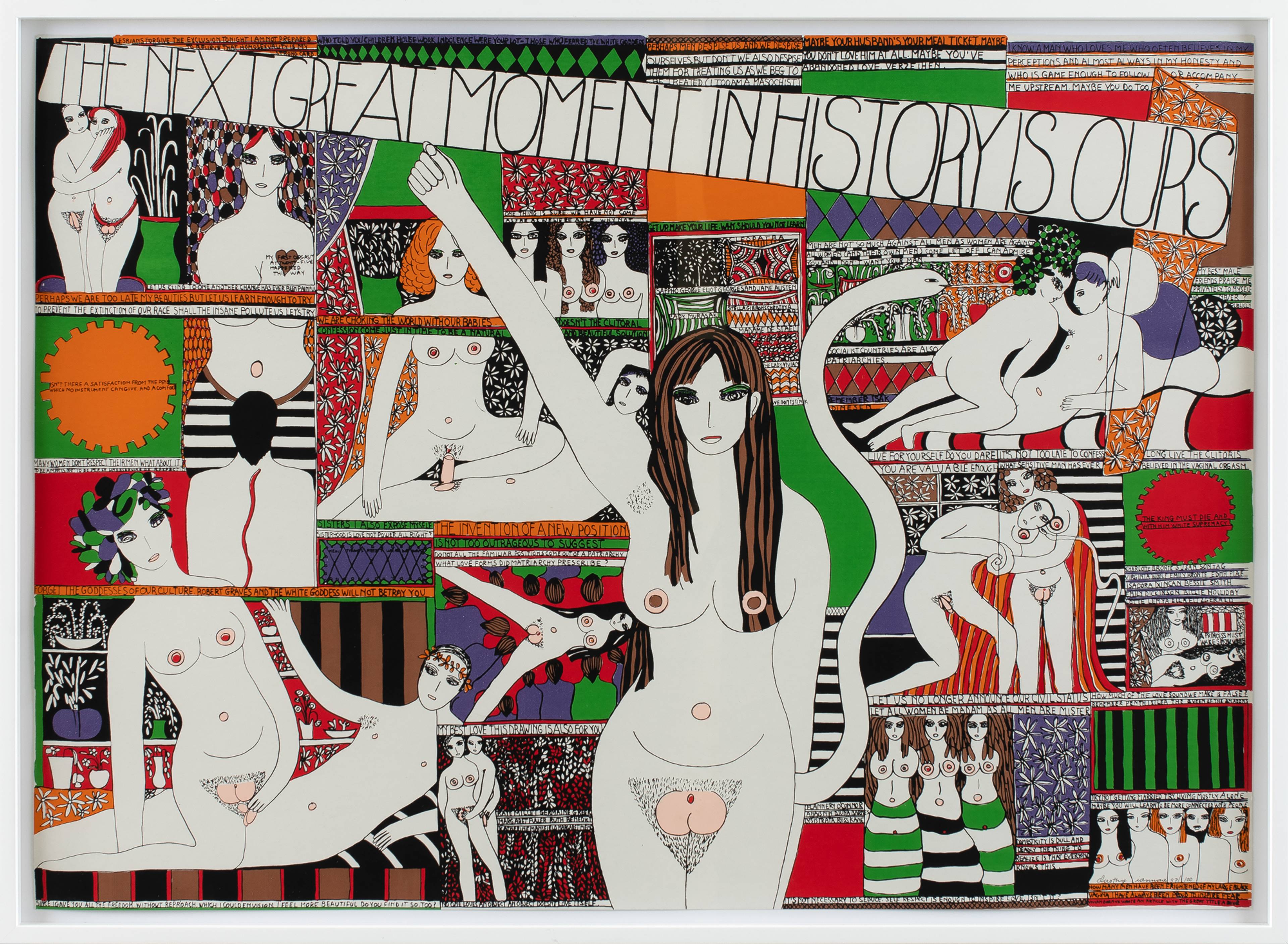

Dorothy Iannone, The Next Great Moment In History Is Ours, 1970, color silkscreen on paper, 73 x 112 cm

AFH: What does it mean to you to have done this one thing for so long?

JP: I’ve been involved in the art world for twenty-two years now. I don’t know how that happened: I think that many of the galleries my contemporaries started don’t exist anymore. Either they closed, or their founders died, joined other galleries, the museum world, auctions, etc. It’s wild that we’ve been able to keep open this line of questioning, this line of exhibition-making, through so many fundamental shifts. It can and needs to change further, though, to weather the various storms that are always brewing around contemporary art.

I’ve also really changed: For a long time, and I sacrificed myself for the gallery, but that’s not something I’m interested in anymore. I’m not going to die on the sword, as they say. My plan is to keep being involved with contemporary art, to focus on discovering and supporting artists, especially at critical stages, and to bringing works of arts into the hands of the people that value them, however that changes does over time.

AFH: I don’t like the idea of maturing or evolving, because there’s something very valuable about earlier facets and iterations of ourselves. You can remain consistently yourself, just manifested in different ways throughout a lifetime.

JP: Totally. There’s an amazing painter we work with, Daniele Toneatti, who was born in 1989 into a very artistic family in Veneto and is super-informed about art history. When we did his first solo exhibition in the Milan gallery earlier this year, so many people who came asked, is this a group exhibition? And we said, no, it’s a solo, it just looks like twenty different artists. When Gerhard Richter or Picasso were changing from style to style, it happened over the course of years, when the world moved at a different pace. Now, it’s all coming together – Daniele comes from and was raised in this world where information flows, where he has access to and an ease with information that we didn’t have, which he manifests in his painting. That’s the part that remains magic to me, and why it’s all about these objects. Because the one thing that remains when you and I are both long gone are these works of art, these paintings and the ideas they represent.

View of Daniele Toneatti, “Brand New Love,” Peres Projects, Milan, 2024

___

Anton Munar

“Malas Hierbas”

Peres Projects, Seoul

4 Sep – 27 Oct 2024

Brent Wadden

“ASLSP”

Peres Projects, Berlin

13 Sep – 16 Nov 2024

Cece Phillips

“Conversations Between Two”

Peres Projects, Milan

26 Sep – 15 Nov 2024