In her new book, Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art (2023), Lauren Elkin takes up the idea of the woman artist whose work reflects the experiences and insights of her own body. Drawing on case studies from 20th- and 21st-century feminist art histories, Elkin considers artists whose ways of working and, by extension, being in the world convey the fraught nature of embodiment. By design, Art Monsters is not universally laudatory, interweaving art history with piquant criticism of work by the likes of Kara Walker, Carolee Schneemann, Betye Saar, and Dana Schutz. We spoke with her last month about the stakes of feminist art monstrosity.

Esmé Hogeveen: To begin with, how would you define an “art monster?”

Lauren Elkin: The phrase comes from Jenny Offill’s 2014 novel Dept. of Speculation. Offill is describing a protagonist whose experiences of becoming a wife and a new mother threaten to overwhelm her sense of self. This happens semi-inadvertently. Offill writes that the character doesn’t set out to become a wife and mother; rather, she was going to be an art monster, the kind of person who doesn’t concern themselves with the details of everyday life and lives only for their art – selfish, egotistic, and, importantly, most often male. After appearing in Dept. of Speculation, “art monster” became part of the feminist lexicon, specifically popping up in first-person essays written by young women wondering if they could simultaneously be writers and mothers. That aspect was important to me, but the phrase resonated long before I became or even thought about becoming a mother.

I started writing about the art monster as a way of challenging the societal boundaries and self-policing women learn from such a young age. In her 1931 essay “Professions for Women,” Virginia Woolf describes how the angel in the house – a kind of Victorian anti-art monster –sought to prevent her from writing about what she wanted and in the way she wanted to. Woolf said the real challenge wasn’t killing off the angel, but “telling the truth of my own experiences as a body.” It seemed to me that if the art monster was the antithesis of the angel, part of that monstrosity had to do with making work that tried to be honest about the body and what it feels like to live in one, specifically a female one, whether by birth or by choice.

Lauren Elkin, Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art, 2023. Courtesy: Penguin Random House

EH: Art Monsters focuses quite closely on second-wave feminist artists. Why?

LE: I think it partly reflects the circumstances of how the book came together. As a writer, I tend to do a little too much research. I love to be in libraries and around books and papers, and I ended up doing a deep dive into Carolee Schneemann, Hannah Wilke, and other artists from that period. I had intended to include a balance of artists from the 1930s down through today, and to focus more on the female surrealists, for instance, but it increasingly felt like I had so much to say about the artists of the 70s. The birth control pill and abortion had just been legalized in the US, and it’s such a unique moment in history in terms of how women were thinking about and understanding their bodies.

I also knew that I wanted to write about Woolf and Three Guineas [1938], and I had this epiphany that the most relevant part wasn’t Woolf’s idea of the angel in the house, but of telling the truth of our experiences as bodies and of the woman writer as a fisherwoman. There are things she wasn’t allowed to say about the body because it would be too shocking, but she thought things might be different in fifty years. It made sense to think of Woolf looking forward half a century and to place her in a context with Carolee Schneemann and Kathy Acker and other women artists doing things that women couldn’t do in Woolf’s day.

I’d sworn not to make a hagiography of badass women. Instead, I wanted to be writing into a problem and exploring possible responses to it.

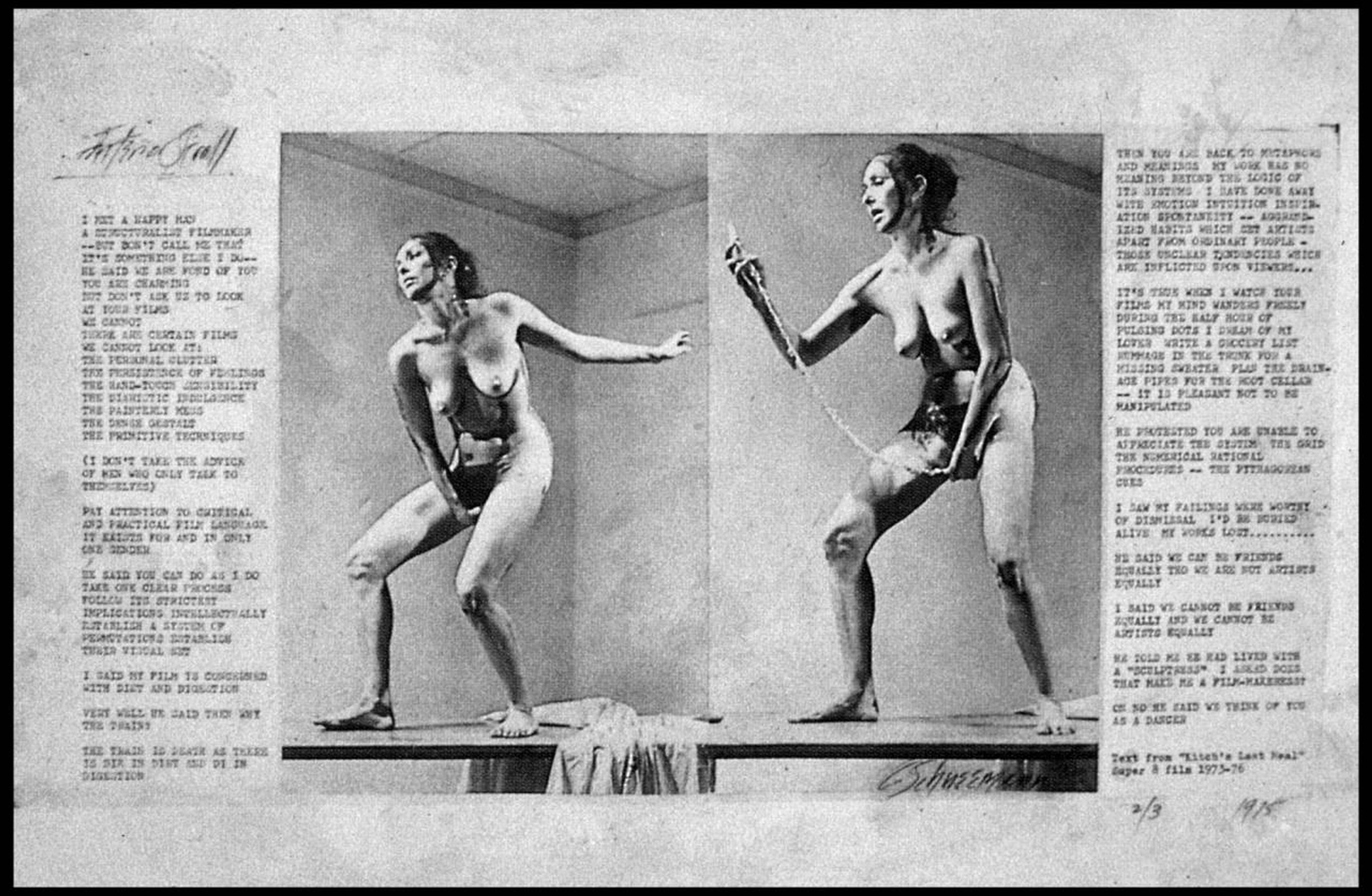

EH: Speaking of Schneemann: Was she always going to be integral to your project of defining an “art monster?”

LE: I always knew that I wanted to include her, because I thought Interior Scroll [1975] was a kind of urtext of feminist monstrosity – not vampires or zombies, but actual women doing freaky things with their bodies in their art. I saw her MoMA PS1 retrospective “Kinetic Paintings” in 2017 and I was excited to see some of the work she’d made with menstrual blood, such as Parts of a Body House Book [1972]. Initially, I had a chapter that I ended up cutting because it read like a list of art with period blood, which was potentially essentialist. I do claim the right to a strategic essentialism, as in women and people with uteruses have a right to talk about their bodies and the things we experience, but I also wanted to make sure the book was as inclusive as possible to trans women and trans men who menstruate. The chapter didn’t add up to something interesting, but the breadth of Schneemann’s work and the fact that she started as a painter, but very quickly began fucking with her painting – making it spin and burning it and pasting things onto the canvasses – it was clear she was impatient with painting and interested in venturing into other media. I became interested in her formation, in who she was as an artist, but also in how she attempted to work against that inheritance and to make painting jump off the canvas. She’s now one of my favorites.

Carolee Schneemann, Interior Scroll, 1975, beet juice, urine, and coffee on screenprint on paper. © Carolee Schneemann Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and DACS, London 2023

EH: Art Monsters includes some of your own art criticism, which I found refreshing, as theory can often prevaricate or defer to existing cultural reception. How did you approach integrating criticism into a study which, in many ways, is about refusing traditional logics or valuations?

LE: The chapter about Dana Schutz’s Open Casket [2016] grew out of my writing on Kara Walker and Betye Saar, and the task of defining a limit had been nagging at me. I’d been writing a chapter about Saar’s Extreme Times Call for Extreme Heroines [2017] and thinking about the heroine and the anti-heroine. I’d sworn not to make Art Monsters a hagiography of badass women. Instead, I wanted to be writing into a problem and exploring possible responses to it. Reframing women artists’ work compelled me to draw a line around what I meant by monstrosity, or else the book could turn into a big you-go-girl celebration. I didn’t want to be mindlessly celebrating – I wanted to be looking, really looking.

Betye Saar, Extreme Times Call for Extreme Heroines, 2017, mixed media and wood figure on vintage washboard, clock, 54.5 × 22 × 4 cm. Courtesy: the artist and the New York Historical Society

There were many times that I considered cutting the Schutz chapter, and I wondered whether the reception would be like, but I needed to explore the problem of the problem as a way of setting a limit and not suggesting that any risk-taking is inherently good. I thought it was important, not just from an art-historical standpoint, but from an ethical, feminist standpoint, to think about what it means to take risks. You can’t just sweep them under the rug and say, “Oh, well, art breeds empathy and can’t we all just settle down and be less upset.” The Schutz chapter also includes institutional critique of the Whitney, which had so few curators of color on their staff, and which blithely showed Open Casket without context or any reflections on the problems that it might raise, the hurt it might cause. There were so many issues germane to that painting and its reception that I couldn’t leave it out of a book that asks readers to think about art itself, how we look at art, and how critics and viewers mediate reception and influence the narratives around them.

We make biopics about Frida’s life and her love for Diego and her disfigurements and her horrible pain, and then put her face on kitchen towels and wallets and don’t think about her work.

EH: Thinking about the viewer-as-mediator reminds me of your essay on biopics for the summer 2023 issue of Spike, “How to Make the Woman Artist Exceptional.”

LE: I was originally going to title it “The Biopic Dynamic,” which is a reference to a quote from the filmmaker Céline Sciamma: “The biopic dynamic is politically not good.” In the essay, I argue against the marketing approach applied to artists like Frida Kahlo: We make biopics about her life and her love for Diego and her disfigurements and her horrible pain, and then put her face on kitchen towels and wallets and don’t think about her work. The biopic approach is a way of enjoying these women without acknowledging their radicality or having to deal with how uncomfortable the work might make us.

One of the key things that I hope people take from Art Monsters is that I’m less interested in the personal lives of women artists and more interested in their work. As much as we might want to, I don’t think you can really divorce the two; nevertheless, it seems that, outside of academia, most writing about creative women has a biographical focus. I’m not part of the New Critical school, where you can’t talk about anything but the work, but I do think that it often gets short shrift. So many of the artists that I wrote about took so many risks – including personal risks, like leaving their own children – to produce work, and I think it needs more direct attention.

EH: Lastly, I was intrigued by how you frame relations to embodiment from the 70s in response to the cybernetic age. Do you think we’ve become so dissociated from our bodies that we require entirely new techno-feminist frameworks?

LE: I’m very technologically wary, maybe even tech-phobic. I barely know how to use WhatsApp. I’m not into AI, and I hope it just crashes and burns. I want to live in the 20th century in Paris in an apartment with no smartphone. That said, I totally get the idea that the feminist art historian Christine Ross is working with, that the turn to abjection in performance might, in some ways, be the fleeing of disembodiment and the trajectory of disembodiment that technology tends to propel.

Genieve Figgis, Ladies in the forest (after Franz-Xavier Winterhalter), 2021, acrylic on canvas, 80 x 100 x 2 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Almine Rech

When I hear about things like writers suing ChatGPT or OpenAI for feeding their works into the beast, I do feel we have to draw some lines. But one thing that I’ll say in favor of technology is that while I was home during the pandemic, unable to go anywhere or see anything, I discovered the paintings of Genieve Figgis, who makes and posts some of the most wiggly, wobbly, amazingly embodied work. So I think there is probably a counterweight to this disembodied trajectory that we’re on, which doesn’t necessarily have to be about abjection, but can be about simply reminding us of the weirdness of our bodies.

___