In her upcoming memoir, Private I (ZE Books, 2025), Lynn Hershman Leeson (*1941) reflects on a life of art-making that relentlessly anticipated the world. From the constructed persona of Roberta Breitmore, who navigated life as a fabricated identity, and Lorna, confined by agoraphobia within her television screen, to the sentient program Agent Ruby and her recent ventures in microplastics – these works mark pressure points, foreshadowing the systems we would later grow into and possibilities still to be found within them.

In Private I, Hershman Leeson revisits five decades of boundary-crossing work, tracing how art, technology, and survival have remained inseparable in her life and practice. She describes art as both sustenance and disruption, a means of endurance that renders visible what would otherwise remain hidden. To speak with her is to enter the shifting terrain of authenticity, where the “real” is never fixed, but continually remade.

Andy DiLallo: Much of your work was decades ahead of its time, and only gained fuller recognition later in your career. Reflecting on your memoir, Private I, how do you make sense of the gap between when you made the work and when the world was ready to receive it?

Lynn Hershman Leeson: I try not to take it personally. I live in the Bay Area: Software’s in the air, you breathe it here; in other places, not so much. It generally takes people a long time to change and to understand what’s really going on in the present.

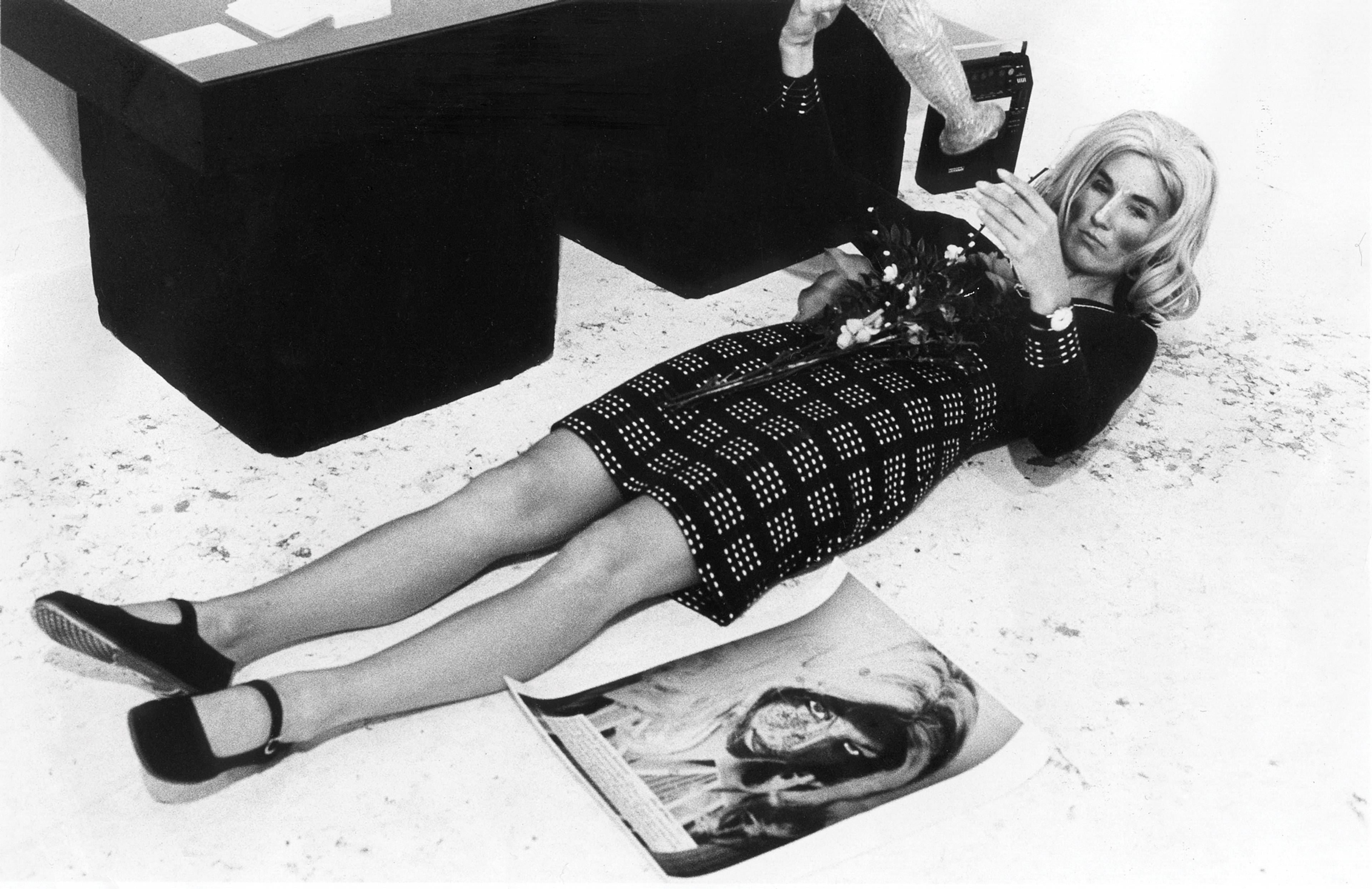

AD: One of your most well-known works is Roberta Breitmore [1973–], a long-term performance in which you lived as a fictional woman, with her own identity, bank account, and history. You’ve called it an “investigation into the precarious nature of identity.” What has inhabiting Roberta revealed about selfhood, and how do you see her legacy, now that online personas and influencers are everywhere?

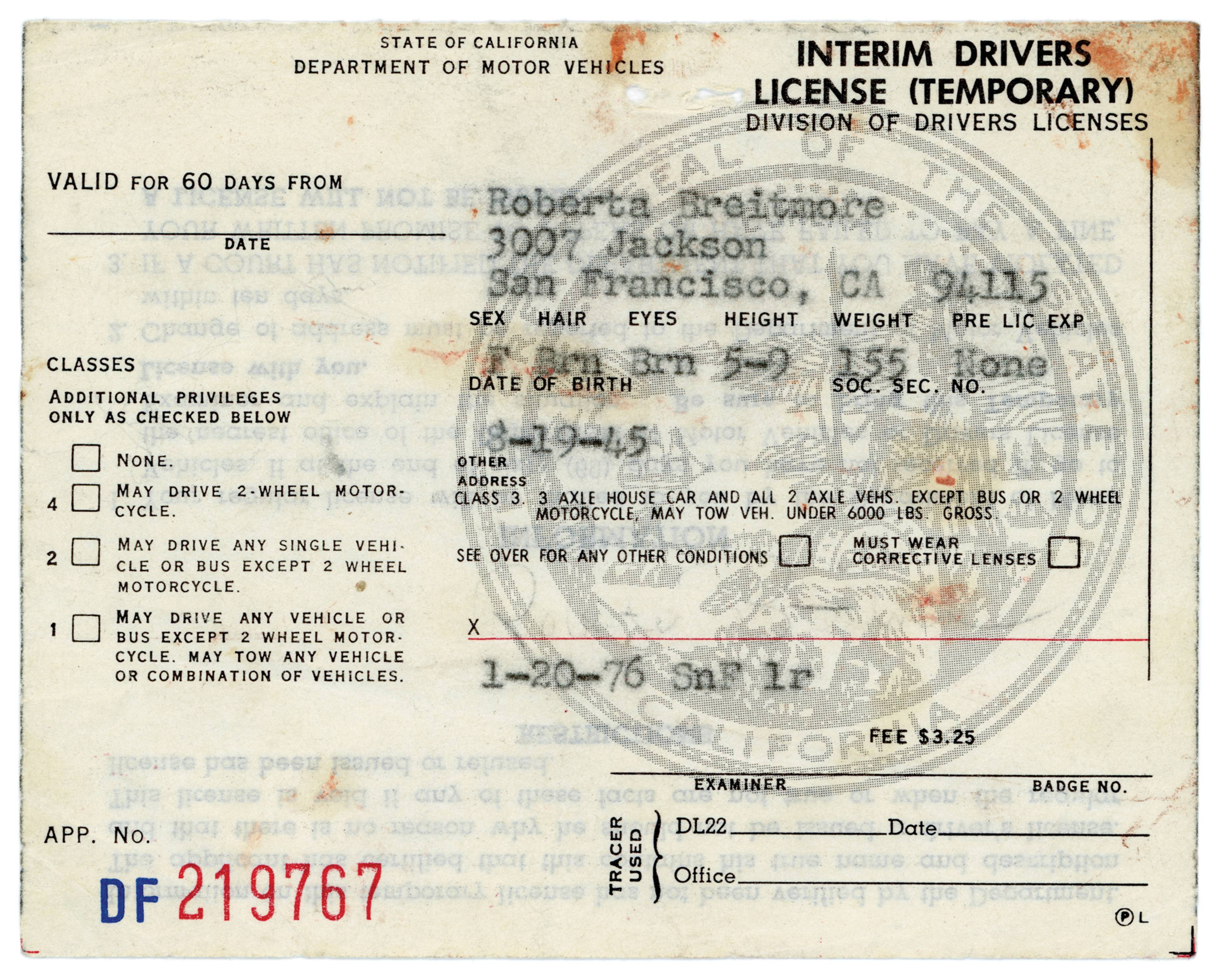

LHL: I started to question what reality was, and how a person is defined. Could you have a being with an identity where the person didn’t exist? I took one step after another – could someone who doesn’t exist get a driver’s license? A credit card? Personally, I couldn’t get credit cards, but she could. She placed ads, met people, and grew into quite a robust figure over the decade of her life – more than I, as a “real” person, was able to. That dichotomy, between my reality and what she could access as a fiction, always struck me – how she could move through systems that were closed to me.

AD: Was there something freeing for you in creating and performing Roberta as a fictional being?

LHL: For one, she had no credit problems.

Roberta in Red Coat (at Bus Stop), 1976

Roberta's Driver's License (DF219767, SnF 1r. January 20, 1976)

AD: It makes me think about a line from your 1994 essay “Romancing the Anti-Body: Lust and Longing in (Cyber)space,” where you wrote that “truth is precisely based on the inauthentic.”

LHL: It’s difficult to say what’s authentic and what isn’t. If you think of something, then it can’t be inauthentic, because you’ve created it. Truth, in that light, is not a hard reality, but a problem to define.

AD: In Private I, you describe the risks of performing Roberta – needing photographers for documentation and protection – while watching male artists’ outrageous behavior enhance their reputations in ways that remained off-limits to women. What did those experiences teach you about visibility and power?

LHL: I was overwhelmed by how much male artists could get away with – things a woman couldn’t even attempt. There were so many restrictions on womanhood, and all the more so on being a female artist. You had to stay “safe” according to how society defined it. I could never overturn a table the way Daniel Spoerri did and have it celebrated; I’d probably be locked up or never have my work shown again.

We have to be creative with what exists so it unfolds in a way that creates a better, broader perspective in which to live.

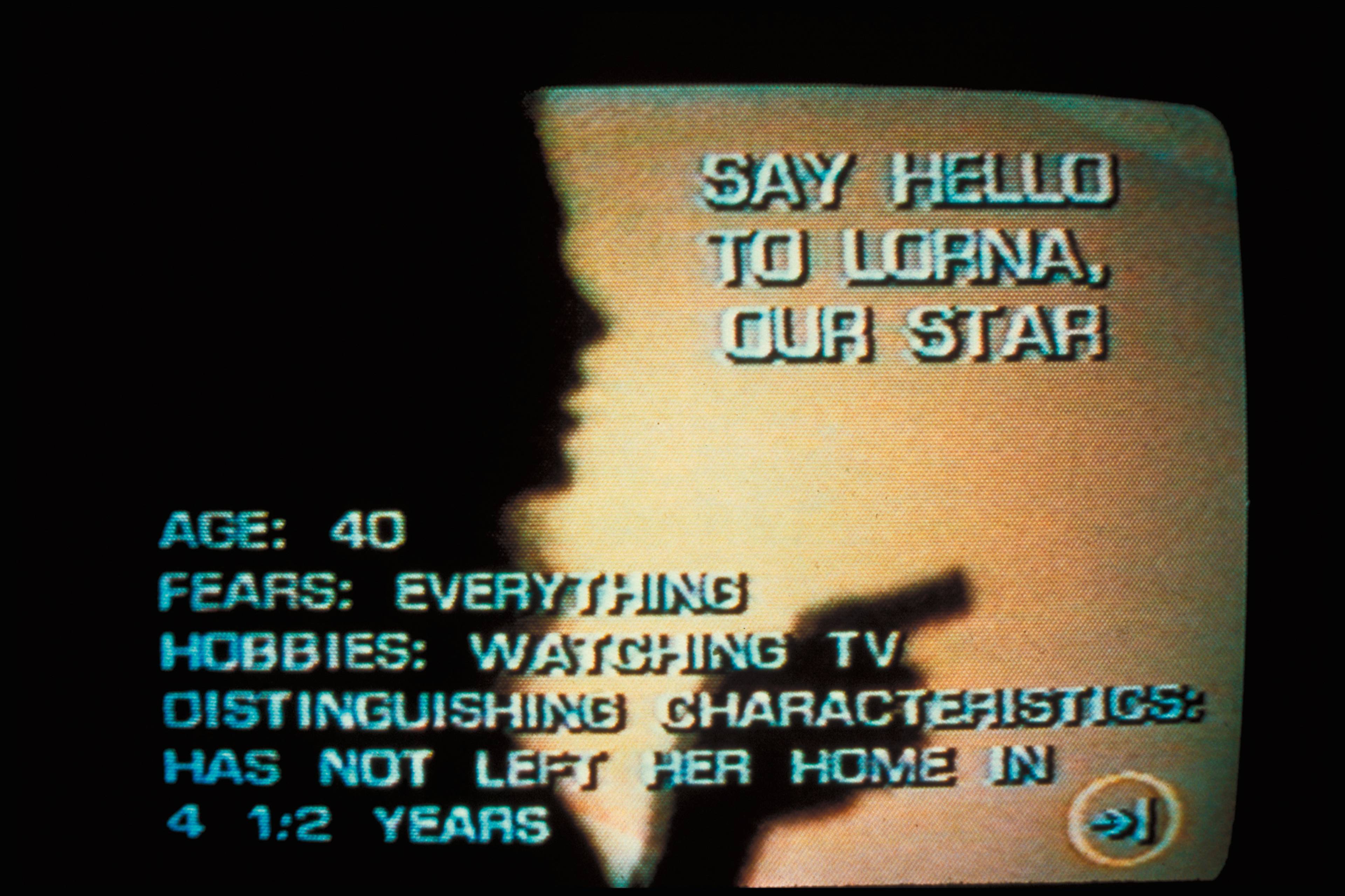

AD: Your work often shows people trapped in systems who search for autonomy through alternate identities. Lorna [1979–84], your interactive video installation about an agoraphobic woman, is a great example. In it, you capture the emotional toll of isolation – anxiety, paranoia, exhaustion – that comes from living under constant mediation. How do you see the role of art today, when so much of our experience is structured by digital platforms?

LHL: Artists sustain the human spirit – keeping alive our capacity for trust, imagination, and renewal. Art gives substance to life; it isn’t just what you need to do to survive. It’s another kind of survival: extending ourselves into the poetic.

AD: In your chat app Agent Ruby [1998–] and your film Teknolust [2002], you imagined artificial agents that could think, desire, and communicate. Seductively, unstably, both works channeled technology as at once a means of self-infection and its cure. How do you look back on them, now that similar agents circulate through everyday life?

LHL: Each era offers the language we speak in. When I made those works, digital culture was still forming its vocabulary – how to visualize networks, how to give machines a voice. That was the language possible then, and we reshaped it through invention. As technology evolves, so do our means of expression, and with today’s mass connectivity, the dialogue has become far more immediate – and far more difficult to escape.

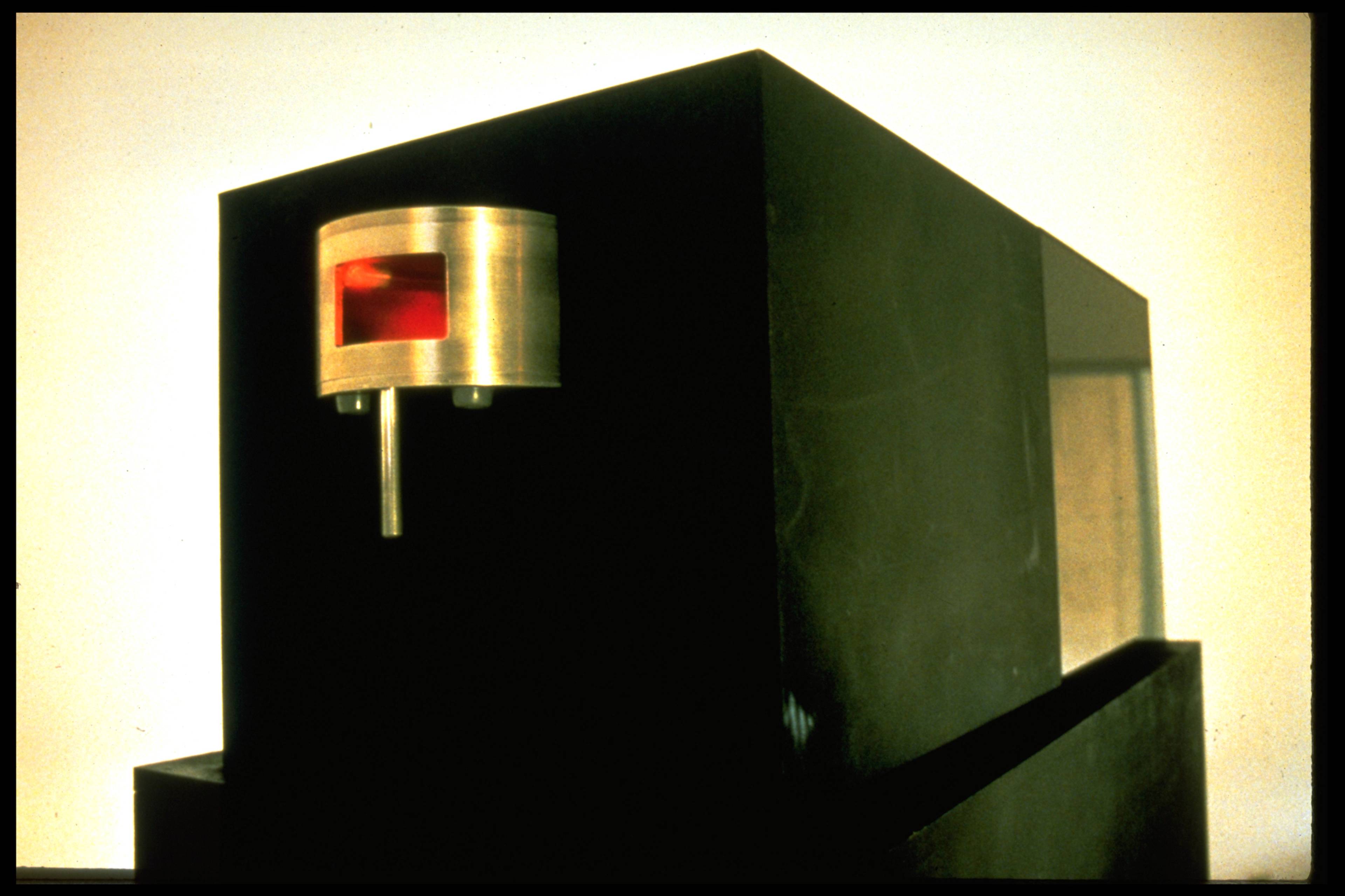

Lorna, 1979–84, interactive videodisk installation. Installation view, ZKM Karlsruhe, 2015. Photo: Tobias Wootton

Still from Lorna, 1979–84

AD: In Room of One’s Own [1993] and the “Dollie Clones” series [1995–96], you used cameras and mirrors so that the viewer’s gaze triggers feedback loops and self-reflection – the work watches you as much as you watch it. How do you see our relation to the gaze evolving now that surveillance is ubiquitous and images circulate until we are, in Hito Steyerl’s phrase, “represented to pieces” [“The Spam of the Earth,” 2012]?

LHL: There’s less participation on our part in communicating our images and what we say, because there are so many surveillance systems that we don’t even know about. They transpose who we are and sometimes falsely communicate a particular viewpoint of what that capture conveys about us. It isn’t cumulative or self-organized; it doesn’t build a whole person, just fragments that others assemble and use in ways we can’t control.

AD: Would you say we’re increasingly in a passive relationship with technology?

LHL: Generally, we are, because we assume we’re being captured somewhere and that we can’t control it – and even if we don’t see it, we assume some system is tracking us “for our safety,” while simultaneously making us unsafe.

[http://agentruby.sfmoma.org/]

AD: When you made those works, were you consciously pointing toward this future of pervasive surveillance, or was it more intuitive?

LHL: Intuitive, but also generative, in part because we had to grow into these systems. They became more viciously dynamic in how they captured us and what they did with the information.

AD: Your works don’t just depict these systems; they implicate the viewer within them.

LHL: In a way, they were warnings about the direction things were heading.

AD: If we’re past the “warning” stage, is it enough for art to remain poetic, or must it also confront the political realities of our time?

LHL: Yes. We have to convey where we are and, if possible, to suggest possibilities for change. Both are essential. Many people don’t realize what’s going on technologically with their identity or their property. These things have to be part of our dialogue for survival.

People fear what happens and want to leave traces of their existence. But whatever they try is different from what they are, so their ends might be better served trying to be artists.

AD: That makes me think of your project Twisted Gravity [2022], developed with the Wyss Institute at Harvard. The sculpture functions as a portable water-purification system, filtering microplastics and converting contaminated water into drinkable water. It’s an instance of art as direct intervention, changing not only perception, but material conditions.

LHL: I was lucky to find the right collaborator in scientist Thomas Huber, then at the Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research. If we can create works as examples of what the future could hold, rather than what already exists, it can give us hope.

AD: In Private I, a consistent thread is perseverance, whether in raising a child alone, living in poverty, making work in a male-dominated art world, and receiving recognition so belatedly. What gave you the resolve to keep going?

LHL: I couldn’t do anything else. This is what I did, who I was, what I believed in, whether or not it was recognized. If I didn’t keep striving for what I believed in, I would’ve been consumed by my expectations. I didn’t want that. I’d rather be unrecognized and still do what I believed in.

AD: What would you say to younger artists who find it materially difficult to pursue art today?

LHL: Examine your expectations. Concentrate on creating work and placing it in the world, even if it’s just to try to change what disappoints you. We have to keep that part of ourselves fresh, alive, and vital – which only happens when you don’t repress it.

Room of One’s Own, 1993

Interactive apparatus, interior view, miniature furnishing, screen, monitor

AD: In Private I, you write that what is essential is often invisible to the “I.” As you reflect on your life and work, what do you hope artists and audiences will learn to see more clearly, especially in our relationships with technology?

LHL: To be aware of the possibilities for human and global enhancement that we invent, but which we don’t necessarily use for that purpose. We have to be conscious of what can destroy the world as well as what could enhance it, and do all we can towards the latter by using the technology accessible to us.

AD: Things could always unfold differently …

LHL: Exactly. We have to be creative with what exists so it unfolds in a way that creates a better, broader perspective in which to live.

AD: Still, in today’s media environment, it’s easy to see why some people might feel nihilistic, as if they have no agency.

LHL: That’s why we need to create examples of what’s possible, rather than give up. It will guide our future. We don’t have to live with the restrictions technology imposes.

AD: What do you hope people take away from your memoir and your work?

LHL: I just want to encourage people to invent possibilities for their life and see what they are. It’s easier to be negative.

CybeRoberta, 1996, custom-made doll, clothing, glasses, webcam, surveillance camera, mirror, original programming, and telerobotic head-rotating system, 45.1 x 45.1 x 20.3 cm

AD: This is your first book; what was your process writing it?

LHL: At the beginning of the pandemic, I just started writing. I didn’t expect it to be a book. I was trying to hear myself – to see what I was thinking – which usually comes when I’m taping video or writing. It made me more aware of what’s going on and what I’m thinking about, and it created change.

AD: One last thing – what’s next for you?

LHL: I just wrapped up an exhibition about aging and its dynamics at the gallery Altman Siegel in San Francisco. I presume I’ll keep working on that – how and why we age, and why some species, like jellyfish, are “immortal.”

AD: It’s interesting to consider, alongside today’s technological quests for immortality – uploading the brain, biohacking, longevity. What do those say about how we face death?

LHL: People fear what happens and want to leave traces of their existence. But whatever they try is different from what they are, so their ends might be better served trying to be artists.

AD: I imagine it’s easier to face the end of a life if you’ve lived one fully.

LHL: Yes, and you have to understand the possibilities of living, of life’s dimensions, and to understand time: your time, and what you can accomplish. If you want to extend, put thought into provoking something universal that extends beyond you.

___

Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Private I: A Memoir is published by ZE Books.

Isabella Zamboni’s review of “Are Our Eyes Targets?,” Leeson’s 2024 exhibition at Julia Stoschek Foundation, Düsseldorf, is in Spike #80 – The State of the Arts.