Lisa Moravec: The story that you tell with your performance blends your biography with fiction. Among other things, you critically address your family’s involvement in Argentina’s military dictatorship, the pairing of sexual drive with your desire to make dance performances, and implied issues of corporeal (self-)fetishism and (self-)voyeurism. As you couldn’t dance in the piece when you made it, you chose another Marina to perform your role. Why did you make such an intimate, auto-fictional performance?

Marina Otero: This performance comes from a larger project, Remember to Live, in which I committed myself to making different versions, sketches, and works based on my own life until the day I die. It wasn’t a conscious decision to make such intimate pieces, but it has to do with my persistent obsession with dance from a very early age, while seeing how my life is transforming. The closest thing I could have and work with was my own body, my own life.

© Ale Carmona

LM: In the performance, you act as a narrator, not as a dancer. How did you become interested in verbal storytelling and self-filmed documentary footage as dramaturgical tools?

MO: I started working in a more narrative and verbal way with my first work, Andrea (2012). As a dancer, I had always found dialogues difficult, because up to that point, I had always used my body instead.

Writing an intimate diary was the beginning. I always carried it with me and wrote down everything I couldn’t say, and somehow, with psychoanalysis, I began to work with words and to name many things that were previously unnamed. Then, I started integrating these diaries into my dramaturgical practice and combining them with the language of dance, as well as with multimedia components, because I was also interested in video as a way to document the intimacies of life.

LM: Until recently, you have always made and performed in your own pieces. Besides considering your physical health, what performative possibilities have opened up with your shift from main character to storyteller?

MO: I went from being a soloist in Andrea and Remember 30 Years To Live 65 Minutes (2015) to sharing the stage with five actors in FUCK ME. The change, which obviously happened because of my health, has been a very positive one. Before, I had to make an extra-human effort with every work, as I was undertaking the whole creative process and performing the whole show on my own. From FUCK ME onwards, though, I became more aware of teamwork, which makes things more relaxed and loving. Now, I find companionship and things in the work process that weren’t possible before.

© Maca De Noia

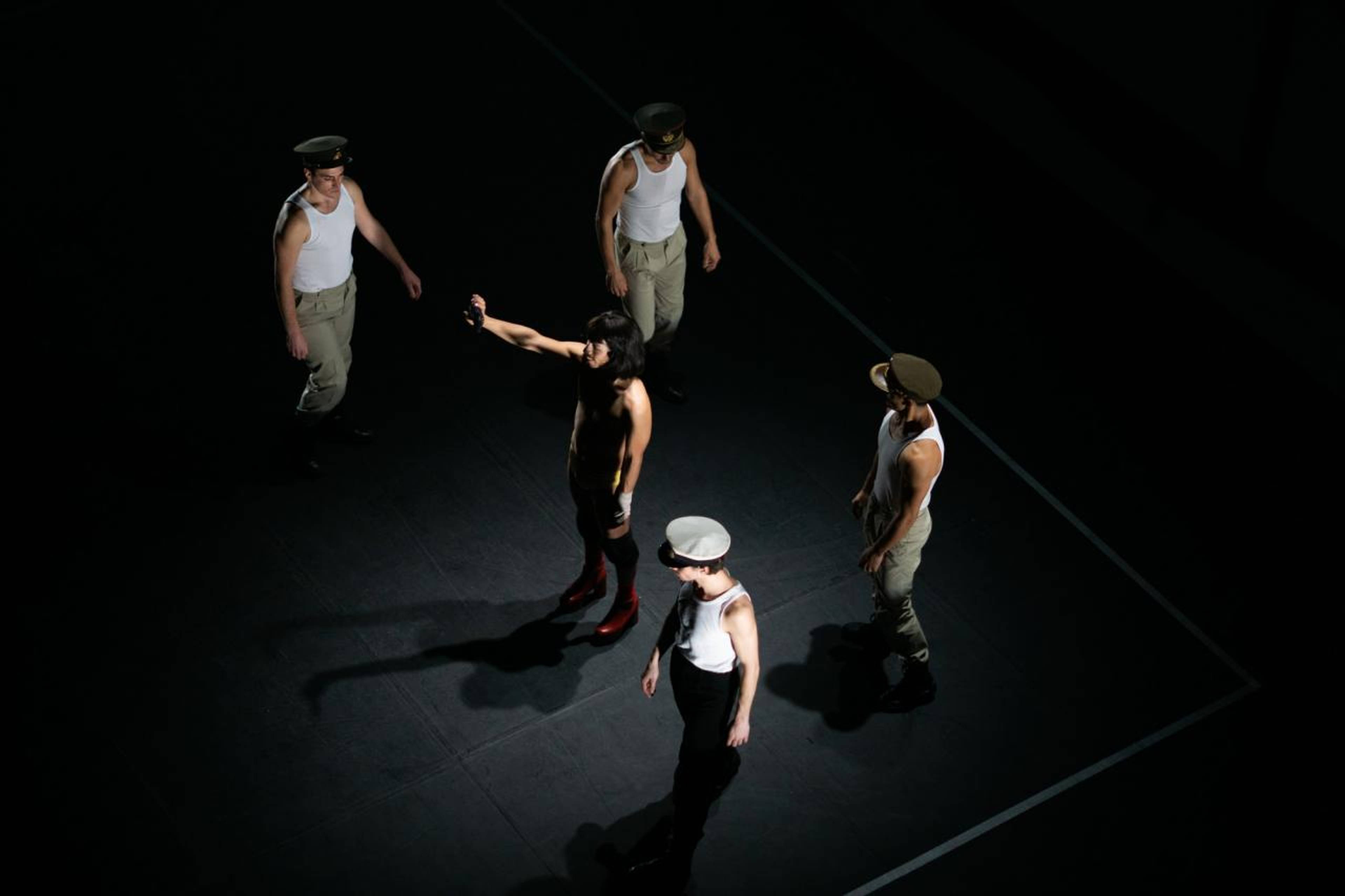

LM: In FUCK ME, you say that your health condition has kept you from having sex, which is why you turned to making a work about it. Why did you decide to use five male performers with the name Pablo?

MO: It's a form of revenge against the men who were somehow manipulating my life: As I tell in the play, at one point, I went out with three men named Pablo. The objectification of the female body, especially that of a dancer, was also very present for me.

LM: Amid an increasing visibility of queer bodies and aesthetics onstage, you are presenting well-trained, able, male bodies performing as members of the marine military, which accords with a more traditional ideal of masculinity. How does your approach to the representation of gender link to your feminist performance practice?

MO: It was important to me that they represent soldiers from the navy, as the piece relates to my family history and my military grandfather. My choice of performers had a lot to do with their being male, and perhaps they represent more the traditional image of the masculine body. But they appear both masculine and feminine in the way they move, and one of them also had to represent me as a woman.

I have always had an obsession for choreographing and fiction because I can’t stand real life.

LM: At ImPulsTanz, you are showing not only the group performance FUCK ME, but also a solo, LOVE ME (2022), that you made in collaboration with the playwright and theater director Martín Flores Cárdenas. How are the two works similar or different in terms of your working method and their movement aesthetics?

MO: Working on LOVE ME was very different from how I work alone as a director and a playwright – working on my own is much more sacrificial. With Martín, though, the collaborative process was very gentle. We met to eat, to think, and to write together, and when we separated, we shared the material and edited each other. The text, which took us one year to finish, makes up ninety percent of my solo dance.

I also incorporated that collaborative process physically, though it is a physicality that I had already developed for other plays. We called the language of movement a monster, as “a monster” appears in my previous plays. Since my back injury, I have not been able to move in the same way. The movements, therefore, had to be much smaller, which created a subtler body language.

LM: Which of these two performances challenges existing forms of intermedia dance performance more, and why?

MO: I would say LOVE ME, because it is a much denser play. It is kind of anti-entertainment, unlike FUCK ME, which has a very agile rhythm. The audience is always more resistant to LOVE ME, sometimes even angry, as it is difficult to watch.

© Maca De Noia

LM: In LOVE ME, you say that you are a “dancer who doesn’t dance.” What do you mean?

MO: It’s a bit of a joke. I am seated on the stage, while a text narrative is continuously projected onto the back wall. I don’t dance for almost the whole forty-five-minute piece; only at the end, I do so as a surprise.

LM: You are a self-trained dancer. When and why did you start dancing and developing a choreographic practice?

MO: I started dancing when I was very young. My mother attended dance classes from the time I was a baby, and she always took me with her, because she had no one to leave me with. At the age of three, I started going to expressive body classes, and later to classical, jazz, and Spanish dance. I became obsessed: As I tell in FUCK ME, at birthdays or family gatherings at my grandparents’ house, I always choreographed my cousins. I have always had an obsession for choreographing and fiction because I can’t stand real life.

© Maca De Noia

LM: How has your relation to dance and performance-making changed since your surgery?

MO: After the spinal operation, I began to approach rehearsals and creation differently. Now, I am a much more disciplined person, both with myself and with the interpreters – we practice yoga every day before performing, for example. The injury made me aware that I have to take care of the body, both my own and those of my colleagues.

LM: What are you currently working on? Another auto-fiction piece? Or just on dance?

MO: I am preparing a work called KILL ME, which is a continuation of FUCK ME and LOVE ME and also a part of Remember to Live, that will open in Madrid next June. It is a non-fiction piece, likewise with five performers – this time, four female and one male – that mixes dancing, singing, text, and audiovisual elements to play with the limits of fiction and reality. It’s a diary of my life documenting the last time it was disrupted by psychic illness, rather than by a physical accident.

___

FUCK ME

Akademietheater

25 July at 21h00 and 27 July at 19h00

LOVE ME

Schauspielhaus

28 July 2023 at 23h00