Dating to Punk Prayer, the 2012 protest-performance in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour that marked the coming-out of feminist collective Pussy Riot, Nadya Tolokonnikova (*1989) has cut an iconic figure merging art and activism. After serving jail time with Maria Alyokhina and Yekaterina Samutsevich on charges of “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred,” Tolokonnikova spent nearly a decade provoking Vladimir Putin’s regime with artistic actions inside Russia, before fleeing the country under the threatening designation “foreign agent” in 2021.

Now, OK Linz has organized the first exhibition of her work in a major art museum. “RAGE” darkly spans several rooms of OK Linz, centered around video of her protest-performances, but also including installations, prints, and, in the institution’s hall, a huge knife that hangs from the ceiling. Using calligraphy and orthodox icons, she inverts different traditions of aesthetic idioms to enact a feminist politics, the better to claim them as powerful tools. A documentary impulse prevails throughout the presentations of her earlier works – such as a replica of the cell where she served jail time – whereas more recent objects and prints testify to her development as a conceptual artist. Above all, though, her work rouses strong feelings – of anger, shock, and love – by communicating with all sorts of higher powers.

Patricia Grzonka: The exhibition actually starts outside, in the Christian chapel adjoining OK Linz on the square, with your installation called Pussy Riot Sex Dolls [2024]. How did you decide to use them?

Nadya Tolokonnikova: I am definitely sex-positive, but when it comes to sex dolls, I am worried about boundaries and the culture of consent. The problem I see with sex dolls is that they train a person who uses them to use women’s bodies as objects. With a real woman, you obviously have to ask for her permission, to care about her feelings, and make sure that she also enjoys the act. When I came across a sex doll for the first time in 2016, my initial intention was to put clothes on her and give her some dignity, which I did. I didn’t give them much thought after that, until I started thinking about sculpture, where I like to work with found objects. Sex dolls can only lay or maybe sit down, so I wanted to empower them in my sculpture by standing them up. We had to install this skeleton inside of each doll – that’s why they have these scarves on the backs of their legs.

Nadya Tolokonnikova, Sex Dolls, 2024. Installation view, Kapelle Unserer lieben Frau von Altötting, Linz, 2024

PG: You used a lot of religious symbols in “RAGE,” such as crosses, which wasn’t a context I expected for the work of a political activist.

NT: My dad is an artist, musician, and writer, and I think I really learned from him what an artist is. He would go to holy buildings: mosques, synagogues, Catholic and Orthodox cathedrals. The Orthodox church has a huge presence in Russia, of course, and I was always drawn to its aesthetics, the sounds and the smells, as well as its mystery and mythology. It is so rich, and I think it serves a very important purpose.

When I was in jail, I read the Bible for six months, as there was no other book the prison would give me, and I was thinking a lot about religion. I am not a religious person, and I look upon religion a bit more as an epistemological tool to analyze the patterns in society and psychology. I really think it helps people to believe in something bigger than themselves. And it really hurts me that the government in Russia, and conservative forces more generally, are always trying to capture religion and to use it against this liberational impulse.

I don’t mind everything that any organized religion has, but I’m going to mold it into something that suits me and people like me. I’m creating my own crosses, twisting the original form. This is my own personal religion, and it’s a feminist religion.

Nadya Tolokonnikova, Rage Chapel, 2024. Installation view, OK Linz, 2024

PG: Where is this liberatory impulse in Russia today? It’s so hard to get proper information about what is going on there.

NT: Well, there are hundreds of political prisoners there now, who have been suffering from the very beginning of the invasion of Ukraine. There are Russians devoting to and risking their lives for protest, but the price they pay is incredibly high. Most of the people who disagree with Putin’s regime disagree with the war. There is a pop artist called Monetochka who needed to get out of Russia because she had very strong anti-war words and became very political at the beginning of the full-scale invasion. She was already very well known, but she blew up recently when she released an album [Prayers. Jokes. Toasts., 2024] that talks quite openly about all these issues, and very critically of the regime. This album went to the top of the charts in Russia. When people have a safe option for showing their dissatisfaction with Putin’s political regime, they do so.

Art has to serve a purpose. It can be an analytical tool, in a way that a professor sits in her university office and writes papers.

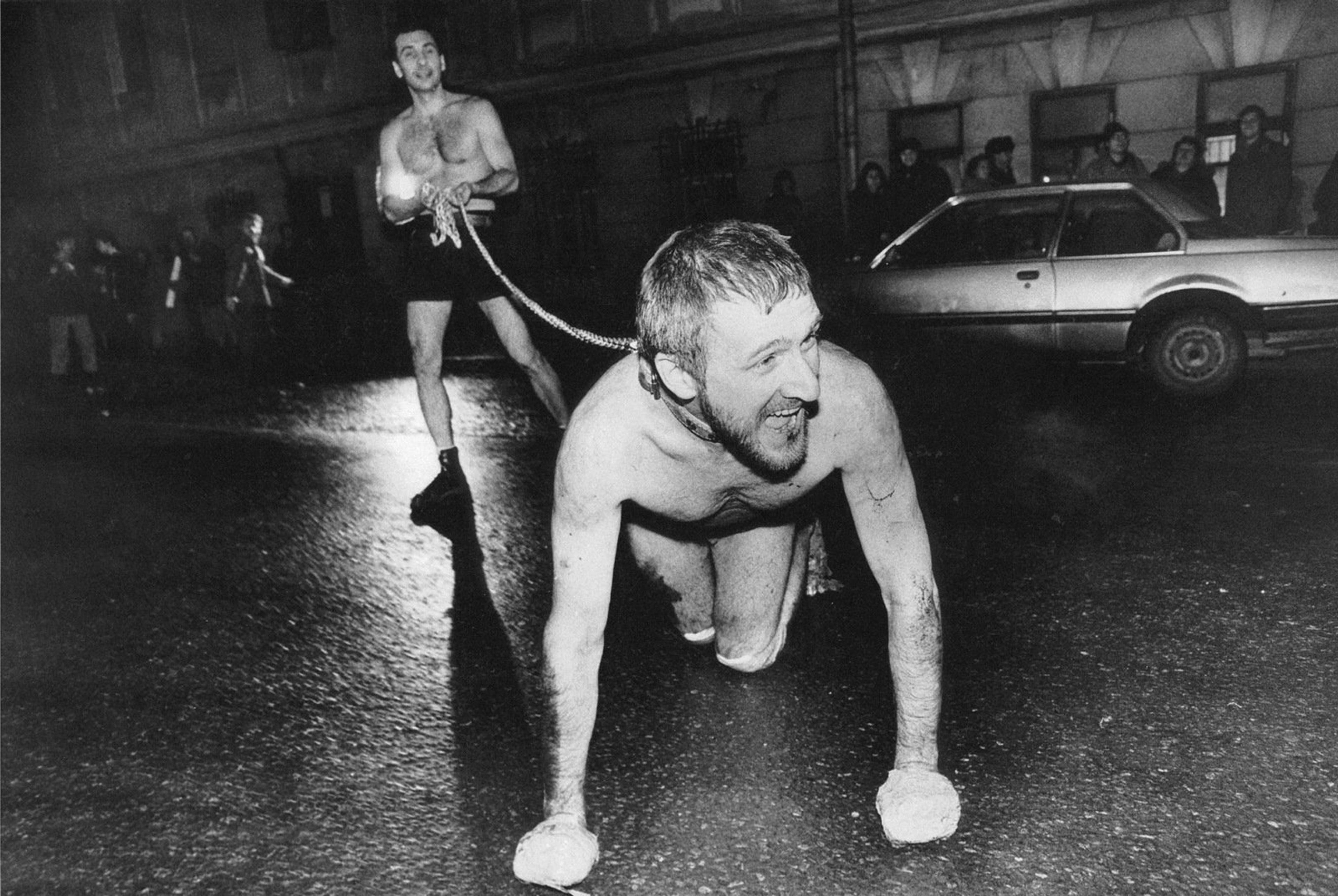

PG: A lot of Actionist art from Russian artists not only deals with violent topics, but is also explicitly violent in its expression. Years ago, in his dog performances, Oleg Kulik barked and bit in front of art galleries and institutions. More recently, Pyotr Pavlensky sewed his mouth closed in protest of your arrest, and also set fire to the ground floor windows of a branch of the Banque de France on Place de la Bastille in Paris; he was given a three-year prison sentence for this latter action. There is a degree of mutilation, destruction, and determination to go to the bitter end that I cannot imagine in a Western art tradition.

NT: Art has to serve a purpose. It can be an analytical tool, in a way that a professor sits in her university office and writes papers. Russians have experienced much violence. When Kulik started these man-dog performances, he really felt like it was a big breakthrough in showing the craziness, chaos, and freedom of the 1990s in Russia.

One of my videos in the Prison Room is called Organs, which I made in 2016, when the police started to search for me again and I had to escape Russia briefly. Friends sneaked me to Belarus, and from Belarus, I snuck to Kyiv. I couldn’t escape thoughts of self-harm. I really wanted to cut my veins – not to die, but just to replace this pain that I had, which, I guess, is how self-harm usually works. Basically, the way I use violence in art, I almost exclusively sublimate. I’m not a violent person, but this is the way for me to channel a trauma.

Oleg Kulik, Alexander Brener, Mad Dog (The Last Taboo Guarded by Alone Cerberus), 1994, silver gelatin print, 120 x 160 cm. Courtesy: the artists

Pyotr Pavlensky, Seam, 2012. Courtesy: the artist

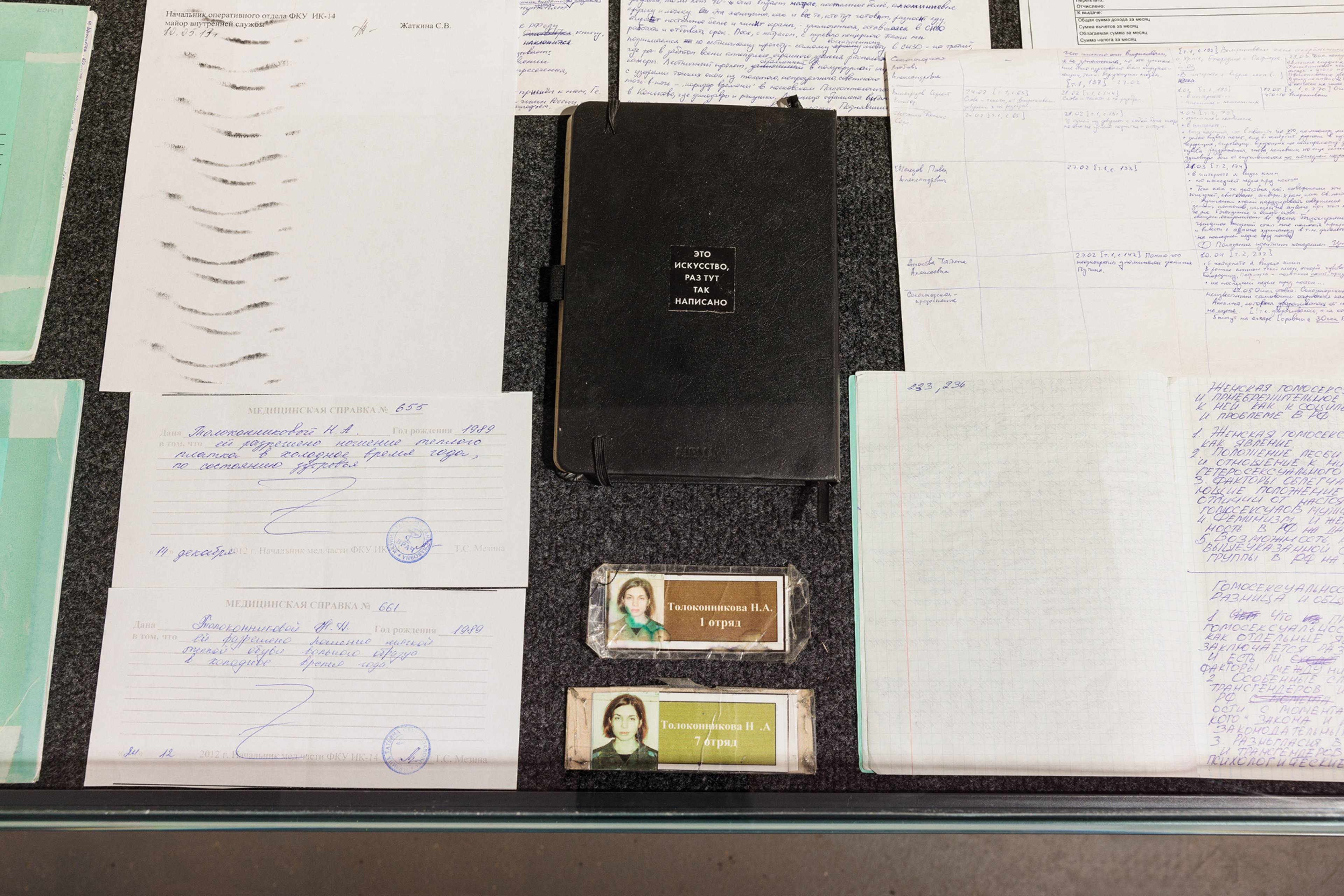

PG: The Prison Room is dedicated to your experience in prison. There is a “copy” of the cell, and one can see your diaries from then, displayed together with other materials, such as a huge number of knives you produced from junk metal. One thing I have always wondered about was why you were released from prison at all. Wouldn’t it have been easy for the regime to just keep you there?

NT: Most political prisoners don’t get extensions of their terms. So, of course I was scared, but for the most part, you just serve your time and get out.

PG: When do you think this political regime is going to end?

NT: There’s a movement of wives and people coerced to the war zone, who are demanding their husbands be brought back, and they are very brave to do that. I was actually suspicious towards them at first, because they were distancing themselves from politics, saying “No, no, no – we have nothing to do with politics.” But now they are involved in political struggle, because they have realized that Putin does not care about anyone at all – he just claims he does. So, it’s a matter of time until people realize that.

View of “RAGE,” OK Linz, 2024

Nadya Tolokonnikova, Isolation Cell (detail), 2024

PG: If you were born somewhere else, do you think you would have become such a fierce political activist and artist?

NT: I don’t really do nicely with this thought experiment, because I’m a social constructivist. So I don’t know. But, traveling the world and living in different places, I really look at the world as a fight between two forces. One is progressive and hopes for humanity’s freedom; the other one is very retrograde and wants to bring back the old order. No matter if it’s Putin wanting to restore the Soviet empire – crazy stuff – Trump saying “make America great again,” or all the other macho, patriarchal movements like that in Europe, refusing women’s rights, gay rights. I really see the world in almost black and white in this sense.

I love idealistic people, I love their company, and I love the world that they want to bring into being.

PG: Where does your urgency in your projects come from? Couldn’t you pretty much just do your artwork at home, not speak up against anybody, and allow yourself to lead a more comfortable life?

NT: It’s part of my upbringing. My dad is this freedom-loving person, and I was just always drawn to communities that fight for freedom, whether antifascist or anarchist movements, when I was coming of age. I love idealistic people, I love their company, and I love the world that they want to bring into being. I look at the world as a thing that’s going to last much longer than me, and that helps me to overcome my shortsightedness, and my dependence on personal comfort. I’m willing to make certain moves, even though I know they are not going to be good for me, which I think is a personal trait. I also love to combine theory and practice: It’s never enough for me just to think in the right ways, it’s also important for me to act the right way.

Two years ago, I became vegan. At some point, I just realized that it doesn’t work nicely with my overall idealism to eat meat if I’m causing so much pain and suffering to living beings who did not do anything to deserve this pain: living on farms, being tortured, being raped – cows are being raped. So, at that moment, I realized that my deeds have to actually follow my thinking and my words.

Nadya Tolokonnikova, RAGE, 2024, performance documentation, OK Linz

___

NADYA TOLOKONNIKOVA will perform RAGE at the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin at 8pm on Thursday, 4 July. Entry is free without RSVP. Wearing of balaclavas is encouraged but not required.

“RAGE”

OK Linz

21 Jun – 20 Oct 2024