Artist and filmmaker Beth B (*1955) is a legend of the US underground. In the late 1970s, as musicians, filmmakers, and artists flocked to New York City’s derelict downtown, she became one of the foundational figures of No Wave, a radical, DIY, interdisciplinary movement defined by a nihilistic worldview, stark minimalism, dissonant soundtracks, and a confrontational, “anti-everything” attitude. Over a forty-five-year career, B – who describes her current practice as “Now Wave” – has straddled mediums and genres with iconoclastic insouciance. Her early no-budget “B Movies,” made with then-partner Scott B, were noisy punk provocations shot on Super 8 and 16mm, while later music videos – such as the racy, banned-from-MTV promo for Dominatrix’s “The Dominatrix Sleeps Tonight” (1983) – and features, like prescient televangelism satire Salvation! (1987), pushed glossy 80s visual excess to its queasy limits. Through her low-fi documentaries, B has turned an intimate lens on subjects ranging from outsider artists, to drag and burlesque subcultures, to traumatized Vietnam veterans and their children.

B’s latest exhibition, “Glowing,” fills the echoey Betonhalle of silent green, a former crematorium in Berlin, with installations which combine new moving image works with an enveloping soundtrack (composed by B’s husband and regular collaborator, the musician Jim Coleman) and sensorial elements – flashing strobe, flickering projections, a sandbox – to offer sometimes dreamlike, sometimes nightmarish reflections on life and death. The exhibition is accompanied by a filmographic retrospective, plus performances featuring many of the artist’s regular collaborators, including Lydia Lunch, Coleman, writer Nick Flynn, artists No Anger and Ida Applebroog, and the bands Human Impact and This Wilderness. Experienced together, the program is a dizzying deep dive into an artist who has never stopped raging against society’s limits, and who, despite the sometimes disorientating diversity of her prolific output, has remained consistent in her key thematic preoccupations – power, sexuality, desire, suffering and, behind the howls of fury, hope.

Rachel Pronger: The film series at the center of this exhibition, Glowing (2024), is immersive and intimate, but it’s also deeply political. By having your audience listen to the autobiographical stories of six different artists – No Anger, Nick Flynn, Robert O. Leaver, Little Annie, Vincent Dubuis and Evelyn Frantti – you’re asking them to inhabit perspectives that are likely far outside their own: different genders, sexualities, experiences of disability …

Beth B: So much of the world today is based on snippets from social media. We are told that what we should strive for is to take the best image of ourselves that we can and put that out into the world. My work is the opposite of that. It’s about going deeply into a place of vulnerability, for the possibility of discovery. What is life but that?

My films and installations have always been about the other, the outsider, the misfit, the disturbance that people don’t want to look at. Sometimes, the disturbance is ourselves! That, to me, is critical. My goal is look at those who sometimes we turn away from, usually in fear of the unknown, of uncertainty. How do we relate to someone who is disabled? How do we embrace their language, as opposed to imposing our language upon them?

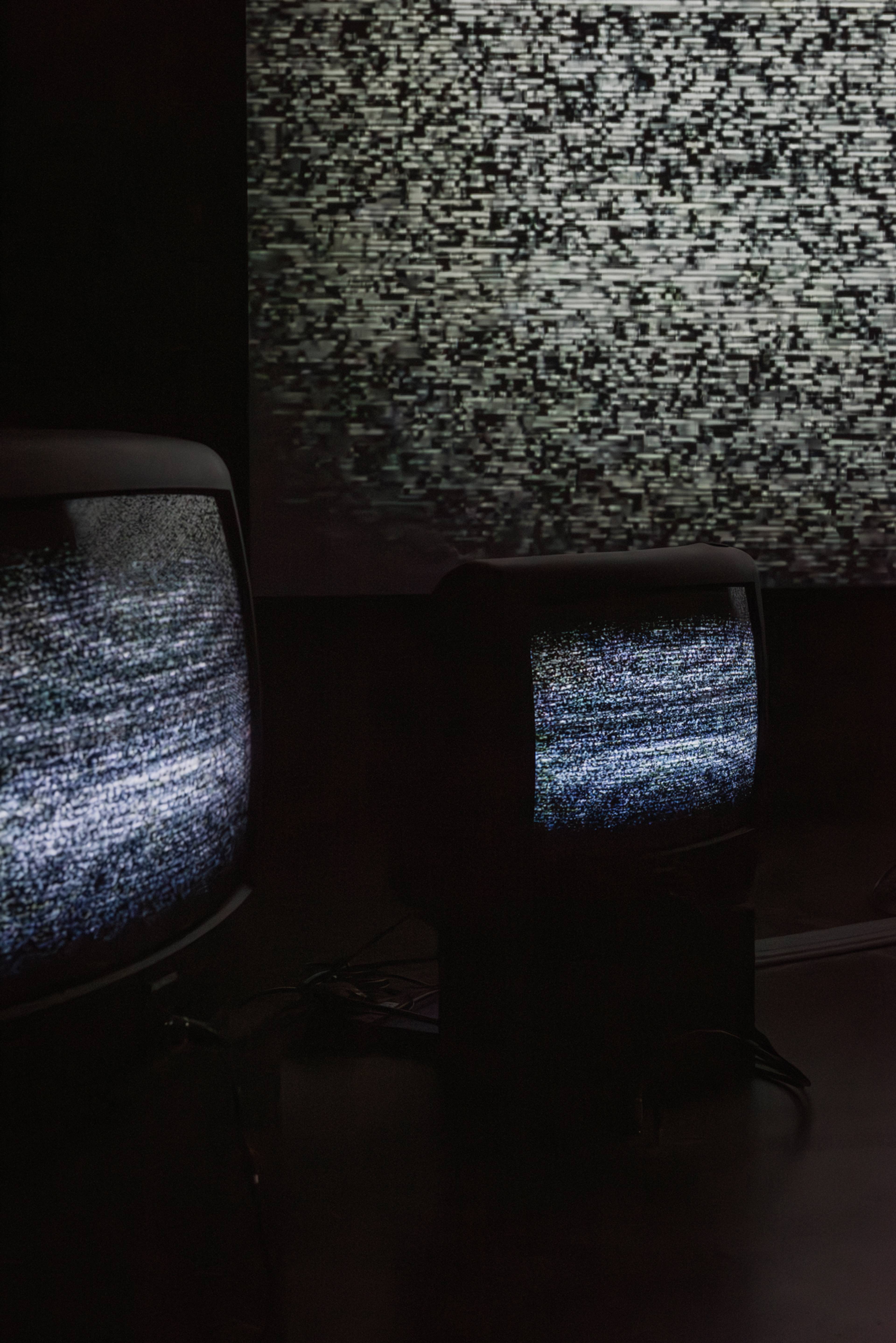

Beth B, Glowing, 2024. Installation view, silent green, Berlin. © Lola Coleman

RP: Your film installations often include immersive elements – a swing for Sorrow, a sandbox for Children of Wonder. How do you hope that visitors will experience these as they move through the exhibition?

BB: I wanted this exhibition to create a kind of circle from the “no” to “now,” and my hope is they will find something within themselves that is triggered by each of the rooms. When you enter the exhibition, you’re in a tunnel, which is a little bit like a birth canal. Birds are coming, the baby is taking flight. But they’re dark birds, a little demonic, because the world is a cruel place that can rob young people of their innocence and purity. Society takes over and starts putting them in chains.

Sorrow is about the world we live in, where so many people are affected by cruelty and violence by other people. That’s why, with the installation, I give viewers the freedom to be in that space, swinging towards a swing that is fixed, representing, in a way, the inability of children to change their experiences when they’re young. Perhaps things were not so kind to them, and they often weren’t able to swing freely. I want to offer that to the audience.

For Children of Wonder, I imagined a big sandbox, light, and sounds of kids when they haven’t yet been beaten down. Most of the voices we hear belong to six-to-eight-year olds, and I want people to just go back to that place, lying in the sand and seeing the glittering lights above, to re-inhabit places of ourselves that we might have lost to the structures that have been placed upon us. In general, the exhibition is really looking for places to release that, to come back to a place of wonder without judgment. That, in a way, leads us to recognize our past and the things that were terrifying or disturbing. Here is a place to try to reconcile and transform ourselves.

Views of “Glowing,” silent green, Berlin, 2024. Both © Daniel Rodriguez

RP: I’m interested in this conversation about “No” and “Now” Wave, circularity and continuation. Having the exhibition and the retrospective together elicits a comparison with your early punk films. There is a sense of that anger, but also of calm, even though the themes remain constant.

BB: The themes are the same: power, control, domination, submission, rage, the desire to inflict upon others the pain that we have experienced ourselves. That said, I do feel like I have, in a way, been able to transform myself, to find a fuller, richer way of living, to let go of that rage. I don’t want to live my life like that. Of course, I think we all revisit those places within ourselves. They’re part of us, and I embrace that. It’s what formed me. In the late 1970s, when I had no clue as to why I was so enraged. I think that’s the creative act, this sense of catharsis.

RP: How did this collaboration with silent green come about?

BB: Oddly enough, I didn’t realize it, but I met Tina and Jörg [silent green co-founders Bettina Ellerkamp and Jörg Heitmann]at the Berlinale in 1987, where I was showing my film Salvation! They were young journalists and they interviewed me in my hotel room, while I was in bed with the film’s star, Stephen McHattie. It’s funny because, in many ways, I feel that my life, my career, my creative interests keep circling around to the past, yet I am 100% in the now. No Wave is my past, but informs my present. That’s why I really wanted to do this exhibition. Tina and Jörg are connected to my history, but they also helped me see how I have transformed over the years.

It’s very rare that an artist gets to create something for such a dramatic space, with such history. Jim [Coleman] and I had been working on a series called Near Death, and this seemed the perfect place for those works. I had done two of the Glowing films, but I wanted to keep expanding. In April, we came to visit and see how I could connect with the crematorium as a space, but also build an exhibition which would speak to my own history. I really wanted to offer a kind of journey, to show how it’s possible to navigate the struggles of life positively, in a cathartic or transformative way.

Music also inspires me tremendously, so another dimension was to bring in live performers, beginning with the band Human Impact for the opening. Instead of it just being a projection on the wall, to actually have Jim and Chris Spencer performing in front of an audience really adds another immersive form of intimacy. Cinema and installations are fantastic, but to actually have a human body, an entity and voice connecting with an audience, is a different experience.

Still from Beth B, Call Her Applebroog, 2016, 70 min. © B Productions, Inc.

Still from Beth B, Salvation!, 1987, 80 min, with Stephen McHattie and Dominique Davalos. © B Productions, Inc.

Still from Beth B, Salvation!, 1987, 80 min, with Viggo Mortensen. © B Productions, Inc.

RP: Collaboration has always been part of your practice, but it seems to be only becoming more integral to your work over time.

BB: I had to evolve into this. When I first started to make films, I didn’t want that connection. I was so confused, I had a steel plate up in front of me, to push people away. What better way to push people away than to scream at them, smash them in the face, and be loud and aggressive? I needed that, coming from a family situation where I wasn’t allowed to express myself as a young girl. My work is still very tough, but it’s much broader. It’s a relief not to walk around in that rage anymore, but it’s taken a lot of therapy, and a concerted effort to be honest about who I am, not to be afraid to be vulnerable. I didn’t want anyone to know who I was, because I thought I was not acceptable in mainstream society.

RP: Did that feeling of stifled rage come from that particular context where you grew up, the US suburbs of the 1960s? And did arriving in New York allow a place to express that anger?

BB: I was already expressing that anger, but I was also being smacked down for it. When I got away from my family of origin, I was able to start exploring that rage and embrace it. For women of that era, of my mother’s age, the kind of families that were acceptable were nuclear, male-dominated families. My father was an Austrian patriarch, my mother was the good housewife. But, at a certain point, that whole structure broke down. As a young girl, I understood that was not going to work. So, in a strange way, it fueled my wanting to create my own path. For women to be able to do that, even today, is extremely hard.

I remember that the first time I was in Berlin, in the 70s, men wouldn’t recognize me as a filmmaker. They wouldn’t even shake my hand because I was female. We’ve come a long way, but I would just encourage all young women to open their mouths and say what they think. Even if you think it’s not acceptable, it’s important to speak your mind.

RP: It’s that strident perspective that seems to be bringing a new audience of young women to your work and that of your 70s and 80s peers. How much like a “scene” did No Wave feel at the time?

BB: There were definitely a lot of people in New York City at that time who wanted to destroy everything around them. New York was a perfect playground for that, because it was a demolished city, and, politically and socially, everyone had left it. President Ford basically said, “Fuck New York.” They wouldn’t even fund it anymore. For us as young people, it was great. We could break into buildings that were abandoned, we were surrounded by rubble – it was perfect.

Still from Beth B, “The Dominatrix Sleeps Tonight,” 1984, music video, 4 min. © B Productions, Inc.

Still from Beth B, Visiting Desire, 1996, 70 min., with Lydia Lunch (left) and Shannon O’Kelley (right). © B Productions, Inc.

RP: This very much feels like a parallel with Berlin at the time.

BB: Berlin was absolutely the sister city of New York, and that’s why I felt so at home here at the time. It was definitely a like-minded atmosphere.

RP: How possible is to create that kind of energy now, given that many major cities have become unlivable for artists? Young artists are really encouraged to go down this route of corporatized art, of self-branding …

BB: Today’s art scene is absolutely a marketplace, and young people I know are geared towards satisfying that. In my mind, you should always work against the system, not within it. I think I’ve always done that, in that I’m not a specialist – I’m anti-specialization. What’s most important is not the form, but the idea. The idea leads me to figure it out. Is it film? photography? sculpture? I always go against the idea of pushing myself to be a filmmaker, or an installation artist, or whatever. When you’re thinking in that way, you’re limiting your imagination.

That’s why I love Glowing, because it’s all of these things. Whatever the idea is, that is what’s dictating it. I have sculpture, portraiture, film, narrative … It’s kind of hybrid, creating it’s own form. I don’t know what it is! It’s not about where it’s going to be, what it’s going to be, what form it’s going to take. It’s the process.

RP: Funding must always be a question with that kind of outsider approach.

BB: Always, always, always! I decided years ago to not depend on any institution. There isn’t any government funding in the US anymore. I don’t have money, I just make my films with pennies. I really went back to Super 8 filmmaking in a way – no budget. I use my iPhone a lot of the time, or a GoPro. Now, we have a drone, so that looks fabulous. It looks like we have a lot of money, but all the films were made for a few hundred dollars. I basically self-fund everything. For my last three films, I crowdfunded with Kickstarter campaigns, because I don’t want to be bound to or prevented from doing what I want to do. We’re lucky at silent green, because the entire exhibition was funded by the German Federal Government.

You can totally let money control you, but I’ve always made films, whether I had the money or not. Young people say, “Well, how can I do it? I have no money?” I’m like, “Fuck you!” Because, I’ve done it. I’m a fucking old lady. I still do it because, if you’re passionate enough about your ideas, you will find a way. I learned that through guerrilla filmmaking in late 70s, and that’s been my motto all along. Just do it. You can sit around your whole life for somebody to say it’s a good idea. I don’t need that validation from anybody else – I give that to myself.

Beth B at her exhibition “Glowing,” silent green, Berlin, 2024. © Daniel Rodriguez

___

“Now Wave: Beth B – Glowing”

silent green, Berlin

16 Aug – 25 Aug 2024

The exhibition soundtrack can be streamed online and is available for purchase from play loud! productions.