Little Pink Book (2025) is a new novel by Olivia Kan-Sperling about a lonely barista-blogger with tiny poems and milky drinks; how she gets turmeric-honey on her pinafore and something stickier somewhere darker. At night, at the club, she twirls a cocktail parasol in her Peach Oolong Martini and wonders if a sarcastic white-collar professional thinks her dress is silly. She feels stupid and a pulsing sensation like there’s a clock or thick cloud of cicadas, but, like, inside her …??

This is Olivia’s second book. Like her first – Island Time (2022), about a character named Kendall Jenner longing for “Lil Peep” on an island in a video game – it’s hard to explain. Olivia makes words blush. More on that in our conversation below, but, basically, there’s a special sparkly stress to her style, a fluttery tension at the edge of language, like the writing is flirting with the page. Except, “instead of an unfurling flower,” it presents “a skull with worms inside eye sockets in the soft white foam.” A reader might feel teased by such swirly syntax. It’s confusing. You try to gloss this literature and it’s like, “Oops...Sorry...” (p.95)

So, what if, instead of settling for story, meaning might be mounted by letting implication slip inside a clause arching to bend over a comma? Not to be desperate to make plot come or need to nail narrative, but to straddle big, loaded diction with perfectly tight prose that, somehow, is also so slippery and full of foreign-feeling phrases splaying their logic and wrapping pillowy sentences around probing questions, like, how do you have text?

“Here’s your poem,” she said with a flash of attitude. “I hope you like it.”

“这是你的诗,”她带着一丝态度说道。“希望你喜欢。”

(⸝⸝๑ ̫๑⸝⸝)

Cara Schacter: Little Pink Book used to be littler – a piece of fan fiction for a fake documentary. Can you explain the start?

Olivia Kan-Sperling: My friend [artist] Diane Severin Nguyen had a show at the Rockbund Museum in Shanghai in 2023, and asked them to commission me to write fan fiction about her work instead of a critical text. The film she was showing, In Her Time [later part of the 2024 Whitney Biennial], is this music-video-style docufiction about an actress cast in a movie about the Rape of Nanking. It’s about repeating trauma and the aestheticization of sexual violence in service of national identity formation.

It seems boring and patronizing to just “interpret” someone’s work. Plus, I know so little about China that anything I’d write would necessarily be a mistranslation. So, I was like, okay, what’s the most wrong way to approach this? And it was to begin with softcore rape porn – a staple of fan fiction.

Spread from Little Pink Book, 2025. Courtesy: Archway Editions and Olivia Kan-Sperling

CS: The subtitle is a bad bad novel. What do you mean by “bad bad?”

OKS: I love “bad” writing: amateur or “folk” literature, like fan fiction or text-based roleplay logs or self-published booklets on alien encounters; but also the kind of show-offy experimentalism deemed tacky today – metafictional mediacore novels like Infinite Jest [David Foster Wallace, 1996].

I was also wondering about the ways in which writing is “bad for you” and other people. Imagination is fundamentally antisocial.

And it’s particularly antisocial that I like using words the wrong way. I love the term “abuse of language!” The book abuses language and the protagonist, Limei, equally. Which is to say, language is the main character.

CS: What does Limei look like in your head?

OKS: I can't write someone if I don't know what they look like, so I usually “cast” celebrities as my characters. But a live-action Limei isn’t possible. She’s a gif or cartoon, maybe the Chill Beats to Study to Lofi Girl. Little Pink Book is superflat, stylistically. Emotions don’t come from a deep inner place, they’re more like stickers.

CS: I don’t watch cartoons, but I do take Adderall, so I can relate to an affective spike being “administered.”

OKS: Exactly! Like “canned” feelings added in “post,” or a laugh track. I wanted Limei to have an emotion – or for it to say she has an emotion – and then create this feeling like in a video where an effect has been edited in, like FAIL or Sad Trombone sound or cartoon-tear-dripping-down-face. That style is common in Asian media. I wanted to translate that aesthetic of doubling, of someone telling you how to respond, onto the page./

CS: Those effects are funny. Is your book “ironic?”

OKS: My writing inevitably has an ironic twinge because the melodramatic moments I’m fascinated by – “feeling misunderstood” or “falling in love” or “wanting to die” – are tragic, but also funny!!

So there’s irony, yes, but not sarcasm, which is mere negation: ungenerous and stupid. I wanted to parody women’s romance novels and the tropes of postmodernism that signal intellectualism, like “what’s-even-real?” Truman Show-type narratives. Both are deep and dumb at the same time.

Writing can be the most psychedelically abstract, virtual, flexible, fascinatingly solipsistic medium – but it is also impoverished. Words are nonsensical substitutions for the things that they are.

CS: Some words are printed in pink, which I read as like when we use tildes to ~flirt~. Is that right? Like some kind of grapho-textual winking gesture, or like when guys text you stuff with invisible ink …

OKS: Exactly! The pink words are words that blush. Pink is shy and carnal, the shade of shame, but also the most corporate-consumerist, soulless color.

I generally use words more like images, so I was excited to do a “Chinese” book. Although they’ve become abstracted with time, written Chinese characters still show their pictorial origins: The word for tree looks like a little tree or whatever. “Calligraphy” means “beautiful writing.” The trope of the oriental as decorative was another inspiration. I wanted the prose to be “calligraphic” – pretty!

But overly pretty and sensorial writing is BAD. We call it “purple prose”: hypervisual extended metaphors, alliteration … All of which I love. I suppose I could have made words lavender, but the book’s title was already a super dumb pun on Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book [1964], the ultimate “CHINESE” book for Westerners. I liked the idea of writing a novel that’s also didactic, an aesthetic manifesto.

So, instead of purple-colored prose, I decided to whiten Chinese red into Barbie pink. It’s a very obvious book. It hits the reader (and Limei) over the head with itself over and over again. Which is itself a cartoon aesthetic.

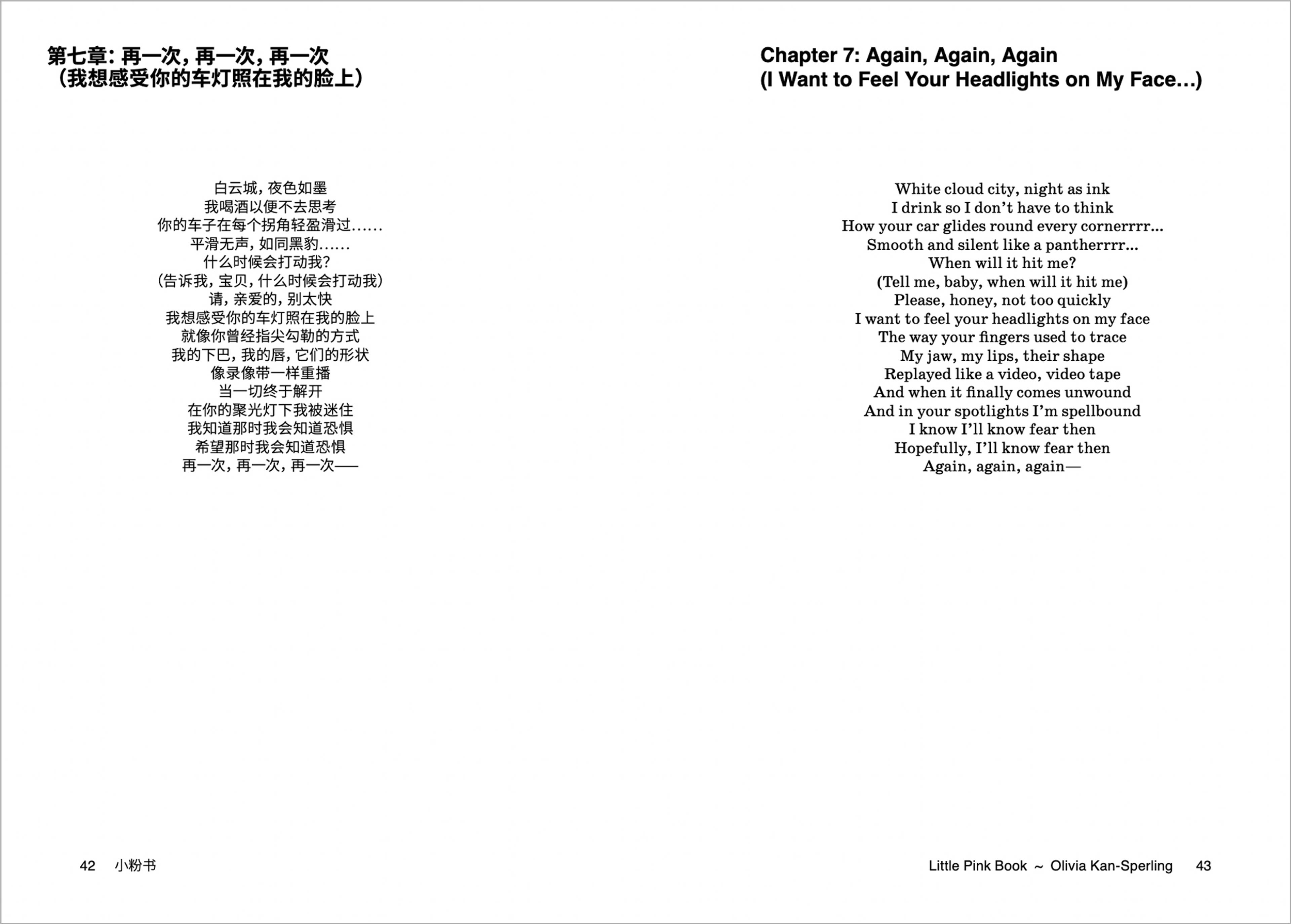

Spread from Little Pink Book, 2025. Courtesy: Archway Editions and Olivia Kan-Sperling

CS: Characters’ T-shirts say stuff like: “Oh, and Can You Put a Surprise On That?” and “Crouching Tiger, Crying Kitten.” Also, the book is printed as a bilingual edition, so every other page has a chunk of language incomprehensible to non-Mandarin readers. I guess my question is about the aestheticization of translation/mistranslation. Or text being “worn,” as in ruined.

OKS: The Chinese e-novels I was inspired by were these cool amateur English translations. I’m less interested in machine mistranslations than the human touch that creates sentences like:

The man’s mind kept shaking Hu Sen’s words.

“Madam, we went to the cemetery today.”

His words stimulated his neurons. His heart felt like it was being torn apart. It was so painful he wanted to dig it out.

“Mo Cangyun… it hurts…” When she finally couldn’t hold it any longer, she opened her mouth and sobbed softly.

However, her words were useless.

[From the short story “Awesome Hubby is Online,” published on Babel Novel]

I grew up hearing family speak Mandarin, but understanding only a couple of words. Chinese to me is something halfway familiar and foreign, between sense and a melody. I wanted the bilingual element to be a decorative feature that also reminds you that there’s something alien, incomprehensible, and sensorial about all language.

AliExpress-English, the language of drop-ship-shopping and dollar-store stationery, is amazing – but Equinox ads and Vogue copy can be equally so, if you read them the right/wrong way! Practicing misreading is important, creative, and juvenile. It keeps language alive!

The idea that an author can “create” a character and “know” them seems stupid, when we don’t even know ourselves.

CS: Words repeat in LPB. Some, like “sticky” and “tight,” register as obvious innuendos, but other motifs feel more covert, like the repetition of “click” and “perfect.” For example, in Chapter 36: “Help, I’m Pregnant”:

Inside her mouth, they clicked into place, and everyone heard herself pronounce them perfectly.

“Perfect clicks” interest me. I was thinking about “clicking” (on computers) being our “programmed” way to access/navigate the world/web – a theoretically expansive gesture that actually, texturally, feels quite cold and terminal. So desire collapses into a tiny sterile jolt or something being shut.

More ominous clicking in the book:

...she cast one cautious eye behind her, she was alone. Only the sound of cicadas.

Also, in Island Time, “perfect click” comes up when Kendall compares losing her virginity to cheerleading – a metaphor, maybe, for coming together in a kind of split.

OKS: Yes! “Click” is a machine word. I studied computer programming, where language can function without mistranslation – but that’s not true of human communication. When people say “we just clicked,” they mean mutual emotional fluency. That’s the romantic ideal. But Limei is a bad bad reader … everything gets lost in translation for her.

Writing can be the most psychedelically abstract, virtual, flexible, fascinatingly solipsistic medium – but it is also impoverished. Words are nonsensical substitutions for the things that they are. In college, I got into all the theory about how language is always misfiring, which is cool, but the real miracle to me is that humans can understand each other at all.

Spread from Little Pink Book, 2025. Courtesy: Archway Editions and Olivia Kan-Sperling

CS: Your narrator is kind of scary – third-person omniscient with this freaky overlord attitude. For example: “He sat … there. There, over there, at a low table.” What’s up with the narrator’s vibe?

OKS: I was thinking of pop-up ads, musical scores, various types of overlay – the narrator is like a cruel film director puppeteering the protagonist to act self-destructively for our entertainment, the divine “voice from above” that is internalized as a “voice in your head.”

But maybe this narrator isn’t actually omniscient; maybe the reader isn’t given access to the “real” Limei. By being-written, she has been flattened into this cartoon whose real form exists in an elsewhere (China?) that is illegible to me. The idea that an author can “create” a character and “know” them seems stupid, when we don’t even know ourselves.

Language lives above/outside and inside us; it’s intensely personal and the most universal, communal human structure, the way we interface (or fail to) with ourselves and others – that tension is basically the plot of the book.

*

Later, Olivia sends a voice note with a few follow-up thoughts about lyrics, how language is her horse, and sadness – which, by the way, is Limei’s favorite food (being sad is).

OKS: Um, I really, really liked – oh, my other comment was just – [breakfast food] – never mind. But anyways I really liked your description of the incident on your parents' staircase. The looking downwards thing – a sense of gravity – made me think of this thing I was reading … from Richard III [Shakespeare, c. 1592–94]. Okay I’ll actually just read some right now because I have it.

Each substance of a grief hath twenty shadows

Which shows like grief itself, but is not so;

For sorrow’s eye, glazed with blinding tears,

Divides one thing entire to many objects,

Like perspectives, which rightly gazed upon

Show nothing but confusion

That idea – the sparkling perspective, the shattered shimmery world – made me think of your memory about being at the top of a ski slope as a child and feeling, for the first time, sadness for no reason. When you’re sad is when language gets interesting because that’s when it stops working and breaks into these sparkling pieces of confusion. I like words with twenty shadows. Life is very sad so you can only deal with that through humor I think … Anyways in terms of inventing a mode of expression adequate to one’s interiority – one’s ~*very special*~ interiority – not sure how that happens. I just love writing so much!!! And sometimes it feels like words love me back, and our relationship is like … a cowboy and a horse? I love words because they’re genuinely abstract and infinite in this way that images are never. Even a surreal or abstract image is fixed and inflexible, and kind of stupid, so stupidly material. Whereas with words – they’re much weirder. The expression, “Not being able to see the forest for the trees,” for example – is a visual phrase. I see some hazy collage of emoji trees. Maybe real trees. But it never actually resolves into a clear retinal image. I see the words, too: “FOREST” “TREES.” Text operates in this hallucinatory in-between space that can create something impossible; like, an impossible not-image … On the other hand, this also makes words so shitty and lo-fi compared to pictures. The relationship between words and music is also interesting … Island Time is a romance with “Lil Peep” which is a romance with what/who isn’t there or can’t be pinned down. And in Little Pink Book, I invented these really, really, dumb pop songs – but fundamentally, don’t all lyrics look dumb on paper? You need music to animate them. Once there’s melody, it’s beautiful and makes you feel all these things. But when they’re just on the page, even cool songs still kind of look, like, ugh. That’s why pop music is amazing, because it makes you feel something even though it’s stupid. Lyrics, I guess, are another example of “pink” language – something meant to be sensorial. But, ya, seeing lyrics written out is uncanny, ghostly. And I’m always interested in that – the shadows or reflection, the thing that’s not quite there, in desire for example … but then sometimes there’s a rupture and it – something – breaks through. Uh … sex? Haha.

她低下头,腼腆地转动着小小的鸡尾酒伞。她感到 自己处在一个无论如何都将推进的场景中。

“除了张开嘴,任凭从遥 远处传来的词语填满,又能做些什么呢?”

“你觉得我的裙子很傻吗?我觉得......愚蠢......它不太......”

“不,我喜欢,挺好的。”

“我是说,我不太......”

“也许你应该靠近一点——这里。”

“如果你觉得......好吧......”

“我们去屋顶吧,好吗?我想抽烟。我们可以......在那里多聊聊。”

“我觉得......”

“...”

“...”

“上海的夜晚很美,不是吗?看——那边。电视塔。东方明珠。你看

到——它在跳动吗?粉色的。”

She looked down. Demurely, she twirled the tiny cocktail parasol. She sensed she was inside a scene that would move forward no matter what.

What else was there to do but let her mouth fall open, fill with words put there from far away?

“Do you think my dress is silly? I feel…stupid…it’s not very…”

“No, l like it, it’s nice.”

“I mean, I’m not very…”

“Maybe you should come close—here.”

“If you think…well….”

“Let’s go to the roof, okay? I want to smoke. We can…talk more there.”

“I feel…”

“...”

“…”

“The nights in Shanghai are beautiful, don’t you think? Look—there. The TV Tower. Oriental Pearl. Do you see—how it’s pulsing? Pink.”

___

Olivia Kan-Sperling’s Little Pink Book will be published by Archway Editions on 5 August 2025. Beginning 30 July, the week-long launch event *NIGHT DREAMS LIBRARY KARAOKE READING SCENE* will take place each evening from 8:30 to 11:30pm at Earth (49 Orchard Street, New York, NY, 10002), accompanied by a mood-setting hypnosis visualization. The event will also be livestreamed.