While modern abstract painting aspired to pure, self-referential forms, Peter Halley began in the early 1980s to combine the pure geometries of the square and the line to critique the impulse toward rationalization and social control. Amid the intensification of algorithmization and a new generation of surveillance, a reawakening of public interest in postmodernism is bringing Halley’s painting, recently the subject of a retrospective at Mudam Luxembourg, back to the fore.

Noemi Smolik: Do you think about yourself as an abstract painter?

Peter Halley: I don’t think of my paintings as abstract, I sometimes use the word “diagrammatic.” Back in the 80s, what I wanted to do was to take the language of 20th-century abstract painting and use it to diagram the nature of space in contemporary society. So, the abstract square became an enclosed cell. If I put bars on the square, it became a prison. I connected these squares, that is, these prisons and the cells, with thick lines that I called conduits. I was trying to map the kind of highly geometricized space we live in.

NoSm: In the classical understanding of modern art, geometric, abstract forms are not supposed to have associations with any external subject. So, when you referred pure geometries to spatial objects, this contradicted the modern understanding of abstraction.

PH: Right. But in my case, I was diagramming things that existed in the human-made world. Not specific things like telephone wires or plumbing pipes, but rather the underlying abstract structure that all these things have in common.

I remember, back in the 80s, somebody came to my studio and said, Peter, why don’t you just paint a suburban house with an electric line going into it, so you can see that there’s a television cable going into the house? And I said, I didn’t want to do it that way, I want to create a model for how the system works, not a specific example.

View of “Peter Halley. Conduits: Paintings from the 1980s,” Mudam Luxembourg, 2023. Courtesy: the artist and Mudam Luxembourg. Photo: Mareike Tocha

NoSm: Should we understand these forms as more like models, then?

PH: Yes, based on the idea that permeated the late 20th century, as Baudrillard put it, that the model precedes reality. The example I always use is McDonald’s restaurants: They’re all the same, they come from a predetermined model, they don’t come into existence as unique entities. My prisons and cells are all the same, but they’re meant to represent a generic idea of enclosure or isolation.

NoSm: When you talk about the square, everybody thinks immediately of Kazimir Malevich. What did he and his square mean for you when you started to develop your models?

PH: When I was a student in the late 70s, Artforum was run by a guy named Joseph Masheck, who was publishing a lot of material on Russian Suprematism. So, Malevich’s square and that kind of geometry was certainly something I was familiar with. But at the same time, the square was such a prominent part of Minimalism that you might say my experience of Malevich was filtered through Donald Judd, Frank Stella, or Agnes Martin, all of whom depended on the square.

NoSm: We have to be aware of how important Malevich’s square was for the development of art in the US after the Second World War.

PH: Yes, but I don’t believe his work was known in the US before the 50s, when there was a big show at MoMA. It’s funny, now that you mention it – even Andy Warhol’s portraits are squares. So, the square became this key iconographic element during the 60s and 70s. Not so in Europe, where there was not this kind of obsession.

I literally wanted to transform the meaning of a geometric form from one associated with idealism and ahistoricity to one associated with an idea of confinement.

NoSm: Alongside the square, could you tell me about the writing of Michel Foucault as a source for your art-making?

PH: Let’s imagine one of my early paintings, with either a cell or a prison and a plain background. I literally wanted to transform the meaning of a geometric form from one associated with idealism and ahistoricity to one associated with Foucault’s idea of confinement. I covered all the squares and the cells in the prisons with this cheap stucco material called Roll-A-Tex to give them the feeling of architecture, as if these forms were actual structures you could be inside.

NoSm: The very un-earthy colors also make your paintings look artificial.

PH: Exactly. And I’d like to remind people that, in the early 80s, there was a strong movement challenging the idea of nature as a referent. Richard Prince’s idea was not to take a picture of the landscape, but a picture of a picture of the landscape, so that media would supersede nature as a referent. I wanted to get rid of naturalistic color – and fluorescent color, the Day-Glo color that you can see in most of my paintings, seemed to supersede that idea of natural color.

NoSm: Do you think of your paintings as reflecting the overall obsession in industrialized cities with abstract forms?

PH: Actually, what I had asked myself was, why did geometric abstraction reappear in Western art in the 20th century? I came up with the argument that it actually reflected and even celebrated the increasing geometricization and rationalization of space in our society, not just in New York or other cities – but in the entire world. The internet is the apotheosis of this development.

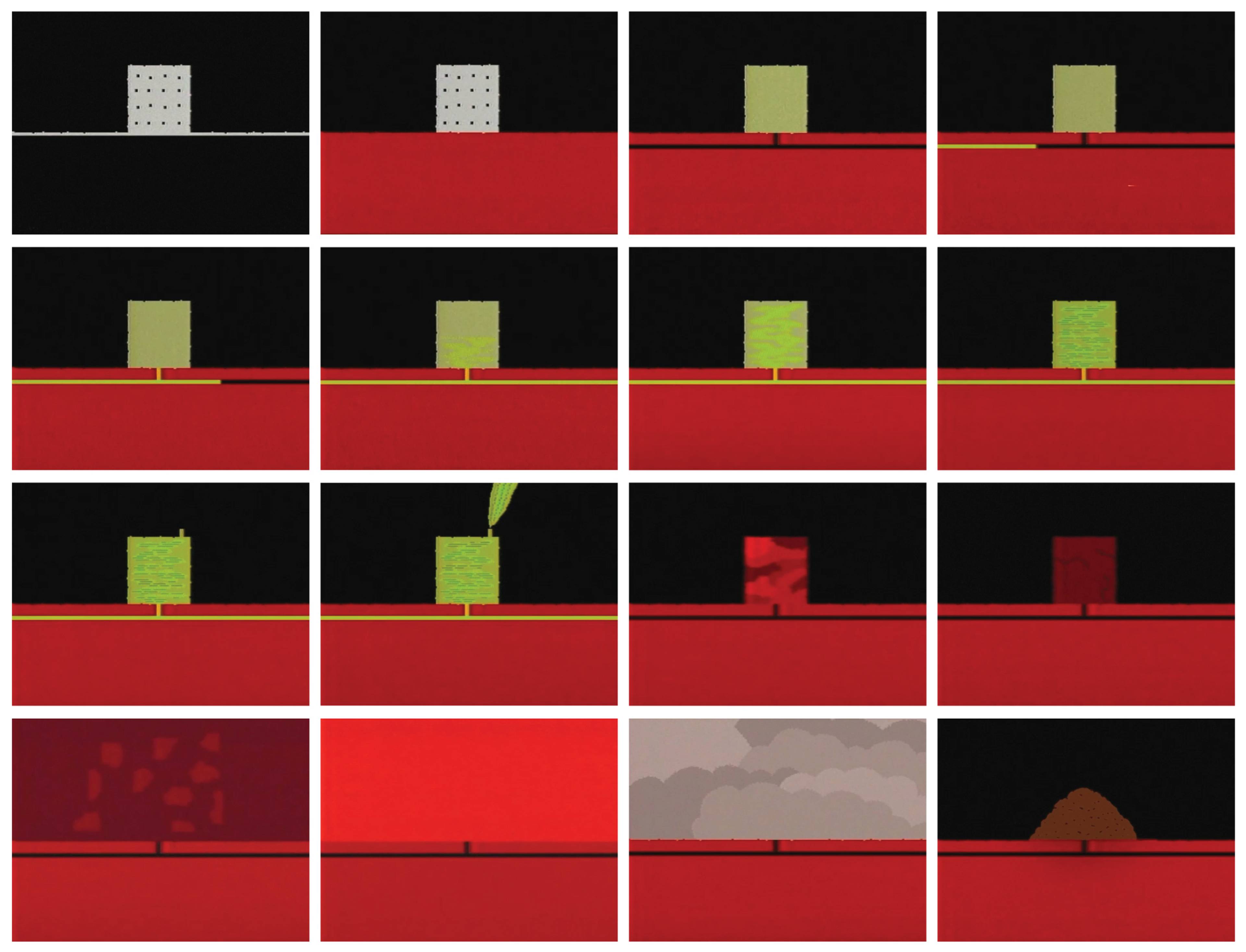

Stills from Peter Halley, Exploding Cell, 1983, video, 8 min.

NoSm: Does this control or this need for control have something to do with a compulsion toward geometrization?

PH: Yes, these systems govern our lives, how we move, how we communicate, even how we think.

NoSm: The Minimal and Conceptual art of the 60s and 70s was dominated by geometric forms. How do you explain the break in the 80s, when artists started to be interested again in figurative images?

PH: Yes, these artists imagined geometry as a referent without a reference. An artist like Donald Judd said that his work had no referents, that his signifiers had no signifieds. It was a wonderful, if failed, linguistic experiment – and it had a big influence on me. But by 1980, translations of writers like Roland Barthes and Jacques Derrida began to appear in the US. They took just the opposite point of view, not that the signifier has no signified, but that it has an infinite number of possible signifieds. I think that generated a huge shift in artistic practice of all kinds.

NoSm: Here in New York, you mean?

PH: Well, almost everywhere. The same thing happened in Europe with figurative painting and Neo-Expressionism. There was almost a rush toward signification, to say that forms had signifieds, whether historical, allegorical, political, or psychological.

NoSm: In 1996, you and Bob Nickas founded index Magazine. Did you understand the publication as a continuation of, or a departure from, the ideas you were working on in your painting?

PH: I felt that the New York art world had lost a lot of energy in the 90s, and I was eager to do something that would connect me with people who were doing interesting things in other fields like music, film, and fashion. In a way, the magazine seemed to me like an extension of my work as an artist. It was another way of making connections – the same thing I was doing with the conduits in my paintings, except in real life.

Covers of index Magazine, 1996–2001

NoSm: There is an ongoing revival of public discourse about postmodernism, after a long period when discussing it was somehow taboo. As you were a part of this movement, together with Richard Prince, Cindy Sherman, and the whole Pictures Generation, what does postmodernism mean to you from today’s vantage point?

PH: I saw a great exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum about postmodernism in 2011 [“Postmodernism: Style and Subversion 1970–1990”]. When I walked through, I almost thought it was the story of my cultural life, seeing work by architects like Rem Koolhaas and musicians like David Bowie and the Talking Heads. The thesis was simply that postmodernism was a critique of modernist idealism. And even if I didn’t see it quite so simply in the 80s, as I look around at the paintings in my studio today, they’re a kind of critique or even a parody of artists like [Josef] Albers or Malevich or [Piet] Mondrian. My work borrows the language of those modernists, then turn it to a different, more skeptical purpose.

NoSm: Why did you produce paintings that are colorfully cheerful and full of light, qualities one usually associates with positivity, when their subject is more critical and pessimistic?

PH: Well, in the 80s, they were much more austere. All the paintings in the Mudam exhibition and the catalogue are in Day-Glo, but there’s also a lot of black. They have a kind of austerity that ended in the 90s, when I began to use metallic and fluorescent paint along with Day-Glo paint, and the images became more hyperactive.

I think my work has almost followed the development of the World Wide Web. In 1985, we had one wire leading into a house for cable TV. But by the time you get to the internet, you no longer have that singular source of information around you; instead, you have connections going everywhere. And the paintings I made in the 90s, I think, tend to reflect that.

When I first came to New York, you could almost recognize a painter by thier surface: I was sort of inspired by Andy Warhol to just satirically roll on my texture instead of creating it by hand.

NoSm: Did you perhaps become less of a skeptic?

PH: Oh, hardly. The challenge that I was facing as a younger artist was the infrastructure of the digital age. How are things connected? What is the whole organization behind the computer terminals we sit in front of? For younger artists in 2023, I think, the issue is social media and the huge psychological and social implications of digital media. If I were thirty-five today, I hope that’s what I would be thinking about.

NoSm: In your paintings, there’s also a degree of humor and absurdity.

PH: I’m really glad you see that, because I think my work is very funny. I mean, even the idea of putting bars on a square and calling it a prison is almost a childlike gesture. To take another example, ever since the early 80s, I’ve used this funny Roll-A-Tex texture, which itself was satirical, because when I first came to New York, you could almost recognize a painter by the surface of her or his painting: Helen Frankenthaler had a certain surface, while Ralph Humphrey painted with a palette knife, the paint was really thick. I was sort of inspired by Andy Warhol to just roll on my texture instead of creating it by hand.

NoSm: At that time, there was a whole ideology about brushstroke and texture ...

PH: Yes, arriving in New York with the rise of New York Neo-Expressionism was really a nightmare for me. I felt it was so nostalgic. As someone who grew up with Conceptual art and Minimalism, it felt to me like the whole art world had gone crazy.

NoSm: You’ve been working on these geometric paintings continuously for forty years. What has changed in your thinking or your approach, and what has stayed the same?

PH: I think that, for most artists, as they get older, their paintings become more self-referential: They become, not always and not entirely, about the work they have already made. What’s interesting to me about my paintings, at this point, is that I started with this very small set of signs – a prison, a cell, and the conduits connecting them – and all this time later, I’m still playing with those basic elements. It’s almost like playing a chess game for four decades: The pieces don’t change, but with each game, the result is different.

Portrait of Peter Halley in front of Blue Cell with Triple Conduit 3, Polaroid, 1986

___

“Conduits: Paintings from the 1980s”

Mudam Luxembourg

31 Mar – 15 Oct 2023