I first met Simone Forti (*1935) in Los Angeles in 2012 with the artist Luigi Ontani, a friend of hers since the 1970s. We paid a visit to the grave of her dad, Mario Forti, in Westwood Cemetery, a stone’s throw away from where Simone used to live. At that time, I was unaware of how crucial Mario had been in Simone’s work. An avid reader of newspapers, when he passed away in 1983, Simone initiated in a kind of catharsis “News Animations,” a series in which the artist analyzes the relationship between language and physicality, starting with printed news.

Since then, I have re-met Simone many times, and over the years, we have collaborated on several projects, most notably three books – her latest, New Book, was published last year. Her practice lies at the intersection of dance, writing, drawing, sound, and poetry, generating a unique vocabulary both poetic and political. An exhibition of her drawings, photos, and videos at Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan neatly sum ups the choreographer’s lifelong query into language and movement, where the only rule has been improvisation.

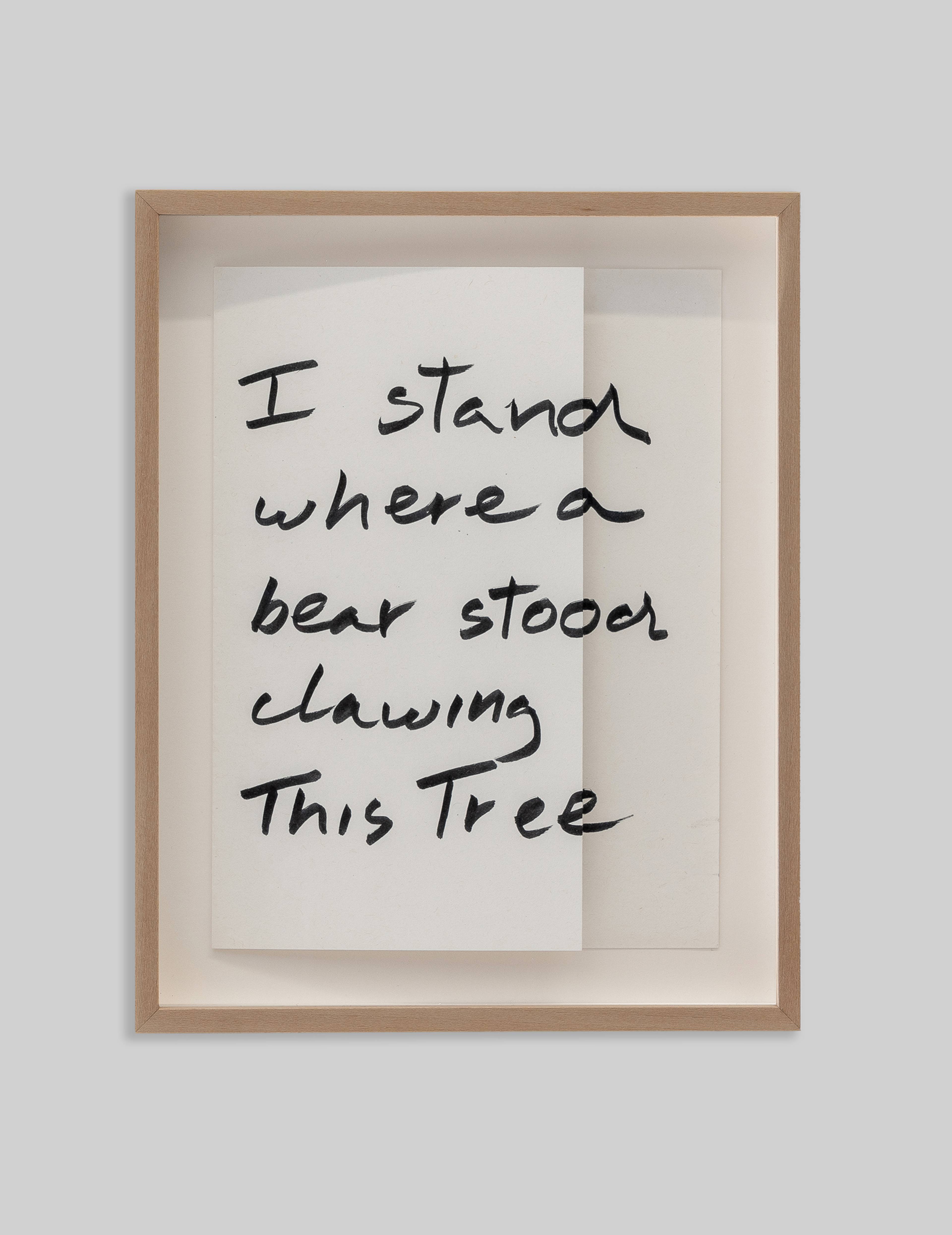

Simone Forti, “Framing Movement,” Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan

Luca Lo Pinto: Dear Simone, the last time we met, you told me that you feel like a small bird, with two stones instead of legs. As you have become very limited in your movements, how have you experienced the transition in your poetry from your body to language?

Simone Forti: Parkinson’s disease is different for each person. These days, I feel pretty strong. True, I can’t even walk, but I make good use of my arms and do move quite a bit, lifting my laptop and the books that I’ve gathered over the years. Just now, I’m reading Here Am I-Where Are You [1991], a detailed study by naturalist Konrad Lorenz of Greylag Geese. How they live among each other, or, more precisely, how they move in each of their different actions, such as flying into the wind or shoulder-fighting.

I read a lot of poetry during the lockdown, such as Charles Olson’s Mayan Letters [1953], where I found a familiar appreciation for the physical, whether in a crowded bus in Mexico or in the literal earth at an archaeological dig. I also exchanged writings with my pen pal, the artist Barnett Cohen. We went on to do three readings together, and my New Book [2024] grew out of that exchange.

LLP: It’s a new text composed of three of your previous poems, slightly edited. What’s the difference between expressing a feeling or a thought with the movement of the body and doing it through words?

SF: I tend to open a new path of work when I have a need that’s almost physical, and when I see some work that seems to fill that need. After four years of studies in focused improvisation with choreographer Anna Halprin, I came across images of Gutai artist Saburo Murakami performing his piece Passing Through [1956]. He went plunging through a series of sheets of paper attached to wooden frames placed one in front of the other.

Shortly thereafter, I made Huddle [1961]. At first, I used it in my movement workshops as a tool to get people used to touching and being touched or to using physical strength together, as if being of one mind with the other workshop participants. As I stood back and watched them move, though, I was struck by the beauty of the form that was created and the importance of its inspired placement in the available space.

One recent movement experience I had was of falling and not being able to get up off the carpet. I tried with all my might for about half an hour before giving up and calling for a nurse to come help me up. Arriving briefly to my feet, I felt red cheeked and full of energy.

LLP: Around the world, we are observing tremendous numbers of people forced to flee their homelands in order to survive. As someone who fled the place of their birth – Italy, where the Racial Laws promulgated under Mussolini in 1938 stripped Jews of their citizenship and their livelihoods – how do you make emotional sense of this multitude of bodies moving across the earth?

SF: The impressions I live with affect me regardless of how true or false they are. One book I read during the lockdown is Thucydides’s History of the Peloponnesian War (c. late 5th century BCE). I learned that, of the many city states around the Mediterranean Sea, some were democratic, with orators, and lived pretty modestly; others, with empires, were rich and powerful from the taxes they collected in exchange for giving protection. There were constant tensions and shifting alliances, as colonies tried to break away from their oppressors, along with a floating population of soldiers. But it feels different reading about massacres that happened thousands of years ago, in lands with exotic names.

LLP: Today, more and more artists are making art whose ultimate intents are not objects, but non-objects – moving images, music, movement – raising the problem of how they should be collected, preserved, and exhibited. With your own work, which is improvisational and thus very personal, you don’t give instructions, but instead try to convey the right attitude to the performers who will execute your pieces. How do you think about transmitting a spirit rather than a defined object or score?

SF: I see that art which leaves no physical object is a problem for a museum. How to display it, then, other than in the moment of its live presentation? As an artist, I am more concerned with how the work will continue to be active in the discourse in its field. I have seen a renaissance of some of my work, to a great extent because museums have brought it back into play. MoMA has taken over the care of my “Dance Constructions” [1960–61], which don’t exist without being rebuilt. Onion Walk [1961], consisting of an onion ripening, shifts its weight, and, eventually falling, has been performed at the Getty in Los Angeles and displayed at the Salzburg Museum.

Over the years, I have done more teaching than performing. And yet, I see that my influence as an artist who works primarily with movement is still alive. A revolution in the dance field came with the proliferation of performance work and a turn in education, from the class format to the workshop process, with its emphases on exploration and on the creation of concepts that give direction. Improvisation really comes alive when the dancer works freely within a field of awareness.

___

Simone Forti’s New Book is published in English by NERO Editions.

“framing movement”

Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan

4 Oct – 23 Dec 2024