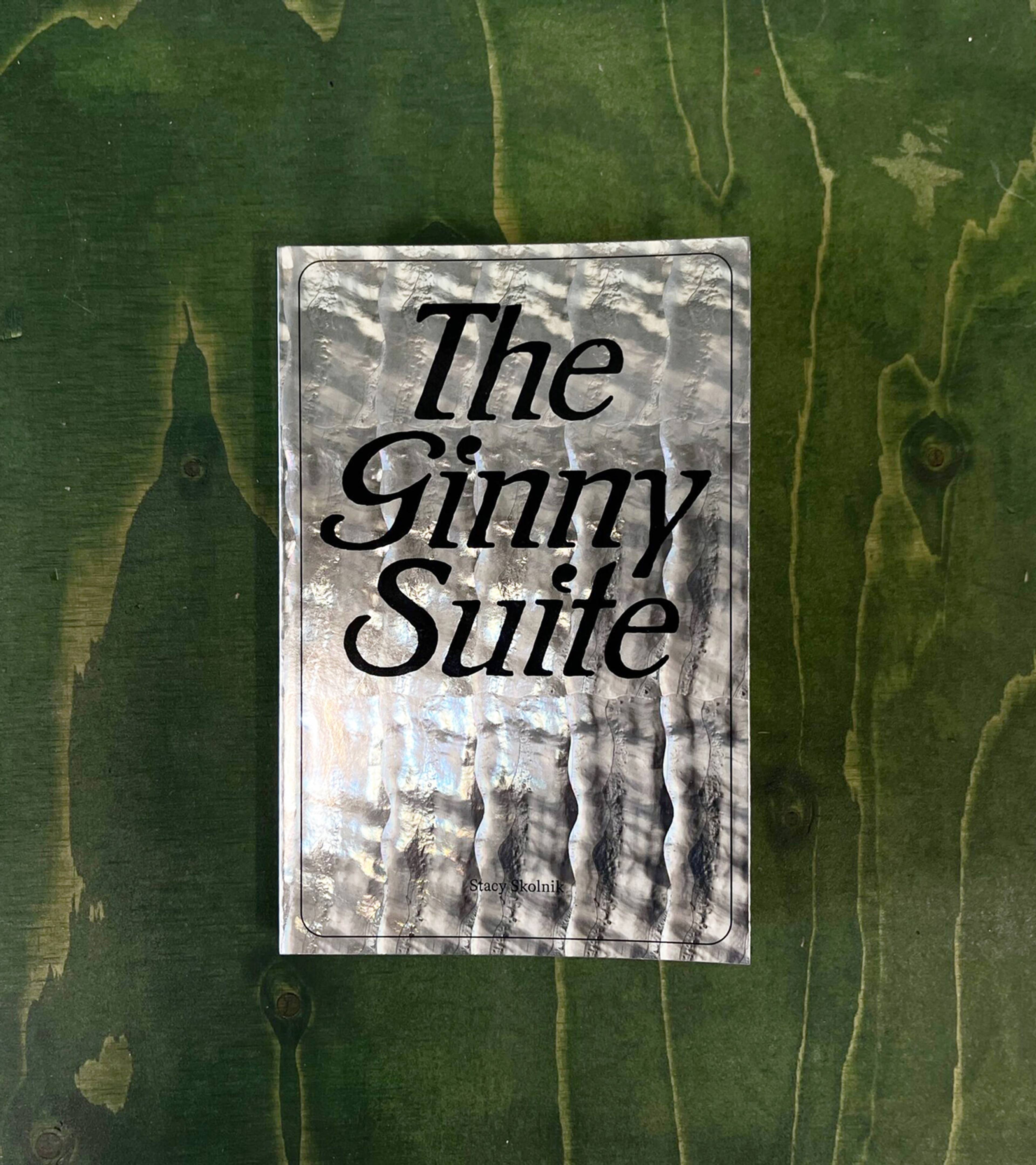

In Stacy Skolnik’s new book, The Ginny Suite (2024), poems, news stories, off-kilter pop-up ads, medical forms, and Instagram posts erupt from and build the narrative. The unnamed protagonist, a writer in New York City, tries to write on her phone in bars in the afternoon, or drifts around to nighttime assignations with nameless men, while in the world around her, an illness the press calls Sunnyvale syndrome seems to be targeting women, its symptoms aphasia and dissociation. The book explores intersections between sex, gender, writing, technology, and information in surprising, unsettling ways. The Ginny Suite is darkly funny, eerie, and horrifying in its depiction of a world just one or two degrees away from our own – a mirror world that one senses one might easily stumble into, just around a corner at 2am, down some weird Reddit thread, or through the door of a seedy bar.

Claire DeVoogd: You’ve written a really interesting book. In the first story in the book, “Degenerate Matter,” the narrator recounts a sexual encounter with a nameless man; they walk around the cold city with his arm “pressing down on her oppressively,” her body is a “sack of flesh” to be dragged around; he teases her, when she’s cold, that she’s “just a bitch in a leather skirt” – kissing him, she’s “running her nicotine tongue over his lips.” Later, we deduce that she’s cheating on her husband, habitually, something she makes no apologies for. That’s at odds with what we usually expect from books, because we often expect a likeable character. Were you conscious of that as you were writing it?

Stacy Skolnik: The book operates around ideas of repulsion. The protagonist’s primary emotional state is one of being repulsed by and distrustful of almost everything. As in real life, the socio-political climate in the book is insidious, it seeps into her body, it informs her desires, it influences her mental well-being. Her data and information are collected and then used to manipulate and mediate her experience of the world, to sell her products and ideas that she’s susceptible to buying into. This is an irony of contemporary life, that we are sold things at every turn that we are told we need, but we have to examine every product to make sure it’s not toxic. The most basic levels of consumption seem fraught with risk.

Poetry represents the desire to draw understanding from a disinterest in resolution.

CD: Repulsion makes a lot of sense as a countermeasure: a kind of swerving away or pushing back against the pressure to sell oneself, or one’s book. I find this converges with gendered dictums about women being “nice.”

SS: I'm drawn to the process of figuring out how to make containers for concepts in formats atypical of the mode I’m working in. I’m less interested in achieving an ideal than I am in disproving to myself the idea that there’s nothing new under the sun. What’s the point of making art, if just to recreate what’s already been done? It feels good to be bad.

CD: The protagonist is a poet, and poems are worked into many of the stories – what did you draw from poetry when writing this novel?

SS: Poetry represents the desire to draw understanding from a disinterest in resolution. It communicates through its ungraspability, its codedness, its internal logics. A lot of my work thus far has been about taking language from various sources, finding and extracting the poetry from cold or hostile social-textual environments. And even though it’s a novel, I’d say the book almost operates more like a poetry collection, in that it’s bound by connected motifs, more so than your standard notions of arc.

The whole book is on the quest to perfect the imperfect body, an analog to “woman” as the impossible ideal.

CD: Let’s talk about gender. Sitting with a body while it’s sick or dying is historically women’s work. Women have so often been the people who have documented sickness, like Audre Lorde [in The Cancer Journals, 1980] or Anne Boyer [in The Undying, 2019]. Sickness and gender are often joined in The Ginny Suite. Early in the book, the narrator recalls her childhood desire to have an illness, something that would generate sympathy from her peers and caretakers; she claims that this growth “would not do, as I wanted my self-selected condition to be something that would make me not grotesque and exposed, but beautiful and mysterious, fragile and feminine.” It’s because of this growth that the socio-political, in the form of “Sunnyvale syndrome,” and the narrator’s personal life might converge – her condition, “grotesque and exposed,” is the wrong kind of sickness for a woman. Sunnyvale is like a “toxic femininity,” the symptoms of which, we learn early in the book, are loss of language and dissociation from self. Be careful what you wish for. Do you have thoughts on this?

SS: There's something to be said about the condition of femaleness, and gender generally, as an affliction. The performance of gender in the book manifests as malfunction, whether through Ginny’s glitching pronouns or the exertion of violence by men to fulfill roles they think they have to adhere to. Even though The Ginny Suite might be read as a feminist work, I feel like it’s also, somehow, a post-gender novel.

CD: I don’t read The Ginny Suite as a feminist book, necessarily. I read it more as a queer theoretical book. We’ve talked before about the sonic and semantic slippage between gender and genre; that’s at play in this text, as the forms and genres it’s composed of jar against each other – medical reports, sci fi, autofiction, poems – a composition the impurities of which mark the text as pariah: It’s not easy to ID, except by its difference. It also both documents and strays from the norms of gender and sexuality. This is heightened by the final section, “Pathology Report,” which is accompanied by a patient ID number. However, rather than medical lab results, the section comprises a Google search history in which the research that went into building and writing the book can be seen, as if The Ginny Suite is representative of the “pathological” body itself; a “sample” of its narrator/writer’s aberrantly gendered, aberrantly sick body.

SS: The fact that the protagonist is only called “she” and “her” and “I” is a parodic indicator of the overemphasis on what language and speech acts prescribe onto her personhood. In terms of illness, I think, to be prescriptively gendered is a kind of bad diagnosis. There are a lot of moments of anxiety circulating around the narrator’s domestic tasks like cooking and cleaning, a lot of bathroom scenes where she’s cleaning her body instead of the grout. The sickness component both comes from this critique of gender as well as an awareness of aging out of girlhood. The whole book is on the quest to perfect the imperfect body, an analog to “woman” as the impossible ideal. The protagonist’s imperfections are both physical, like her less-than-perky tits, and behavioral, like her over-consumption of alcohol and drugs, her overactive sex drive, quote unquote.

Portrait of Stacy Skolnik

CD: In the chapter/story “Interlude,” there’s a scene where gender and class and illness are suddenly brought into conflict. A possibly mentally ill or homeless man bumps or hits a woman, it’s not clear which, and the men on the train respond with this show of aggression and force against the man, repeating, like a mantra, or a formula, “No man should ever, ever, ever hit a woman.” There’s an intimation that they, too, might hit other women in private, however. And they are perfectly willing – proud, even - to exert violence against this very vulnerable man. For me, the scene illustrates the conditioning of the performance of gender, in which the actors are running through a prescribed script, which, because it’s so normalized, they believe to be a logical machine, and the reader can see the script breaking down.

You see the fracturing in some of the sex scenes as well. There’s the guy who keeps slapping her ass harder and harder: She says stop, but he doesn't, and afterwards, he says that he thought she said she liked it.

SS: Not to mention the perversity of wanting a little bit of that violence; it mutates into desire. She says, at one point, “I like to pretend to be unconscious, defenseless, a dream away from dead.” It makes me think of a question you posed once about the book: Can those who delight in their own domination ever really be dominated?

Writing, I think, is a potential avenue through which one can avoid being infected, or “turned.” Any creative act, really, is a pathway toward liberating one’s self from prescribed diagnoses or pre-formulated narratives

CD: The Ginny Suite reminds me of Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl [2012] by the French anarchist collective Tiqqun. In Ariana Reines’s translator’s note to the English edition, she writes that she became physically ill from it, she had trouble digesting food while she was translating it; a reaction against the way the book deploys gender. She suggests that it might be read medically, as a diagnosis of an illness. You can read The Ginny Suite as similarly diagnostic, an inventory of gender and its symptoms. It’s a bit sickness-inducing.

SS: One is left to wonder at the end of the book if the protagonist has been affected by Sunnyvale syndrome. Has she or has she not been turned into a victim? And why or why not? Writing, I think, is a potential avenue through which one can avoid being infected, or “turned.” Any creative act, really, is a pathway toward liberating one’s self from prescribed diagnoses or pre-formulated narratives, toward knowing one’s self better and making one’s self known.

To go back to your original question, I think her constant self-deprecation is an act of self-preservation; it prevents her from being wanted or maybe even liked, and therefore separates and possibly protects her from other people.

CD: She’s using her pathologies to self-quarantine.

SS: One of the things that characters or readers might find repellent about her is that she’s doing womanhood wrong. Her persona is actually probably quite familiar to us, but from novels by Ernest Hemingway or Raymond Carver, hyper-masculine stories about hyper-masculine men.

CD: Yeah, she’s at strip clubs drinking in the afternoon.

SS: She’s fucking at work, cheating on her husband.

CD: Do you think she’s vulnerable, and in what ways?

SS: The question of vulnerability and consent are tied together in the book and are woven throughout all of the stories.

CD: I recently wrote a line in a poem, “I cannot consent to you reading me.” Verbal consent fails at the point where language becomes public.

SS: Yeah, or where language becomes shared. Because verbal consent can fail in private, too; what we say isn’t always what we mean, or what we mean isn’t always understood. But that friction, especially in writing, is what’s exciting. Once you put something out into the world, it’s not yours anymore; you can’t control it. I would so much rather someone have a visceral reaction of hatred to this book than to have a completely blasé feeling of ambivalence toward it. Maybe every artist feels that way. It's not just about getting a reaction. But the flaws, the parts that invite judgment, that expose the seams, that’s where risk happens. That’s where possibility happens.

___

Stacy Skolnik’s novel The Ginny Suite (2024) is available for purchase from Montez Press.