Plate 44 of Francesco Goya’s Disasters of War (1810) depicts a caravan of people fleeing what we suppose are Napoleonic troops ripping through Spain. A terrified woman in the foreground, baby slung over her shoulder, pulls a second young child away. Two men beside her make haste, pointing to the out-of-frame danger to which we viewers are not privy. Goya’s inscription reads Yo lo vi (I saw it).

Terry Atkinson (b. 1939) has developed a practice over the past sixty years, which is as rigorous as it is restless in asking: what persists in a claim as simple as having seen something? What is involved in writing something like “I saw it” after depicting “it”? And what kind of thought about transmissibility must have already taken place in order to do so? If the claim “I saw it” triangulates artist, subject, and audience into a geometry of complicity, Terry’s body of works strips its vectors’ lubricating appeals to art’s exception from norms of communication, surgically dissecting unquestioned transpositions of “knowing” and “looking” on the way. This may sound awfully harsh. It is a good thing then that Terry has a terribly good sense of humor. At eighty-five he is as sharp, unflaggingly curious, and unguardedly generous as even his earliest works indicate.

Sam Lewitt: I first encountered your work in a book. While it’s unremarkable or at least not unusual that I arrived at your work through a catalogue, it’s worth noting, since having the reproduction of the work next to your often incredible titles seemed to me, at the time, to test the limits of descriptive incommensurability. To take an example almost at random, I’m thinking of your mixed media WWI works from the mid 1970s to early 80s, with titles such as:

Botched-up art work depicting intra sexual, intra working class sadistic act under the Emergency Powers Act, the two acts undertaken in the service of imperialism.

It might seem perverse to stick to questions of how certain media facilitate relations between text and image when confronting the subject matter of a work like this – attempting to represent the psycho-social carnage of Western imperialism. But it is surely important (not least for me), indicated by your frequent inclusion of self-doubt, rhetorical parroting, misfires of speech, such as this title’s self-reference as a “botched-up art work.”

Terry Atkinson, Botched-up art work depicting intra sexual, intra working, class sadistic act under the Emergency Power Act, the two acts undertaken in the service of imperialism, 1981. Courtesy: The artist; Galleria l'Elefante; Fondazione Imago Mundi

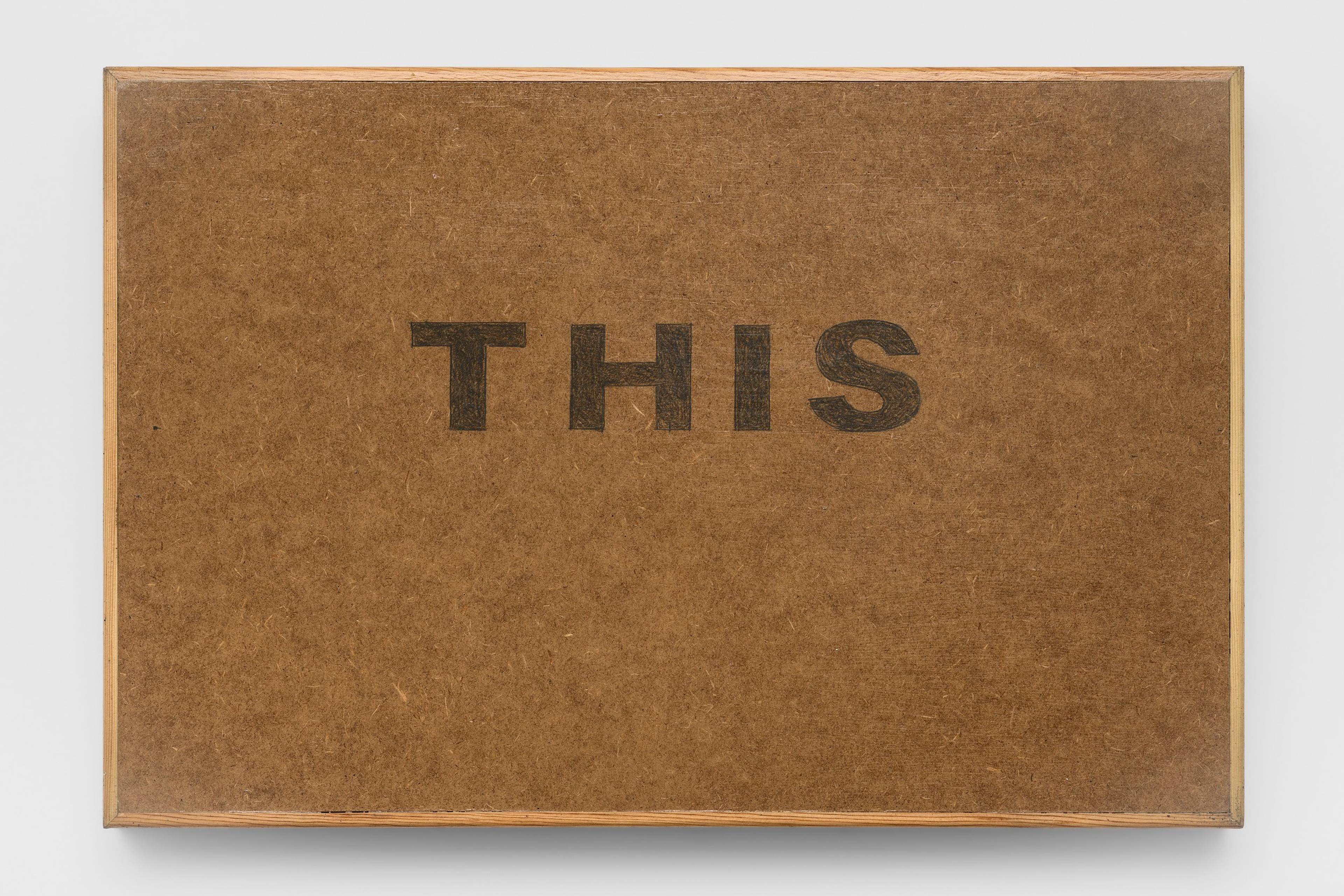

Terry Atkinson, This, 1996, pencil on board, 36.8 x 55.2 cm

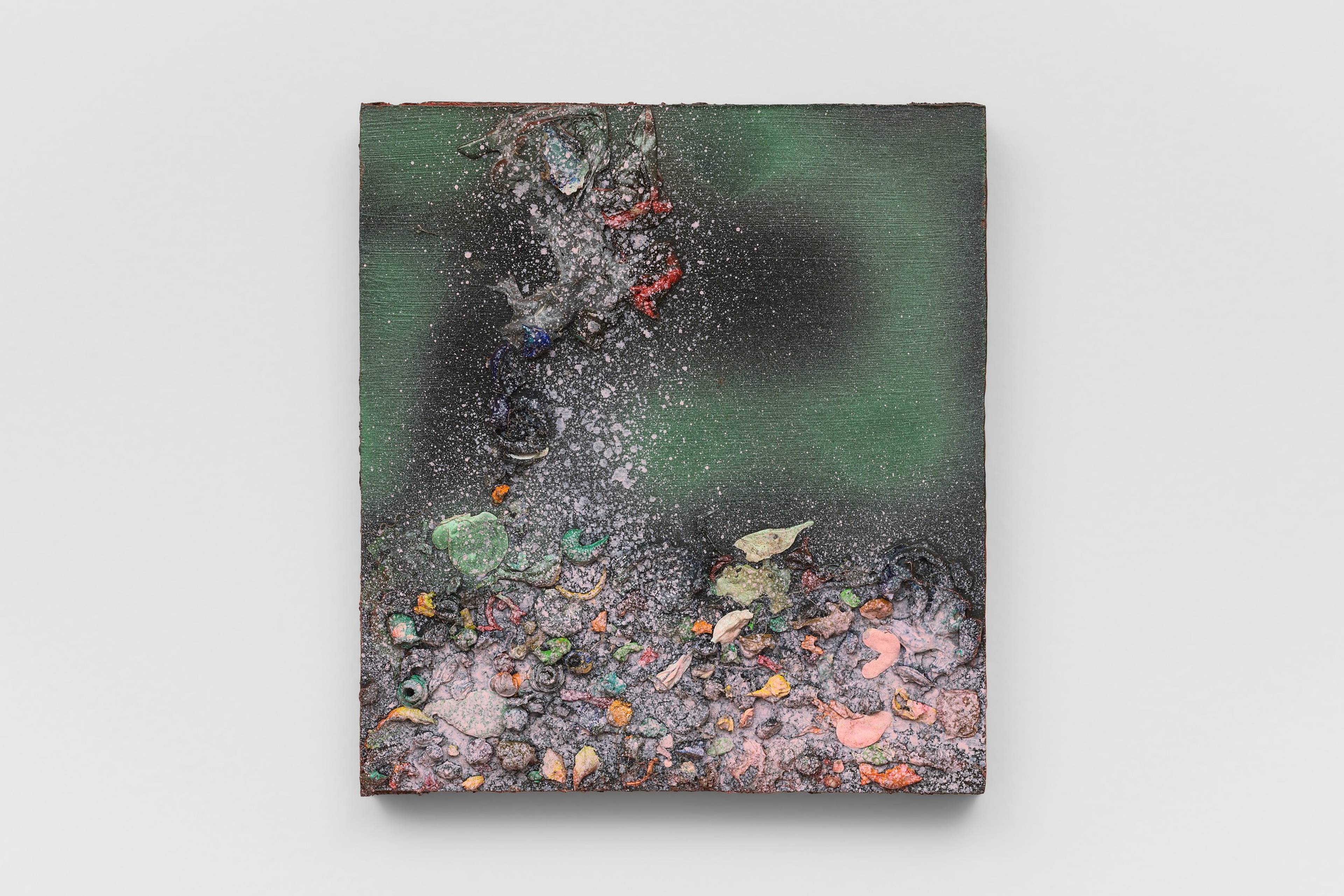

Terry Atkinson, Map of Paint Island 3, 1986, mixed media, 21.5 x 20 cm

Terry Atkinson: It seems often that long texts, sometimes loaded with specifics, notations, lists, diagrams, etc. are troublesome for the art community’s presuppositions concerning the sites of production, display, and distribution of artworks. More often than not, texts/titles are treated near to insignificant in the act of looking, where looking is separated from the act of thinking, which is a kind of champion incontrovertible buttress of the promotion of the idea of the “purely visual.”

According to the most determined advocates of the “purely visual,” texts are oppressors of democracy, they give directions as to both how to look and how to think. At the center of this resistance is some hardly formed inchoate notion that does not just separate looking from thinking, but sees thinking as counter-productive to this supreme act – applied to both producer and viewer – polluted by slippery wordsmiths. Always hovering around this mythology, but at times penetrating deeply into forming it, is a notion of a fundamental self – untouched by learning and out of reach of conscious thought – which relies solely on some such thing as “intuition.” And this, in turn, presupposes that intuition can be cleaved clear of cognition.

The confusion that freedom equals non-interference has one of its most manifest realizations in the argument against some such as Thatcher’s “nanny state”: the less intervention by the government the better. It became a near definition of democracy by these ideological warriors and their administrations.

Against this steadily right-moving, post-WW2 foreground, especially from the 80s onwards, de-centering the pictorial as focus and setting up alternative structures of interpretation and translation seemed to me to demand theoretical clarity and dogged resolve. The long texts I frequently attached to my pictorial resources were in themselves attempts to protest the hegemony of the visual. Sometimes the texts, not least the long ones, contained historical reminders and remainders that the visual had never enjoyed the “purity” that its 20th-century champions alleged it to have. Both some of William Turner’s titles and William Blake’s explicit embedding of text in the picture surface were examples I took as refulgent precedents.

I argue that the art world has been strongly conditioned to hold that looking is primary to thinking. Is the alleged primacy granted to something, let’s call it “looking,” such that another thing, let’s call it “the pleasure of looking” is taken as a given?

SL: This assumption that the agency of the viewer is more “democratically” capable of self-legislation in the absence of textual supplement was especially strong in one strand of American 20th-century modernism. Your work with Art & Language was instrumental in displacing this in the late 1960s. Both Jackson Pollock and Donald Judd, for example, abjured titling in an apparent effort to reduce the system of representation to the work’s sensorial and spatial objectivity. This in some sense empowered the critic as the arbiter of judgment and therefore speech. Can you elaborate a bit more on what led you to this polemic against the cleavage between critical discourse and visual experience?

TA: For the “pure visualites,” maybe their most consistent and coherent line would be to stick rigidly to Wittgenstein’s aphorism “What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.” It is, or rather it seems to me, that not to use any words when referring to art is difficult, how then would we refer at all? I guess we could count somebody silently and mutely pointing to, say, a painting as a referring act, but it is a silent act, and the thought of it articulating a sophisticated inquiry into the meaning of the work and/or the intention of the artist is pretty hard to figure out.

Snuggled tight up against the notion of the “purely visual” is the notion of a “purely visual language.” I remember coming up against this notion in my very earliest days in a British art school in 1958, a tutor I had at that time repeatedly and insistently kept referring to some such as “Braque’s visual language.” I puzzled over this for several months since I struggled to comprehend what it might mean. I knew enough about the concept of language to realize that the presence of grammatical rules was a necessary component for something to count as a language. Eight or nine years later, in the earliest days before the official forming of Art & Language, whilst working closely with fellow artist Michael Baldwin, we came across Wittgenstein’s inquiry in Philosophical Investigation (1953) into The Private Language Argument (to put it crudely, it questions the coherence of the claim that there can exist a language which is only understandable by a single individual.) This confirmed for me that the notion of a “visual language” was meaningless. To seriously condense the matter to its simplest puzzle: What are the grammatical rules of this (visual) language, how does the syntax and semantics of this (visual) language operate?

Another Wittgenstein quote is perhaps worth mentioning in this context. It’s a statement about a general condition of our life but can be applied specifically to the target of my remarks, what I am calling the mythology of the “purely visual”: “Nothing is so difficult as not deceiving oneself.”

During the early Art & Language days, Baldwin and myself were not infrequently accused of being “slippery wordsmiths” (or sentiments to that effect) in talks we gave at a number of British art schools in the late 60s–early 70s. One of the most memorable of these occasions was at Birmingham College of Art when one member of the painting faculty assailed us with threats of physical assault. Michael responded with confrontational wordsmithery and the aspiring assailant backed off – still in my mind a classic case of “jaw not war.”

Goya, Plate 44 from “The Disasters of War” (Los Desastres de la Guerra): I saw it (Yo lo vi), 1810, etching, drypoint, burin, 15.8 × 23.5 cm (plate)

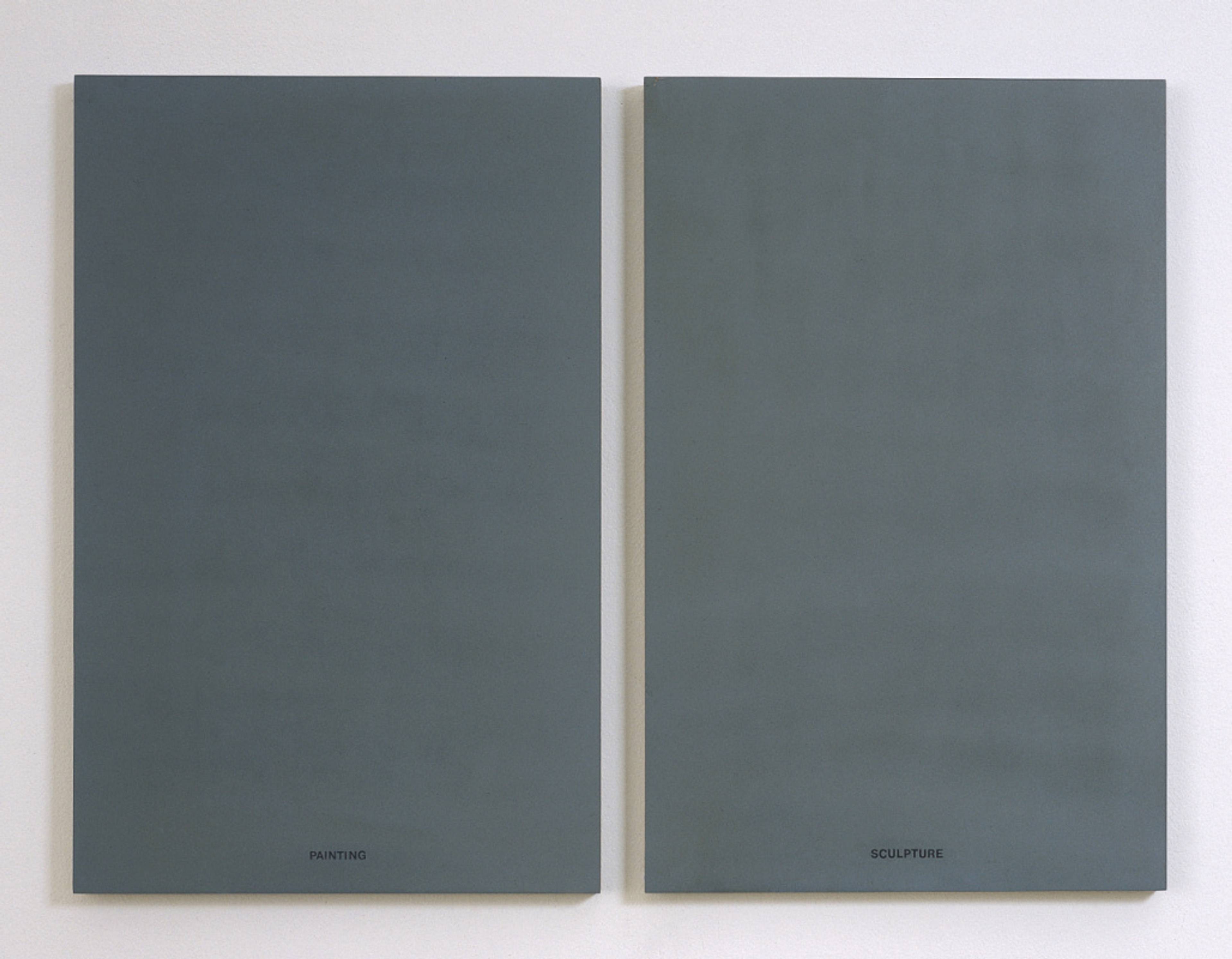

Art & Language, Painting and Sculpture, 1966–67/2005, plywood, wood, acrylic, 2-part, 73.2 x 37.6 x 3.7 cm each. Courtesy: ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe / Art & Language

SL: I’m very interested in the way the logical relations you unfold don’t cohere into a “therapeutic” account of language (as they do according to some for later Wittgenstein.) Text’s at turns problematic, supplementary, and compensatory function within the history of 20th-century artistic production – in view of all the presuppositions about the role of visuality you indicate – seem to me intensified in your work.

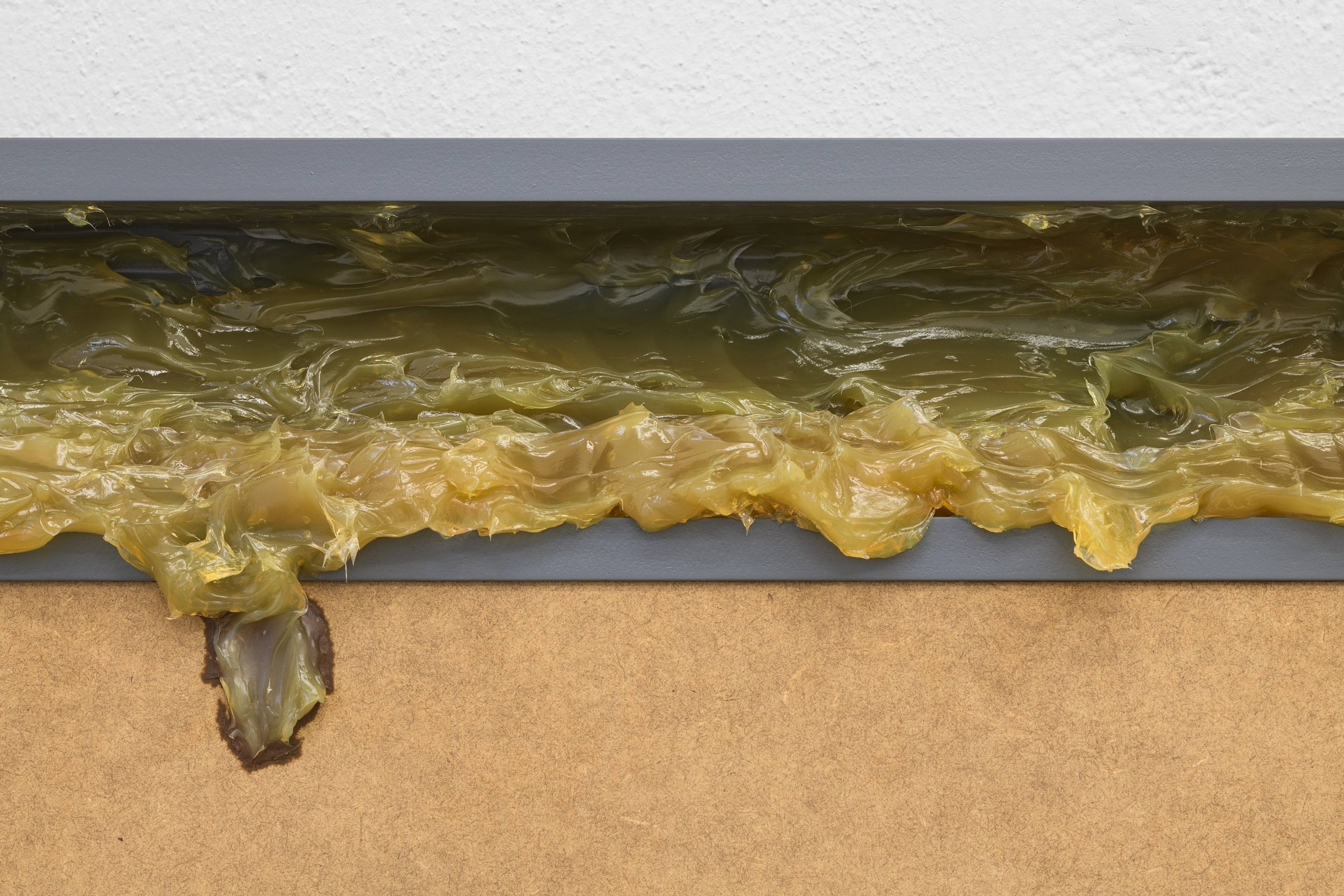

In other words, while the work directly addresses suppositions about what an artwork ought to offer, how the offer is made, and what its limits are, it doesn’t bring these problems to rest. You rather unleash a host of new problems generally suppressed by these suppositions. I think here about your Greasers, which were mostly conceived in the late 80s and early 90s. In these works you’ve essentially formatted – in some cases “composed” seems more accurate – wooden structures acting alternately as receptacles, frames, and troughs for certain quantities of petroleum grease. The first of many problems that these works seem to generate is the fundamental instability of their material components: becoming more or less fluid according to room temperature, potentially ruining walls and floors. You write: “Grease generates quite a lot of decorative and extraneous incident.” It also ignites in a firestorm of language and lists in your various texts about it. To quote from your 1988 title/text for the first of these works:

Using grease.

1) The material of the avant-garde greasers.

2) Grease – the new material.

3) Grease as a repository of the potentially oppositional. Chortle! (Be serious now! Grease is entering the portals of serious art histories of the social referent.)

4) Grease as a disaffirming material – will it ever dry? I don’t know, but I can find out. From Castrol for example. Castrol the art object consultants.

5) Grease is the perfect material for a successful art career.

6) Grease, the perfect material for the civilization of senior common room culture.

7) Grease is the perfect material for making copies.

Grease becomes something like a super-metaphor, into which is collapsed the whole field of aesthetic, market, and political relationships that move the material through your work.

Terry Atkinson, GREASE-FALL, 1990/2024, wood, varnish, grease, 97 x 150 x 24.5 cm

Terry Atkinson, GREASE-FALL, 1990/2024 (detail), wood, varnish, grease, 97 x 150 x 24.5 cm

TA: Grease in certain conditions is uncontrollable. This directly brings up the notion of accident: if art is held to be a case of the artist’s control over the materials, that control is a measure of the fulfillment of her/his intentions. This relation between accident and control and intention was at the center of my cognitive two-year-long approach to using grease in 1987. In what sense can an artist realize their intention if the material the artist uses is ipso facto uncontrollable? Sam, you and I might frame the matter of the dissolution of the problem of intentionality considering that “one might want to begin by searching for connections between the now commonplace expansion and homogenization of material resources and media [admitted into artworks] to fundamental characteristics of the crises of capitalism that serve as their historical backdrop,” as you wrote in your 2013 essay Materials, Money, Crisis: Introductory Remarks and Questions.

I conceived of axel grease as “software” and the wooden structures that house it as “hardware” – therefore as crude automata. Grease as software gets even “softer-ware” you might say, when it turns to oil and oil has, in the twentieth century, been capitalism’s great grifter – the material resource that has, literally as well as metaphorically, kind of ghostly personified flows of capital, echoing you from that same text, echoing Marx’s dictum “Not an atom of matter enters into the objectivity of commodities as values …” The invention of the “petro-dollar” says a lot about Nixon’s haste to get off the gold standard, as the new liquid gold of, say, the Red Sea and Arabian Gulf became a main factor in the outcome of the Cold War.

SL: There might be a more pragmatic way of discussing the issue of how materials are admitted into artworks, but certainly not a more useful one to my mind. It is useful on one very basic level for integrating the work that artists do as one more material (one more layer of grease?) that goes into whatever is produced as an artwork, rather than a source of what you call here “control.” What are we to make of the weird idealized category of the viewer in all of this? What does it entail even if we agree to dispose of “pure visuality”?

TA: Perhaps ask “What can viewing entail” rather than “What does viewing entail.” The former seems less dogmatic. Answer, perhaps “entertainment,” perhaps “being of interest,” perhaps “engagement.” All these functions (many, many of them – as many as there are transitive verbs) may constitute the content of a viewing event. To be “entertained” may also come within the notion of “engaging” and “being of interest” for example. In contrast being “repulsed” may constitute “being of interest,” but we might hesitate a bit if we characterized the repulsive event as entertaining. We are involved here in a seemingly endless dance with both the possible overlapping meanings of these transitive verbs and the possible clear distinctions between their meanings.

SL: Ok. I’ll bite. There are the transitive verbs and there are corresponding judgments on particular experiences (in your view these are linguistic on every level). I think, actually, much of contemporary culture is happy not to hesitate over entertainment – or at least stimulation – by what is essentially repulsive. But there’s a subjective dimension to this. We’d have to account for the judgments of who is repulsed and entertained by what, no?

TA: The question is how predictable can reception be made. Assuming the conditioning is strong enough, reception can be extremely predictable. I argue that the art world (for want of a better name) has been strongly conditioned to hold that looking is primary to thinking. Not in the obvious sense of physical sequence, but in the sense of separating looking from thinking. Is the alleged primacy granted to something, let’s call it “looking,” such that another thing, let’s call it “the pleasure of looking” is taken as a given?

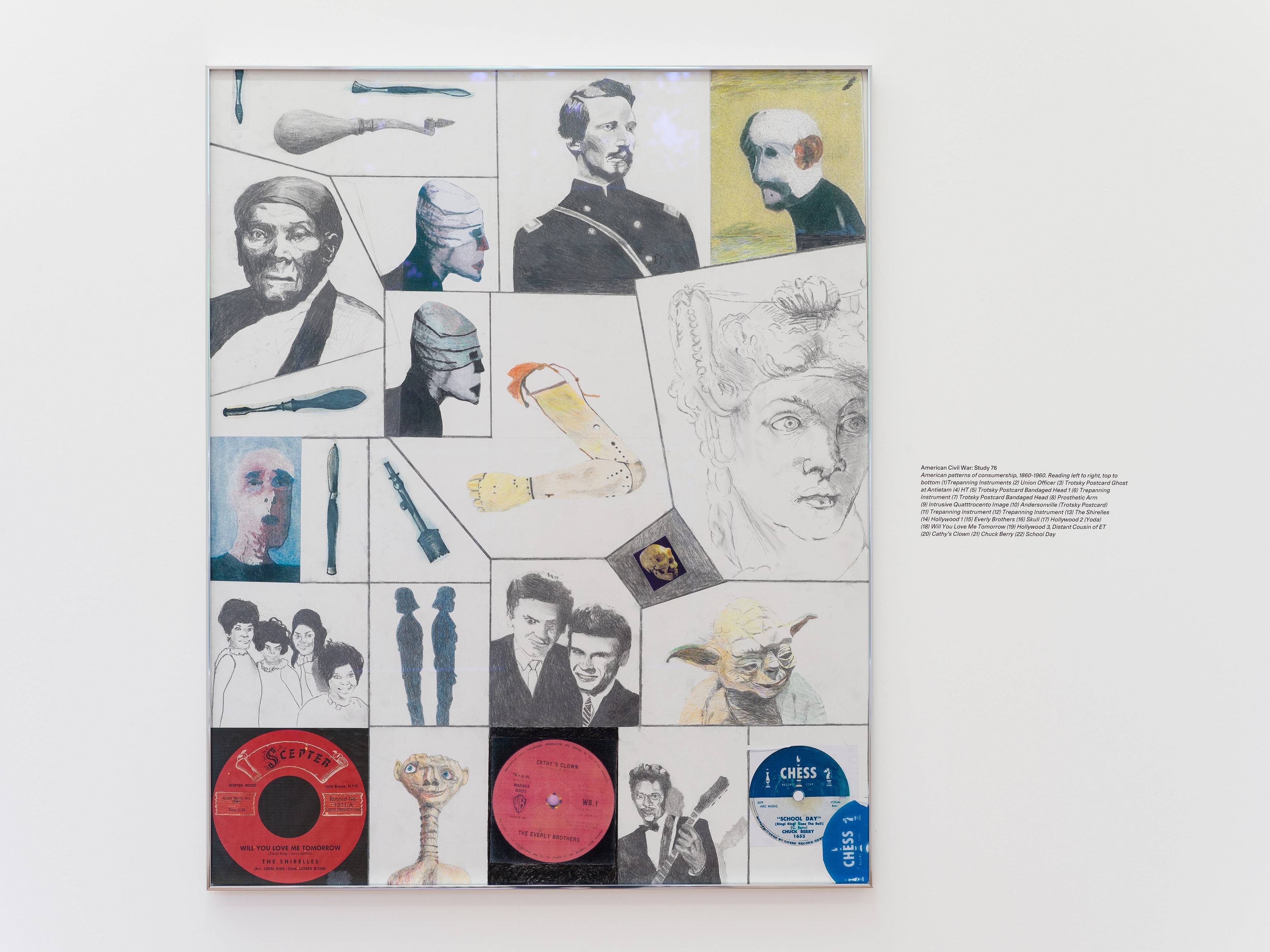

Terry Atkinson, American Civil War: Study 76. American patterns of consumer- ship, 1860-1960. Reading left to right, top to bottom (1)Trepanning Instruments (2) Union Officer (3) Trotsky Postcard Ghost at Antietam (4) HT (5) Trotsky Postcard Bandaged Head 1 (6) Trepanning Instrument (7) Trotsky Postcard Bandaged Head (8) Prosthetic Arm (9) Intrusive Quatttrocento Image (10) Andersonville (Trotsky Postcard) (11) Trepanning Instrument (12) Trepanning Instrument (13) The Shirelles (14) Hollywood 1 (15) Everly Brothers (16) Skull (17) Holly- wood 2 (Yoda) (18) Will You Love Me Tomorrow (19) Holly- wood 3, Distant Cousin of ET (20) Cathy’s Clown (21) Chuck Berry (22) School Day, 2020. Pencil, colored pencil, pastel and collage on paper, 101 x 81.8 cm

"Terry Atkinson: The Books are Very Nearly Cooked,” Schiefe Zähne, Berlin, 2024. Photo: Julian Blum

“Terry Atkinson: The Books are Very Nearly Cooked,” Schiefe Zähne, Berlin, 2024. Photo: Julian Blum

SL: I’ve certainly taken a great deal of pleasure in looking and thinking about your more recent “American Civil War” series (2018–). These colored pencil drawings are made up of blasted grids containing awkward reproductions of images drawn from various archival, televisual, and online sources. These images are as often related to the work’s eponymous subject as to the Russian Civil War, mid-century modernism, the American pop culture you grew up with, and contemporary media images. I think of you, Terry, as a kind of furious stenographer of historical fragments, which very clearly distances the mix of signs from satisfying itself with the facile shock of simply putting Yoda soaring above Union Soldiers. There is a subjective specificity – and an acid humor – to these little fragmented fields of images, from E.T., 19th century prosthetic limbs, Trotsky ephemera, and pictures of “Goya saying hello,” as one of your titles notes. These fragments all relate to your historical experience as a practicing artist and social individual, but they somehow blast the merely personal out of the continuity which is held together by that experience. Can you speak a bit to this work?

TA: The “American Civil War” works are often multi-titled since each image making up the work has some kind of title attached to it so, as a conglomerate, each makes up a list of many. Dividing the picture up into squares, rectangles, triangles etc. is a device I’ve used repeatedly in drawings and paintings since ’62. The full array of titles matching the full array of images I guess might be treated as a text, where text is treated as an expansive, and maybe more specific, than a title – certainly more expansive, for example, than a title such as Untitled or No 1.

I guess I’m sort of pleased that you derived pleasure from looking and thinking about the “American Civil War” works. I can’t argue with that kind of claim since to do so would be a bit like you exclaiming “I like strawberries” and me responding with “No you don’t.” Enjoying is notoriously subjective. Having just seen you wolf down a whole bowlful of strawberries I can take that as a strong sign you derive pleasure from eating strawberries. There is not a means of persuading a really determined solipsist to think otherwise. I have come across quite a number of determined and dogmatic solipsist painting students throughout my years of fine art studio teaching. Some such as “Because I like it” was sufficient for them to continue. The most determined one was, in a direct sense, the most consistent – she refused to talk at all. Studio teaching does seem to rely on talking, the most common and conventional intersubjective exchange – this is not insignificant. There seems to me to be little cognitive reward in attempting a conversational exchange with a dogmatic and behaviorally consistent solipsist. One lesson I drew from this was that a person does not need to know that he/she is a dogmatic solipsist to be one.