“I have never met On Kawara, nor do I know what he looks like. But from the body of work he offers I can see a man of great care, intellect and concentration. To the conservator’s eye, the Today series go far beyond the conceptual gesture of writing dates on a stretched canvas and putting it in a cardboard box. They represent an artist who – with the utmost attention and experience – chooses the finest materials, custom-made frames, first-quality Belgian canvas and the finest acrylic paint available.

To achieve a lively, dark – but in no way dull – saturated colour for the background, he starts with a layer of reddish brown, adding another layer of burnt umber, and another one of natural umber with a hint of dark blue. Finally, after four or five layers, this colour turns into a deep, profound, indefinable darkness. This technique of successive layers is also used for the red and blue Today series paintings.

All figures are created without reference to existing typography. Each and every letter and cipher is measured and put into place with ruler and pencil; in some parts traces of pencil marks show the corner-position of the type. This, however, can only be noticed under the microscope. The figures are executed with white paint, applied with a fine brush. The flow of the brushstrokes shows that the artist has painted all the figures freehand, occasionally correcting uneven outlines with the dark colour of the background.

To me, Kawara is a master of Calligraphy, a man of belief and, of course, one of the great artists of our time.”

– Christian Scheidemann in On Kawara (2002)

On Kawara, Technical study for Date Painting, 1990. © Christian Scheidemann

I do not remember when my friendship with the art conservator Christian Scheidemann began, but I do remember the first time he made an impression on me. It was with this short text he wrote for Phaidon’s 2002 monograph of On Kawara, with whom I was working at the time. Because of the artist’s lifelong refusal to grant interviews, the monograph featured a tribute section in which Kawara invited thirty individuals to contribute a statement on him – creating an indirect portrait. Among the contributors were artists, poets, critics, curators, scholars, and one conservator – Christian. I was struck by how he was able to capture Kawara’s essence so perceptively without having met him. The text was as much a portrait of the artist as it was a self-portrait of Christian. In it, I saw in him what he saw in Kawara: “a man of great care, intellect and concentration.”

This was back in 2002. That same year, Christian moved from Hamburg to New York and founded Contemporary Conservation – a studio with a unique focus on contemporary art made from non-traditional materials. He grew up in Bonn, where he studied the conservation of medieval paintings and polychrome sculptures as well as art history. He spoke of his first assignment as a trainee conservator – a Virgin Mary sculpture from 1520 – in a 2009 New Yorker profile: “Once, her coat was painted blue, because she was the royal mother. And then it was painted white, because she was the innocent Virgin, and then it was gilded. And what I found interesting was how the color changed the significance of the work.” In 1984, he left his position as conservator at the Kunsthalle Hamburg and opened his own conservation practice, specializing in modern and contemporary art. Around the same time, he also opened and ran a short-lived gallery with a few friends.

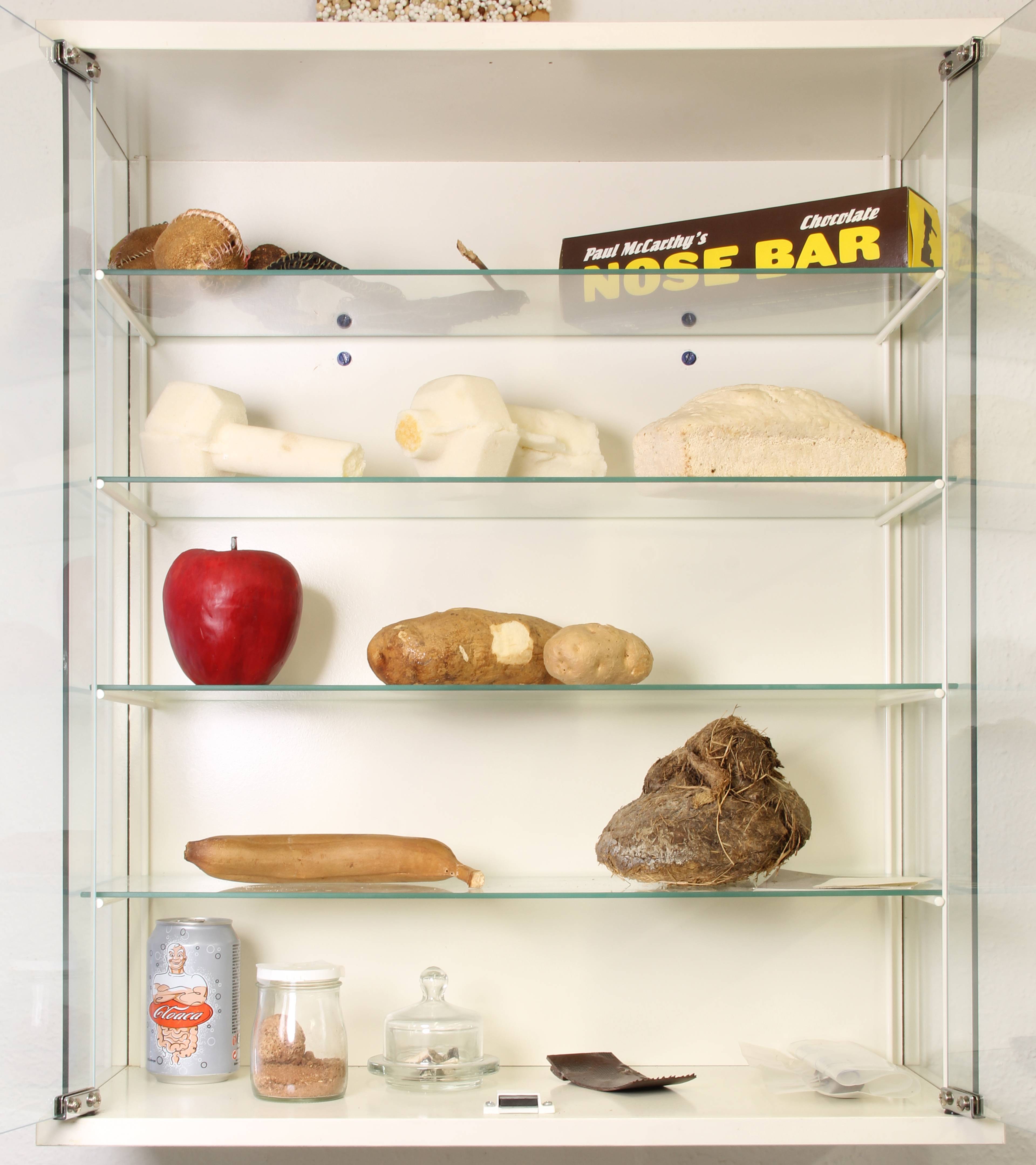

Today, Christian is a leading conservator of contemporary art and the first one in his field to have built his expertise on art made from non-traditional materials. Elephant dung, bananas, potatoes, pound cake, chocolate, cheese, bread, dust, blood, liverwurst, latex, soil, chewing gum, petroleum jelly, and human hair are just some of the challenging materials he has worked with. He even once gave a lecture called “The Significance of Dirt, Dust, and Bird Droppings in Contemporary Art.”

But it was a sink and a bag of donuts that changed his life.

In 1989, Christian found his true calling thanks to an accident. Shortly after the opening of curator Harald Szeemann’s exhibition “Einleuchten” (Making Sense) at the Deichtorhallen in Hamburg, a three-year-old boy mistook Robert Gober’s wall-mounted sink sculpture for a real ceramic sink and dangled from it. Both boy and sculpture fell to the floor – boy in shock and sink in pieces. Christian was flown to New York to discuss the repair with Gober. He recalls how proud he was when he was given a can of Benjamin Moore Dulamel alkyd white semi-gloss enamel paint. A quintessential medium in Gober’s oeuvre, the paint was applied by hand onto the surfaces of many of his sculptures – from sinks to doors to cribs to children’s beds to playpens to willow dog beds. (The artist even made a sculpture of the Benjamin Moore Dulamel paint can [Untitled, 2005–06].)

At the same meeting, Gober also asked Christian to help preserve Bag of Donuts (1989), a sculpture that he had recently shown at Paula Cooper Gallery in New York. The work consisted of a dozen real donuts inside a crumpled white paper bag made from hand-cut archival paper. To prevent the grease from staining the bag, Gober had coated them with Rhoplex (a toxic acrylic resin). Not only did the Rhoplex fail to stop the grease from staining the bag, it also landed a drunk and hungry visitor in the hospital after he took a bite of “donut” at the opening.

Christian rose to the challenge, degreasing the donuts with acetone in a low-pressure tank. However, they “lost weight” due to the loss of grease, thus compromising their structural integrity. Christian resolved this by soaking them in Paraloid B 72 (an acrylic resin) – a process known as plastination. The final touch? A sprinkle of cinnamon for aroma and appearance.

When Matthew Barney needed help with a big pound cake, Christian employed a similar plastination technique. The bigger challenge was its size – how to bake an over-sized pound cake without undercooking or over-baking it? A wire mesh construction was placed inside the cake to help it bake evenly.

Zoe Leonard, Strange Fruit, 1992–97, orange, banana, grapefruit, and lemon skins, thread, buttons, zippers, needles, wax, sinew, string, snaps, and hooks, 295 parts: dimensions variable. Installation view, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2022. © Philadelphia Museum of Art and Zoe Leonard. Courtesy: The Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photo: Timothy Tiebout

Zoe Leonard, Strange Fruit, 1992-97, detailed. © Philadelphia Museum of Art and Zoe Leonard. Courtesy: The Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photo: Timothy Tiebout.

Zoe Leonard sought his advice on preserving banana peels for her iconic work, Strange Fruit (For David) (1992–97) – an installation of 300 sewn fruit skins. The “fruitful” collaboration actually began with a misunderstanding, with Christian preserving a whole banana instead of just its peel at four to six weeks old. After two years of experiments and frequent exchange of “fruits and ideas” with the artist, Christian finally succeeded in arresting the peel’s decay at the near-perfect stage. That was also when Leonard made the final decision to embrace the inherent vice of her ephemeral material and let the work decay – a decision that both moved and delighted Christian. Preserving the piece would undermine the meaning and the integrity of the work – an homage to her friend David Wojnarowicz, who had died of AIDS, as well as a meditation on death, mourning, and the AIDS crisis. It is an interesting case of what Christian calls “the artist’s intention in the making” – since artists sometimes change their intentions as the work evolves or in retrospect, with some distance from the work.

I remember seeing Christian’s “first banana” in a display cabinet in his former studio, next to a piece of elephant dung. The dung was given to Christian by Chris Ofili – known for his use of the material in his early paintings and for offending former Mayor Rudy Giuliani with his controversial painting, The Holy Virgin Mary (1996),when it was shown at the Brooklyn Museum in 1999. Ofili uses the dung – considered sacred in many African cultures – to allude to his African heritage and to bring the African landscape into his work. To replace the elephant dung that had come loose, Christian obtained dung from a particular group of elephants from a London zoo – Mya, Dilberta, Layang Layang, Rara, Azizah, Money, and Lala – that Ofili calls his collaborators.

This spirit of collaboration makes me think of the Swiss-German artist and polymath Dieter Roth, known for his iconoclastic use of edible materials and for his engagement with the concept of decay. Referring to the insects that would eat away his chocolate sculptures, he once told Christian, “The worms and bugs in my pieces are my employees. You must not disturb them; they have to do their job like any one of us.”

Christian has always expressed the desire to devote more time to research and writing. Two years ago, he made the decision to step back from active conservation to focus on research, writing, and special consultation projects. As I am writing this, he is giving his last class of the semester as a visiting scholar at the University of Chicago. The theme today is “Variable and Time-based Media.” The course title? “Conserving Active Matter – Strategies in Conservation and Contemporary Art.”

To end my introduction on Christian, I would like to share a story that I heard at a symposium that Christian organized in 2018 called “Body of Work: Contemporary Artists’ Estates and Conservation.” The speaker, Loretta Würtenberger, an expert on artists’ estates, began her lecture by sharing a story on the first time she met Christian:

“Christian and I don’t only share a long-lasting friendship, we also share a godson – Constantin. Constantin is ten today. Christian and I met at his baptism, a little less than ten years ago. At the baptism, Christian was seated next to me. Not only was he the most charming neighbor at the table, he also offered a present to Constantin that impressed me very much. I am telling you the story because I think it says a lot about the generosity of Christian. He didn’t offer him a watch or a silver cup or other traditional things you would give a godchild for his baptism. His present was something very unusual. He gave him a language, meaning that he would support him – financially, but also in an immaterial sense – in learning a language. I thought that it was such a great, creative, and generous gift.”

This story touched me just as deeply as Christian’s words on On Kawara did two decades ago. In this immaterial gift, not only do I see “a man of great care, intellect and concentration,” but also one of great generosity, integrity, and ingenuity.

Christian Scheidemann in his studio with Zoe Leonard’s Strange Fruit. © Nina Quabeck

Eugenia Lai: What is the purpose of conservation, and what is the true nature of an artwork?

Christian Scheidemann: To begin with, conservation is many things: someone accidentally rubs with a handbag against a valuable, delicate monochrome painting in a collector’s home while kissing goodbye, or bumps into a sculpture while stepping back to look at a painting. Or, an art handler may carry a painting wearing gloves that are already soiled from opening the crate. Or, a cute puppy might chew on an early modular wooden structure by Sol LeWitt. Besides these more obvious accidental damages, there are those of a subtler nature: a pattern of cracks in the paint surface due to aging or use of poor materials; yellowing and cracking of latex and resin in sculptures; crystalizing of chocolate surfaces; or corrosion on metal surfaces.

The general approach in conservation is to gain as much knowledge as possible about the work before deciding on a treatment plan. What was the artist’s intention? How did the work look when it left the studio? How was it made? Who actually made it – the fabricator or the artist – or, was it bought “off-the-shelf?” What materials were used, and why? These and many more questions need to be explored. And then: is this “linear indentation” actually a scratch, or is it considered part of the work? By asking all these questions about the work’s history, meaning, and the making-of, the conservator gets an intimate view into the artist’s mind and into the life of the work. Not to mention the immense privilege and responsibility to be able to touch art!

The ultimate goal in our profession is to restore the integrity – or true nature – of an artwork. We want to ensure that the object we are looking at is actually the very artwork that came from the artist and reflects their intention. Conservation theorists have established a set of four standards of integrity: physical, aesthetic, historical and conceptual. While the physical integrity demands that the object consist of the very material, technology and components as the artist had conceived it – no losses, alterations or additions, the aesthetic integrity is supposed to convey the aesthetic sensation to the viewer. In addition, we want to see a work that we can trust to have been made at a particular time (historical), but also represents the intention and concept of the artist. An artwork, as we see it, is never just a visual or conceptual representation of an idea. It is always also a technical document of its time.

Conservation is much more than simply fixing things. The profession emerged in Europe only 150 years ago with the growing awareness and appreciation for art and artifacts from the past. Without connecting with the past, we wouldn’t know where we are in the present. Today, conservators are trained in science, art history, ethics, and technology, as well as in conservation methodology (a four-year program and fellowship).

I asked the artist if he thought these stains should be removed before the opening. “No – not at all. These are the fingerprints of Harry Houdini – they show how he had struggled to escape the sealed cabinet.”

EL: When I first brought up the idea of doing an interview, you suggested that we focus on the language of material. Should we start with dirt and dust, which you often say are underrated artistic mediums?

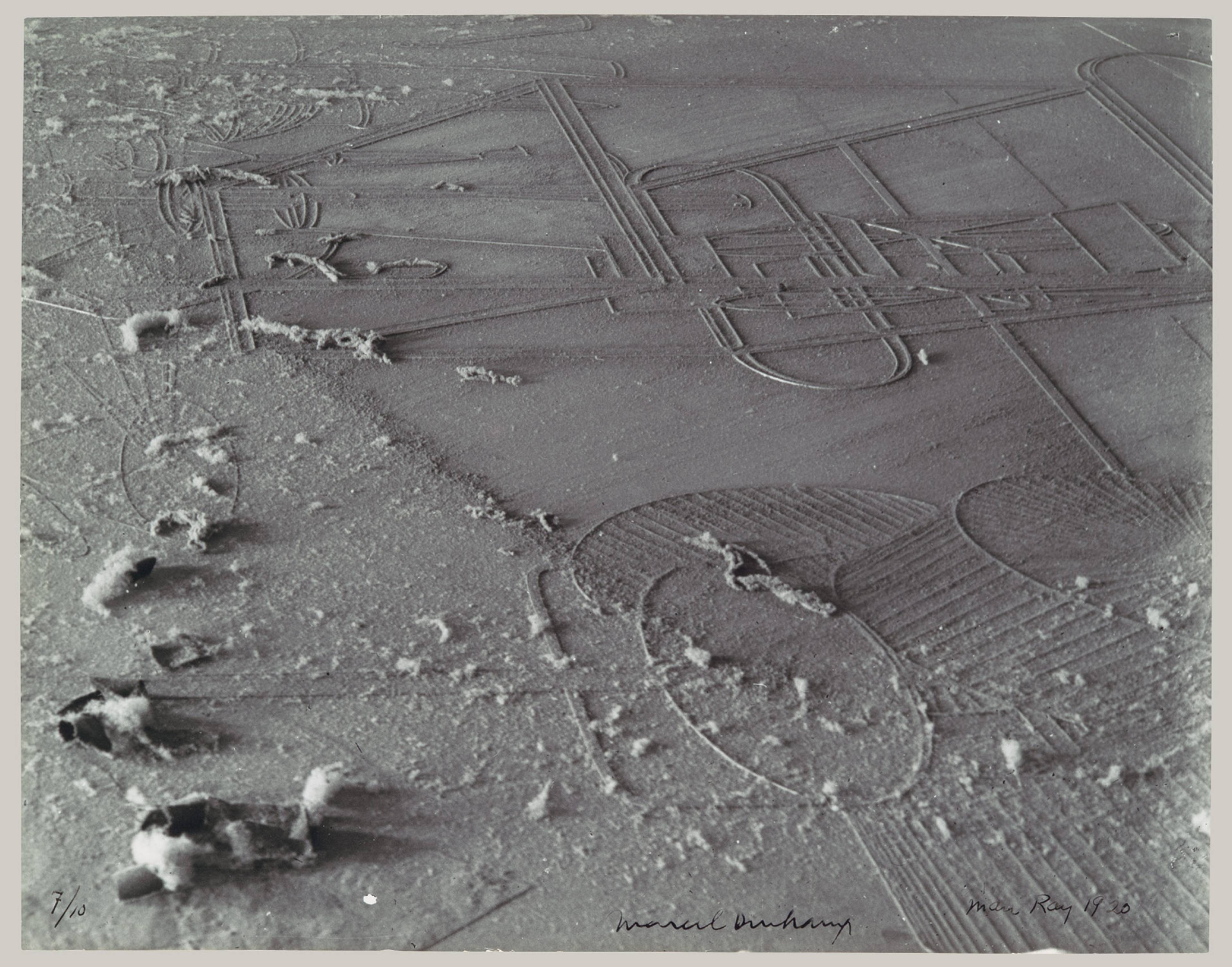

CS: I would have to correct myself: The use of dirt and dust is not underrated in contemporary art, but in conservation! Since Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray’s 1920 photograph Dust Breeding – an image of a sheet of glass that accumulated more than six months’ worth of dust in Duchamp’s studio before it becameThe Large Glass (1915–1923) – artists have been very interested in this ubiquitous matter that refuses to describe itself as any specific material. Both dust and dirt can be any material – diamond dust, pigment, gypsum, or ordinary dust bunnies under the bed. The fact that these two phenomena touch on taboos like hygiene and orderhas made them attractive for many artists in our time.

Whether dust and dirt are considered precious traces or unwanted impurities has been one of the central questions in conservation of cultural heritage since the 19th century. In these discussions, the question revolves around the significance of dirt as a “patina” with memory value, and around the critical discourse regarding the intervention of cleaning as an “interference of the human hand with the time-based evolution.” Since dirt and dust have, over the past decades, become some of the most fascinating occurrences in the iconological vocabulary of contemporary art, the challenge for conservators has become less about how to remove dirt, but rather how to preserve and maintain it.

Man Ray, Dust Breeding, 1920, gelatin silver print, 23.9 x 30.4 cm. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

EL: Can you share an example of when you had to preserve and maintain dirt and dust on an artwork?

CS: My first conscious encounter with dirt as a subtle artistic material was in the spring of 2002. I was in charge of conservation of the “Cremaster Cycle” show by Matthew Barney at Museum Ludwig, Cologne. In part two of the five-part narration, in which Barney draws analogies between the making of sculpture and genetic processes of reproduction in the human body, there is a structure in the shape of a partly open cabinet, The Cabinet of Harry Houdini (1999), made of nylon, salt, epoxy, and other materials.

Out of the cabinet’s opening, a multitude of dumbbells swells from a corset-shaped form onto the floor. During my last survey of the installation and condition-check on the works, I noticed a number of dark fingerprints and handling marks along the edges of the cabinet. In my tentative assumption to have gained a little more insight into Barney’s sense of perfection and cleanliness, after having worked with him for at least ten years, I asked the artist if he thought these stains should be removed before the opening. “No – not at all. These are the fingerprints of Harry Houdini – they show how he had struggled to escape the sealed cabinet.” Obviously, Barney himself had applied those prints to give the sculpture a narrative dimension. By removing this “accretion,” I would have destroyed the work.

One of the most striking differences between dust and dirt is that, while dust settles on things in the absence of people and activity, dirt stands for presence. Some artists are very attracted to the notion of dust as a metaphor for absence, negligence, or the passage of time. During a visit to Paul McCarthy’s studio, he took me up to an attic, where he had kept some of the bozzetti (clay models) for his large sculptures. A dense layer of dust had settled mainly on the surfaces of these beautiful, delicate, spontaneous clay sketches – he had not been up there in a while. Since we had just spoken about dust and absence, he decided to preserve the layer of dust by building a vitrine around the dusty sculptures, as a way to acknowledge the past and to put an end to this absence.

Preserving dust is technically the same as preserving any powdery substance, such as Yves Klein Blue pigment or pastel colors. As soon as you add medium to the pigment. it changes the tone and becomes more saturated. I have made tests to preserve desert dust on some more recent sculptures by Paul McCarthy (Coach Stage Stage Coach, 2019) by using a medicinal nebulizer. The advantage of this instrument is that the binding medium is atomized and settles evenly on and around each microscopic particle without touching it with any application tool. I think it went quite well.

A better term than “intention” might be the artist’s “sanction.” How do we find out? Study their work, compare similar works – or, ask the artists!

EL: I love the stories behind the shoes on Robert Gober’s series of leg sculptures cast from his own leg. For an artist who is known for his Americana-infused, remade ready-mades, he actually put real shoes on these leg sculptures. Can you tell the stories behind the shoes?

CS: From 1989 on, Gober made approximately twenty sculptures representing a single leg cast in wax from his own leg, coming out of – or disappearing into – the wall. During a short, intra-European flight frequented only by businessmen in gray suits, a small yet intimate detail about an attractive, cross-legged man across the aisle caught his attention: the reveal of flesh and privacy between the top of the sock and the trim of the trouser. Gober was intrigued: “I wanted to make a sculpture about that!”

Since I noticed that the shoes on all the sculptures – the brand is Alden – are slightly worn, I asked Gober if he himself had worn them. “No – there was this female cross-dresser in the East Village. I gave her some money and asked her to wear the shoes. ‘Come back in three months,’ I said. When she came back after three months, I looked at the shoes and said: ‘Come back in two weeks.’”

EL: Even though he used “readymade” shoes, he chose Alden – a patently high-quality, “handmade” American leather shoe.

CS: Gober never talked about why he used Alden shoes, but one can assume he did so because they represent a certain style and status. On the other hand, the cut-off chino trouser leg does not really represent business style, but a casual outfit. To properly display the body hair (Korean hair from a wig store that he inserted into the wax using tweezers) on the leg inside the trim of the trouser, a wire is inserted into the cuff to keep the rounded shape of the fabric.

EL: Engaging with artists’ intentions is an important part of your work. Is the artist always right?

CS: Well, yes and no. Or, to put it differently: The artist is always right, even if they are wrong! In my experience, especially at the beginning of their careers, artists do not worry too much about the longevity of their works. The impulse is often to try out something new, to make strange combinations of materials and see how it looks. Creativity and longevity do not always coincide – at least in the beginning.

To make art that is stable and lasting involves substantial skills, technological knowledge, and experience. Once an artist starts to show and begins to sell works, they may want to consider making their work a bit more durable and lasting. Collectors and museums mostly like to acquire work that is stable and ideally doesn’t change. Of course, there are artists who play with the notion of ephemerality. That’s also fine. It just has to be known to the collector that the nature of the work is to change and transform.

A particular challenge in the conservation of contemporary art is the use of non-traditional materials and combinations thereof, as well as unconventional techniques. Chewing gum is not a bad material per se (gum base, plasticizers, food-grade colors, sucrose) – but it is advisable to wash out the sugar before applying it onto canvas, as the sugar will start to drip onto the collector’s carpet when the climate fluctuates. Chocolate can be applied through a silkscreen onto photo-sensitive canvas, but it may need some stabilizing additives.

To respect the artist’s intention is the highest priority in conservation. What is the “intention?” We usually mean by intention the vision of how the artist has planned and conceived the work; it’s not always coming out the way it was planned. As the work develops, artists may change their minds, as creativity does not have a control function. The artist’s attitude in the making-of is important: the choice of material and working method, the overall appearance and visual stimulation, but also the context and artistic concept.

Therefore, a better term might be the artist’s “sanction.” How do we find out? Study their work, compare similar works – or, ask the artists!

Preserving contemporary art involves far more than just preserving the materials it is made of.

EL: In conserving a work by a living artist, how do you balance their intention and the expectations of collectors and gallerists?

CS: David Hammons made a series of beautiful “Rock Heads” (1998–2005). He glued short strands of Afro-textured curly hair onto the top of head-shaped granite rocks. Several of the works have a design similar to the shaved lines that barbers call slashes or part-ins. One of these sculptures was given to us for restoration. The owner had a particular design in mind, based on a photograph of a different Rock Head

I wrote to Hammons and asked if he remembered the design, or if he had any photographs of this work when it was first made, so I can see how the part-in would look. After a few days he responded: “Thinning hair is a natural part of aging. We should all look in the mirror and realize it.” The owner was also concerned with several particles of debris in the hair. When I asked Hammons, he said that’s part of the work. “It’s the hair as it was collected from the floor of the barbershop with a broom.”

David Hammons, Rock Head, 2005, rock and found hair mounted on pedestal, detailed. © Christian Scheidemann

EL: What about when it’s a collaborative work and the artists involved disagree on how the work should be conserved?

CS: A good example of artists disagreeing on the after-life of a collaborative work is Heidi, Midlife Crisis Trauma Center & Negative Media-Engram Abreaction Release Zone (1992) by Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley, which was inspired by the Swiss author Johanna Spyri’s novel Heidi (1880).The entire work consisted of a stage set, a group of rubber figures, two large backdrop paintings, and a videotape shot in the set. The set, a “schizophrenic collusion of Alpine decoration and reductive Modernism,” consisted of a chalet on one side and, on the other, the façade of the American Bar in Vienna, designed by the architect Adolf Loos.

Per McCarthy, it was executed by “a very bad carpenter”in Vienna according to the blueprints and a model provided by the artists. The construction itself consisted of more than 120 parts and pieces of cheap plywood. Since it was never intended to be disassembled and reinstalled, the joints were all nailed and glued, as they do in the Hollywood studios where McCarthy had worked as a student at USC. After the shooting in Vienna, the set was deinstalled, reassembled at Art Basel, and purchased by a Greek collector. In the following years, it was exhibited eight times in museums around the world, requiring four persons to install for four weeks, and at least one of the artists to position the props.

The plywood had suffered with each de-installation from pulling out the nails and shipment. The spackling paste had chipped in the joints, and the walls had to be repainted with each new installation. So, the collector asked one day if I could speak to both artists and find a way to stabilize the piece and consolidate the 120 elements into, say, twenty units. I talked to the artists and we all agreed on the task – as little as possible should be done to the walls. The structure and appearance should not change at all; only worn-out pieces should be replaced. With this concept, we would maintain the integrity of the work.

My role was to maintain the integrity of the sculpture as an artwork and an authentic document of its time, history, chance, and artistic intention, and not let it become a mere “technical problem.”

About thirty crates were shipped from Greece to Los Angeles, and we met in Mike Kelley’s studio, where the restoration would take place. After I had made clear that only invisible changes in the internal structure should be made, I flew back to New York. When I returned one week later, half of the house had been rebuilt. I got quite upset and told them to follow our initial concept of only minimal changes. Kelley argued: “Now is the chance to finally make the construction ‘right’ – it has never been done the right way.”

McCarthy was not happy with what was going on in Kelley’s studio. When the work was finished and a manual was made, he told me: “This is not my house anymore, my work is also about ‘covering up’ the imperfections – like in Hollywood.” Kelley, on the other hand, was not happy either, since he was not permitted to rebuild the set entirely. And I was unhappy since so much original material had been replaced. Both artists were unsatisfied, but for different reasons.

This example shows an almost hidden but important side of the artist’s attitude towards the afterlife of the artwork. McCarthy’s attitude is always to stay involved in the process and in the performance of the piece. He is aware of the disintegration and sees each re-installation as a ritual, a shamanistic way to reinvent the performance. Kelley, it seemed, was more interested in producing a solid work of art, an autonomous object in the spirit of Marcel Duchamp. While both artists agreed to create this sculpture/video set, they strongly disagreed on its afterlife. Preserving contemporary art involves far more than just preserving the materials it is made of.

Joseph Beuys, 7000 Eichen (7000 Oaks). Installation view, Dia Foundation in Chelsea, New York. Inaugurated in 1982 at Documenta, Kassel. © Christian Scheidemann

EL: You speak often of Joseph Beuys’s 7000 Oaks (1982) because of its dialogue between two materials – an oak tree and a basalt stele. Can you tell us about the project, and how its integrity has been compromised in its extension in New York?

CS: Under the motto Stadtverwaldung statt Stadtverwaltung (City Afforestation Instead of City Administration), 7000 Oaks was an encouragement from Beuys to the general public to plant trees in their neighborhoods. With the purchase of a certificate (500 Deutsche Mark) came a basalt stone from a quarry in Kassel and the instruction to plant an oak – or a similar, broad-leafed tree – next to the column, in the same bed of soil! Beuys’s intention was to show that, while the oak tree as an element of rejuvenation and social change would grow, the gap between the tree and the basalt column as a (pre-)historical marker would get narrower. However, in Dia’s Beuys installation on and around 22nd Street in Chelsea, this change is not going to happen: The trees are confined within metal grates, while the columns are firmly set in a bed of cement (apparently due to regulations set up by NYC Parks & Recreation).

With this installation, which Dia takes prides in having as one of eleven permanent site-specific art installations they maintain, things are getting more complicated. With a booming real-estate development in that area; thirty of the trees and twelve basalt stones have already mysteriously disappeared.

EL: It got even more problematic during Covid, when some restaurants unknowingly chopped down the trees to create outdoor dining tents. Until recently, you worked closely with living artists and advised them on materials and fabrication process.

CS: Naturally – with a background in art history, chemistry, and material science, conservators are particularly equipped to consult with artists in the use and application of certain unconventional materials and substances, i.e., a recipe for soap, an archival replacement for Pepto Bismol, or a banana that doesn’t rot. Or, we can help achieve a certain effect, like a recipe for an artificial silicone tongue dashing out of a hole in the wall as the visitor peeps inside, with the tip of the tongue still wiggling; protecting rose petals and kelp from fading and becoming brittle by osmotically exchanging the aqueous content with silicone oil; or developing non-yellow coatings to protect metal surfaces from oxidation, preserving potatoes through shock-freezing.

An image of 7000 Eichen (7000 Oaks) with the tree mistakenly removed to accommodate an outdoor dining tent during COVID in NYC. © Eugenia Lai

EL: Let’s talk about Wolf Vostell’s Concrete Traffic (1970)– an “action sculpture” commissioned by the MCA Chicago that is now “parked” in an indoor garage on campus at the University of Chicago where you are a visiting scholar this semester. It is a project that touches on the nature of conservation in all its complexities – I think it may even have been your most intense conservation project. A few weeks ago, you even dedicated a class to Concrete Traffic with a question “Can Fluxus be restored?”Can it?

CS: Concrete Traffic is an interesting case. Vostell was invited by the curator Jan van der Marck in the fall of 1969 to do something similar in Chicago to what he had just done in Cologne. Announced as an “Instant Happening,” he had poured several tons of concrete into a wooden mold that was built around his own family car (an Opel Kapitän) – with motor, lights, and radio on – before a roaring crowd of bystanders. As a preeminent figure in Fluxus, which emphasized the creative process over the finished product, Vostell combined two materials that represented the dystopia of his time: concrete, as in the shelters that still punctuated German cities and had recently been used to build the wall that divided Germany; and the car, as a vehicle of status and the cause of thousands of fatal accidents in post-war West Germany.

In 2012, Christine Mehring, a professor and German post-war art scholar at the University of Chicago, contacted me about conserving the Chicago iteration. Vostell had instructed the MCA by phone (the previous show at the MCA was Art by Telephone, 1969) to provide a sedan with fins and dagmars – unheard of in West Germany – and to have it cast in concrete in his presence. As things turned out, Vostell became sick shortly before the publicly announced pouring (Action Sculpture) and had to leave town; he never saw Concrete Traffic in person.

Since the sculpture, comprising thirteen tons of concrete and a defunct 1957 Cadillac, was parked on a university lawn and not “in traffic or parked in a desirable parking spot,” one goal was to get it back into its artist-intended context. Together with the University, we assembled a group of specialists: structural engineers, petrographs, chemists, a car conservator, and a concrete conservator. Christine activated the art history and philosophy departments – to think about the “true nature” of this “largest and most significant Fluxus object in America.” My role was to maintain the integrity of the sculpture as an artwork and an authentic document of its time, history, chance, and artistic intention, and not let it become a mere “technical problem.”

Wolf Vostell, Concrete Traffic, 1970, at its new permanent home in a parking garage at the University of Chicago. © Eugenia Lai

EL: When I look at your syllabus, I feel that it’s a statement of your conservation philosophy, as well as a distillation of your life’s work. Can you talk about how you devised it?

CS: I tried to address some of the complexities in negotiating between the physical nature (aging) and aesthetic sensation in an artwork, while maintaining the historical and conceptual integrity. Conservation today is not limited to the treatment of the physical artwork. It demands an open dialogue with varying stakeholders: the artist, collector, fabricator, curator, gallerist, dealer, shipper, and art handler, as well as with other specialized conservators and communities.

The title of my syllabus is borrowed from a show I visited in 2022 at the Bard Graduate Center in New York, “Conserving Active Matter.” What I found striking about its concept, which came out of a ten-year research project on the philosophy of and fashions in conservation, was the notion that “everything changes, anyways.” “Conserving Active Matter” addresses two aspects in conservation: one, that all physical matter is active, no matter how much you want to stabilize and stop it; and two, that people in all cultures are acting with different emphasis upon their cultural heritage.

___