The 21st century’s answer to Zola and Balzac, a punk-rock pulp-writer, iconoclast, and provocateur: Virginie Despentes has been hailed as all, all at once. A radical voice in French literature and cinema, she carved out a career writing about her years as a teenage sex worker in Baise-Moi (“Fuck Me”, 2003) and her 2006 manifesto, King Kong Theory, in which she told of being raped at seventeen while hitchhiking with a friend. Long notorious, she finally received international critical recognition with the nomination of the first novel of her Vernon Subutex trilogy (2015–17) for the International Booker Prize.

In 2022, as France grappled with its riposte to the #MeToo movement – #Balancetonporc, or #Squealonyourpig – Despentes published Cher connard [Dear Dickhead], an epistolary novel that follows Rebecca, an aging movie star, and Oscar, a Houellebecqian, forty-ish writer who attacks her online. A heated exchange ensues, only for things to turn even messier when Zoé, Oscar’s former assistant, accuses him of sexual harassment online. With characteristic wit and raw honesty, its a meditation on fame, getting older, addiction, and patriarchy. But more than that: Written by an author who calls anger her “foundation stone,” it asks us if we might find the power to forgive.

Katie Tobin: Dear Dickhead is structured around an email correspondence between Oscar and Rebecca. What drew you to this format? And how did it allow you to develop their dynamic in ways that a traditional narrative might not have?

Virginie Despentes: First, I’m very attracted to the form as a reader. It’s a very particular way to talk: It’s not a dialogue or a monologue, and you don’t talk about yourself the same way when writing a letter. I was really interested in what occurs when you write to someone and that someone answers. I’d just published three books, the Vernon Subutex trilogy, and not wanting to repeat the style I’d worked in for five years, this was a way to technically break free from that. I’m very interested in the conscious dreaming of people, and I knew that, if I was going through letters, I would find another sound, another rhythm, another way of expressing the self and talking to someone else. That’s the architecture, the shape and the form that the book took. As for the subject, I really wanted to talk about addiction and drugs, as I’d just read some really good books and essays about those topics.

KT: Did you feel restricted by the form in any way?

VD: No. Because I used to write a lot of letters, I know that it’s a very intimate form of address. You can sense that when you read letters like [the late novelist] George Sand’s. You really know everything about her daily life, about her work, about her political views. I was interested in the fact that you can put anything in a letter.

In France, we had some men saying that they wanted to deconstruct masculinity. And the first thing they said was: “We have to really understand when a woman says yes or no.” But I would say the first thing they should think about is: What’s going on with their fucking libido?

KT: Both Oscar and Rebecca come from working-class backgrounds. How does class mobility shape the way that they see themselves? Do you think it makes them more defensive?

VD: Yes, they’re cleverer and wittier, also more aware. I think there is a certain stupidity in high society, whereas if you come from a working-class background, you’ve had to adapt a lot, to be quick, to survive, to find solutions. They know there is danger, that they can be threatened, and they are sensitive to how precarious it all is. They don’t feel the security that they would have felt if they were born wealthy.

KT: There’s been lots of praise for Frank Wynne’s translation of your book. How involved were you with that? Are there any aspects of your style that are especially hard to translate to other languages? I read somewhere that the title was also known as “Dear Asshole” in English.

VD: Yeah, it’s difficult. I have a very precise style in French. I work with slang and with incorrections and with errors. I don’t read aloud what I write – you can’t, really. But Frank is doing an amazing job because he’s a writer himself. It can’t be exactly the same. It has to be transposed, like a remix. Finding a translator I trust is very important for me – it’s really a relief to know I can rely on them. And the translation has to be their own sound; I would say, more New Wave and less punk rock. Frank is more sophisticated than me. You can tell in the results, and I love that.

Women want a little bit of sunlight and sweetness and care and tenderness, things that other women might love to do with them. At the moment, I feel so grateful I’m a lesbian.

KT: The book was published originally in 2022. Has the culture around survivors of sexual abuse in France changed much since then?

VD: This year in France, we are facing a big backlash from some women – white women – coming together as a group to say: “That’s enough, ladies.” They are deciding who is a “good” victim and who is a “good” aggressor. At the same time, we have the case of Gisèle Pelicot [EDITOR’S NOTE: who was found to have been serially drugged by her husband and raped by strangers he recruited on the internet, all fifty-one of whom have been convicted], which has had huge repercussions on social media. You can see things are happening with the #MeToo movement. It’s a work in process, it’s a revolution in process.

The subject of male heterosexuality is something we need to think about. In France, we had some men saying that they wanted to deconstruct masculinity. And the first thing they said was: “We have to really understand when a woman says yes or no.” But I would say the first thing they should think about is: What’s going on with their fucking libido? What’s wrong? Can they take care of their own libido, so maybe saying yes or no wouldn’t be such a problem? Because who would say yes to such a sick desire? What’s going on with them is really sinister.

Women want a little bit of sunlight and sweetness and care and tenderness, things that other women might love to do with them. At the moment, I feel so grateful I’m a lesbian.

KT: How useful do you think social media is for facilitating these conversations around justice and gender?

VD: Social media is what made it possible. Before, it was impossible to talk about these subjects. Say I was a journalist who wanted to write an article about being sexually harassed in the street. My supervisor would be a man, and he would have told me there’s no touching that kind of subject. What has made it possible is the fact that someone – a woman or young woman – can now say this is happening, and thousands of women will answer: “I know what you’re talking about and I believe you, because it’s happened to me.” You have to have social media for that.

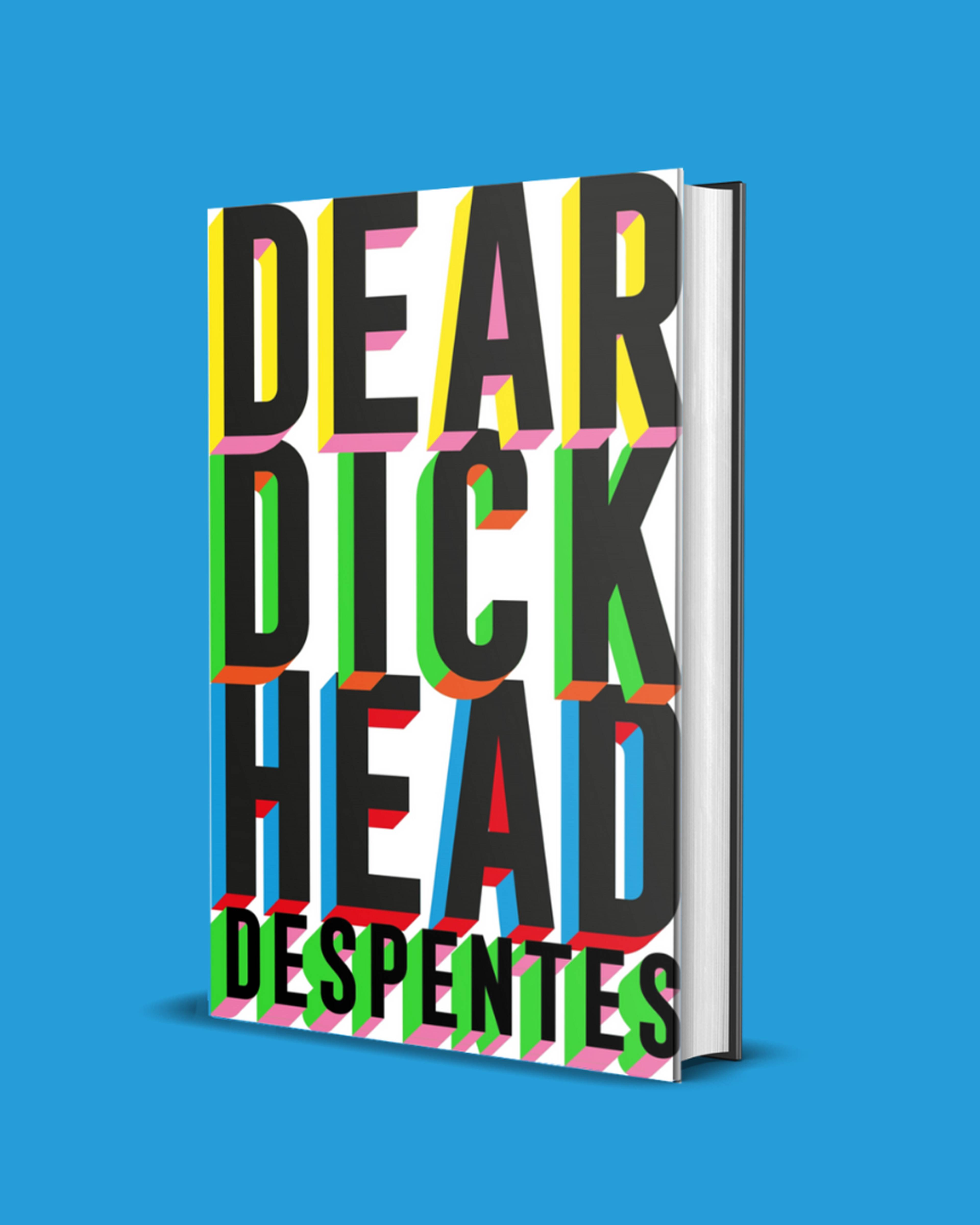

Virginie Despentes, Dear Dickhead, 2024

KT: There’s a departure in Dear Dickhead from the mood of Vernon Subutex or Baise-Moi. How did you approach writing about similar subjects through a slightly more optimistic and redemptive perspective?

VD: I wrote Baise-Moi more than thirty years ago. I can see similarities between the subjects, but I also see big differences. The characters there were outcasts and misfits. In Dear Dickhead, they don’t fit in exactly where they are. They weren’t born into a world where they are supposed to become actresses or writers, to express themselves as artistic. Baise-Moi was also centered on a very violent rape. Here, you have a guy who is trying to have an affair with a girl who doesn’t want to, which is not the same level of aggressive hostility, nor is it the same kind of victim. Zoé Katana [in Dear Dickhead] is also very diffident from the Baise-Moi girls.

And obviously, in thirty years, my writing process has changed drastically. I’ve published nine or ten books, so I can now say my entire life has been playing with what I write and who I write for. What do I have to say? I wrote Dear Dickhead after the first year of the pandemic and the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine. I was witnessing so much distress, and for the first time in my life, I wrote thinking that I wanted to bring something a little positive with this book – something that makes you feel a little bit better.

Ursula Le Guin always talks about bringing utopia, and I see Dear Dickhead as a new kind of utopian book. Oscar’s redemption is possible. He first defends himself and sees himself as a victim –“I’ve done nothing, they’re attacking me, I’m alone” – but slowly, through the friendship with Rebecca and through his own process, he begins to think: “I need to understand what I’ve done wrong.” This, for me, is a utopia: I don’t see a lot of men going through the process of understanding, and I think the world will be a different place if people do find the space to understand what we’re talking about when we say something is wrong. Here, it’s a male character in a #MeToo situation, but I would also say it’s very important for people with power to understand why people are complaining so much. That would begin a dialogue, I hope. Then, maybe, we can change the situation together.

The question of redemption is always a difficult one. What do we do with people? What do we do with justice in general? Obviously, sending some of them to jail isn’t really a solution, in the same way that cancel culture only helps up to a certain point.

KT: One of my favorite moments is when Rebecca comforts Oscar when he’s tempted to start using drugs again. She says, “All we can do is think ‘I hope it will pass’ and be there afterwards, praying that there will be something left of the friend that you had, and then let it go.” You’ve touched on this a bit already, but how do you see the book fitting into a broader conversation about redemption and cancel culture today?

VD: The question of redemption is always a difficult one. What do we do with people? What do we do with justice in general? Obviously, sending some of them to jail isn’t really a solution, in the same way that cancel culture only helps up to a certain point. Either you try to change things and make some room for redemption, or you look for a process to make them change, while making room for the victim to talk about what happened to her and how she can be restored. Beyond what we do to aggressor, we have to have concern for the survivor. What can we do to help them heal?

If someone can have a look at you and your vulnerabilities and your wrongs, I think it can help you to change. The whole idea of the book is that friendship is an opportunity to open yourself to more sincerity because you trust the other. It’s this little utopia again. I’m not sure it’s true, but I was sure I wanted to write a story about it.

Rebecca also changes through this friendship. It’s not only her helping Oscar; he is also helping her to go through a process that’s very particular for women: aging, especially past your fifties. She used to be a beautiful actress, and I would say that her friendship with Oscar helps her to connect better with herself, with the world, with Zoé’s generation, and with what Zoé has to say.

KT: We’re nearing the 25th anniversary of the film adaptation of Baise-Moi. In the UK, it remains something of a set text when focusing on censorship in cinema. In our current cinematic climate, is there still a need to confront audiences in this way?

VD: I would say it’s worse than ever. I think removing sex from mainstream cinema created a significant problem, as it pushed the depiction of sex into the more clandestine spaces of the internet. This shift resulted in a very different kind of pornography from what we had in the 90s. If we had some money, more exposure, and the possibility to talk about what we are showing, pornography might be very different. I think the normalization of this type of pornography has led to a worse culture for actresses, but it also made things worse for us viewers. If there is a place where we can talk about our sexuality, our desire, the complexity – or not – of it, then maybe something can change. But taking sex out of the movie industry has also meant taking it out of social media – you can’t even show a tit. It’s a taboo – an absolute taboo – in both representation and discussion, yet everybody still sees it, children included.

Again, it leads me to wonder when men are going to openly talk about their sexuality. I believe something is really going wrong here, and I think we need to open cinema to these themes – censorship was never the right decision. Saying that sexuality doesn’t belong to public conversation was a really religious choice, and was part of the rise of the extreme right.

So, yeah, there’s something very wrong with the movie industry today, as is the fact that we accepted it as filmmakers or as artists. It was a submission to the power of people with a particular agenda, who are directly telling us: “Shut the fuck up.” It’s the same “shut the fuck up” as in the #MeToo movement. They think that those aggressions – rape, incest, pedophilia, our sexuality in general – should belong to silence and darkness, that we shouldn’t talk or write about them. But I am trying to think about a better way to live and to write about it, too.

___

Virginie Despentes’s Dear Dickhead (2024) is published by Quercus / Hatchette UK, translated into English Frank Wynne.