Sitting in bed, I put my hand down to adjust my position. As I pushed myself forward, I heard a long rip across the back of the tail of my pajama shirt. I hadn’t even known it was under my hand. How did I do this: the unbelievable, the irreversible. How did what I thought was a robust garment tear so easily? How didn’t I pick my hand up quicker? What is left of the shirt? Can I call it a garment in the same way at all?

At what point does a piece of clothing become unwearable? I will mend it, of course, but what will become of it? It functions just as it did before but the joy it provided in wearing, which was one of its principal functions – after all I could go to bed naked – is severely diminished. The rip is not even in a very visible place, and this is not a shirt many people see, but its thick white poplin has given me a lot of pleasure, and part of this pleasure was its creamy, united perfection.

You never know how a garment will leave you, whether it will wear into holes, or snag its pocket on a doorknob (this has happened) or whether you, the wearer, will wear out first, and your inheritors will wonder what to do with a “perfectly good” yellow cardigan or tomato girl synthetic slacks. Polyester has a half-life of anything from twenty to two hundred years, the radioactive particle of fabric. Now that so few clothes leave us from pure wear and tear, when they do, it’s hard to know when to let them go.

Celia Pym, Norwegian Sweater, 2010

Some garments go on without us. Fashion museums are records of anti-taste, showing what wasn’t worn – because the clothes were “too good” to wear every day, or because their owners were rich and those particular garments were occasion wear or neglected mistake purchases. I have my own fashion mausoleum: a silk shirt I refuse to dry-clean, am too lazy to hand-wash, a double-breasted jacket that looks formal even twinned with track pants – clothes that will never “be me.”

Clothes used to “be you” because you didn’t have that many. Before the internet resale market, whatever you bought, you wore, for what seemed more or less forever. There could be no mistakes. But, with resale, looks are no longer immutable. Now I can ask – and often – is it me? Is it still me? Am I still “it”? Online, I sell almost as often as I buy: one in, one out. I have a small wardrobe, not metaphorically but literally, and I hate to see garments hang around unworn. Or maybe I want to discard past selves. This is increasingly low-risk as almost everything I’ve ever desired is available now and I have sometimes bought a discarded version of myself back. Almost always, someone, somewhere – on Vinted, or Depop, or Ebay – has all those pieces I couldn’t afford new, that I missed out on in the sales; the ideal versions of all the garments I’ve bought dupes of, or bought in the wrong size or the wrong color because I wanted the original so much they seemed adjacent enough. Plus those garments I’ve worn out. I could replay my sartorial history all over again. But do I want it?

There’s nothing more boho than pre-ripped jeans. As the symbolist poet Jean-Marie-Mathias-Philippe-Auguste, comte de Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, wrote, “living? our servants will do that for us.”

I buy most of my clothes second-hand, and I’m here for the marks of other people’s wear. Damage is what makes an item personal and some clothes look better worn: an army jacket I picked up second-hand in France, my friend Zan’s unironed vintage men’s shirts, each curling collar worn into delicately toothed holes as though they’d chewed on them; each speaking not only of that particular shirt in its individual state of decay, but a whole way of life in the Irish countryside that is perhaps decaying, or maybe thriving for the very reason that it welcomes disintegration.

Clothes are never not also bodies, and sometimes people tear before their clothes do. The poet Anne Boyer, in her memoir The Undying (2019), describes how she toured thrift stores to find clothes soft enough to hold her body through chemotherapy. Thrift stores mean thrift for the buyer and thrift for the doner – because nothing goes to waste, they promote the relic of a particularly American idea of puritan virtue (“thrifting” is a US verb). But, like those values, second-hand is, ironically, related to consumption. At Vinted prices, as soon as you see a look, you can make it happen.

Jane Birkin holding one of her "Birkin-ified" Hermès bags

Online I see resale garments I know are priced too high. They are the remnants of their owners’ desire, unable to let go of the dreams they cherished, the emotional or financial investment involved, to actually make a sale. Is this entropy? A garment’s emotional price can be zero to infinite.

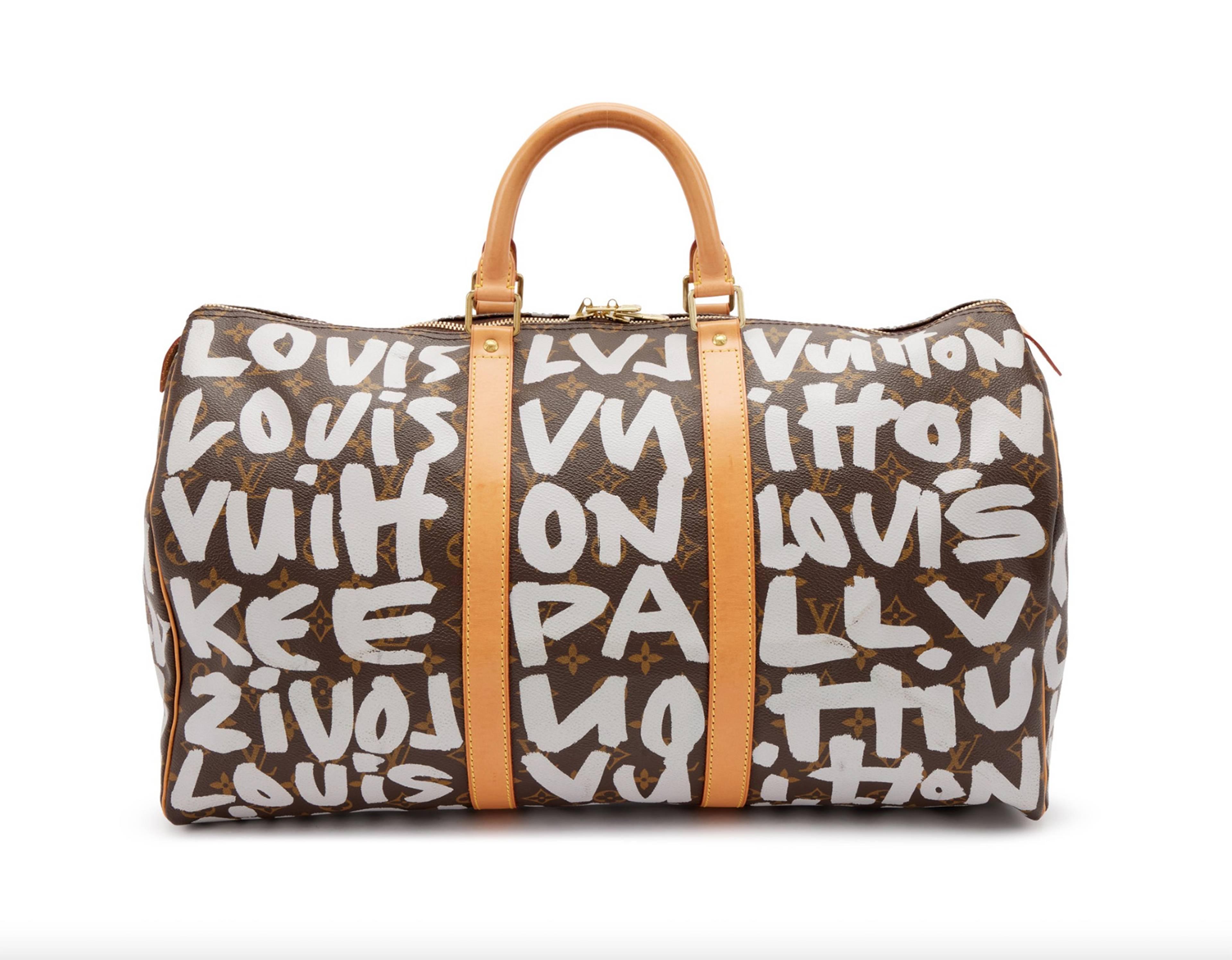

In 2021, four years before her death, Jane Birkin’s Hermes Birkin bag sold for £119,000, five times its pre-sale estimate because, not despite the stickers she’d plastered it with. “This bag shows wonderful signs of use by Birkin,” said Meg Randell, head of the Designer Handbags & Fashion at Bonhams Auction House. As well as Birkin’s signature, the auctioned bag had a “red cord tied around one of the handles, and bite marks from Birkin’s cat on the handle.”A certain laissez-faire, or – no, deliberate destruction, tipp-ex’d leather jackets and laddered fishnets – can look like a strike against capitalism. But any sartorial gesture can be recuperated. In 2001, Louis Vuitton collaborated with the artist and designer Stephen Sprouse to graffiti its own bags, and I can’t even find a date for the first Balenciaga graffiti denim jackets, which is possibly complicated by the suspicious number of cheap versions available on resale sites.

Louis Vuitton x Stephen Sprouse graffiti bag, SS 2001

Balenciaga Graffiti Denim Jacket SS 2019

There’s nothing more boho than pre-ripped jeans. As the symbolist poet Jean-Marie-Mathias-Philippe-Auguste, comte de Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, wrote, “living? our servants will do that for us.” Distressing, like that saying about cheap shoes, has become something for the rich, while the late great Vivienne Westwood, a designer from the kind of background that’s sometimes called “humble,” (though there was nothing humble about her), switched from the ripped-up punk of her early “Destroy” collection to the kind of crinolines once seen on little girls’ birthday cakes, a waist-severed Barbie (still smiling) emerging from icing frills. Let them eat cake? Appropriating Marie Antoinette’s catchphrase, Westwood’s most radical sartorial gesture was one the French queen would have eaten her heart out for.

Malcolm McLaren & Vivienne Westwood, “Destroy” muslin shirt, 1977