Caenorhabditis elegans, the miniscule worm called the nematode, has exactly 302 brain cells. That’s big enough to be interesting, but small enough to chart its every interconnection. In fact, with modest computing power, one can emulate the creature’s brain – a godly experiment performed in 2025 by artist Harris Rosenblum. His work, programmed by Karyn Nakamura and titled Infinite Pain, simulates a nematode brain on a gaming PC. Every few minutes, supposedly, the nematode receives the signal for pain.

The piece presents as a moral quandary. It’s a virtual brain, so – is it virtual pain? And if so, does that count as actual cruelty? Never mind that some people doubt that “lower animals,” virtual or otherwise, can feel pain at all. The piece conveys a negative aura simply in that the artists decided to build a torture chamber. Why not a nematode orgasmatron?

Because the question of morality vis-à-vis a digital worm is less interesting than the flagrant gesture of cruelty (or its appearance) when the prevailing winds say art should be a force for good. “Against Morality,” a book-length essay by critic Rosanna McLaughlin published earlier this year, is part of a backlash. How ridiculous, she writes, that a curatorial statement would squeeze the nuance out of a morally complex artwork, and instead frame the experience of art as simply uplifting or edifying. Case in point: the group effort, circa 2022, to position Philip Guston’s deliriously ambivalent Ku Klux Klan pictures as anti-racist.

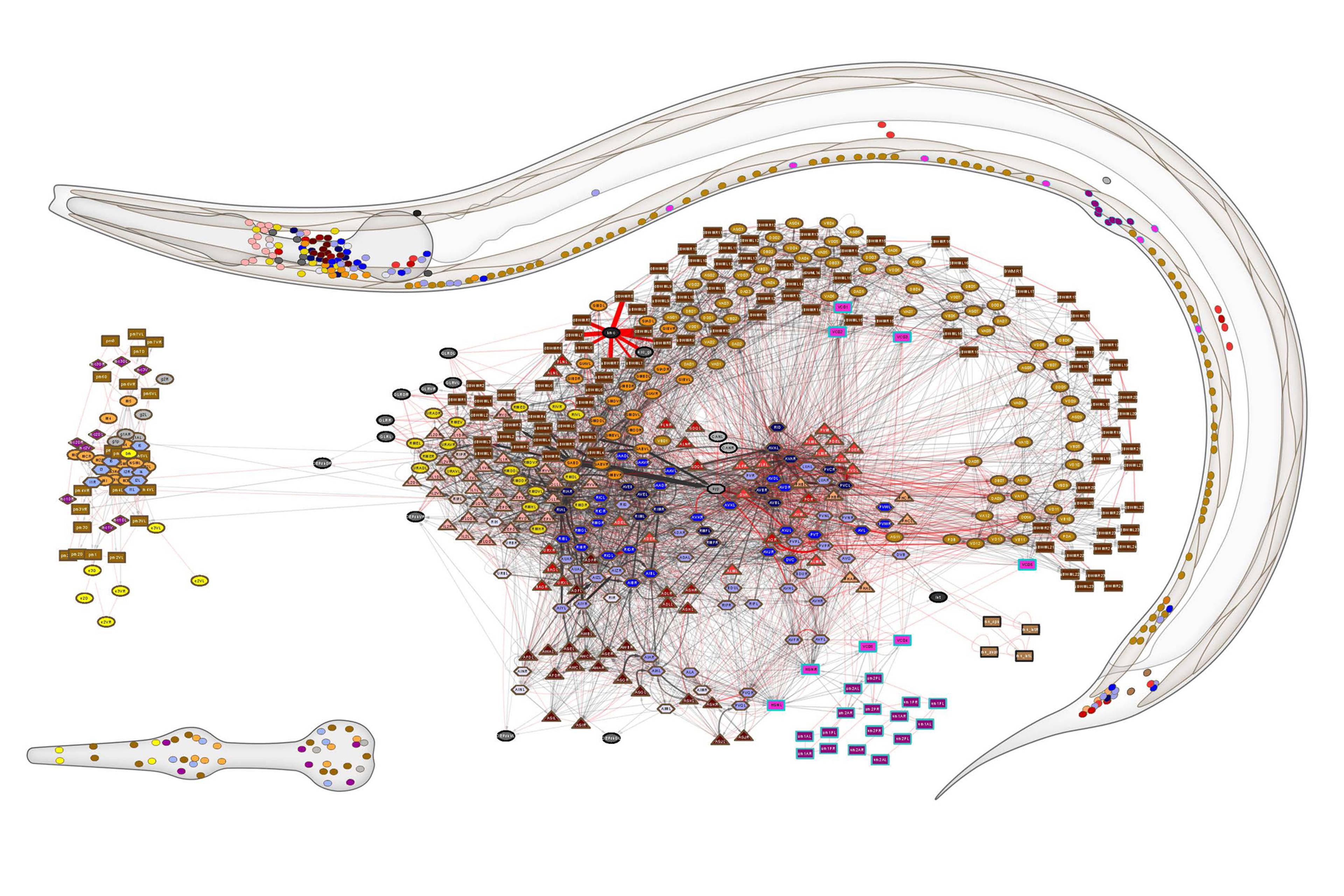

Major nerve tracts and ganglia of a hermaphrodite nematode. Published in Cook, S.J., Jarrell, T.A., Brittin, C.A. et al. Whole-animal connectomes of both Caenorhabditis elegans sexes. Nature 571, 63–71, 2019

Harris Rosenblum, Infinite Pain, 2025, various media, dimensions variable. Courtesy: the artist; SARA’S; and Foreign & Domestic, New York. Photo: Stephen Faught

McLaughlin adds amoral invective to the broad annoyance leveled at institutions eager to be “on the right side of history” (or at least not on the wrong one) at the expense of the art – variously phrased by writers as diverse as Brad Troemel, Rahel Aima, and Dean Kissick (who spoke with McLaughlin at her book launch at the ICA, London). I’m not as convinced that morality is ruining art. The tendency to wrap artworks in a protective fluff of progressive politics is real, and often absurd – but it’s just one way people in this industry feel compelled to boil down complex themes into absolutes, in hopes of an attention payout in the casino of online life.

Interesting that McLaughlin begins her book with a personal anecdote. One day, while scrolling through bruisy, handsy paintings of bellhops by Chaïm Soutine, circa 1925, she came across a review praising the painter as someone who “sympathetically drifted to the underclass.” Furious at this flattening, she drew a hot bath to flush her body of cortisol. The first-person framing is telling, and familiar: An assessment of an artwork is directed into the void, at an imagined audience, more or less stereotyped. But the recipient of this meme takes individual offense. The wall label or art review talks down to you – you! – and insults your special intelligence. The insult cannot stand without retort.

Chaïm Soutine, Le Groom, 1925, oil on canvas, 98 × 80.5 cm. © Centre Pompidou, Paris

Developing an observation into a theory is a time-honored intellectual method. But taking general statements personally speaks to our parasocial environment, characterized by one-way relationships with people we will never meet. The feeling of being wronged by a broadcast, like a tweet or an art show – and its corollary, the fear of being targeted by a stan army for broadcasting what you really think – fuels the politics of grievance.

It’s been observed that the pain of others is hard to comprehend, and that living through similar pain isn’t always enough. Online, cruelty comes more naturally. This is part of why farmed outrage achieves viral momentum – and easily cues public displays of moral indignation. Stark certainty, however performative, makes a good meme. But ambivalence is antimemetic. Is it brave, then, to broadcast ambivalence? To state a complex thought, even when it’s guaranteed to be misunderstood? Guaranteed, even, not to go viral?

Framing Guston’s KKK paintings as anti-racist might seem like a bulwark against the cruelty technology makes so easy. It’s a moral reaction. But you don’t need an artwork to tell you what you already know.

Meme virality, the transmissibility and severity of ideas, is the subject of another recent book, Antimemetics (2025), by tech critic Nadia Asparouhova. Sometimes, an idea burns through a population quickly and is quickly forgotten (like norovirus, she says); sometimes, it lingers, chronic or dormant (like a parasite). A shitcoin is a meme – superficial and swift. The culture wars are a supermeme, both consequential and highly contagious. Taboos, secrets, subcultures – consequential but slow – are antimemes.

There’s a moral tug to memetics, too. Strained by demands on our attention, Asparouhova admits it would be nice to have some standard of judgment: “Is it equally ‘good’ to focus on human rights activism, versus spending time with my family, versus scrolling on Twitter all day?” But the reality is that each person must make these choices for themselves. “Refusing to engage with difficult ideas – even those that point towards the deep suffering of our fellow humans – does not necessarily make us cruel and callous,” she writes, “or even selfish.”

Philip Guston, The Studio, 1969, oil on canvas, 121.9 x 106.7 cm. © The Estate of Philip Guston

The time period both McLaughlin and Asparouhova cover – the last ten years or so – coincides with the well-chronicled memetic evils of the internet – an amoral-cum-immoral realpolitik, where cruelty (toward immigrants, say) is portrayed as merely expedient, and empathy is mocked. Framing Guston’s KKK paintings as anti-racist might seem like a bulwark against the cruelty technology makes so easy. It’s a moral reaction. But you don’t need an artwork to tell you what you already know.

That people are assholes online, and that a kind of nuance is only possible in personal exchange, is essentially the question raised by Rosenblum’s virtual nematode, and the reason its amoral energy moves less through the digital worm than through the audience. McLaughlin advocates for art that “gives form to the complex experience of being human, of walking the earth in a decaying suit of flesh.” For Asparouhova, the interstitial universe of antimemes is what lets us escape from the paralyzing extremes of memetics. Antimemes circulate in secret, or slowly, until they’re pushed into the light by truth-tellers and tricksters, like artists. “A trickster is not immoral, but amoral,” she writes. “His purpose is to remind us of the complexities and ambiguities of life.” Dealing in taboos, in sub-rosa and subcultural fashion, in visions of social progress, has been one of art’s powers since at least Dada. But whatever good comes from art takes a circuitous, even painful path.