Wildness is not a deficit of painting, it turns out, nor of behaviour in general. Decorum is old hat, and today’s sensibilities have moved so far away from the modernist experiments that the seem to be coming around again, catching a few penises along the way. Why? What is it about this moment that make it rife for such retakes?

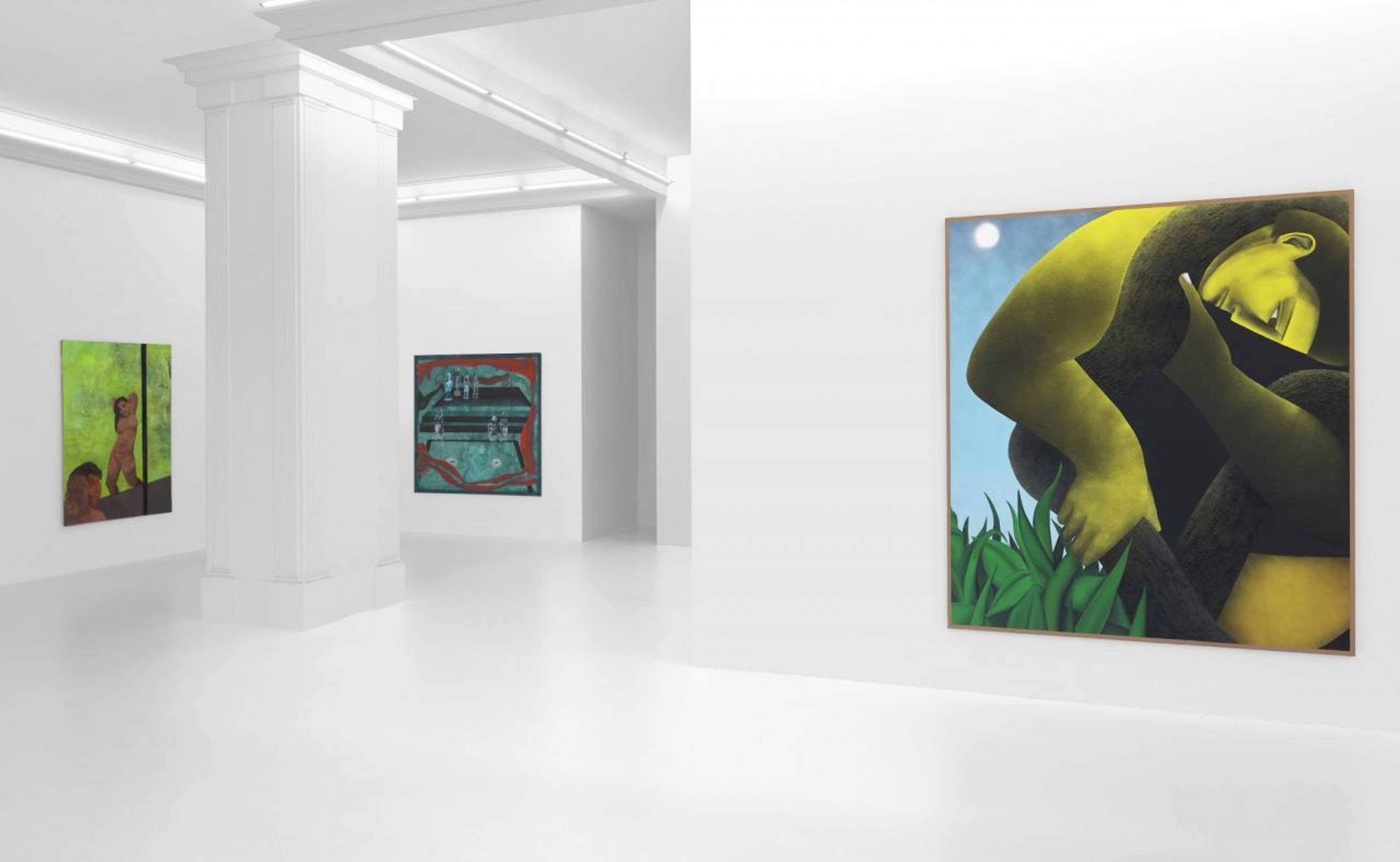

Such is the context for the vibrant and at times psychedelic group show at Peres Projects in Berlin, “what fruit it bears”, which features works from thirteen different artists, almost all of which were made in the last year. The palette is not just loud, it’s often blinding, neon greens and yellows, enough to make your eyes see funny things when you look away and catch the pristine white walls of the gallery’s two spaces. This was a trick of the trade for the original Fauves, who were not shy about using the effects of complementary colours (lots of greens with red, blues with orange, and so on).

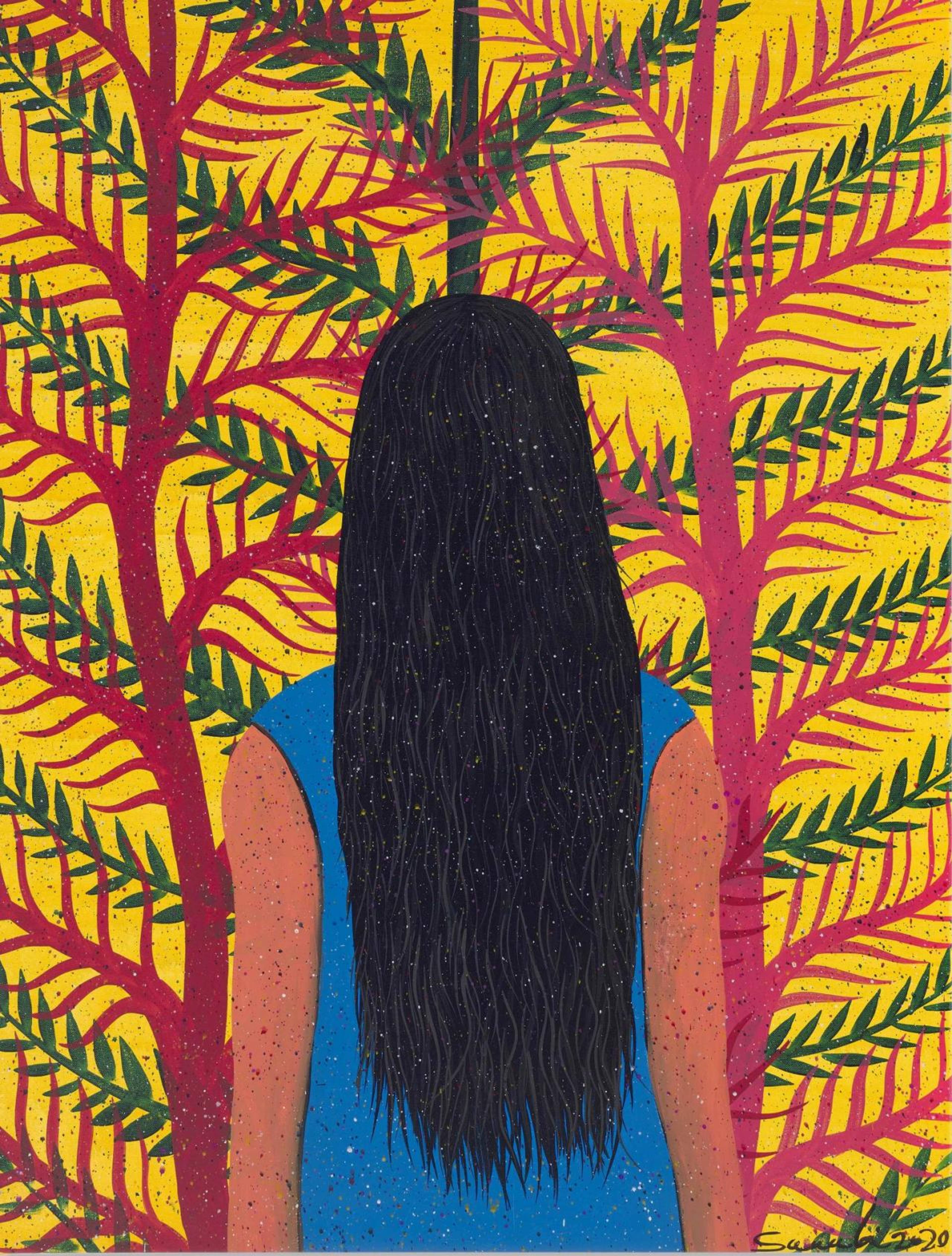

In Berlin-based Shota Nakamura’s (*1987) two works on paper (both 2020), Untitled (ribbon-strings-prisms) and Untitled (day-night) the delicate contours of leaves and drips move listlessly across a beachball (or umbrella), a pink butterfly that looks like bowtie, and a tree that divides the space of the paper into two vertical sections, one blue, the other an orangey-yellow. The tree and its vertical division return in Mostafa Sarabi’s (*1983) painting Untitled (2020), where a central figure with long black hair has turned her back us, her rounded silhouette a stark contrast to the pointer ornamental motifs that surround her.

Mostafa Sarabi, Untitled, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 130 x 95 cm

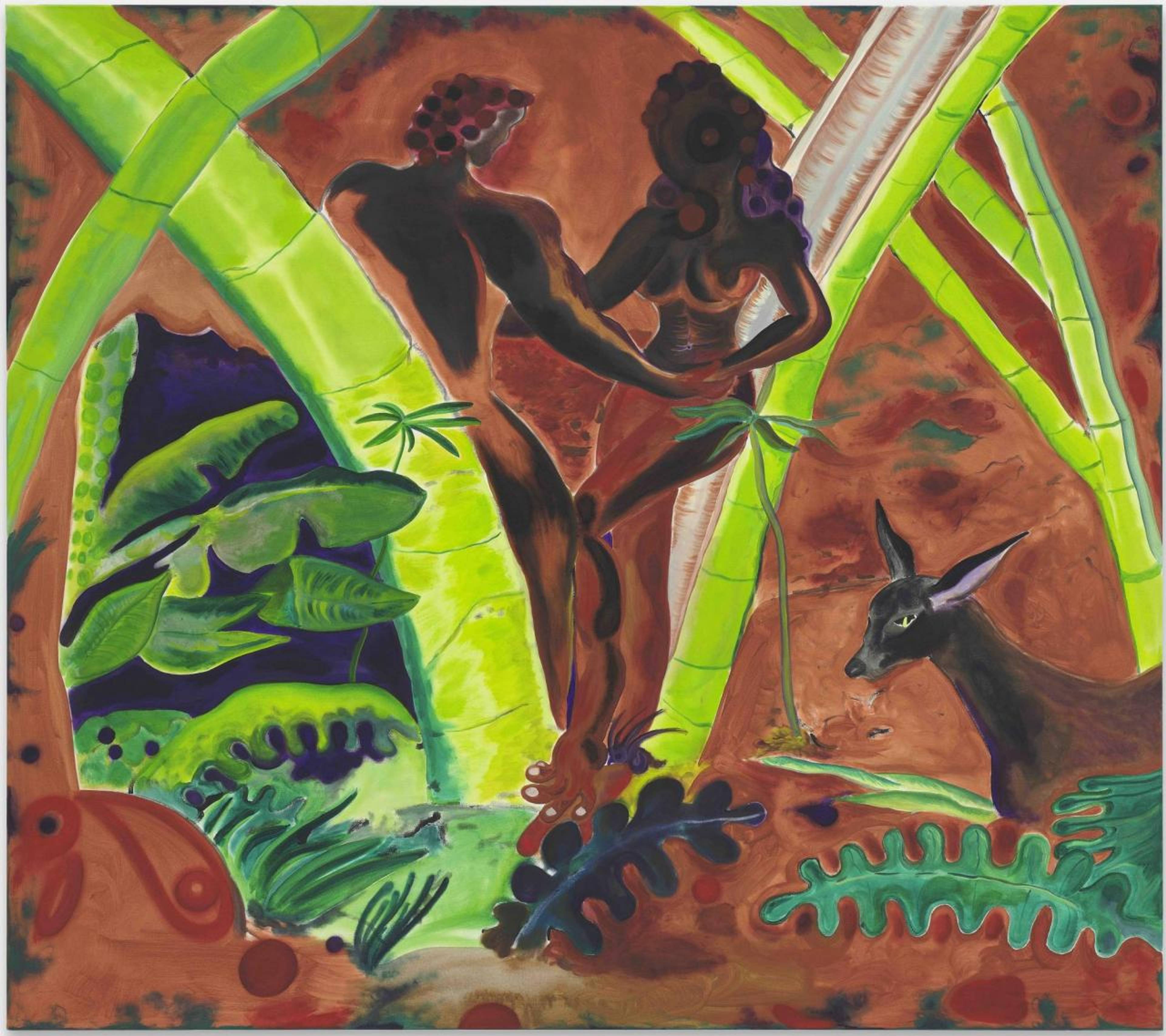

The lightness and wind-swept dreamy character of these works certainly smacks of earlier precedents, but not overtly, unlike a few paintings that appear to cite the Western modernist canon quite specifically. Vojtěch Kovařík’s (*1993) Laocoon (2020) looks like a cross between a Henri Rousseau landscape and a Picasso portrait, with a large, crouching central figure shaded heavily in contrasts between a mustardy yellow and deep browns and blacks. Stanislava Kovalcikova’s (*1988) Weight of Light (2020) is a playful update to Paul Gauguin’s colonialist gaze on the Tahitian female figure. In this painting, however, we have full frontal and what looks to be a stripper pole, the background a wall of green somewhere between mushy peas and puke. The landscape is not a calm surface, nor a site of projection, but a field contaminated by the presence of giants and their tainted histories. Take Nicholas Grafia’s (*1990) portrait of two figures framed by neon yellow palms and cute little greenery (again, both facing away). Unlike Sarabi’s portrait, though, there is something that returns our eye: a donkey who enters stage right and peers at us in profile. The feeling is not disconcerting or even uncomfortable. The donkey might be sharing our suspicion about the ludicrous fantasies of nature happening around, “do you buy this shit?”, the donkey might be uttering to us, “Am I right?” I don’t even know if it’s a donkey, it could be a goat. Who knows? Who cares? The effect is the same either way. Like Grafia’s, much of the work on display treats pictorial space as a cramped and crowded affair, invaded, by the whims of imagination or the fear of uncertainty.

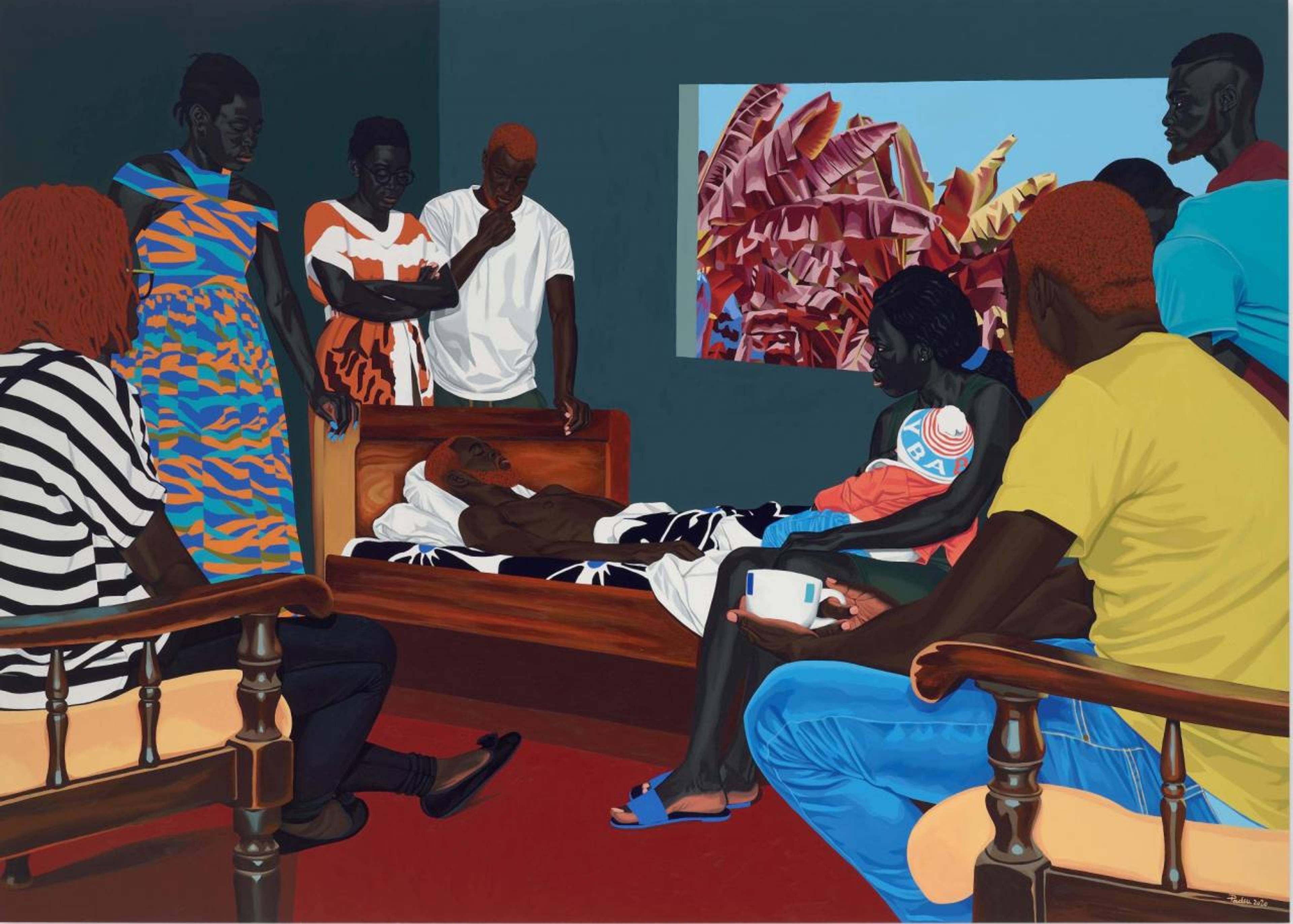

Marc Padeu, Les derniers jours de Damien, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 200 x 280 cm.

There are more sombre moments, too, like Marc Padeu’s (*1990) Les derniers jours de Damien (the last days of Damien), a group portrait of figures surrounding the bed of a dying figure, which we can barely make out. Some of the characters depicted sport incredible garments, whose edgy abstraction complicates the colloquial lamentation scene. Each body, it seems, can be decorated, adorned, or even turned into the ornament of another’s fantasy, all of which meld with the restrictions provided by the two-dimensional medium. What animates these and other pieces at Peres Projects is the a softness, the absence of any kind of frustrated, gestural emission. The easiness of looking is compounded by the difficulty of the subjects treated, baptised as they are in the fires of that project called modernity. There’s a metaphor somewhere, but the references are mine, not necessarily those of the artists. But on the former Stalin Allee in the Soviet architecture of Friedrichshain in Berlin, the colour is a sight for sore eyes, whomever is meant to be addressed and take all of this in.

Shota Nakamura, Untitled (ribbon-strings-prisms), 2020, colored pencil on paper, 167 x 98 cm

Dalton Gata, Esculturas I, 2020, ink and graphite on paper, 76 x 112 cm

Nicholas Grafia, Malakas & Maganda, 2020, acrylics and tinting paint on canvas, 160 x 180 cm

Stanislava Kovalcikova, Weight of Light, 2020, oil and ink on canvas, 175 x 120 cm

Nicholas Grafia, Finding Black Chelsea, 2018, acrylics and Indian ink on canvas, 70 x 70 cm

“what fruit it bears”

4 Dec 2020 – 15 Jan 2021

Peres Projects, Berlin