“When I am an old woman I shall wear purple” – or so most of the models on Ari Seth Cohen’s blog, Advanced Style, seem to say. As for me, I hate purple. And I’ve been terrorized since childhood by Jenny Joseph’s 1961 poem that went on to promise that, besides puce, I would “wear terrible shirts” and that this would be some kind of liberation. I’m not advanced style-age yet, but I don’t think I’ll age wearing Pucci prints, ironic “Mrs Robinson hostess dressing,” or some of the other common options on offer – voluminous linen (hello Egg), or heavy-spectacled Edna Mode black. However much these could be perfect styles for someone else, they make me wonder, what do we expect from age and why is it anticipated as a change of a dress?

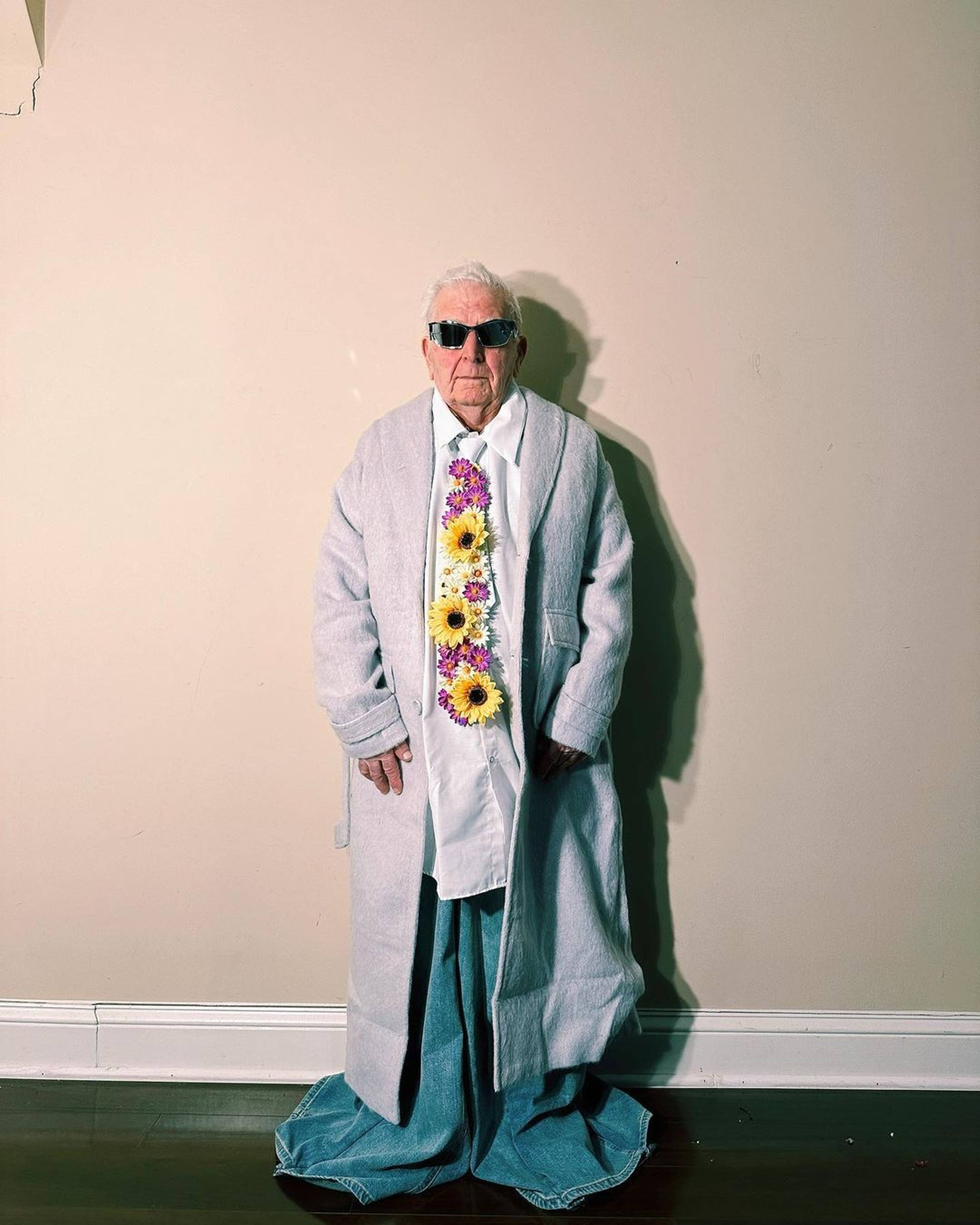

The centenarian supermodel, Iris Apfel, died earlier this year, in the era of the Eclectic Grandpa aesthetic. Recent aesthetics have also included Coastal Grandmother, Hot Aunt, Seaside Aunt, Mom n’ Dad jeans… which might make you think that “old” is in. Until you realize that these relatives are positioned around an implied grandchild/niece/nephew who borrows the look, the POV of each aesthetic still assuming the subject-position as young, just as Joseph’s poem was an anticipation of age spoken by someone younger. What does wanting to look old say about the posited “borrower”? Their models are less often “real” older people than some kind of ideal, as dreamy as cottagecore. While IRL moms only wear mom jeans ironically, and grandpas less often flannel than fleece, is this some kind of gesture of mourning for the ideal of family, or nostalgia for a mythic economic situation: a cherry-picked vision of the boomer boom of the mid twentieth century, stripped of its racism, sexism, and homophobia?

Qin Huilan modeling for Miu Miu FW 2024

Elsa, Ari Seth Cohen’s “Advanced style” blog, 2022

Margaret Howell’s 2024 lookbook finally featured older models, a decade after the British designer was criticized for showing her elegantly tailored utility wear, bought by a mostly middle aged (and older) demographic, on an exclusively young catwalk. At a Q&A with The Gentlewoman magazine in 2013 Howell said, “It is a bone of contention. But sometimes…working with the press, we have to keep them happy… Let’s say I’m not brave enough, I don’t have the courage.” Ethnically diverse models have been a fixture on the catwalk for some time, larger models are being given more space. It’s rarer, but now shows are sprinkled with older models too. This is usually a headliner, often a celeb (see Celine’s 2015 campaign with Joan Didion) but a number of designers including Lemaire and Batsheva regularly use older models in ways that don’t look “novelty.”

While fantasies of fashionable eccentricity gather around models in their seventies, eighties and beyond, middle-aged models are scarcer, as the high-profile recent fiftieth birthdays of the 1990s supermodels has highlighted. But, even as fifty becomes the new forty, and sixty the new fifty, there’s still a time when women in particular start to notice fashion no longer notices them. Women, as Susan Sontag wrote in her 1972 essay, “The Double Standard of Aging,” “are old as soon as they are no longer very young,” and aging, “is a crisis that never exhausts itself, because the anxiety is never really used up.” Anxiety is – as Lauren Berlant wrote in The Female Complaint (2008), quoting Jaqueline Rose – “the core affect of femininity, which operates under an imperative never to fail to stop working on itself.”

Like “outrageous,” “fabulous,” and “flamboyant,” “eccentric” is an adjective fashion-applied to presentations that don’t fit the heterosexual standard, indicating that aging is also a queer state.

This work is not always a drag. With age, conventions of gender come into question, the gender in question mostly being – to paraphrase Luce Irigaray – that gender which is not one: female. As men’s faces get softer, women’s more angular, and both complicate into folds and wrinkles, aging can offer the chance to rework codes. This play is serious. “Gender is a language, and it could be fun to play with if there wasn’t so much power and coercion attached to it,” said sharp-dressing middle-aged transitioner, McKenzie Wark, in a 2023 interview with the online magazine A Shade Colder.

But why are old people so often expected to appear eccentric? Like “outrageous,” “fabulous,” and “flamboyant,” “eccentric” is an adjective fashion-applied to presentations that don’t fit the heterosexual standard, indicating that aging is also a queer state. It is also an adjective used for older dressers that seems to take the place of concepts like “beautiful” and, particularly, “sexy,” which is a place few brands want to go. “Gender,” Wark goes on, “is, after all, also closely linked to sexuality.” Sixtysomething model Alex Bruni recently starred in a campaign for Bluebella – but as part of a body positivity drive that featured only models who could be considered “unusual” choices for a lingerie brand. Brands are always (also) about selling, and it’s no surprise that acceptance comes on commercial terms. As the recent decomplexification of the menopause shows, in the age of data capitalism, for every newly visible demographic, there’s a company trying to sell them vagina serum. The real push for age acceptance in fashion has, as with other forms of body inclusivity, come from places considered “eccentric” – literally on the edges – not from the heart of the industry but from blogs, from personal Instagrams, from individuals. This is the kind of eccentricity that counts.

Maggie Smith, Loewe SS 2024 campaign

Age visibility – like any expansion in visibility – involves more than diversity redress. The more older people are fashion-invisible, the easier it is to avoid thinking about aging. Besides its inevitable eventual associations with death, thinking about age might involve thinking about how, the older you get, the more likely you are to be rendered literally “eccentric” – marginalized, economically and socially. To show older people in fashion demands the creation of fashion stories for these bodies. Do fashion shoots play with the stereotypes, or avoid them, or invert them? Are older catwalk models dressed in workwear or leisurewear (and what sort)? Do they show older people in the country or the city, in tea shops or in bars, with family or friends (their own age or not?), or alone? Are they lovers, are they workers? Are they rich or poor? How we are able to think about dressing is, as always, a question of how we can think about living, and “normalize” aging means normalizing so much more. It really is about time.

As for Jenny Joseph, however much she was writing from a more culturally repressive age, looking forward to age as an escape from the pressures of the present is a deferral of confronting those pressures today. If you like purple, wear it now.