In 2000, I was in New York, where I still partly live. Gelitin had one of the artist residencies on the ninety-first floor of World Trade Center 1 offered by the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council. All four members of the collective were there when they hatched the idea of attaching a balcony to the out- side of WTC 1, directly facing the Millennium Hilton.

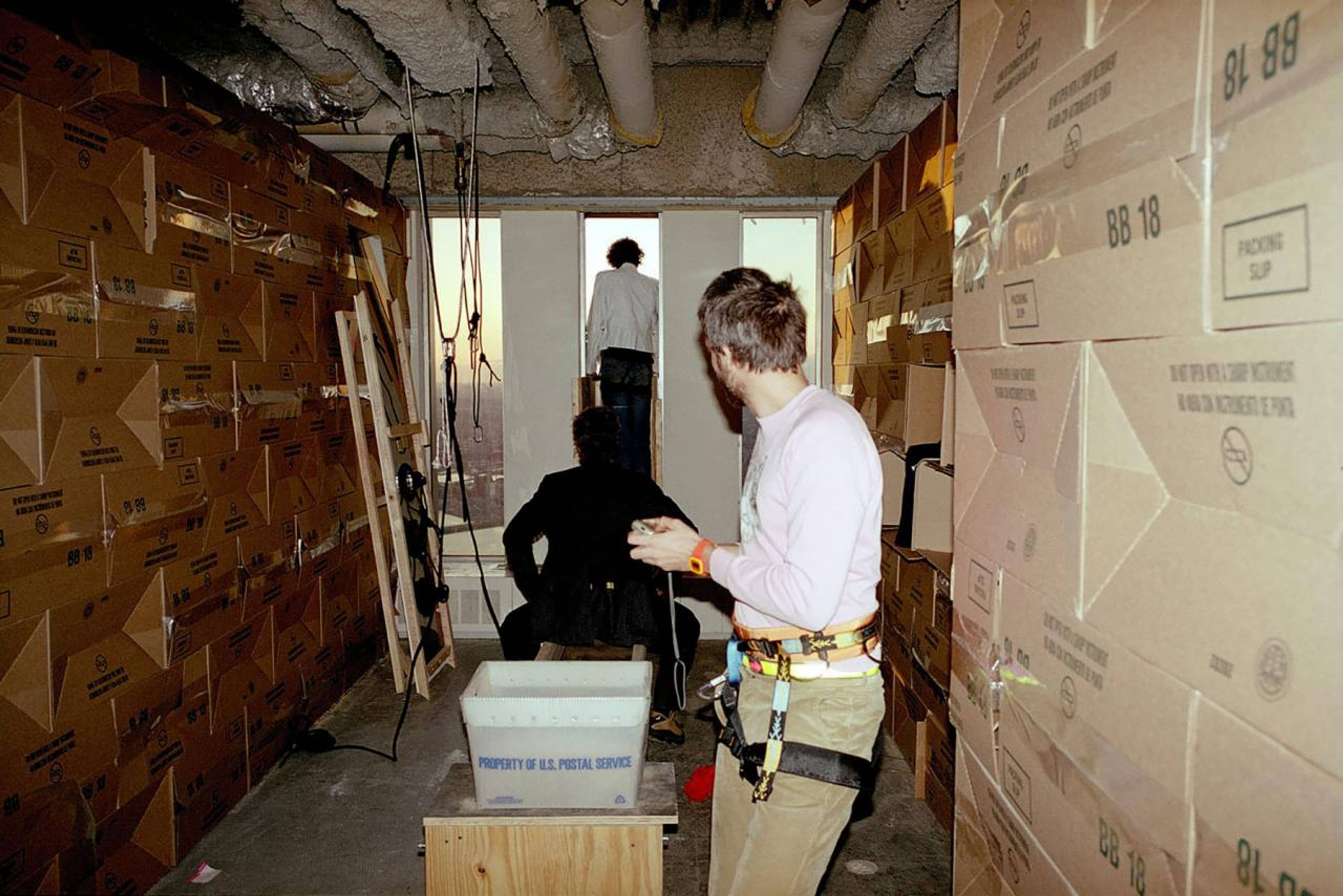

I visited their studio while the project was underway in 2000, and I remember being almost unable to move because they had stacked dozens of cardboard boxes from floor to ceiling inside a basic wooden room-in-a-room that they had constructed during their time there. The effect was that a section of the windows facing out toward Manhattan was obstructed by the boxes and interior structure. When one entered the studio space, there was a small area that was completely closed off, a corner of the room that was camouflaged by the boxes. The idea was that someone familiar with the group could easily assume that the “art” they were working on was the boxes, or in the boxes, or some sort of combination of the two. The reality was that the actual project they were working on was behind all of this and well hidden.

I knew that they were planning to open a window in order to attach a balcony to the outside of the studio, but I didn’t quite understand how. One of the obstacles to over- come was that one could not open the windows on the ninety-first floor. In fact, it was illegal to open any of the building’s windows, for obvious reasons. Gelitin had to devise a way to carve out the putty that surrounded the windowpanes, and carefully detach the glass. Then they needed to construct a balcony that could support the weight of at least one person. Very early in the morning on a Sunday in March, the partners of the four Gelitin boys, myself, and few other friends were invited to a hotel room at the Millennium Hilton rented by Gelitin’s gallerist at that time, Leo Koenig. The gallery had rented a room facing the east side of WTC 1, and also commissioned a helicopter and photographer to document the work.

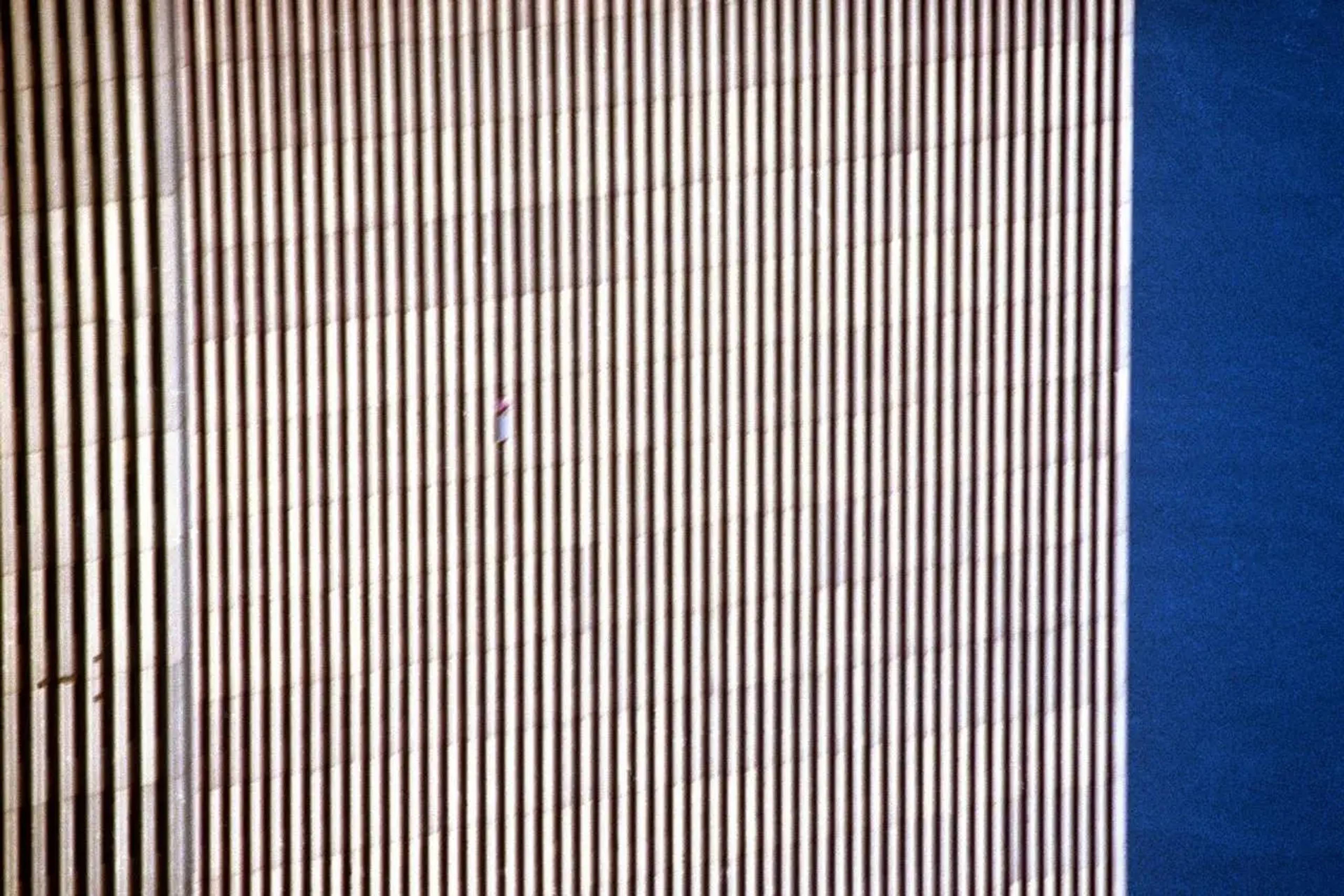

At daybreak, we all watched in the throes of anticipation and fear as a one of the windows on the facade of WTC 1 opened and a small wooden balcony, something like a cantilever, was attached to it. One by one, wearing angel wings and brightly colored T-shirts, each of the four Gelitin boys made their way onto the balcony. So that we could recognize them from afar, each member wore a different color. I know that many in the press – Gelitin has been incredibly secretive about the project – believe that The B-Thing never happened, which is why I’m talking about it now. I was there and stood in awe at the sight of tiny human figures with wings standing, brie y, on a balcony attached to the facade of this gigantic skyscraper. The sight was so beautiful, fragile and heroic at once. They appeared, across the street, as tiny blips among the windows and reflections.

Oddly enough, the helicopter and hotel photos were meant to serve as exhibition material for Gelitin’s show at Leo Koenig Gallery the following year. Whether by coincidence or some unnameable cosmic force, the opening day of the exhibition was 11 September 2001. Tobias Urban from Gelitin was staying with us when I received a call from my brother in Athens that a plane had crashed into one of the World Trade Center towers. In disbelief, Tobias, my partner, and I all went to the rooftop of our building at the time and watched as the second plane crashed into the second tower, and the gigantic structure burst into flames and eventually collapsed.

Looking back now, the beauty and innocence of The B-Thing is stronger than ever, shrouded in the horror of that destructive moment in 2001. What is more remarkable to me, even now, some twenty years later, is that the true documentation of this project is much more than the amazing book that was released in 2001. The fact that this project really took place can only be confirmed by those who were either part of the project or among the few that witnessed it. The B-Thing is still one of my favorite works of art and being reminded of it in the context of the recent history of Lower Manhattan – and particularly those events that changed the US in a major way – makes it all the more powerful. The work was so playful and intelligent in a Gelitin way. The boys used their residency to push the parameters of the site itself, reflecting the conditions of power, money, and the icons of New York at the time.

– As told to Colin Lang

___

This text was originally published in Spike #63 – The NYC Issue. You can buy your copy in our online shop.