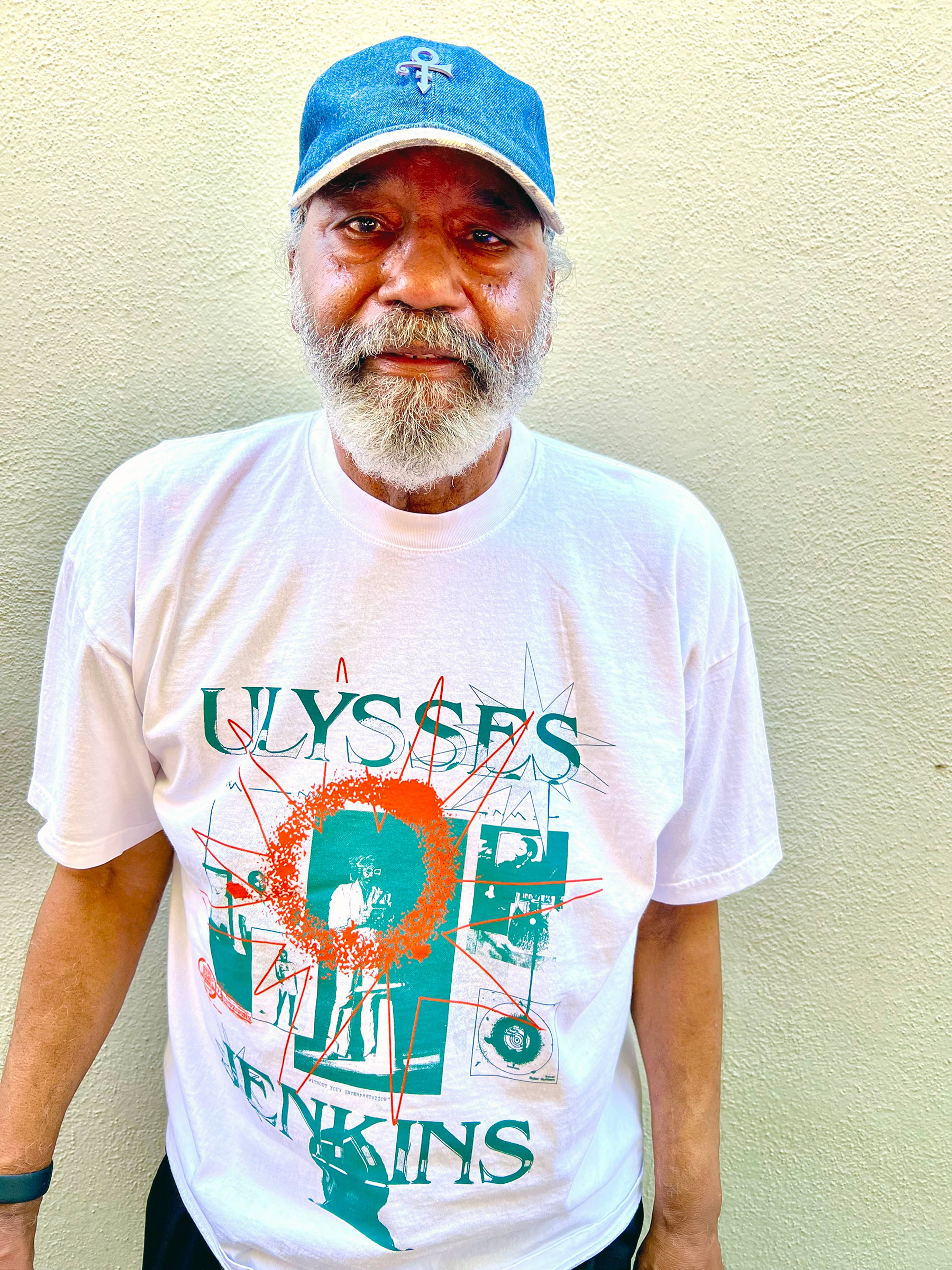

A half century into a career at the forefront of video art generally and Black experimentalism specifically, Ulysses Jenkins first retrospective, “Without Your Interpretation,” brings his doggerel, ritual-rich, and communitarian opus to a European public at the Julia Stoschek Foundation, Berlin. Here, the film polymath speaks to ASCO co-founder and fellow Los Angeleno Harry Gamboa Jr. about linking technological liberation to self-love, LA’s ethos of inclusion, and finding humor in the struggle against art’s absurd ideals.

Harry Gamboa Jr. : We met at some point in the 1970s. You were involved in performance art, and I was doing the same thing. My approach was primarily photo-based, whereas you worked with music and your own body, dealing with identity at a moment when so many different things were happening, as the 20th century was coming to a close. What was motivating your work at that time?

Ulysses Jenkins: I was trying to deal with issues that had to do with stereotypes of African Americans, and how those stereotypes were reflected through depictions of Black people in Western art. I started out as a painter, and going back into history of painting, all I could find was that Black people were painted as servants. That most African Americans were painted in servitude in a Eurocentric notion of art had translated into filmmaking, which I picked up on when I was in college, when I started making works like Two-Zone Transfer (1979), Momentous Occasions: Charles White (1977–82), and Mass of Images (1978).

We both emerged from the Vietnam War era, amid all sorts of technological change, and almost overnight, it became a bit more possible to create things independently, to express some form of self-love, as opposed to having to dwell on darker things. You presented yourself as an example of a liberated creativity, which seemed to be at the core of what you were up to.

I was influenced by the notion of independent films, but also I was introduced to the Portapak camera. I got into video, and I was really fascinated by the notion that you could actually record video independently.

Of course, the batteries probably weighed as much as a Volkswagen, which were connected to the cameras by a cable, but even then, it was possible to be quite mobile. Previously, the only access to such technology was in the hands of the police. Suddenly, the public could use it free of the constraints of corporate power and police power, artists could take some control of the medium, and you were at the forefront of that.

Still from Ulysses Jenkins, Remnants of the Watts Festival, 1972–73, compiled in 1980, video, 56 min., b/w, sound. Courtesy: the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix

I was fortunate enough to attend a workshop on the boardwalk in Venice Beach, where I was painting a mural at the time. A good friend of mine, Michael Zingales, who was also a painter, introduced me to these two or three guys from New York who had come to Venice with a Portapak. They were having workshops and renting out the equipment for people to use, which is how they were going to pay for it. That’s how I got started.

Simultaneously, there was this thing called Public Access Television at the cable station. It was in Santa Monica where I was able to start getting my work screened to an alternative community, which is what the notion of public access was really about.

The thing about public access is that it was directly connected through cable, which meant it went directly into living rooms. People in Santa Monica, which was demographically pretty upper class, high income, and predominantly white, otherwise would not have been introduced to any groundbreaking, contemporary avant-garde art created by African Americans, Chicanos, or anyone else. In a way, this kind of distribution depended on subscription. But the particular networks allowed you to be viewed in Santa Monica, in Malibu, probably in the South Bay, rich places that never would have been introduced to something like your work. Back then, the other option was regular commercial television, which either completely excluded African Americans and Chicanos or completely misinformed people through negative stereotypes.

Right. Right. The video I got my start with on public access TV was Remnants of the Watts Festival (1972–73, compiled 1980), which has a section where I interview a Latina who makes a really great commentary, based upon her experience of being included in the community of Watts, about how great she felt that event was. So I actually started out working with the notion of inclusion, because that workshop I’m talking about was on the boardwalk in Venice, and if you know anything about the boardwalk in Venice, you see everybody.

When I started making my artwork, I was saying, “Why do we have segregated art constituencies when, in society, especially in LA, you’re going to run into everybody and every culture?”

I think the Venice boardwalk was, in a way, an advanced element of what Los Angeles would become. Again, we’re talking about everything that happened in the early 80s or the early 90s, when there was so much racial violence. The city has been transformed since then: there are now over a hundred languages spoken in Los Angeles, and there are so many cultures, and a giant demographic shift was taking place. All of your efforts led toward the acceptance of others, not only inclusion, but really embracing people, it seemed like. I always had that feeling from you, that you were welcoming everybody, and this way, we could move forward in a peaceful manner and appreciate each other’s cultures.

I happened to grow up on what was considered the west side of LA, I went to Hamilton high school, 1961 through 1963. There were like twenty-five black students in the whole campus. Integration was the cultural dynamic of those days. Unfortunately, a lot of Black kids these days, they hear about the term integration, but they’ve never lived it. For our generation, it was something that, if it didn’t happen immediately, you eventually ran into it. Learning how to be around and live around other cultures was certainly a thing that I experienced, so that when I started making my artwork, I was saying, “Why do we have segregated art constituencies when, in society, especially in LA, you’re going to run into everybody and every culture?”

Utilizing video was so empowering, as the actual technology wasn’t exactly readily accessible, and it did require a little bit of training, and editing. It was kind of restrictive, because instead of having it all on your phone, like we do now, everything required separate components for every single step of producing video, and so completing anything really required an effort and an expertise. You found yourself committed to moving forward in this medium, because at that point, it would have been brand new.

After having my own independent experiences with video, when I got to grad school, I made what has become one of my major videos, Two-Zone Transfer . To speak to what you’re talking about, I had to edit that particular piece in the video studios at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). I was only able to get in by getting a password from Gary Lloyd, who was one of my professors at Otis and was teaching at the time at UCLA. Just a quick little number about that: One day, while I was living in Venice, he called me at about 11:30 and, “You got to get in there by 12 o’clock. Here’s the combination.” So I go in and locked the door. People are screaming and yelling at me, “Who are you? Let me in!” But I never did open the door, and I got my project edited.

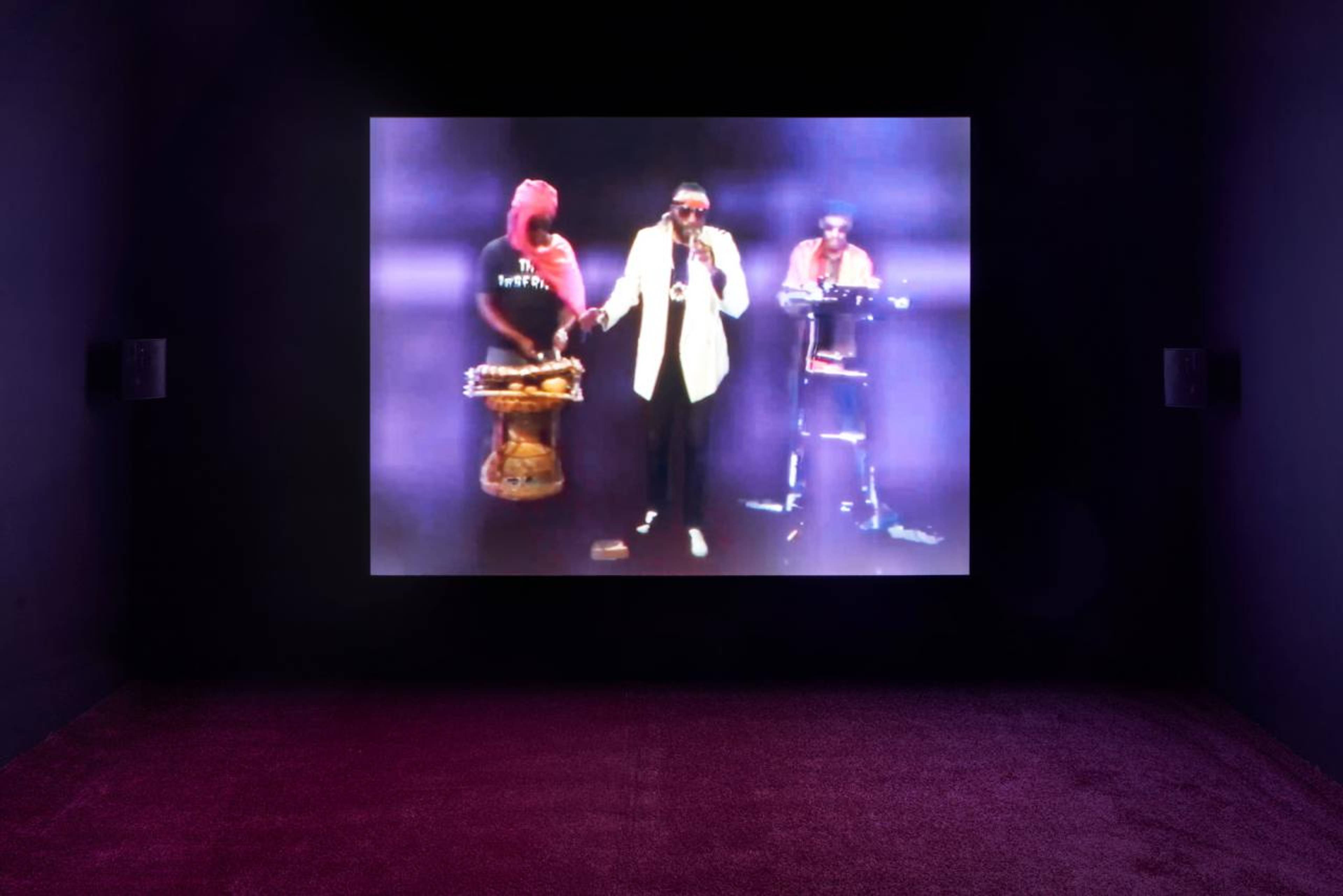

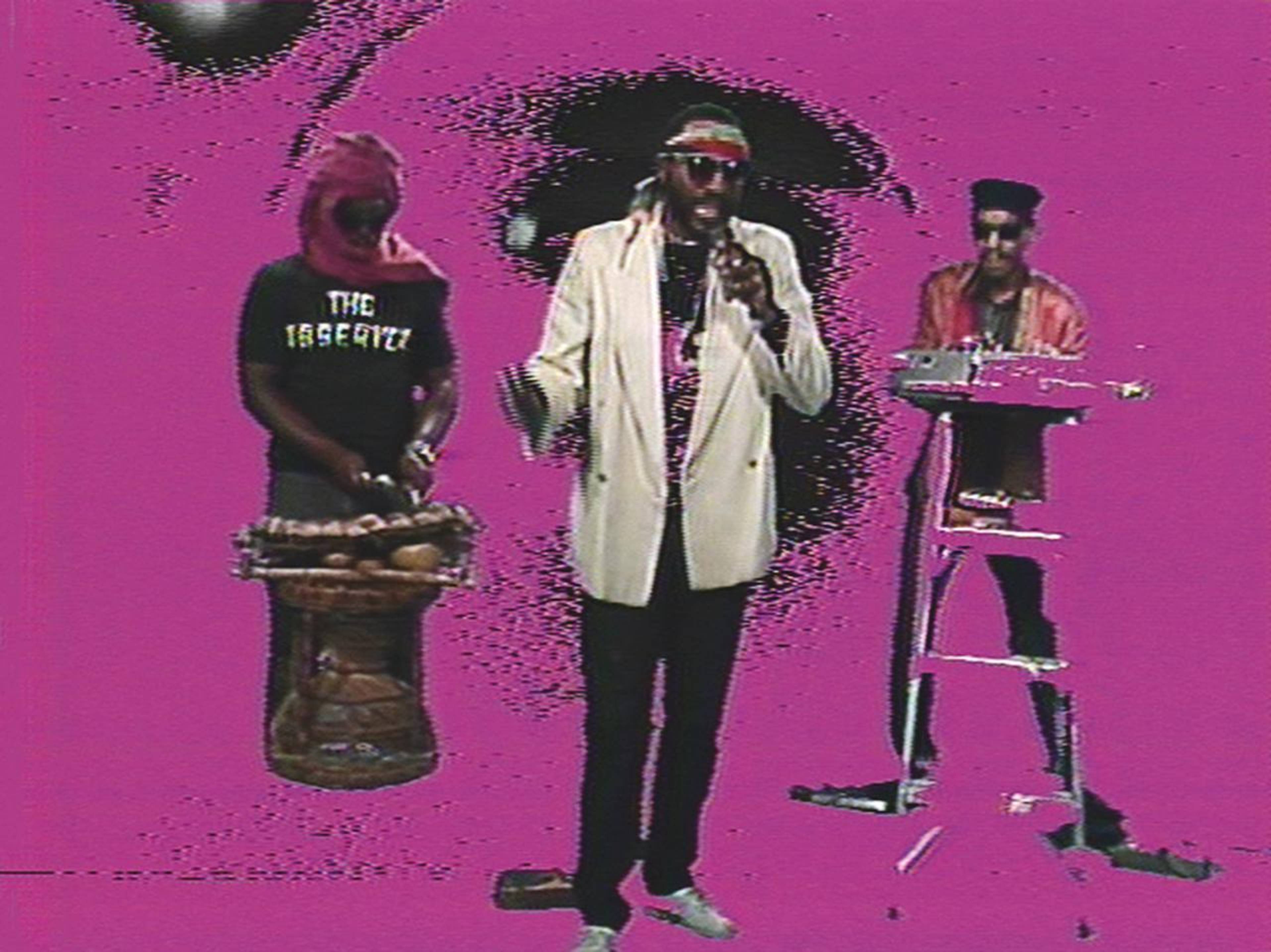

Still from Ulysses Jenkins, Peace and Anwar Sadat, 1985. Installation view, JSF Berlin, 2023. Photo: Alwin Lay

Left: Still from Ulysses Jenkins, Two-Zone Transfer, 1979; right: Ulysses Jenkins, Two-Zone Transfer Altar, 1979. Installation view, JSF Berlin, 2023. Photo: Alwin Lay

I’m kind of familiar too with barricade techniques to get a project done, always looking at the escape hatch. Part of what you were also doing during this period was to organize people into larger events. There was more support for art in that era, the National Endowment for the Arts was still providing individual fellowships. There was more of an interest then in some of the people who were very visibly connected to the city, and maybe even the state. It also took quite an adjustment for you to not only move forward as an artist, but also as a professional and as an educator, before you wound up at the University of California, Irvine (UC Irvine). How were you able to generate all that energy and maintain that focus, uninterruptedly making your work through all the professional development?

At a certain point, I was an artist in residence for the California Arts Council. I was fortunate enough to be selected as one of the artists for their multiculturalism program, and I think we had a lot to do with the history that you’re talking about. The people I worked with in that program, like my manager Lucero Ariano and Josephine Talamantez, don’t get enough credit for the work that they’ve done to promote multiculturalism.

I got selected to go to a conference in 1985 or 86 in Washington, DC. It was the beginning of a whole notion of multiculturalism on a national arts basis, and I was amazed at how far ahead California was in that kind of a practice.

To make a long story short, my residency really helped me to be a part of the forefront of a movement at that time, as the NEA (National Endowment for the Arts) started paying more attention to artists of color. I also saw all the sudden that Eurocentric artists wanted to work with artists of color, because that’s where the money was. Maybe these things seem minuscule to some people, but they were very important aspects of how art has been transformed into what it has become. Today, younger artists can jump right into this thing called the art world, which is very different from the circumstances that we had to experience.

It’s kind of difficult to explain but, to go to back to what we said earlier, during that period the media was very exclusive and very rarely focused on the creative contributions of African Americans and Chicanos, and to have any kind of media attention at all was a great feat. Major newspapers either made or ruined careers, and to be able to enter into dialogue with mainstream media, the arts, local news, and government required a great skill in social adaptation. Not only were you and I required to adapt, but in the process, we also changed the people we were confronting, which could earn us at least a little bit of support, essentially seed money, to then create works that might receive greater funding.

What you’re talking about here is transformation. The main thing that it was hard to get my students to understand is that the the art world is based on Eurocentric ideals. When you’re not addressing their ideals, getting people to actually pay attention to what you’re trying to say becomes one of the first and hardest parts for young artists in particular to understand. There was an artist who contacted me after my retrospective (“Ulysses Jenkins: Without Your Interpretation”), who wanted to meet with me. She wanted to introduce the pathos of being humans, that everybody has as an issue in their lives. It may have a different shade of color or a different rhythm, but everybody has it. You see it in these movies coming out today with people of color that are winning awards, that’s the improvement that we’ve all been waiting for.

You have to come to that place where you find humor in the struggle. Because it is going to be a struggle, based on what our forebears had to endure and the way that we want change.

Whenever we’ve gotten together, we always seem to be laughing a little bit, as it does require a bit of humor to get through some of these more absurd ideals, these restrictions, which were established hundreds of years ago and are reinforced up until the present. Whenever you come across a whole new crop of people that might be embedded in this, it’s like teaching people how to make fire all over again.

I really appreciate what you were just saying, Harry, because the thing is, you have to come to that place where you find humor in the struggle. Because it is going to be a struggle, based on what our forebears had to endure and the way that we want change. Then again, there’s this whole group of people who, unfortunately, only want to go backward in time.

They’re so afraid that they’re going to lose something, which will continue until they start to understand that it comes down to being able to share, that there’s a season for everything, that there should be opportunities for everybody.

Your exhibition at the Hammer Museum, was a great gift to not only the city of Los Angeles and to your legacy, but also now to Germany and wider Europe, as an introduction to a global understanding of your work, your effort, your presence, a persistence of vision.

I really appreciate that commentary, especially coming from you! The show in Berlin had an enormous crowd at the opening. I was told that it was 17 degrees Fahrenheit outside that night.

I’ve been to Germany before, so that sounds almost like summertime. I’d also like to mention that it was a great honor and great fun to work with you to create the video No Supper (1987) long ago, along with members of ASCO, Humberto Sandoval, Barbara Carrasco, and my son Diego Gamboa. It was quite amazing, because it also was for public access, and so spontaneous. I mean, it was as though a stopwatch had been presented to me, and it was almost shot in real time and was basically unedited. It’s how my process is, your process as well, having to be super agile, utilizing all the sensibilities to make things work and to keep up the momentum. It’s really great talking to you today, because it feels like you’ve never missed a beat and, and still keeping up in steps.

It was an honor for me to work with you, too, Harry. In terms of your own personal history, I thought I knew what social change and improvisation were until I worked with you.

Still from Ulysses Jenkins, Mass of Images, 1978, video, 4 min., b/w, sound. Courtesy: the artist and Electronic Arts Intermix

Still from Ulysses Jenkins, Peace and Anwar Sadat, 1985, 22 min, color, sound. Courtesy: the artist

Ulysses Jenkins, Centinela Valley Juvenile Diversion Mural Project, Boulevard Market, Lennox, CA, n.d., mural documentation, photograph. Courtesy: the artist

___

“Ulysses Jenkins: Without Your Interpretation”

Julia Stoschek Foundation, Berlin

11 Feb – 30 Jul 2023