It begins with a kiss. Not a polite kiss, nor one soft and yielding, but the humid, self-obliterating kind – the heavy kiss of heavy tipplers at the end of a long night. In the recent paintings of American artist Nicole Eisenman, these ponderous embraces have grown from an occasional motif in her work to a full-blown theme. They show up in the interlocked profiles of Springtime Kiss (2011), all pink-nosed passion surrounded by a bluish jubilee of piney landscape, and in the tender, crapulent Sloppy Bar Room Kiss (2011), where the lovers limply lock lips before a few empty bottles with their heads slumped on the barroom table. They kiss languidly, wearily, with total surrender.

Nicole Eisenman’s kissers join a pantheon of tongue jockeys, from Edvard Munch’s 1897 Kiss, where two heads freakishly fuse into one beige blob, to Brancusi’s smooching masonry. But they also perform an almost emblematic function for her work. Eisenman’s sloppy kisses mark a couple of her preoccupations: scenes of conviviality that border (or proceed straight into) the pitiful or barbaric and instances of deep, occasionally unseemly intimacy. In fact, one could view Eisenman’s whole oeuvre as a sustained exercise in closing gaps – between art movements, between figures, between pathos and horseplay, dirty jokes and serious politics.

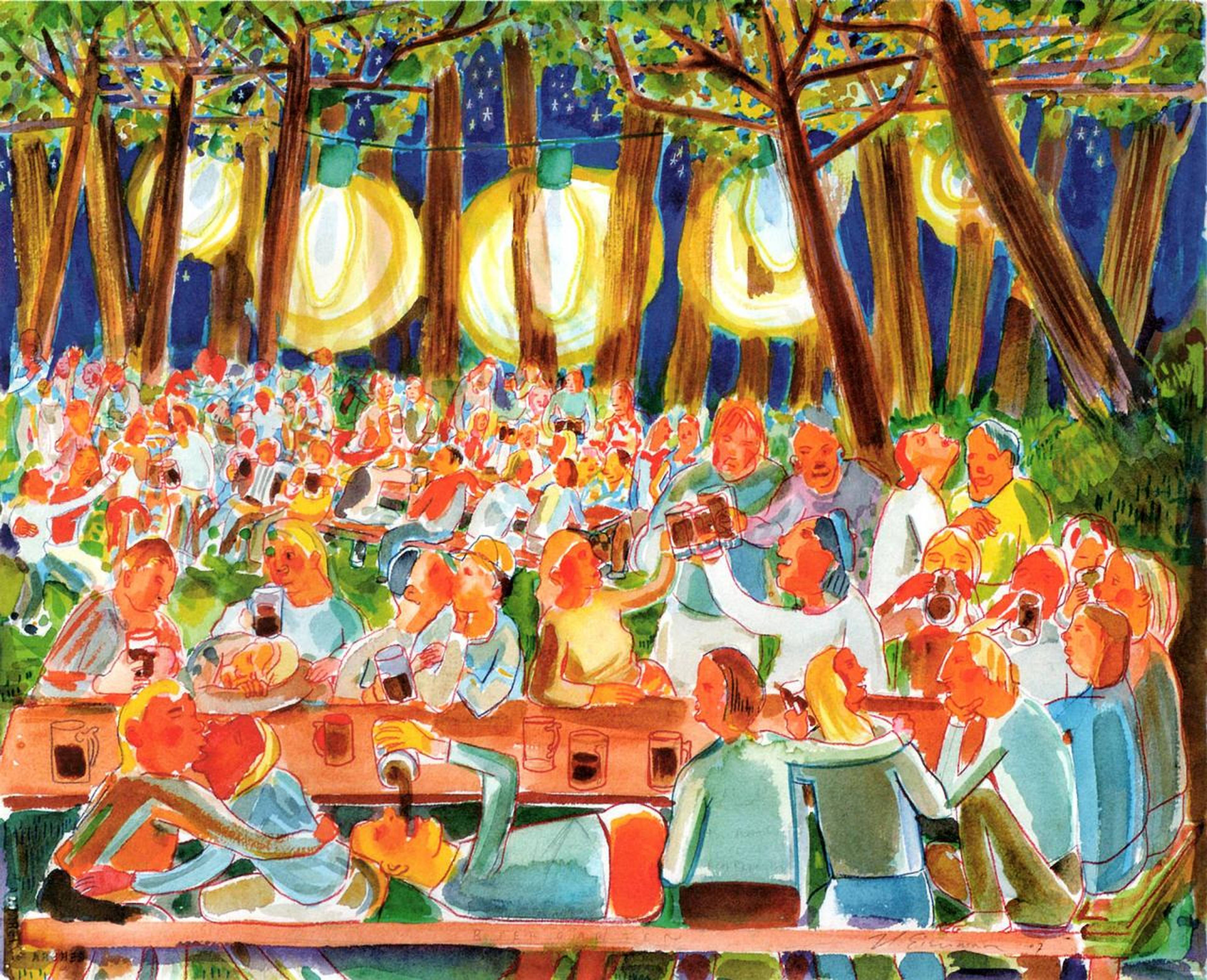

Nicole Eisenman, Untitled, 2007, watercolor on paper. Courtesy: Leo Koenig, Inc., New York

Yet this image of Eisenman is plainly at odds with her rap as a “bad girl” painter, a reputation she has spent decades outpacing. The two exhibitions with which she established herself in the art scene of the 90s – Marcia Tucker’s “Bad Girls,” at the New Museum in New York and the Los Angeles Wight Gallery in 1994, and the 1993–94 “Bad Girls” at the ICA in London and the CCA Glasgow – also put a name to Eisenman’s pigeonhole, one that supposedly explains the ethos behind images like her sardonic, cartoonish figures engaged in violent or erotic play and her apocalyptic vision of the Whitney in ruins – her contribution to the 1995 Whitney Biennial. Never mind the trivializing title, “Bad Girls” also characterized the feminism of an entire generation of women artists (among them Sue Williams, Collier Schor, Helen Chadwick, Zoe Leonard, and Nicola Tyson) as mere obstreperous misbehavior. Certain of Eisenman’s efforts since then, such as the periodic curatorial initiative Ridykeulous, cofounded with artist A.L. Steiner in 2005, seem like direct responses to the reductiveness of “Bad Girls”; Ridykeulous manages at once to perform a burlesque of lesbian-feminist subculture and provide real occasions for discussions about identity, sexuality, and activism. In her own work, Eisenman’s self-distancing from her “bad girl” image has been gradual and thoughtful, as she has steadily backed off the wisecracks in her paintings in the 90s while laboring to express a colossal art-historical appetite through her references. Descriptions of her work often cite Expressionism and Impressionism, along with Surrealism, Neoclassicism, WPA murals, East Village underground comics, horror films, folk art, pornography, Beckman, Dix, Grosz, Dürer, Hogarth, Titian, Délacroix, Matisse, Picasso, and Norman Rockwell.

There is something defensive in this screed of references – as though a woman painter, especially one who has been called a “bad girl,” must constantly affirm the pedigree of her canvases. But that also helps account for Eisenman’s eclectic sensibility, which lately extends not only to the content of her paintings, but also to her chosen media. In 2011, the barroom kissers appeared in a two-color lithograph published by Jungle Press Editions. The lithograph is one in a series of prints produced during the most recent phase of Eisenman’s work. In August 2011, Eisenman locked her paints in a trunk, repainted her studio, and embarked on a long season making works on paper and prints. The fruits of this labor were exhibited in the spring of 2012 in two ambitious exhibitions: one at Leo Koenig Inc. in New York and the other, concurrently, in the Whitney Biennial.

All images: Nicole Eisenman, Untitled, 2012, monotype on paper, c. 59 x 45 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Leo Koenig, Inc., New York

Prints, of course, are a kind of kissing too – two surfaces pressing against each other, indulging in such a heavy exchange of fluids that it results in reproduction. The majority of Eisenman’s prints, however, do not carry this process to its logical end in reproducibility. Rather, they are monotypes: one-of-a-kind transfers to which Eisenman occasionally adds collaged materials or additional painted details. A number of the prints feature heads: a chocolate-brown bald man besieged by cigars that seek to plug his every orifice, a vermillion lady with a starburst heart and an aura of Munch-like outlines, and a set of Eisenman’s cryers, who made earlier appearances in her paintings, with their eyes discharging brackish runnels that pool around the bottom of the frame or hang like stalactites.

In addition to these faces, Eisenman’s prints present a procession of enigmatic scenes: a tiny cowboy perched atop a smug gorilla, a troupe of mopey children saluted by a gutter drunk, the specter of Abraham Lincoln with fur paws protruding from his cuffs, a fluorescent rendition of Van Gogh’s Portrait of Joseph Roulin. There are echoes of Picabia’s baroque painted figures and Picasso’s last self-portrait, goggle-eyed and green-faced. There are also gynecologist’s-eye-views of zaftig nudes, one self-stimulating before a brilliant sunrise, another holding herself open before a ball of twine and twigs.

Her repertoire is filled with bodies opening onto other bodies or seized in moments of fantastic or freakish transformation.

This hole qua portal both intensifies and debases the psychological portals offered by Eisenman’s portraits, debases them by wrenching them from the space of abstract contemplation back into bodily matters of insides and outsides, surfaces and interiors – matters which are, in fact, at the heart of Eisenman’s prints. The monotype, created by laying pigment on a smooth surface and then transferring the image to a sheet of paper, reverses the process of painting, turning the image inside-out like a pocket. Underpainting becomes surface detail, as the foundation or “interior” of the painting on the plate becomes the surface layer of the print.

This inversion corresponds with longstanding figural impulses in Eisenman’s work. Her repertoire is filled with bodies opening onto other bodies or seized in moments of fantastic or freakish transformation: from the 1999 Man Cloud, where the tangling male nudes of Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina turn peaceful and float on air, to the 2012 monotype where a man’s profile sits eye-to-nipple with a quasi-headless, hairy, giant-breasted little woman. “Determining what constitutes a body in art is wide open,” explained Eisenman in an interview with Lynne Tillman. “Art doesn’t eat and excrete and isn’t restricted by needs like a glandular system or kidneys. In art, a mattress with two melons is a perfectly acceptable body.”

Monstrous, incomplete, excessive, or caricatured, Eisenman’s bodies correspond to something like Mikhail Bakhtin’s grotesque. For Bakhtin, the grotesque body is exaggerated precisely at the spots where it projects or opens onto the world – the genitals, the nose, and the mouth. Because of this propensity to transgress its own borders, the grotesque body is constantly in the process of forming itself through this ambiguous relation to the outside world. The stakes of the grotesque body, like the carnival with which it is associated, are not only aesthetic. Just as the carnival inverts the spectacle of political hierarchies, the grotesque celebrates the underside of our identities, subverting all our spiritual or intellectual tendencies to a messy, excessive, porous body. This body cannot be easily regulated – not because it resists the world, but because it seems to merge with it in unexpected ways, generating something like a collaborative body. Eisenman’s works hang shoulder to shoulder, an image of an eclectic collective formed by a most indecorous kiss.

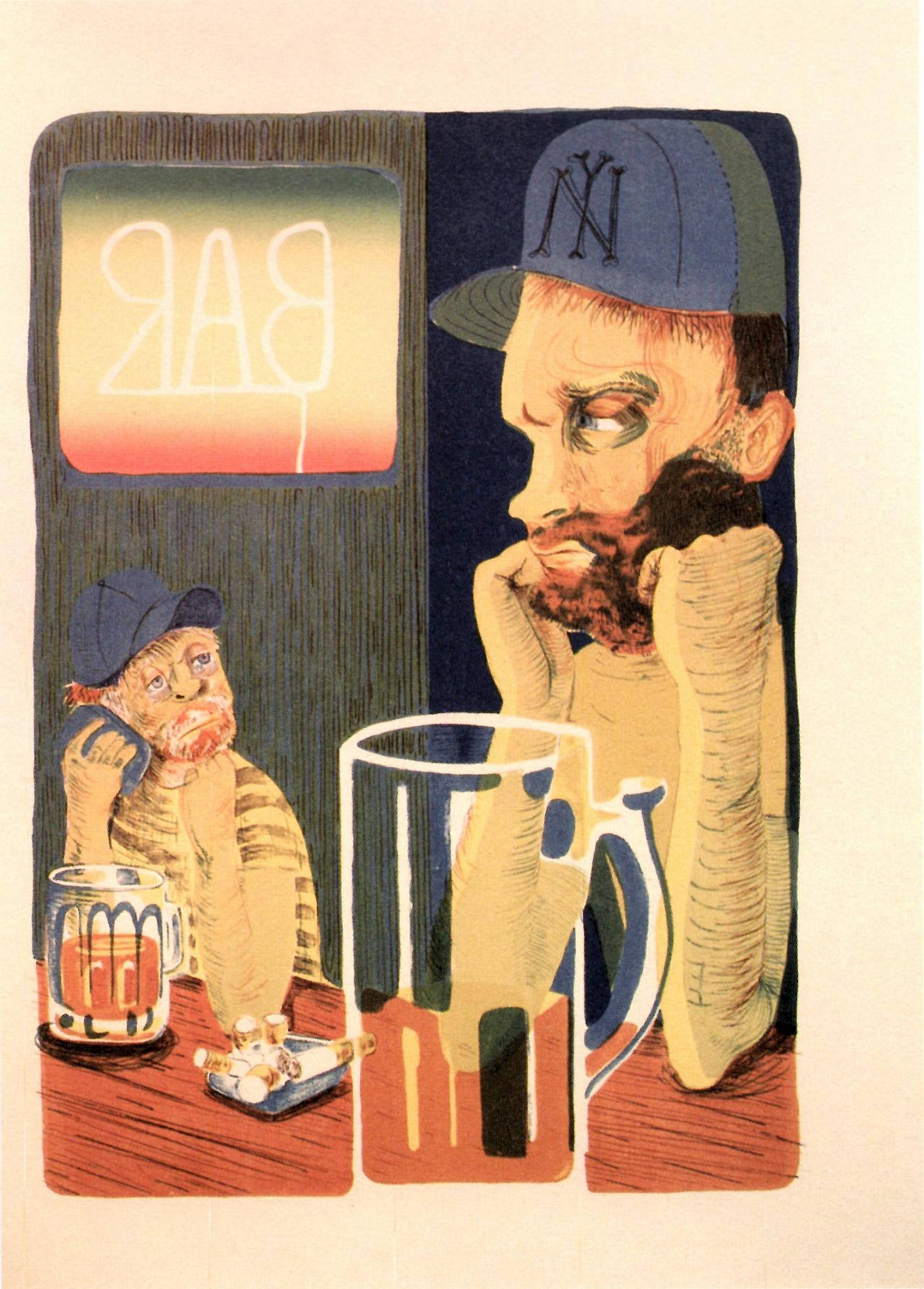

Nicole Eisenman, Bar, 2012, nine-color lithograph, 78 x 59 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Leo Koenig, Inc., New York

___

“What Happened”

Museum Brandhorst, Munich

24 Mar – 10 Sep 2023

“What Happened”

Whitechapel Gallery, London

11 Oct 2023 – 14 Jan 2024