The general portrayal of Amy Sillman’s work is not exempt from the rather annoying insistence on painting as “work between figuration and abstraction.” Painting, however, should manifest a gateway, as Sillman insightfully reassures us in her solo exhibition in Bern, where physical space and linear time are suspended, and all circular possibilities are made available.

It is a poignant metaphor both for Sillman’s understanding of her artistic process and for the our view onto such a large selection of her work. Visitors are given the opportunity to discover their own journey, to walk slowly, to look, to observe, to skip a room, to remember details in the manner of the similar or the crooked, to observe anew, to move backward and then forward again – all key to accessing Sillman’s complex and fragmentary idea of the experiential unity of space and painting.

View of “Oh, Clock!,” Kunstmuseum Bern, 2024. © Kunstmuseum Bern. Photo: Rolf Siegenthaler

Take, for example, the reinstallation of Untitled (Frieze for Venice), which was originally shown at the 59th Biennale in 2022. The walls are divided into two registers, not unlike traditional “old masterly” history painting. The upper row is a series of medium-sized, horizontal, mixed-media works on paper, realized during the 2020 lockdown and installed here in rhythmic syncopation along a wall-painted stripe of electric blue. In the main register below, larger silkscreen works on paper – sometimes supplemented by painterly gestures – replicate parts of and whole images from the upper frieze, juxtaposed or overlapping in a controlled anarchy. Once the coding is grasped, the viewer’s experience becomes circular and inspiringly mnemonic: The forms and signs are repeated, yes, but in different spatial and chromatic scales. The feminist irony in the treatment of a genre held for centuries under exclusive male contract is compounded by a 2011 painting, Mouth, hanging alone in the same room. An inventive and hasty caricature of hybrid human genitalia, the vagina becomes a grimace from which a penis and breast-shaped testicles hang like a silent balloon from a comic strip. In order to maintain the entire space’s integrated apocalypse, the wall on which Mouth hangs is painted blue only in the lower register, diametrically mirroring the other walls.

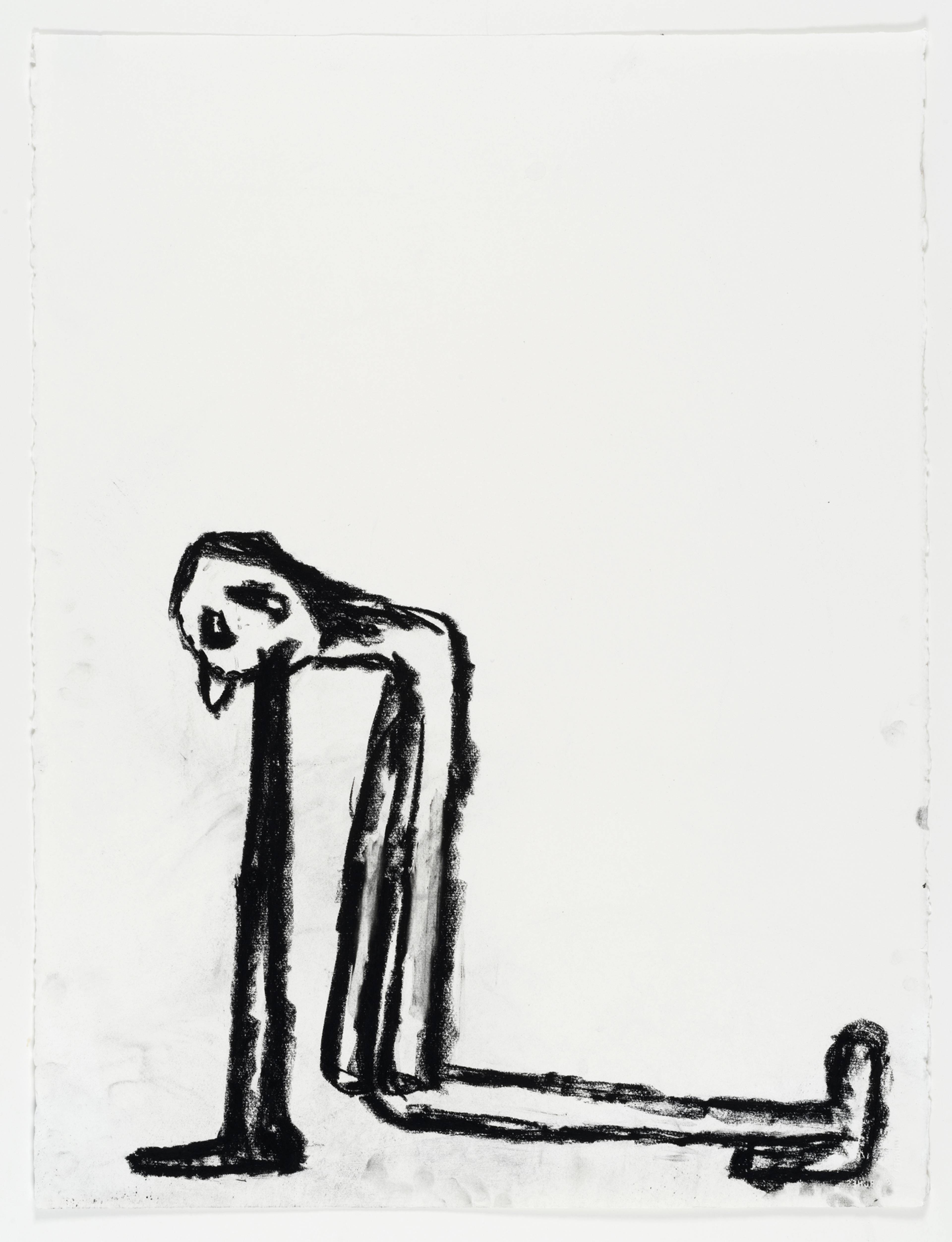

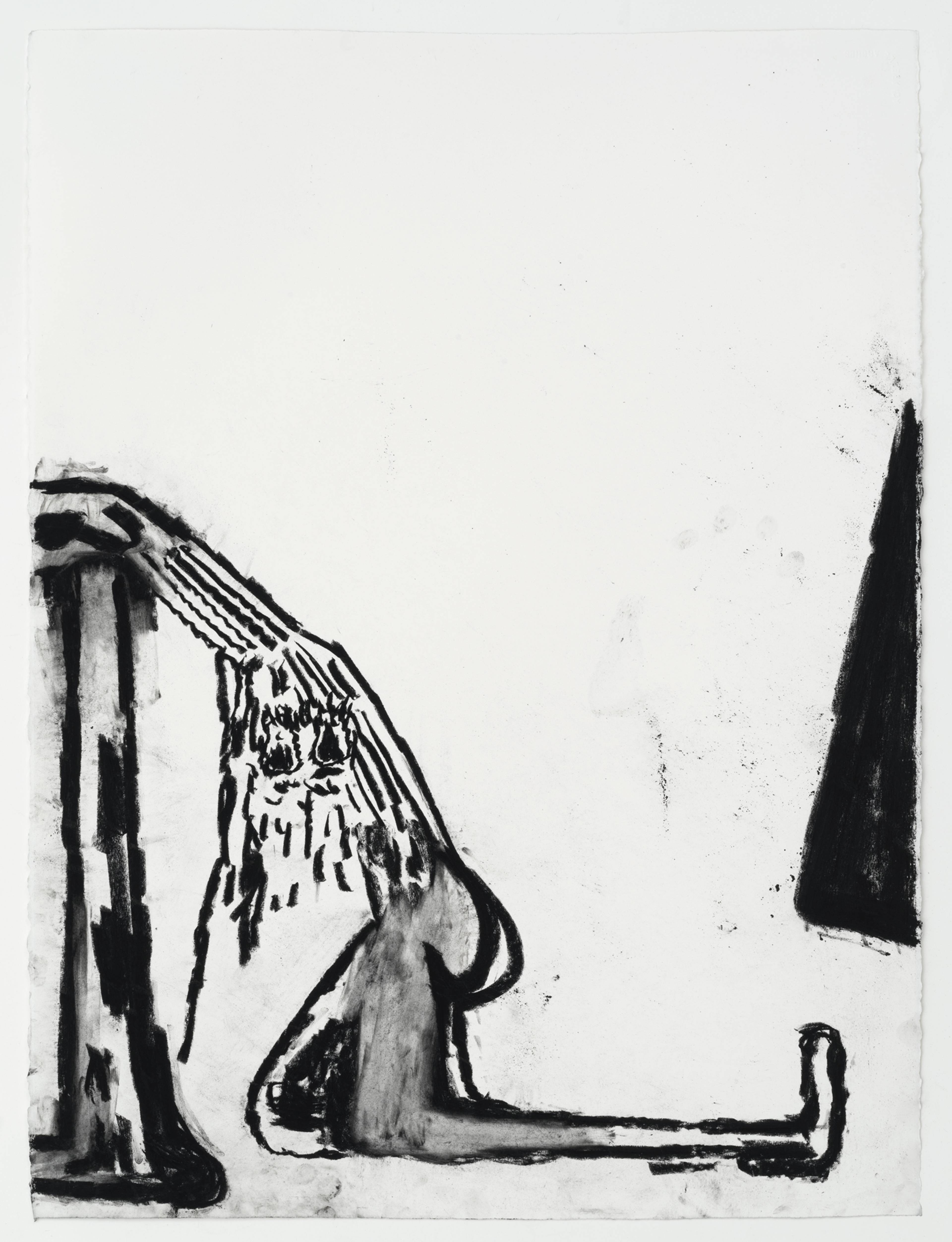

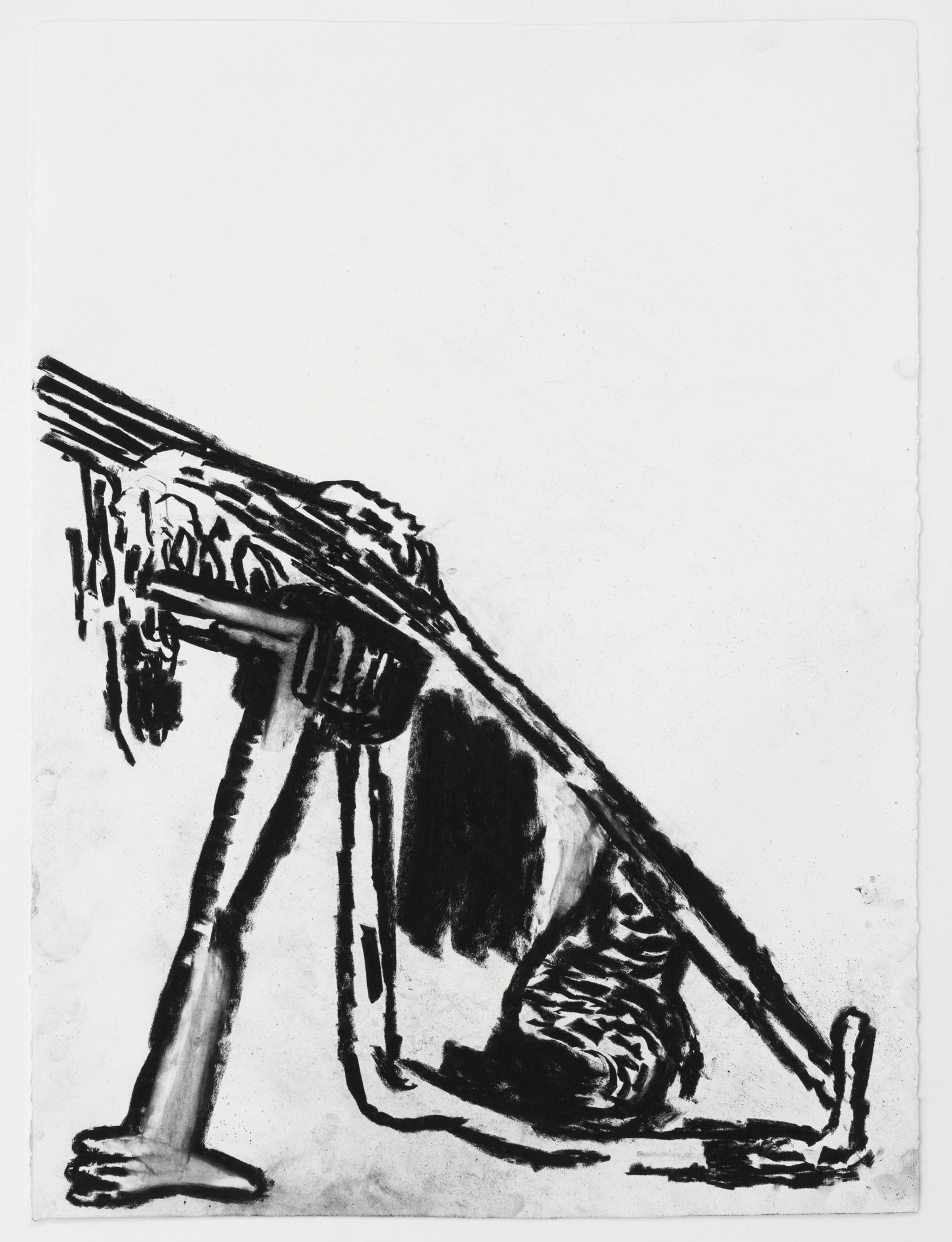

Selections from the series “Election Drawings,” 2016, charcoal on paper, each 76.2 x 58.4 cm

Courtesy: the artist

This is an intermingled one, but there are more complementary ways of experiencing as well, Sillman suggests. Eight of her “Election Drawings” (2016) are displayed in another room: large charcoal works on paper whose recurring character is a stiff, puppetish figure. Rather than possessing an absent or metaphysical character, it is an expressive caricature unnaturally posed, with disjointed limbs and protrusions from random orifices, in various acts of crawling and puking. It is a monstrous representation and, per its title and year, a reflection on contemporary political horrors in the tradition of Goya’s “Caprichos” (Caprices, 1799). The puppet, however, retains its conventional impotence, both ridiculous in the exposure of its grotesque and dismembered body, and titanic in its submission to each drawing’s heavy, empty white upper half. On the room’s remaining three walls, the body takes on more gendered connotations, as Sillman plays with other traditional genres such as portrait and still life; among the glazes, layers, and bold lines, one can discern more feminine characteristics, like wider hips, vaginas, breasts. The explosion of color, overwhelmingly red, pink, and green, in paintings such as Afternoon (2024) or Queenie (2023), brings us back to an organic depiction of the intimate, sexually joyful world, an ideal antiphony to the charcoal traumata of the “Election Drawings.”

Afternoon, 2024, acrylic and oil on linen, 190.5 x 167.6 cm

Queenie, 2023, acrylic and oil on linen, 205.7 x 190.5 cm. Courtesy: the artist

Upstairs, Sillman activates another gateway by displaying three of her works from other collections alongside a selection from the Kunstmuseum Bern’s, re-enabling memory games between and across the works – a cluster of both subtle and overt references (memorably weird are Sophie Tauber-Arp’s gouached shapes “impossibly” cut out with Christian Boltanski’s plasticine scissors) – and between the two floors – a contrast between the relatively full and rhizomatic (above) and the relatively clean and geometric (below). When artists play at being curator, they reveal for sure their own subjective taste, but also a strong-willed inner canon, evidence of their journey into their own partisan and universal art history. It’s as if they were holding a deeper, intuitive mirror up to the primary reflections of their fragmented consciousness, before reconstructing an idea of unity out of the contingencies of preference.

Views of “Oh, Clock!,” Kunstmuseum Bern, 2024. © Kunstmuseum Bern. Photos: Rolf Siegenthaler

In the end, one must concede the proof of the paradox: In this exhibition, we are ultimately looking, not at Sillman’s work per se, but at her processes, which allows for a more intimate and precious access to the artist’s imagery. Sillman, to steal a Susan Sontag formula, has here invited us with “irrepressible eccentricity” into her singular worldview.

___

“Oh, Clock!”

Kunstmuseum Bern

20 Sep 2024 – 2 Feb 2025